ENGLISH LANGUAGE 2

advertisement

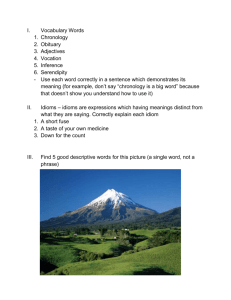

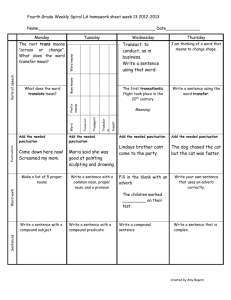

ENGLISH LANGUAGE TWO Dear Students, The purpose of this rather practical course is to try to help you to hone and sharpen your skills in English grammar, syntax, punctuation, vocabulary, idioms, and overall structure. It follows logically from my more theoretical course on ‘History of the English language’. Students will be encouraged to simplify sloppy English, avoid linguistic bulimia, use idioms correctly, and identify different types of English. The course takes the form of lectures and exercises, which can include writing, correcting and improving bad English, ‘mixed sentences tests’, comparing dialects, and even cryptic crossword clues. You will find that most of the exercises create the subliminal effect of thinking in English. Evaluation is by an unseen written examination. Before we start looking at the sort of things that we shall do, consider this, written for me by one of my best former St. Pauls School schoolmasters, John Bayliss: Bayliss’ Law of Punctuation 1. An essay is like a formal meal: it has distinct and different parts; a beginning, (several) middles and an end. The end does not repeat the beginning; rather it provokes a satisfied sigh (rather than a burp!). 2. Similarly, a paragraph is a self-contained course. 3. Within the paragraph-course, the sentence is a mouthful; the full stop says: ‘Swallow this before proceeding.’ Similarly, the comma is a pause in the chewing of a long sentence-mouthful; ‘Take a short break, or hiccups may result.’ 4. The larger sub-stops are designed for a major titbit, to wit the colon and semicolon. 1 5. The colon is a splendidly economical shorthand device. It says: I will explain…’ (It is also used to introduce a quotation.) 6. The semi-colon juxtaposes two halves of a balanced sentence, like the fulcrum of a seesaw: A ; B Δ It replaces a conjunction such as ‘whereas’, ‘and’, ‘yet’ etc. 7. In a multiple explanation, the semi-colon is used to offset equal elements: A: X; Y; Z. (After the initial colon.) Bon appétit! Let us now look at a few idioms, many of which come from sports such as cricket and football. An ‘innings’ is part of a cricket match. If one bats or bowls well in an innings, one therefore has a good innings. If someone has a good innings, then it can also mean that he had a long life. So if you are asked in the examination to explain the meaning of this idiom by using an example, you could write: ‘He died at the age of ninety three: he had a good innings’. Other ‘sporting idioms’ are ‘on a losing wicket’, ‘on a sticky wicket’, ‘bowled over’, ‘on the ball’, and ‘off his own bat.’ You had better start noting down idioms in your reading. Here are a few more: ‘to take French leave’, ‘to go Dutch’, ‘to beat about the bush’, ‘to be in the doldrums’, ‘to give it a miss’, ‘to get down to brass tacks’, ‘off the cuff’, ‘ a long shot’, ‘round the bend’, ‘kick the bucket’, ‘a cut above the rest’, and ‘cloud the issue’. Apart from simple idioms, we shall look at connected and overlapping things such as metaphors, alliteration, allegories, spoonerisms, similes, axioms, maxims, tenets, aphorisms (it is not always easy to distinguish between these last four) and malapropisms. It is up to you to ascertain precisely what all these are, and find examples, but I shall help you a little now: a ‘spoonerism’ is when you transpose, 2 usually accidentally, the first letters of two or more words. An example is: ‘You hissed my mystery lecture’ (should be ‘missed’ and ‘history’). Drunken people sometimes create spoonerisms. The word originates from the Reverend Spooner, who was reputed to have made such errors when speaking. A ‘malapropism’ is when you use a word by mistake, for one sounding similar, for example ‘allegory’ instead of ‘alligator’. Insecure people wishing to impress others with their knowledge sometimes commit malapropisms. It originates from a character, Mrs. Malaprop, from Sheridan’s play ‘The Rivals’. ‘Malapropos’, incidentally, means ‘inopportune(ly)’ or inappropriate(ly)’. A word now about rhyming slang, a form of verbal communication replacing words with rhyming words or phrases. For example, instead of saying ‘stairs’, you say ‘apples and pears’, or, even more cryptically, just ‘apples’. ‘Give us a butcher’s’ means ‘give us a look’, from ‘butcher’s hook’. It is said by some that rhyming slang originated with the Cockneys in London’s East End, when criminals wished to talk to each other in coded language. Now we move on to linguistic bulimia: in recent years, the situation has become abysmal. If you read George Orwell’s celebrated essay ‘Politics and the English Language’, you will understand the cancer that has attacked proper English. Let us quote from his essay: ‘It is easier – even quicker, once you have the habit – to say in my opinion it is a not unjustifiable assumption that than to say I think. […] The great enemy of clear language is insincerity. […] In our age, there is no such thing as “keeping out of politics”. All issues are political issues, and politics itself is a mass of lies, evasions, folly, hatred and schizophrenia.’ The less secure you are, the more likely you are to hide behind meaningless verbosity, jargon, superfluity and the language of PR and propaganda. Take a look at this: ‘Notwithstanding the constant ongoing process of the negotiations with France over oil-drilling rights, it is now necessary to ask the Americans if they could be kind enough to step in and offer their services to arbitrate in our dispute with the French.’ This actually means: ‘Despite our current negotiations with France over oil-drilling rights, we should ask the Americans to arbitrate.’ In this connexion, beware words, phrases and euphemisms like ‘window of opportunity’(opportunity), ‘in the 3 intervening period’ (meanwhile), ‘collateral damage’(manslaughter), ‘targeted killing’(assassination), ‘period of time’(period), ‘corporate downsizing’ (sacking staff), ‘intimate apparel’ (underwear),’physically challenged’ (assaulted), ‘in my humble opinion’ (in my self-satisfied opinion), ‘owing to the fact that’ (because) and ‘ongoing’ (continuing). Apart from linguistic bulimia, muddled language betrays muddled thinking, so your first step is to seek clarity and simplicity, and then to learn how to transform your hopefully clearer thinking into words. Many propaganda experts use linguistic bulimia expressly, simply to pull the wool over your eyes. This can have the unfortunate effect of affecting your own language adversely. We now move on to ‘mixed sentences’. Again, you can only solve them by thinking in English. You have to underline the two words of a sentence that I have deliberately misplaced. For example: ‘He admires the whatever thing, right the right thing is, and one of these days, he is going to write a great work.’ As regards punctuation skills, try the following, where you must insert the correct punctuation among the words, so that they make sense (you may use capital letters where necessary): ‘That that is is that that is not is not is not that it it is.’ A possible solution is: ‘That that is, is. That that is not, is not. Is not that it? It is!’ And now, what about the meaning of meaning? The following sentence has more than one meaning. Try to write out precise meanings only by altering the order of the words and/or by inserting punctuation: ‘We discussed the problem of female students’ liaisons with male lecturers in the boardroom’. Some solutions would be: a) In the boardroom, we discussed the problem of female students’ liaisons with male lecturers. b) In the boardroom, we discussed with male lecturers the problem of female students’ liaisons. c) We discussed with male lecturers the problem of female students’ liaisons in the boardroom. 4 On this course, we also touch on different Englishes, and the differences between, for example Scottish English and English, and American English and English. In Scotland ‘bonny’, which comes from ‘the auld alliance’ with France, means ‘pretty’, ‘wee’ means ‘tiny’, and a ‘burn’ is a ‘stream’. In the USA, ‘apartment’ means ‘flat’, ‘chips’ mean ‘crisps’, ‘French’ (or ‘Freedom’!) fries’ means ‘chips’, ‘vacation’ means ‘holiday(s)’, and ‘movie’ means ‘film’. If an Englishman mentions the word ‘rubber’ in the US, people will think that he is talking about a prophylactic, when he only means an ‘eraser’. In Britain you can say that you will ‘knock someone up’ (visit him or her), while in the US, it means to perform sexual intercourse with someone. So watch your step! And now an exercise to encourage you to think about synonyms (or near synonyms). Consider the following two words, and then find a third word close in meaning to the first one, which is similar in rhyme and/or rhythm to the second: struggle, night = fight; believable, edible = credible; meander, bramble = ramble; inconspicuous, congealed = concealed. You can even make up your own exercises. Finally, let us turn to cryptic crossword clues, an interesting way of considering the way in which many English people think. Here is a clue: ‘Big discovery when tunnellers reach their destination’ (12) = breakthrough. Why? Because when you are tunnelling underground, you break through at the end, and because a ‘breakthrough’ can be a kind of discovery. Apart from this way of thinking, many cryptic clues are based on anagrams: Pester and disturb e.g. Paul (6) = plague. ‘Pester’ is connected to ‘pest’, such as a rat, which can cause disease, and the letters ‘e.g. Paul’ are disturbed (put into a different order), to give us the answer. And here’s another one: ‘Cheese, some sun-drenched Darjeeling and…’ (7) = Cheddar. This is because the clue is in two words; ‘drenched Darjeeling’. In many ways, one needs to think very literally to solve such clues, yet at the same time it is arguable that there is an element of subtlety. Is this an indication of the English mind, or am I stretching credibility? A final thought: one day, many of you will be confronted with translating and/or interpreting bad English. You will need to know the speakers, writers and audiences to be able to judge whether to translate and/or interpret into bad Greek, or not. What a 5 professional conundrum! Should a speaker or writer of bad and bulimic English be protected? That’s it for now. Good luck with your studies. Am I a word merchant who pays for my misdemeanours in syntax? Yours, William Mallinson Dr.William Mallinson, 18 March 2012 in the year of our Lord. 6