Obeying the Law

advertisement

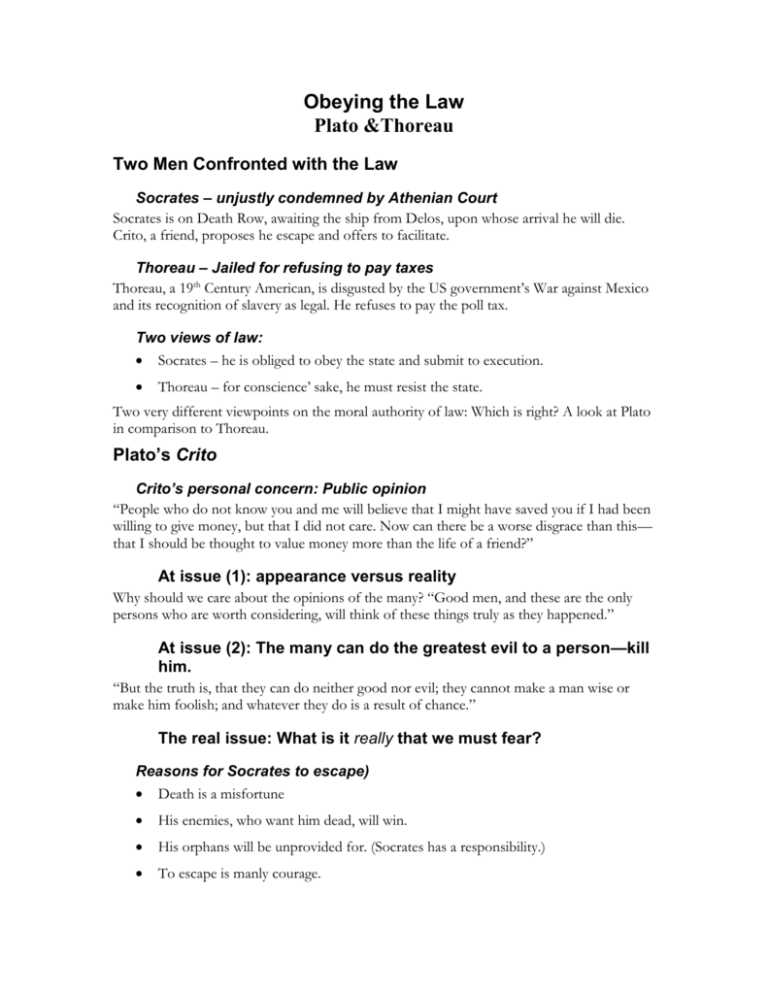

Obeying the Law Plato &Thoreau Two Men Confronted with the Law Socrates – unjustly condemned by Athenian Court Socrates is on Death Row, awaiting the ship from Delos, upon whose arrival he will die. Crito, a friend, proposes he escape and offers to facilitate. Thoreau – Jailed for refusing to pay taxes Thoreau, a 19th Century American, is disgusted by the US government’s War against Mexico and its recognition of slavery as legal. He refuses to pay the poll tax. Two views of law: Socrates – he is obliged to obey the state and submit to execution. Thoreau – for conscience’ sake, he must resist the state. Two very different viewpoints on the moral authority of law: Which is right? A look at Plato in comparison to Thoreau. Plato’s Crito Crito’s personal concern: Public opinion “People who do not know you and me will believe that I might have saved you if I had been willing to give money, but that I did not care. Now can there be a worse disgrace than this— that I should be thought to value money more than the life of a friend?” At issue (1): appearance versus reality Why should we care about the opinions of the many? “Good men, and these are the only persons who are worth considering, will think of these things truly as they happened.” At issue (2): The many can do the greatest evil to a person—kill him. “But the truth is, that they can do neither good nor evil; they cannot make a man wise or make him foolish; and whatever they do is a result of chance.” The real issue: What is it really that we must fear? Reasons for Socrates to escape) Death is a misfortune His enemies, who want him dead, will win. His orphans will be unprovided for. (Socrates has a responsibility.) To escape is manly courage. Socrates’ response: To follow the path he has always taken First, whose advice should he take? Some say, “Take our advice. Flee! Escape from prison.” Compare: Whose advice should the athlete take? The fans’ advice or his trainer’s? Or the sick man – his doctor’s or someone else’s? We are talking about the faculty that justice improves and injustice damages Socrates is talking about what makes one good as a human being, not just good in some respect (e.g. health or athletics). This is more important than the body. It is not just life, but a good life that is to be valued. So the decision depends on what is right and not on what will save Socrates’ life. “In questions of just and unjust, fair and foul, good and evil, which are the subjects of our present consultation, ought we to follow the opinion of the many and to fear them; or the opinion of the one man who has understanding, and whom we ought to fear and reverence more than all the rest of the world… and whom deserting we shall destroy and injure that principle in us which may be assumed to be improved by justice and deteriorated by injustice—is there not such a principle?” First things first: A good life “And will life be worth having, if that higher part of man be depraved, which is improved by justice and deteriorated by injustice?” Trust in argument. Do justice, whether easy or not: “we are never intentionally to do wrong.” “Then we ought not to retaliate or render evil for evil to anyone, whatever evil we may have suffered from him.” Most people don’t agree with this, but is it true? The Challenge: Is it right to do evil to avoid evil? “Tell me then, whether you agree with and assent to my first principle, that neither injury nor retaliation nor warding off evil by evil is ever right.” (51) Socrates’ imaginary dialogue with the Laws Moral principle: Is it right to harm an undeserving victim, without his permission? Disobeying the laws will destroy the state. How? “Do you imagine that a state can subsist and not be overthrown, in which the decisions of law have no power, but are set aside and overthrown by individuals?”) The State’s decision was unjust. But is that to the point? The agreement was that Socrates would obey the laws. He who disobeys is wrong three ways: 1. He also disobeys his parents. 2. State is author of his education. “Well then, since you were brought into the world and nurtured and educated by us, can you deny in the first place that you are our child and slave, as your fathers were before you? And if this is true you are not on equal terms with us; nor can you think that you have a right to do to us what we are doing to you. […] Has a philosopher like you failed to discover that our country is more to be valued and higher and holier far than mother or father or any ancestor, and more to be regarded in the eyes of gods and men of understanding?” 3. He has made an agreement to obey our commands. Socrates’ compliance was not demanded; he had the chance to obey or persuade. At his trial S. could have elected exile. (Consider this: even today we accept the court’s judgment even when it goes against us.) Socrates was free to leave when he came of age. By staying he entered into an implied contract with the state. As long as you live here, you accept this society and this government. This idea appears later in John Locke and the social contract theory of the state. If he leaves: “You, Socrates, are breaking the covenants and agreements which you made with us at your leisure, not in any haste or under any compulsion or deception, but having had seventy years to think of them, during which you were at liberty to leave the city, if we were not to your mind, or if our covenants appeared to you to be unfair.” Only the just life is worth living (54) Without his integrity, Socrates will be a “flatterer and slave of all”. He will be alive, but no longer any good. “Think not of life and children first and of justice afterwards, but of justice first. […] Now you depart in innocence, a sufferer and not a doer of evil; a victim, not of the laws, but of men.” (55) Thoreau’s “On the Duty of Civil Obedience” Government as a necessary evil “That government is best which governs least.” Government is an expedient; we should even reconsider whether we need a standing government. Government does not accomplish anything. The people do all the good things – and they would do more – were it not for government. Even democracy is not all that great. Majority is not right nor is majority rule particularly fair, but the majority is strongest. The primacy of personal conscience “Must every citizen ever for a moment, or in the least degree, resign his conscience to the legislator? … I think that we should be men first, and subjects afterward.” “Law never made men a whit more just; and by means of their respect for it, even the well-disposed are made the agents of injustice.” Cogs in the wheel of state “The mass of men serve the state thus, not as men mainly, but as machines, with their bodies.” Two specific evils Slavery in the US “I cannot for an instant recognize that political organization as my government which is the slave’s government also.” The American revolutionaries objected to the British taxes on tea and the Stamp Act. But one-sixth of the population are slaves. Mexican War The United States has unjustly invaded another country. Complacency and inaction before evil are complicity. Simply voting is not enough. To vote is not to act. Obligations of conscience First, it is not everyone’s duty to eradicate every evil, but It is a duty to wash one’s hands of it – not to contribute to it. For example, everyone pays taxes. “If the injustice is part of the necessary friction of the machine of government, let it go, let it go: perchance it will wear smooth – certainly the machine will wear out…but if it is of such a nature that it requires you to be the agent of injustice to another, then, I say, break the law. Let your life be a counter-friction to stop the machine.” Even to jail? “Under a government which imprisons any unjustly, the true place for a just man is also a prison.” Is this true? Compare with Socrates Like Socrates, Thoreau says that he should not do evil. But he uses this to say he should not obey the state, because what the state is doing is evil. Our Country as our Parents? “We must affect our country as our parents,/ And if at any time we alienate/ Our love of industry from doing it honor,/ We must respect effects and teach the soul/ Matter of conscience and religion,/ and not desire rule or benefit.” But does this apply to government? Notice the faint praise for the US Constitution and system of government. The authority of government Government authority is impure. “To be strictly just, it must have the sanction and consent of the governed. (Cf. Declaration of Independence) It can have no pure right over my person and property but what I concede to it.” The individual is higher than the state. “There will never be a really free and enlightened State until the State comes to recognize the individual as a higher and independent power, from which all its own power and authority are derived, and treats him accordingly.” Some questions these readings raise 1. Is the citizen always obliged to obey the law? Note that Socrates disobeyed the command of the Thirty when ordered to arrest Leon the Salaminian. (Apology) Instead, he just walked home. 1.1. Under what conditions is it morally OK to break the law? 1.2. Can a law itself ever be unjust? 2. Is civil disobedience – such as Thoreau’s refusing to pay taxes – ever justified? 2.1. Some examples: Gandhi’s walk to the sea and attempts to enter salt mines; civil rights sit-ins in the American South; Vietnam War resisters’ moving to Canada. 3. Is Socrates right about how much he owes the state? – basically his entire life? That is, what do we owe the community we were born into and live in? 4. Is Thoreau right about the superiority of the individual over the state? 5. What is conscience? Is it ever higher than civil law? If so, when and why (or why not)?