BRITISH PRIME MINISTERS OF THE 19TH CENTURY NOTE

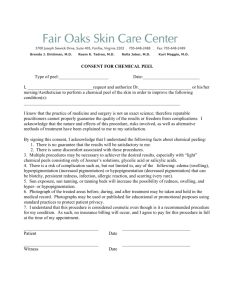

advertisement

BRITISH PRIME MINISTERS OF THE 19TH CENTURY SIR ROBERT PEEL Robert Peel was born in Bury, Lancashire, on 5th February, 1788. His father, Sir Robert Peel (1750-1830), was a wealthy cotton manufacturer and Member of Parliament for Tamworth. Robert was trained as a child to become a future politician. Every Sunday evening he had to repeat the two church sermons that he had heard that day. Robert Peel was educated at Harrow School and Christ Church, Oxford, where he won a double first in classics and mathematics. In 1809 Sir Robert Peel rewarded his son academic success by buying him the parliamentary seat of Cashel in Tipperary (exchanged for Chippenham in 1812). Robert Peel entered the House of Commons in April 1809, at the age of twenty-one. Like his father, Robert Peel supported the Duke of Portland's Tory government. He made an immediate impact and Charles Abbott, the Speaker of the House of Commons, described Peel's first contribution to a debate as the "the best first speech since that of William Pitt." After only a year in the House of Commons the Duke of Portland offered him the post of undersecretary of war and the colonies. Working under Lord Liverpool, Peel helped to direct the military operations against the French. When Lord Liverpool became prime minister in May 1812, Peel was appointed as chief secretary for Ireland. In his new post Peel attempted to bring an end to corruption in Irish government. He tried to stop the practice of selling public offices and the dismissal of civil servants for their political views. At first Peel also attempted to end those aspects of government that gave preference to Protestants over Catholics. However, Robert Peel was not successful in carrying out this policy and eventually he became seen as one of the leading opponents to Catholic Emancipation. In 1814 he decided to suppress the Catholic Board, an organisation started by Daniel O'Connell. This was the start of a long conflict between the two men. In 1815 Peel challenged O'Connell to a duel. Peel traveled to Ostend but O'Connell was arrested on the way to fight the duel. In 1817 Robert Peel decided to retire from his post in Ireland. This upset the Irish Protestants in the House of Commons and fifty-seven of them signed a petition urging him not to leave a post that they believed he had "administered with masterly ability". Oxford University acknowledged Peel's "services to Protestantism" by inviting him to become its member of the House of Commons. In 1822 Peel rejoined Lord Liverpool's government when he accepted the post of Home Secretary. Over the next five years Peel was responsible for large-scale reform in the legal system. This involved repealing over 250 old statutes. Lord Liverpool was struck down by paralysis in February 1827 and was replaced by George Canning as prime minister. Canning was an advocate of Catholic Emancipation and as Peel was strongly opposed to this, he felt he could not serve under the new prime minister and resigned from office. After the death of Canning, Peel returned to government as Home Secretary in the government led by the Duke of Wellington. On 26th July, 1828, Lord Anglesey, wrote to Peel arguing that Ireland was on the verge of rebellion and asked him to use his influence to gain concessions for the Catholics. Although Peel had opposed Catholic Emancipation for twenty years, Lord Anglesey's letter encouraged him to reconsider his position. Peel now wrote to Wellington saying that "though emancipation was a great danger, civil strife was a greater danger". He also added that as William Pitt had rightly said: "to maintain a consistent attitude amid changed circumstances is to be a slave of the most idle vanity". Although the Duke of Wellington agreed with Peel, King George III was violently opposed to Catholic Emancipation. When Wellington's government threatened to resign the king reluctantly agreed to a change in the law. When Peel introduced the Catholic Emancipation Act on 5th March, 1829, he told the House of Commons that the credit for the measure belonged to his long-time opponents, Charles Fox and George Canning. For a long time politicians had been concerned about the problems of law and order in London. In 1829 Robert Peel decided to reorganize the way London was policed. As a result of this reform, the new metropolitan police force became known as "Peelers" or "Bobbies". In November 1830, Wellington's government was replaced by a new administration headed by Earl Grey. For the first time in over twenty years in the House of Commons, Peel was now a member of the opposition. Peel was totally against Grey's proposals for parliamentary reform. Between 12th and 27th July 1831, Peel made forty-eight speeches in the House of Commons against this measure. One of Peel's main arguments was that the system of rotten boroughs had enabled distinguished men to enter parliament. After the passing of the 1832 Reform Act the Tories were heavily defeated in the general election that followed. Although victorious at Tamworth, Peel, now leader of the Tories, only had just over hundred MPs he could rely on to support him against Earl Grey's government. In November 1834 King William IV dismissed the Whig government and appointed Robert Peel as his new prime minister. Peel immediately called a general election and during the campaign issued what became known as the Tamworth Manifesto. In his election address to his constituents in Tamworth, Peel pledged his acceptance of the 1832 Reform Act and argued for a policy of moderate reforms while preserving Britain's important traditions. The Tamworth Manifesto marked the shift from the old, repressive Toryism to a new, more enlightened Conservatism. The general election gave Peel more supporters although there were still more Whigs than Tories in the House of Commons. Despite this, the king invited Peel to form a new administration. With the support of the Whigs, Peel's government was able to pass the Dissenters' Marriage Bill and the English Tithe Bill. However, Peel was constantly being outvoted in the House of Commons and on 8th April 1835 he resigned from office. In August 1841 Robert Peel was once again invited to form a Conservative administration. Over the last few years Britain had been spending more than it was earning. Peel decided the government had to increase revenue. On 11th March, 1842, he announced the introduction of income-tax at seven pence in the pound. He added that he hoped that this was enabling the government to reduce duties on imported goods. In 1843 Peel once more had problems with Daniel O'Connell, who was leading the campaign against the Act of Union. O'Connell announced a large meeting to be held at Clontarf. The British government pronounced it illegal and when O'Connell continued to go ahead with his planned Clontarf meeting he was arrested and imprisoned for conspiracy. Peel attempted to overcome the religious conflict in Ireland by setting up the Devon Commission to inquire into the "state of the law and practice in respect to the occupation of land in Ireland." He also increased the grant to Maynooth, a college for the education of the Irish priesthood, from £9,000 to £26,000 a year. However, Peel's attempts to improve the situation in Ireland were severely damaged by the 1845 potato blight. The Irish crop failed, therefore depriving the people of their staple food. Peel was informed that three million poor people in Ireland who had previously lived on potatoes would require cheap imported corn. Peel realised that they only way to avert starvation was to remove the duties on imported corn. Although the Corn Laws were repealed in 1846, the policy split the Conservative Party and Peel was forced to resign. Robert Peel continued to attend the House of Commons and gave considerable support to Lord John Russell and his administration in 1846-47. On 28th June 1850 he gave an important speech on Greece and the foreign policy of Lord Palmerston. The following day, while riding up Constitution Hill, he was thrown from his horse. Peel was badly hurt and on 2nd July, 1850, he died from his injuries. LORD PALMERSTON Henry John Temple, son of the Irish peer, Viscount Palmerston, was born at Broadlands, Hampshire, on 29th October, 1784. Educated at Harrow School and St. John's College, Cambridge, he succeeded to the Irish peerage on his father's death on 16th April 1802. At the age of twenty-two Palmerston, a Tory, paid £1,500 to become the MP for Horsham. The legality of the election was challenged and the following year Sir Leonard Holmes, arranged for Palmerston to become MP for his pocket borough of Newtown on the Isle of Wight (in 1811 he became MP for Cambridge University). One of the conditions set by Holmes was that Palmerston was not allowed, even during election campaigns, to visit Newtown. Later that year, Palmerston's guardian, Lord Malmesbury, arranged for him to become appointed as lord of the admiralty in the Duke of Portland's administration. In October 1809, the new Prime Minister, Spencer Perceval, offered Palmerston the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. As he was only twenty-five years old, Palmerston thought he was too young for this high office and instead accepted the post of Secretary at War. Lord Palmerston held this post for twenty years serving five Prime Ministers, Lord Liverpool, George Canning, Lord Goderich and the Duke of Wellington. Although he had always been a member of Tory administrations, Lord Palmerston accepted the offer to join Lord Grey and his Whig government in 1830. Palmerston became Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, and for the next two years was preoccupied with persuading France and Holland to accept that independence of Belgium. One of the conditions of being a member of Lord Grey's government was to support the Whig policy of parliamentary reform. Although Palmerston had previously been opposed to parliamentary reform, he agreed to support Grey's proposed measures. The decision upset his electors at Cambridge University and he was forced to move to Bletchley and when this seat disappeared as a result of the 1832 Reform Act he became the MP for South Hampshire. Between 1832 and 1852 Lord Palmerston served both Whig (Lord Melbourne, Lord John Russell) and Tory (Sir Robert Peel) governments. Although Palmerston had the support of most of Parliament, he was strongly disliked by Queen Victoria. Palmerston believed the main objective of the government's foreign policy should be to increase Britain's power in the world. This sometimes involved adopting policies that embarrassed and weakened foreign governments. Victoria and her husband, Prince Albert, on the other hand, believed that the British government should do what it could to help preserve European royal families against revolutionary groups advocating republicanism. This was very important to Victoria and Albert as they were closely related to several of the European royal families that faced the danger of being overthrown. Victoria also objected to Palmerston's sexual behaviour. On one occasion he had attempted to seduce one of Victoria's ladies in waiting. Palmerston entered Lady Dacre's bedroom while staying as Victoria's guest at Windsor Castle. Only Lord Melbourne's intervention saved Palmerston from being removed from office. In the summer of 1850, Queen Victoria asked Lord John Russell to dismiss Palmerston. Russell told the queen he was unable to do this because Palmerston was very popular in the House of Commons. However, in December 1851, Palmerston congratulated Louis Napoleon Bonaparte on his coup in France. This action upset Russell and other radical members of the Whig party and this time he accepted Victoria's advice and sacked Palmerston. Six weeks later Palmerston took revenge by helping to bring down Lord John Russell's government. In 1855 Lord Palmerston, aged seventy, became Prime Minister. Queen Victoria found it difficult to work with him but their relationship gradually improved. She later wrote in her journal: "We had, God knows! terrible trouble with him about Foreign Affairs. Still, as Prime Minister he managed affairs at home well, and behaved to me well. But I never liked him." Palmerston first period as Prime Minister lasted for three years. His second period started in 1859 when he was seventy-five years old. The main foreign events that he had to deal with during this period included the American Civil War and Napoleon III's war with Austria. The main domestic issue involved the continuing debate over parliamentary reform. Palmerston was totally opposed to any extension of the franchise and during 1864 came into conflict with William Gladstone, his Chancellor of the Exchequer, who was a strong supporter of reform. Palmerston won the argument and Gladstone had to wait until he became Prime Minister before he could introduce these measures. Parliament was dissolved on 6th July 1865. Although nearly eighty-one years old, Palmerston refused to retire and once again was elected to Parliament. However, before he could take up office he became very ill and was forced to stay at his estate at Brocket Hall, Hertfordshire. Lord Palmerston died on 18th October, 1865. SIR WILLIAM GLADSTONE William Ewart Gladstone, the fourth son of Sir John Gladstone, was born in Liverpool on 29th December, 1809. Gladstone was a MP and a successful Liverpool merchant. William was educated at Eton and Christ College, Oxford. At the Oxford Union Debating Society Gladstone developed a reputation as a fine orator. At university Gladstone was a Tory and denounced Whig proposals for parliamentary reform. In 1832, the Duke of Newcastle was looking for a Conservative candidate for his Newark constituency. Although a nomination borough, Newark had been spared in the 1832 Reform Act. Sir John Gladstone was a friend of the Duke of Newcastle and suggested his son would make a good MP. Two years after entering the House of Commons as MP for Newark, Sir Robert Peel, the Prime Minister, appointed William Gladstone as his junior lord of the Treasury. The following year he was promoted to under-secretary for the colonies. Gladstone lost office when Peel resigned in 1835 but returned to the government when the Whigs were forced out of power in August, 1841. Gladstone now became vice-president of the board of trade and in 1843 was promoted to the post of president. In 1844 Gladstone was responsible for the Railway Bill that introduced what became known as parliamentary trains. As a result of this legislation railway companies had to transport third-class travellers for fares that did not exceed a penny a mile. These parliamentary trains had to stop at every station and had to travel at not less than 12 miles an hour. In 1845 the Duke of Newcastle refused to support Gladstone candidature for Newark. Newcastle was a protectionist and had been upset by Gladstone's conversion to the reform of the Corn Laws. Although no longer an MP, Gladstone remained in Peel's cabinet until the Whig, Lord John Russell became Prime Minister in July 1847. In the 1847 General Election that followed, Gladstone was elected the Conservative MP for Oxford University. He remained on the opposition benches until Lord Aberdeen formed a coalition government with Lord Palmerston as Home Secretary, Lord John Russell as Foreign Secretary and Gladstone as Chancellor of the Exchequer. Aberdeen's government survived until March 1857. When Lord Palmerston, the leader of the Whigs, became Prime Minister in June, 1859, he offered Gladstone the post of Chancellor of the Exchequer. One of his most important reforms was the abolition of the paper duty which enabled publishers to produce cheap newspapers. Gladstone had always opposed parliamentary reform but when Edward Baines introduced a reform bill he spoke in favour of the measure. In his speech Gladstone pointed out that only one fiftieth of the working classes had the vote. He argued that this was unfair and that the law should be changed to increase this number. However, this was very much a minority view and Baines' proposal was defeated by 272 votes to 56. In the general election of July 1865, the voters at Oxford University had been upset by Gladstone's move from the Conservative Party and he lost his seat. Gladstone now moved to South Lancashire. Lord John Russell, the new Prime Minister, asked Gladstone to become leader of the House of Commons as well as Chancellor of the Exchequer. On 12th March 1866, Gladstone introduced the government's new reform bill. In the debate Gladstone admitted that he was a recent convert to parliamentary reform. With Conservative opposition to the measure, Russell's government found it impossible to get the bill passed by the House of Commons. On 19th June 1866, Russell's administration resigned. Lord Derby, leader of the Conservatives, now became Prime Minister. The Conservatives knew that if the Liberals returned to power, Russell and Gladstone were certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli, leader of the House of Commons, argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later Marquis of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. In the general election of December 1868, the Conservatives were defeated and Gladstone, leader of the Liberal Party, became Prime Minister. In 1870 Gladstone and his education minister, William Forster, managed to persuade Parliament to pass the government's Education Act that established school boards in Britain. After the passing of the 1867 Reform Act working class males now formed the majority in most borough constituencies. However, employers were still able to use their influence in some constituencies because of the open system of voting. In parliamentary elections people still had to mount a platform and announce their choice of candidate to the officer who then recorded it in the poll book. Employers and local landlords therefore knew how people voted and could punish them if they did not support their preferred candidate. In 1872 Gladstone's removed this intimidation when his government brought in the Ballot Act which introduced a secret system of voting. In the 1874 general election the Conservative majority was forty-six. Benjamin Disraeli became Prime Minister and Gladstone led the opposition. For the next couple of years Gladstone concentrated on writing his book An Inquiry into the Time and Place of Homer in History (1876). However, he was stirred into action when he read about the massacres and tortures inflicted upon the inhabitants of Bulgaria by their Turkish rulers. This resulted in him writing a pamphlet Bulgarian Horrors and the Question of the East (1876). Parliament was dissolved in 1880, and the general election resulted in an overwhelming Liberal victory. Gladstone now introduced three new measures concerning parliamentary reform. The Corrupt Practices Act specified how much money candidates could spend during election time and banned such activities as the buying of food or drink for voters. The act even stated the number of conveyances that could be used for bringing voters to the polls. In 1884 Gladstone introduced his proposals that would give working class males the same voting rights as those living in the boroughs. Although the bill was passed in the House of Commons it was rejected by the Conservative dominated House of Lords. Gladstone refused to accept defeat and reintroduced the measure. This time the Conservative members of the Lords agreed to pass Gladstone's proposals in return for the promise that it would be followed by a Redistribution Bill. Gladstone accepted their terms and the 1884 Reform Act was allowed to become law. This measure gave the counties the same franchise as the boroughs - adult male householders and £10 lodgers - and added about six million to the total number who could vote in parliamentary elections. Gladstone and the Liberal Party won the 1886 general election. Gladstone now attempted to convince Parliament to accept Irish Home Rule. The proposal split the party and Parliament rejected the measure. Gladstone was defeated in the polls in the 1886 General Election but was once again elected to office in 1892. The following year the Irish Home Rule Bill was passed in the House of Commons but was defeated in the House of Lords. William Gladstone resigned from office in March 1894 and died at Hawarden on 19th May, 1898. SIR BENJAMIN DISRAELI Benjamin Disraeli was born in London on 21st December, 1804. His father, Isaac Disraeli, was the author of several books on literature and history, including The Life and Reign of Charles I (1828). After a private education Disraeli was trained as a solicitor. Like his father, Isaac Disraeli, Benjamin took a keen interest in literature. His first novel, Vivian Grey was published in 1826. The book sold very well and was followed by The Young Duke (1831), Contarini Fleming (1832), Alroy (1833), Henrietta Temple (1837) and Venetia (1837). Disraeli was also interested in politics. In the early 1830s he stood in several elections as a Whig, Radical and as an Independent. Disraeli's early attempts ended in failure, but he was eventually elected to represent Maidstone in 1837. Disraeli's maiden speech in the House of Commons was poorly received and after enduring a great deal of barracking ended with the words: "though I sit down now, the time will come when you will hear me." Disraeli was now a progressive Tory and advocated triennial parliaments and the secret ballot. He was sympathetic to the demands of the Chartists and in one speech argued that the "rights of labour were as sacred as the rights of property". In 1839 Benjamin Disraeli married the extremely wealthy widow, Mrs. Wyndham Lewis. The marriage was a great success. On one occasion Disraeli remarked that he had married for money, and his wife replied, "Ah! But if you had to do it again, you would do it for love." After the Conservative victory in the 1841 General Election, Disraeli suggested to Sir Robert Peel, the new Prime Minister, that he would make a good government minister. Peel disagreed and Disraeli had to remain on the backbenches. Disraeli was hurt by Peel's rejection and over the next few years he became a harsh critic of the Conservative government. In 1842 Disraeli helped to form the Young England group. Disraeli and members of his group argued that the middle class now had too much political power and advocated an alliance between the aristocracy and the working class. Disraeli suggested that the aristocracy should use their power to help protect the poor. This political philosophy was expressed in Disraeli's novels Coningsby (1844), Sybil (1845) and Tancred (1847). In these books the leading characters show concern about poverty and the injustice of the parliamentary system. Disraeli favoured a policy of protectionism and strongly opposed Peel's decision to repeal the Corn Laws. This issue split the Conservative Party and Disraeli's attacks on Peel helped to bring about his political downfall. In 1852 Lord John Russell, the leader of the Whig government, resigned. Lord Derby, the new Prime Minister, appointed Disraeli as his Chancellor of the Exchequer. This period of power only lasted a few months and Derby was soon replaced by the Earl of Aberdeen. Lord Derby became Prime Minister again in 1858 and once again Disraeli was appointed as Chancellor of the Exchequer. He also became leader of the House of Commons and was responsible for the introduction of measures to reform parliament. In February, 1858, Disraeli proposed the equalization of the town and county franchise. This would have resulted in some men in towns losing the vote and was opposed by the Liberals. An amendment proposed by Lord John Russell "condemning this disfranchisement" was passed by 330 to 291. In 1859 Lord Palmerston, became Prime Minister, and Disraeli once more lost his position in the government. For the next seven years the Liberals were in power and it was not until 1866 that Disraeli returned to the cabinet. Once again, Lord Derby appointed Disraeli as his Chancellor of the Exchequer and leader of the House of Commons. Some members of the Liberal Party, including the new leader, William Gladstone, had been in favour of legislation that would have extended the franchise. His attempts to obtain parliamentary reform failed but Disraeli was convinced that if the Liberals returned to power, Gladstone was certain to try again. Benjamin Disraeli argued that the Conservatives were in danger of being seen as an anti-reform party. In 1867 Disraeli proposed a new Reform Act. Lord Cranborne (later the Marquis of Salisbury) resigned in protest against this extension of democracy. In the House of Commons, Disraeli's proposals were supported by Gladstone and his followers and the measure was passed. The 1867 Reform Act gave the vote to every male adult householder living in a borough constituency. Male lodgers paying £10 for unfurnished rooms were also granted the vote. This gave the vote to about 1,500,000 men. The Reform Act also dealt with constituencies and boroughs with less than 10,000 inhabitants lost one of their MPs. The forty-five seats left available were distributed by: (i) giving fifteen to towns which had never had an MP; (ii) giving one extra seat to some larger towns - Liverpool, Manchester, Birmingham and Leeds; (iii) creating a seat for the University of London; (iv) giving twenty-five seats to counties whose population had increased since 1832. In 1868 Lord Derby resigned and Benjamin Disraeli became the new Prime Minister. However, in the 1868 General Election that followed, William Gladstone and the Liberals were returned to power with a majority of 170. After six years in opposition, Disraeli and the Conservative Party won the 1874 General Election. It was the first time since 1841 that the Tories in the House of Commons had a clear majority. Disraeli now had the opportunity to develop the ideas that he had expressed when he was leader of the Young England group in the 1840s. Social reforms passed by the Disraeli government included: the Artisans Dwellings Act (1875), the Public Health Act (1875), the Pure Food and Drugs Act (1875), the Climbing Boys Act (1875), the Education Act (1876). Disraeli also introduced measures to protect workers such as the 1874 Factory Act and the Climbing Boys Act (1875). Disraeli also kept his promise to improve the legal position of trade unions. The Conspiracy and Protection of Property Act (1875) allowed peaceful picketing and the Employers and Workmen Act (1878) enabled workers to sue employers in the civil courts if they broke legally agreed contracts. Unlike William Gladstone, Disraeli got on very well with Queen Victoria. She approved of Disraeli's imperialist views and his desire to make Britain the most powerful nation in the world. In 1876 Victoria agreed to his suggestion that she should accept the title of Empress of India. In August 1876 Queen Victoria granted Disraeli the title Lord Beaconsfield. Disraeli now left the House of Commons but continued as Prime Minister and now used the House of Lords to explain his government's policies. At the Congress of Berlin in 1878 Disraeli gained great acclaim for his success in limiting Russia's power in the Balkans. The Liberals defeated the Conservatives in the 1880 General Election and after William Gladstone became Prime Minister, Disraeli decided to retire from politics. Disraeli hoped to spend his retirement writing novels but soon after the publication of Endymion (1880) he became very ill. Benjamin Disraeli died on 19th April, 1881.