Disability Discrimination

advertisement

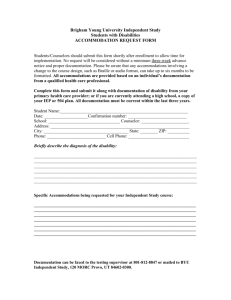

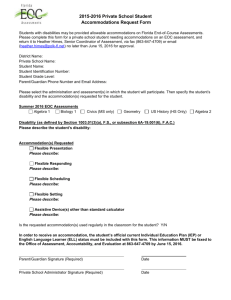

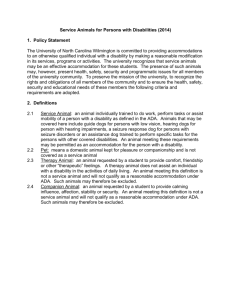

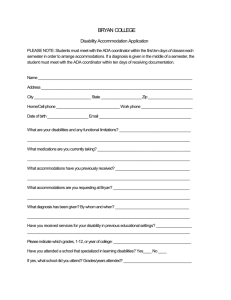

Current Legal Issues for Law School Administrators Disability Discrimination Peter H. Ruger General Counsel Southern Illinois University Carbondale, Illinois Stetson University College of Law: 22nd ANNUAL LAW & HIGHER EDUCATION CONFERENCE Clearwater Beach, Florida February 18-20, 2001 Disability Discrimination I. Major Enactments A. Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 (ADA). - Applicable to colleges and universities as employers and educators. 42 USC Sections 12101, et seq. B. Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act of 1973. - Applicable to programs receiving financial assistance from the federal government. 29 USC Sections 794, et seq. C. State Human Rights Laws. - Tend to have lower thresholds of applicability to employment. Coverage of students varies from state to state. II. Prohibited Discrimination Under the ADA A. The ADA prohibits discrimination against a qualified individual with a disability in the following areas: B. - Job application procedures. - Hiring, advancement, or discharge of employees. - Employee compensation. - Job training, and other terms, conditions and privileges of employment. The ADA also prohibits discrimination against persons with disabilities in your educational programs and activities. III. ADA’s Definition of Disability: A. “a physical or mental impairment that substantially limits one or more of the major life activities of an individual”; or B. “a record of such an impairment”; or C. “being regarded as having such an impairment.” _______________ The research assistance of Matthew Smith, 3L, Southern Illinois University School of Law, is gratefully acknowledged. 2 D. The definition is the same as that found in § 504 of the Rehabilitation Act. E. Learning and working are defined as “major life activities,” 45 C.F.R. Section 48(j)(2)(ii). F. Mitigating measures must be considered in making the determination of disability for ADA purposes. Sutton v. United Airlines, Inc., 119 S.Ct. 2139 (1999). The imposition of a physical or mental requirement by an institution does not mean it viewed individuals who could not meet that requirement as disabled. Rather, the ADA is violated only when the institution bases an adverse employment or academic program decision on a “real or imagined” impairment that is regarded as substantially limiting a major line activity. Sutton at 2150. IV. ADA’s Definition of Qualified Individual with a Disability: A. Employment: “An individual with a disability who, with or without reasonable accommodation, can perform the essential functions of the employment position that such an individual holds or desires.” B. 1. Employer must define “essential functions” in job descriptions. 2. Job descriptions may include psychological attributes. Education: “with respect to post-secondary and vocational education services, a handicapped person who meets the academic and technical standards requisite to admission or participation in the recipient’s education program or activity.” 45 C.F.R. 84(3)(k)(3). 1. Like “essential function”, the fundamental components of a program must be defined. These can include requirements for admission and specific courses. E.g. Aloia v. New York Law School, 1988 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 7769 (S.D.N.Y. 1988), holding that a law school’s refusal to waive its minimum GPA requirement for a student with “central nervous system metabolic disorder” was not unreasonable or discriminatory where “law school has an obvious interest in maintaining meaningful academic standards” and “to preserve the school’s reputation.” 3 C. Fundamental alterations of a program are not required. A person is not “otherwise qualified” if they lack the requisite skills for the program. Southeastern Community College v. Davis, 442 U.S. 397 (1979). Davis defined an “otherwise qualified person” as “one who is able to meet all of a program’s requirements in spite of his handicap.” Id., at 406. V. VI. ADA Exclusions: A. Homosexuality and bisexuality; B. Smoking; C. Sexual behavior disorders; D. Compulsive gambling, kleptomania, or pyromania; E. Disorders resulting from current illegal use of drugs; F. Alcoholism manifesting itself in job performance problems. G. Short-term disabilities. Drug and Alcohol Use A. Don’t discriminate for the prior use of drugs or alcohol. B. Nothing in the ADA prohibits employers from: 1. Prohibiting the use of illegal drugs and alcohol at work; 2. Prohibiting employees from being under the influence of alcohol or illegal drugs at work; 3. Disciplining employees for poor performance or absenteeism caused by alcohol or illegal drug use; 4. VII. Conducting drug tests and using the results for disciplinary action. Reasonable Accommodation A. Employment: 1. Employer needs to consider reasonable accommodation. 2. Employee responsible for requesting accommodation. 3. Reasonable accommodation determined on individual basis. 4. Factors include nature of disability and job or program requirements. 4 5. Consult with employee to assess job-related limitations and how they might be overcome. 6. Employer determines the accommodation. 7. Accommodation need not be the best available. 8. Be creative in exploring accommodations for employees and clients. 9. Accommodation need not be provided if it would impose an undue hardship. 10. Undue hardship occurs when a proposed accommodation is: 11. B. a. unduly expensive b. unduly disruptive c. a fundamental alteration of a program or operation Undue hardship linked to employer’s size and financial resources. Education 1. Colleges and universities are required to make reasonable accommodations on an individually determined basis. Section 504 regulations encourage accommodations such as: a. Changes in the length of time permitted for the completion of degree requirements; b. substitution of specific courses required for the completion of degree requirements, and c. adoption of the manner in which specific courses are conducted. 34 C.F.R. § 104.44(a). 2. Essential requirements can be imposed. “Academic requirements that the recipient can demonstrate are essential to the program of instruction being pursued by such student or to any directly related licensing requirement will not be regarded as discriminatory within the meaning of this section. Id. 3. Frequently requested accommodations: a. Tutors: Normally not required as personal services are not contemplated under the ADA. But if generally available, they must be provided in a non-discriminatory manner. b. Modification of course requirements: If alteration would alter the essential or fundamental nature of the program, change is not required. E.g. Zulke v. The Regents of the University of California, 166 F.3d 1041 5 (9th Cir. 1999). The university, which offered a number of accommodations to a student with a reading disability, was not obliged to change her clerkship responsibilities and schedule. See also Amir v. St. Louis University, 184 F.3d 1017 (8th Cir. 1999). See generally, M. Kay Runyan and Joseph F. Smith, Jr., Identifying and Accommodating Learning Disabled Students, 41 J. Legal Educ. 317 (1991). c. Modification of Testing Procedures: Office for Civil Rights regulations require institutions to provide testing methods that evaluate students with sensory, manual, or speaking impairments so as to best insure that the results of the evaluation represents the student’s achievement, rather than the disability. 34 C.F.R. 104.44(c). 1. Modification of Examination Procedures: This is the most frequently requested accommodation. In a survey of the 1994-95 academic year, 1187 students from 80 law schools requested accommodations on exams, with 54% doing so on the basis of a learning disability. Donald Stone, The Impact of the Americans with Disabilities Act on Legal Education and Academic Modifications for Disabled Law Students: An Empirical Study. 44 Kan. L. Rev. 567 (1996). 2. Modification Cases: a. Ware v. Wyoming Board of Law Examiners, 973 F.Supp.1339 (D.Wyo.1997). A person with MS claimed the Wyoming Examiners violated the ADA by refusing all of her requested accommodations. The examiners had made significant accommodations to allow Ms. Ware to take the bar exam. In granting summary judgment, the Court held that the ADA did not pre-empt the state’s bar examination rules and that the accommodations proposed were reasonable. b. Murphy v. Franklin Pierce Law Ctr., No. 95-1003, 1995 WL 325791, *3 (1st Cir. May 31, 1995) (unpublished opinion). In this case, the court held that accommodations, which included an extra hour in which to complete her exams, satisfied the law school’s obligation to provide a reasonable accommodation. 6 c. McGregor v. Louisiana State University, 3 F.3d 850 (5th Cir. 1993), held that the law school had accommodated a wheel-chair bound law student by granting the student permission to eat and drink in the room to maintain his sugar level and allowing him 8 hours instead of the usual 4 hours to complete his exam. VIII. Additional Resources: - Laura Rothstein, Disabilities and the Law (2nd Ed. 1997). - Kevin H. Smith, Disabilities, Law Schools, and Law Students: A Proactive and Holistic Approach, 32 Akron L. Rev. 1 (1999). - James Leonard, Judicial Deference to Academic Standards Under Section 504 of the Rehabilitation Act and Titles II and III of the Americans with Disabilities Act, 75 Neb. L. Rev. 27 (1996). - Alfreda A. Sellers Diamond, L.D. Law: The Learning Disabled Law Student as a Part of a Diverse Law School Environment, 22 S.U.L. Rev. 69(1994) - Wynne v. Tufts University School of Medicine, 932 F.2d 19(1st Cir. 1991). - Prior Stetson Conference outlines. - NACUA Publications. Contact nacua.org. 7