Canada Making a Difference in Egypt through CIDA – Improving

advertisement

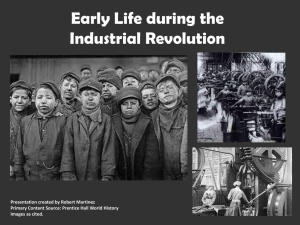

Canada Making a Difference In Egypt through CIDA Part 1: Improving Brick Factories to Save Lives Canadians are making a difference in many parts of the world, through organizations such as the Canadian International Development Agency (CIDA); an organization that supports sustainable development in developing countries in order to reduce poverty and to contribute to a more secure, equitable, and more prosperous world. In Egypt, CIDA is engaged in projects that tackle both societal and environmental issues. These projects and initiatives are improving the lives of many Egyptians in different parts of the country. In Cairo, CIDA introduced its Climate Challenge Initiative about 2.5 years ago. Although this project just ended in May 2006, its success and its impact are still very much seen. Cairo, with a population of nearly 20 million, suffers greatly from air pollution. It is known as one of the most polluted parts of the world, along with cities such as New Delhi, Tokyo and Mexico City. With this in mind, CIDA implemented its Climate Change Initiative to help improve the climate. The aim of this initiative was to reduce Green-House-Gas (GHG) emissions by converting 50 brick-making factories on the outskirts of Cairo from burning a heavy-oil called mazot to burning natural gas as the production fuel. When factories burn mazot, the pollutants released in the emissions are hazardous to the environment and the people. Some of the chemicals released in the emissions contribute to skin disorders, respiratory illnesses such as asthma and pneumonia and certain kinds of cancers. They also affect the agricultural life as they contribute to the increased mortality for natural plants and animals. Once these 50 factories changed to natural gas, these problems were reduced. CIDA worked with these 50 factories, an Egyptian government agency (the Egyptian Environmental Affair Agency), a natural gas company and other secondary players, some of which were involved in designing the burners for the factories. While this initiative was a revolution for these brick factories, it also proved to be a challenge to CIDA since they had to bring all stakeholders together and provide technical support simultaneously. But thankfully, these challenges were overcome and the project has been a success. Its success can be seen through the positive environmental changes as well as the replication of this pilot project, which is currently being organized. A study conducted to evaluate the impact of this conversion indicates that there is improved air quality and cancer risks for many chemicals have been reduced by over 90%. As well, other health risks for many chemicals have been reduced by over 80%. Humans, animals and crops are all benefiting from this conversion as they are inhaling fewer pollutants. There is also the plan to implement a large-scale brick factory conversion program in Egypt through the leveraging of Canadian private-sector investment. This new initiative will convert over 200 brick factories in the Arab Abu Saed and El Saaf areas. Currently, the converted 50 factories emit 100,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide less per year than they were emitting while they were burning mazot. This annual reduction of carbon dioxide emissions is equivalent to 300,000 vehicles on the streets of Cairo. This conversion has also proven to be economically viable as the factories continue to make profits. Through such projects, made available through Canadian funds, Canada is changing lives by improving the environment. Canadians should be very proud of what Canada is doing in the world. According to Eman Omran, the SME Program Team Leader of CIDA, implementing such projects leave a very positive impression of Canada to the government of Egypt and this is because Canada is known for working openly, taking risks and sharing information. “The government trusts Canada and often asks Canada for its assistance in different programs,” she further said. “When people see the results, they are impressed and start replicating the models that are introduced by our projects,” says Eman. Mr. Mamdouh Afia, the former Project Monitor who monitored this project on behalf of CIDA, took me to one of the brick factories to see how these factories function. We drove to Arab Abu Saed, which lies in the outskirts of Cairo in the desert, where over 200 brick factories are located. As we approached the factories, I saw two kinds of smoke emissions released into the atmosphere from the hundreds of chimneys. While some was white in colour, the majority of the emissions were black. Mamdouh soon told me that the white emissions, which are made of pure water vapour, come from the factories using natural gas, with the black emissions released from mazot-burning factories. “Just by converting one chimney into burning natural gas instead of mazot, you save the health of at least 50 people,” said Mamdouh. When we walked into one of the factories, I saw number of young people working; all of which are male. While many of them are in their mid to late teenage years, some are younger than that. The young ones, between the ages of 11to 13, were full of smiles and very cheerful. As I spoke to them, it became clear to me that these children are working here because they do not want to see their families starve. It’s their way of life and they accept it wholeheartedly; they make their days worthwhile by having fun together while working. The factory owner, Mr. Salah Abu Ghor, told me that most of his workers, irrespective of age, work and live at the factory for five days straight; they get two to three days off, where many of them go back to their towns or villages to visit their families. He also told me that there are no discrepancies in their wages from factory to factory; all brick factory workers of this area make the same level of wages. As we stood under the sun of Cairo, the young boys wanted me to take pictures of them with their bricks on their backs. They were all smiling, which made me see life in a different light. If I had bricks on my back, in that kind of hot climate, I don’t think I’d be smiling. They work hard and they are happy. A young man by the name of Khalil Mesleh, 12, is responsible for transporting bricks to and from the burning section of the factory with a donkey. “I have to work because my father died and I want to help my mother,” he told me. The eldest in his family, he spends Wednesdays, Thursdays and Fridays at his house, which is 20 km from the factory. The remainder of the week is spent working. “But I go to school,” he said, “when school opens in one month, I will stop working because I need to go to school.” Mahmoud Abdulaziz is a 19 year old university student, studying agriculture. He works at the factory to save money for his tuition fees. It’s a summer job for him. Hameed Abdulwahid, 11, comes to work with his father to pick up the broken bricks. “It is a very important job,” he says joyfully, “I will take over my father’s job when I am big.” From the two hours I was there, I saw how the workers stick together. They are all friends and they have a good time working together. When they’re not working, they play football together, eat together and live together.