Paranoid Cognition in Organizations:

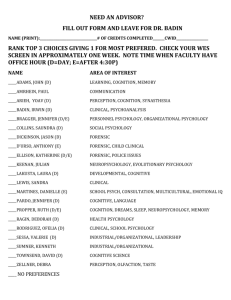

advertisement