Chapter 10 – Summary

advertisement

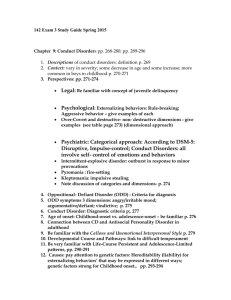

Chapter 10 – Summary Mood disorders involve disabling disturbances in emotion. DSM-IV-TR lists major depression and bipolar disorder as the two principal kinds of mood disorders. In major, or unipolar, depression, a person experiences profound sadness as well as related problems such as sleep and appetite disturbances and loss of energy and selfesteem. Bipolar I disorder may include depression but also is characterized by mania. With mania, mood is elevated or irritable, and the person becomes extremely active, talkative, and distractible. The person with bipolar I disorder may have episodes of mania alone, episodes of mania and depression, or mixed episodes, in which both manic and depressive symptoms occur together. DSM-IV-TR also lists cyclothymia and dysthymia as the two chronic mood disorders in which symptoms are not considered sufficient to warrant a diagnosis of major depression or bipolar disorder. In cyclothymia, the person has frequent periods of depressed mood and hypomania, a change in behavior and mood that is less extreme than full-blown mania. In dysthymia, the person is chronically depressed. Psychological theories of depression have been couched in psychoanalytic, cognitive, and interpersonal terms. Psychoanalytic formulations stress a fixation in the oral stage that leads to a high level of dependency and an unconscious identification with a lost loved one whose desertion of the individual has resulted in anger turned inward. Beck's cognitive theory ascribes causal significance to negative schemas and cognitive biases and distortions. According to helplessness/hopelessness theory, early experiences in inescapable, hurtful situations instill a sense of hopelessness that can evolve into depression. Such individuals are likely to attribute failures to their own general and persistent inadequacies and faults. Interpersonal theory focuses on the problems depressed people have in relating to others and the negative responses they elicit from others. Psychological theories applied to the depressive phase of bipolar disorder are similar to those proposed for unipolar depression. The manic phase is considered a defense against a debilitating psychological state, such as low self-esteem. Biological theories suggest that there may be an inherited predisposition for mood disorders, particularly for bipolar disorder. Early neurochemical theories related depression to low levels of serotonin and bipolar disorder to varying levels of norepinephrine (high in mania and low in depression). Recent research has focused on the postsynaptic receptors rather than on the amount of the various transmitters. Overactivity of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis is also found among depressive patients indicating that the endocrine system may also influence mood disorders. Several psychological therapies are effective for depression. Psychoanalytic treatment tries to give the patient insight into childhood loss and feelings of inadequacy and selfblame. The aim of Beck's cognitive therapy is to uncover negative and illogical patterns of thinking and to teach more realistic ways of viewing events, the self, and adversity. Interpersonal therapy, which focuses on the depressed patient's social interactions, can also be effective. Psychological therapies show promise in treating bipolar patients as well. Biological treatments are often used in conjunction with psychological treatment and can be effective. Electroconvulsive shock and several antidepressant drugs, such as tricyclics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors, and MAO inhibitors, have proved successful in lifting depression. Also, some patients may avoid the excesses of manic and depressive periods through careful administration of lithium carbonate. DSM-IV-TR diagnoses of mood disorders in children use the adult criteria but allow for age-specific features, such as irritability and aggressive behavior, instead of or in addition to a depressed mood. Self-annihilatory tendencies are not restricted to those who are depressed. Although no single theory is likely to account for the wide variety of motives and situations behind suicide, a good deal of information can be applied to help prevent it. Most perspectives on suicide regard it as an act of desperation to end an existence that the person feels is unendurable. Most large communities have suicide prevention centers, and at one time or another, most therapists have had to deal with patients in suicidal crisis. Suicidal persons need to have their fears and concerns understood but not judged. Clinicians must gradually and patiently point out to them that there are alternatives to self-destruction.