Disclaimer - American Society of Exercise Physiologists

advertisement

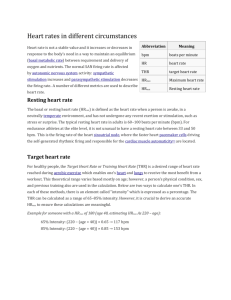

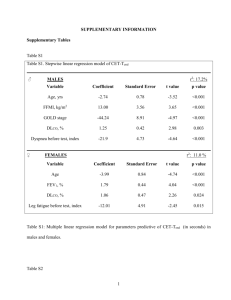

19 Journal of Exercise Physiologyonline February 2013 Volume 16 Number 1 Editor-in-Chief Official Research Journal of Tommy the American Boone, PhD, Society MBA of Review Board Exercise Physiologists Todd Astorino, PhD ISSN 1097-9751 Julien Baker, PhD Steve Brock, PhD Lance Dalleck, PhD Eric Goulet, PhD Robert Gotshall, PhD Alexander Hutchison, PhD M. Knight-Maloney, PhD Len Kravitz, PhD James Laskin, PhD Yit Aun Lim, PhD Lonnie Lowery, PhD Derek Marks, PhD Cristine Mermier, PhD Robert Robergs, PhD Chantal Vella, PhD Dale Wagner, PhD Frank Wyatt, PhD Ben Zhou, PhD Official Research Journal of the American Society of Exercise Physiologists ISSN 1097-9751 JEPonline Is the HRmax=220-age Equation Valid to Prescribe Exercise Training in Children? Emilson Colantonio1, Maria Augusta Peduti Dal Molin Kiss2 Federal de São Paulo – Departamento de Biociências, Santos, Brasil, 2Universidade de São Paulo – Departamento de Esportes, São Paulo, Brasil 1Universidade ABSTRACT Colantonio E, Kiss MAPDM. Is the HRmax=220-age Equation Valid to Prescribe Exercise Training in Children? JEPonline 2013;16(1):1927. The estimation of maximum heart rate (HRmax) has been largely based on the formula HRmax=220-age. This equation is well-known in exercise physiology and yet, the formula was not developed from original research. The purpose of this study was to compare the HRmax predicted by the formula and HRmax measured during an exercise test performed to exhaustion in a large range of age group (according to gender and training level). The sample was composed by 145 subjects (74 females and 69 males) that ranged from 7-17 yr, which was divided into pupils (untrained) and swimmers (trained). The data were obtained from a gas analysis system during an incremental treadmill protocol. The subjects’ HR was monitored by ECG while HRmax was estimated using the HRmax=220-age equation. The findings indicated that the equation overestimated HRmax during a maximal incremental test in children and youths. Also, gender and training level were not related to the HRmax, independently if HRmax was predicted or measured. Therefore, the HRmax=220-age equation is not recommended for exercise training in children. Key Words: Cardiovascular Function, HRmax, Age-Group 20 INTRODUCTION The estimation of maximal heart rate (HRmax) has been an important feature of exercise physiology and related applied sciences since the late 1930s. It has been largely based on the HRmax=220-age equation, which is presented in textbooks without explanation or citation to original research (22). Even so, according to Robergs and Landwehr (22), the equation is also frequently used in sports medicine and fitness assessments. Heart rate is a widely used cardiovascular measure to assess a person’s hemodynamic response to exercise or recovery from exercise, as well as to prescribe exercises intensity. The increase in HR during incremental exercise reflects the increase in cardiac output and oxygen to the peripheral tissues. HRmax is the highest HR a person can achieve during maximum exercise (14,16). This is an especially important point, given that the HR does have a maximal value. Hence, since HRmax cannot be exceeded despite a continued increase in exercise intensity and/or training adaptations, it can be used to gauge submaximal exercise intensity (2,12,15). It can also be used in combination with resting HR to estimate maximal oxygen uptake (VO2 max). Interesting, during the last several decades, there has been a marked increase in the number of sport performances with more young athletes. Swimming is included among these sports through the establishment of the world and Olympic records performed by athletes who are still developing (6). The number of children competitions has significantly increased over the past two decades, which has favored the breaking of world records 14-yr old athletes. While the metabolic and functional responses of exercise in adults, whether normal or with impairments are well-known, there are many issues yet to be fully understood in regards to the physical training of children (4,7,8,10,18,19,20,23). Despite the importance and widespread use of the HRmax equation among adults, the validity of the equation remains to be established in children and adolescents. The purpose of this study was to compare the HRmax predicted by the HRmax=220-age equation and HRmax measured during an exhaustive exercise test (i.e., HRpeak) in a large age range according to gender and training level. METHODS Subjects The sample was composed of 145 subjects (74 females and 69 males) that ranged from 7-17 yr. The subjects were divided into pupils (untrained) and swimmers (trained) groups (Table 1). The untrained group consisted of pupils from three state schools of São Paulo city, who participated in physical education classes. They were not involved in sports training. The trained group consisted of children and youth from the same swimming club, who in addition to the physical education classes at their schools, were also involved in regular swim training for at least 1 yr. The swimmers participated in local, state, national, and international swimming competitions. Procedures The anthropometrical measurements, resting electrocardiogram, and treadmill (Inbrasport® ATL) functional test were performed to determine cardiorespiratory fitness. The peak oxygen uptake (VO2 peak) values were obtained using the VO2000 Medgraphics® gas analysis system during an incremental adapted Bruce et al. protocol (5). Criteria for stopping the treadmill tests were: (a) an abrupt increase in systolic blood pressure; (b) a disproportionate increase in diastolic blood pressure; (c) adverse changes on the electrocardiogram; (d) HR values close to the estimated HRmax; (e) the subject’s indication of exhaustion. HR was monitored continuously by the Ergo PC 13 Micromed® electrocardiograph (Micromed Biotechnology, Br). HRmax was estimated by the 220-age equation. 21 Arterialized capillary blood samples were collected from ear lobe at the end of the exercise using Accusport® Lactate Portable Analyzer (Boehringer Mannhein). The data were collected during stable laboratory conditions in regards the temperature (21˚C) and barometric pressure. All treadmill tests were performed during the afternoon period according to the swimmers training time. The experimental protocol was conducted in accordance with the guidelines in the Declaration of Helsinki, and was formally approved by the local Ethics Committee (No. 13031623). The purpose of the study was carefully explained to each subject and his/her parents, as well as obtaining a written informed consent. Table 1. Physical Characteristics of the Subjects. Groups Gender Pupils Female Pupils Male Swimmers Female Swimmers Male Age-Group (yrs) Height (cm) Body Mass (kg) SF (mm)* HR peak (beats·min-1) Lactate peak (mM) 7 - 10 (N = 12) 130.82 ± 8.71 27.97 ± 6.39 66.41 ± 37.44 171.92 ± 22.80 3.60 ± 1.06 11 - 14 (N = 14) 151.51 ± 8.92 42.04 ± 11.22 89.98 ± 35.01 182.29 ± 15.52 4.28 ± 1.13 15 - 17 (N = 14) 161.54 ± 3.50 59.91 ± 10.58 157.66 ± 43.00 179.71 ± 19.34 6.83 ± 2.28 7 - 10 (N = 12) 130.02 ± 5.88 27.56 ± 2.94 46.46 ± 14.49 170.33 ± 13.98 3.72 ± 1.24 11 - 14 (N = 15) 153.97 ± 11.17 46.05 ± 12.06 65.29 ± 27.63 183.67 ± 12.82 5.37 ± 1.96 15 - 17 (N = 9) 175.89 ± 8.52 64.47 ± 13.75 70.99 ± 52.51 187.00 ± 9.45 5.93 ± 2.76 7 - 10 (N = 13) 134.91 ± 7.83 31.76 ± 8.49 76.11 ± 48.72 182.08 ± 16.90 4.28 ± 1.37 11 - 14 (N = 12) 157.88 ± 7.66 52.03 ± 6.98 82.54 ± 23.45 186.00 ± 12.12 5.46 ± 2.49 15 - 17 (N = 9) 161.41 ± 6.92 55.58 ± 4.12 106.42 ± 28.86 177.00 ± 9.22 6.87 ± 2.08 7 - 10 (N = 13) 137.22 ± 10.36 34.58 ± 8.49 40.15 ± 12.76 180.77 ± 16.94 4.85 ± 1.95 11 - 14 (N = 13) 157.48 ± 9.50 45.08 ± 8.04 47.45 ± 12.31 186.69 ± 13.26 7.15 ± 2.25 15 - 17 (N = 9) 174.46 ± 7.82 69.28 ± 11.10 65.39 ± 23.39 184.67 ± 11.48 7.84 ± 2.17 Values are means ± SD. *SF = Sum of 7 Skinfolds. Statistical Analysis The data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (a general linear model). Statistical significance was accepted at P<0.05. 22 RESULTS Mean and standard deviation of difference between estimated HRmax and measured HRpeak, according to gender and training level were: female untrained 23.85 (13.61); female trained 25.76 (13.87); male untrained 27.94 (15.80); male trained 24.06 (15.23); total untrained 26.23 (14.95); total trained 24.90 (14.49) beats·min-1. The summaries of the difference between HR estimated and HRpeak according to gender and training group are presented in Table 2. Table 2. Summaries of the Difference Between HR Estimated and HR Peak, According to Gender and Training Group. Gender Group Mean SD Minimum Maximum Female untrained 23.85 13.61 -6.00 55.00 trained 25.76 13.87 -6.00 57.00 Total 24.93 13.68 -6.00 57.00 untrained 27.94 15.80 -1.00 63.00 trained 24.06 15.23 4.00 65.00 Total 26.03 15.54 -1.00 65.00 untrained 26.23 14.95 -6.00 63.00 trained 24.90 14.49 -6.00 65.00 Total 25.53 14.67 -6.00 65.00 Male Total The training level of the subjects did not promote important changes in the difference between HR for the female group and the male group, as well as in total values. But, it is important to emphasize that the differences can reach high levels as indicated in the maximum column values (55-65 beats·min-1). The boxplot illustrates the tendency for high levels from the Table 2. It is possible to observe the difference of HR between untrained and trained groups for female and male subjects (Figure 1). Figure 1. Difference between HR estimated and HR peak, according to gender and training group. 23 The overview about the dispersion of the points from HR estimated and HR peak data over age (yrs) is showed in the Figure 2. It seems that with increase in age the general difference of HR decreases. Figure 2. HR estimated and HR peak by age. According to the general linear model, the results indicated that there was no relationship between HR and gender, training level or the interaction of them. But, age did indicate a relationship with these differences and, the reduction rate of HR was 1.76 units per year (Table 3). Thus, only age (P=0.001) was significant to the HRmax prediction for gender (P=0.969); for training level (P=0.342); for gender and training level interaction (P=0.454), respectively. Independently of gender and training level, the HRmax increases with age until 12-14 yrs old, and after this point the HRmax begins to decline as a function of the subjects’ age. The difference between HR estimated and HRpeak ranges from around 50 beats·min-1 at 7 yrs old to around 20 beats·min-1 at 14 to 17 yrs old. Table 3. Adjustment Results of Linear Normal Model from Data. p-value coefficient confidence interval Age 0.001 -1.76 Gender 0.969 - - - Training level 0.342 - - - Interaction (gender, training) 0.454 - - - -2.54 -0.98 24 DISCUSSION There is statistical evidence that the HRmax=220-age prediction equation is biased for adults in both men and women (11,26). Tanaka and colleagues (26) reported that the equation underestimates HRmax in older adults. Gellish et al. (11) demonstrated that 220-age equation overestimated HRmax in both genders under the age of 40 and underestimated HRmax for those over than 40. These results have the effect of underestimating the true level of physical stress imposed during exercise testing and the appropriate intensity of prescribing an exercise program for elderly people. In another cross-sectional study involving elderly women (67.1 ± 5.16 yrs) and comparing measured and predicted HRmax values (using the 220-age and Tanaka et al. formulas), the authors concluded that both prediction equations significantly overestimated HRmax measured during a maximal graded exercise test (25). Health Studies Not only is the HRmax=220-age equation used with healthy subjects, it is also used to determine if the attainment of at least 85% of age-predicted HRmax and/or at least 25,000 as the product of maximal heart rate and systolic blood pressure to indicate the exertion level during exercise stress testing in male and female patients (49.3 ± 11.9 yrs) with symptoms suggestive of myocardial ischemia. The results reported by Pinkstaff and colleagues (21) indicate that the use of percentage of age-predicted HRmax was ineffective in quantifying a patient’s level of exertion during exercise stress testing. Heart Rate Children Studies Regarding health studies that involved children and adolescents, one of the recent studies was led by Verschuren et al. (27). The purpose of their study was to provide HRmax values for ambulatory children with cerebral palsy. They determined the effects of age, sex, ambulatory ability, height, and weight on HRmax. No associations were found between HRmax and any of variables. Since the HRmax equation did not vary with age, the authors concluded that the equation was (220-age) was not appropriate to use with these subjects. There are really few studies in the literature that have investigated the use of predicted HRmax and its in children and adolescents (9). In a recent study, the researchers analyzed the validity of two HRmax prediction equations “220-age” and “208-(0.7 x age)” in boys who were 10 to 16 yrs of age. They concluded that the HRmax=220-age equation overestimated the measured HRmax and was not valid for this population (17). Their finding agrees with the present study that evaluated boys and girls from 7 to 17 yrs of age. Both studies confirm that the 220-age equation overestimated HRmax in the children and adolescent, independently of gender and training level. The biggest differences occurred between 7 to 12 yrs of age. The difference between the HRmax prediction and the HRpeak measured decreased 1.76 units by year in the 7 to 17 yr age-group. Exercise Prescription for Children According to Rowland and Green (24), the ability of children to respond to endurance training with increased aerobic capacity is unclear. The pre-pubertal subjects may require a higher target HR than adults to increase VO2 max. In their study, the HR response at the anaerobic threshold was measured non-invasively as the ventilatory breakpoint (VBP) during treadmill testing of 12 premenarchal girls to establish a metabolic based target HR. Their results indicated that the rates at the VBP exceeded those predicted by the standard formulas for calculating target HR in adults by over 10 beats·min-1 in the majority of the girls. These data also indicate that the HR guidelines designed for training older individuals may not adequately stress oxygen delivery systems in pre-pubertal subjects. There are additional considerations in addition to HR variability that influence HR during exercise, such as day- 25 to-day variability in HR, cardiovascular drift, hydration status, and environmental factors, including temperature and altitude (1). Aquatic Sports and Heart Rate In aquatic sports like swimming, another physiological aspect is the water immersion inducing various changes in the cardiovascular system that includes a decrease in HR (3,13). The theory of this phenomenal might be explained by the increase in central blood volume through the redistribution of venous blood and extra cellular fluid from the lower extremity to the upper part of the body in the same way as during the face immersion reflex with an increase in plasmatic volume in the central part of the body. Thus, the heart and central circulation are distended, leading to stimulation of volume and pressure receptors of these tissues, which in turn leads to a new adaptation of cardiovascular system, increasing central venous pressure, cardiac output and stroke volume, and finally lowering HR (28). In other words, with respect to the present study and, in particular, the trained group who swimmers between the age of 7 and 17, it is important to point out that the use of HR to prescribe swimming training for children and adolescents is likely to be problematic when the HRmax=220-age equation is used. Therefore, it is essential that the swim coaches are fully informed of the limitations in using the HRmax values to prescribe the intensities of swim training during the season. CONCLUSIONS Based on these results, it is reasonable to conclude that the 220-age equation overestimates children and adolescents HRmax. In addition, the gender and training level were not related with the HRmax. Thus, the HRmax=220-age equation is not recommended for exercise training prescription in children and adolescents. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS We would like to thank the children and teenagers who volunteered to participate in this study. Address for correspondence: Emilson Colantonio, Departamento de Biociências, Universidade Federal de São Paulo, Santos, Brasil; email: colantonio@unifesp.br REFERENCES 1. Achten J, Jeukendrup AE. Heart rate monitoring – Applications and limitations. Sports Med. 2003;33(7):517-538. 2. American College of Sports Medicine. ACSM's Guidelines for Exercise Testing and Prescription. 8th Edition. American College of Sports Medicine. 2009. 3. Andersson JPA, Line’r MH, Fredsted A, Schagatay EKA. Cardiovascular and respiratory responses to apneas with and without face immersion in exercising humans. J Appl Physiol. 2004;96:1005-1010. 4. Bar-Or O. The Child and Adolescent Athlete. 1st Edition. Oxford: Blackwell. 1996. 26 5. Bruce RA, Kusumi F, Hosmer D. Maximal oxygen intake and nomographic assessment of functional impairment in cardiovascular disease. Am Heart J. 1973;85:546-542. 6. Colantonio E. Detection, Selection and promotion of sport talent: Considerations about swimming. Braz J Sci Movement. 2007;15(1):127-135. 7. Colantonio E, Barros RV, Kiss MAPDM. Oxygen uptake during Wingate tests for arms and legs in swimmers and water polo players. Braz J Sport Med. 2003;9(3):141-144. 8. Colantonio E, Costa RF, Colombo E, Böhme MTS, Kiss MAPDM. Evaluation of physical growth and performance in children and adolescents. Braz J Phys Activ Health. 1999;4:1729. 9. Colantonio E, Lima JRP, Kiss MAPDM. Is the estimating maximum heart rate equation valid to prescribe exercise sport exercise training in children and youth? In Cable NT and George K, editors. Book of Abstracts 16th Annual Congress of European College of Sports Sciences; 2011;Jul 6-9:Liverpool, United Kingdom. German: ECSS, p. 527. 10. Del Nero E, Yazbeck Jr P, Kedo HH, Kiss MAPDM, Juliano Y, Moffan PJ. Effect of metoprolol duriles in chronic coronary insufficiency. Arq Bras Cardiol. 1985;45(3):211-216. 11. Gellish RL, Goslin BR, Olson RE, McDonald A, Russi GD. Longitudinal modeling of the relationship between age maximal heart rate. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2007;39:822-829. 12. Heyward VH. Advanced Fitness Assessment and Prescription. 6th Edition. Champaign: Human Kinetics. 2010. 13. Jay O, Christensen JPH, White, MD. Human face-only immersion in cold water reduces maximal apnoeic times and stimulates ventilation. Ex Physiol. 2007;92:197–206. 14. Karvonen MJ, Kentala E, Mustala O. The effects of training on heart rate: A longitudinal study. Med Exp Biol Fenn. 1957;35(3):307-315. 15. Karvonen MJ, Vuorimaa T. Heart rate and exercise intensity during sports activities – Practical application. Sports Med. 1988;5:303-312. 16. Lusk G. The Elements of the Science of Nutrition. 1st Edition. Philadelphia, PA: W. B. Saunders, 1928. 17. Machado FA, Denadai BS. Validity of maximum heart rate prediction equations for children and adolescents. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2011;97(2):136-140. 18. Matveev LP. Preparação Desportiva. 1st Edition. Londrina: Centro de Informações Desportivas; 1996. 19. McArdle WD, Katch FI, Katch VL. Exercise Physiology: Energy, Nutrition and Human Performance. 6th Edition. Baltimore, MD: Williams & Wilkins. 2006. 27 20. Negrao CE, Pereira Barreto AC. Physical training effects on heart failure: Anatomic, homodynamic and metabolic implications. Journal of Cardiology Society São Paulo State. 1998;8:273-284. 21. Pinkstaff S, Peberdy MA, Kontos MC, Finicane S, Arena R. Quantifying exertion level during exercise stress testing using percentage of age-predicted maximal heart rate, rate pressure product, and perceived exertion. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85(12):1095-10100. 22. Robergs RA, Landwehr R. The surprising history of the “HRmax=220-age” equation. JEPonline. 2002;5(6):1-10. 23. Rowland TW. Developmental Exercise Physiology. 2nd Edition. Champaign: Human Kinetics. 2005. 24. Rowland TW, Green GM. Anaerobic threshold and the determination of training target heart rates in premenarchal girls. Pediatr Cardiol. 1989;10(2):75-79. 25. Silva VA, Bottaro M, Justino MA, Ribeiro MM, Lima RM, Oliveira RJ. Maximum heart rate in Brazilian elderly women: comparing measured and predicted values. Arq Bras Cardiol. 2007;88(3)314-320. 26. Tanaka, H, Monahan KD, Seals DR. Age-predicted maximal heart rate revisited. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2001;37:153-156. 27. Verschuren O, Maltais DB, Takken T. The 220-age equation does not predict maximum heart rate in children and adolescents. Dev Med Child Neurol. 2011;53(9):8614. 28. Watenpaugh DE, Pump B, Bie P, Norsk P Does gender influence human cardiovascular and renal responses to water immersion? J Appl Physiol. 2000;89:621–628. Disclaimer The opinions expressed in JEPonline are those of the authors and are not attributable to JEPonline, the editorial staff or the ASEP organization.