A Neurotheological Examination - People at Creighton University

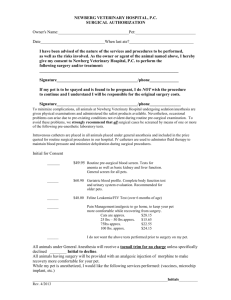

advertisement

Your Brain 1 Running head: NEUROTHEOLOGY Your Brain on God: A Neurotheological Examination Lindsey Goetz Creighton University Your Brain 2 Abstract Neurotheology, or the study of the biological underpinnings to faith in a higher power, emerges as a relatively new player in the theological arena. Although still in its infancy, the discipline bears some contemporary success while demonstrating marked promise for the future. This paper attempts to provide a comprehensive review of the two most prominent bodies of research developed within this topic area, explicating the primary ideologies, methodologies, and findings of J.B. Ashbrook / C.R. Albright and E. D’Aquili /A. Newberg in turn. In an effort to garner an objective approach, a significant discussion of the experimental limitations characteristic of each body of knowledge is likewise provided. Within the current era, neurotheological advancements must inevitably find integration within greater social and political structures. Thus, the paper concludes with a discussion of the ethical, genetic, and theological implications of such work. Your Brain 3 Your Brain on God: A Neurotheological Examination Of all the organs defining the individual, perhaps none emerge as more fascinating than the human brain. It proves hard to imagine that the intricacy and beauty inherent in poetry and political systems, for example, find their roots in what amounts to little more than a few pounds of convoluted gray matter. Yet, despite all of his rational promise, man seems inexplicably driven to seek solace beyond himself, to turn to the cosmos in search of the seemingly unknowable. For thousands of years, such a yearning has occupied the minds of numerous philosophers and theologians, tirelessly laboring to elucidate the relationship between man and the higher power he seems so intent upon seeking. While much has been done to define the nature of the Godrelationship on theoretical grounds, until recently, there have been few research efforts examining the physiological mechanisms behind humanity’s need to connect with a higher authority. Thus, the newly emergent field of neurotheology holds at its center some daunting, yet exciting, questions. How is it that man’s purely physical brain has evolved the capacity to tap into the spiritual world? What areas of the brain play a role in mystical experiences? What neurological underpinnings compel man to religious faith? These inquiries prove inherently important, as humanity’s understanding of both itself and its place in the world stands contingent upon the elucidation of such issues. It is undoubtedly with these implications in mind that James Ashbrook and Carol Albright (1997) and Eugene D’Aquili and Andrew Newberg (1999) embark upon their neurotheological journey. Paradoxically, every step these research efforts take toward an understanding of the brain-God relationship ultimately serves to humble a limited science before the power of faith. Neurotheological Research Within the emergent field of neurotheology, two primary methodologies predominate, that exemplified by James Ashbrook (1997) and that highlighted by the work of Andrew Newberg Your Brain 4 (1999) in conjunction with his late colleague, Eugene D’Aquili. In many respects, these lines of research prove to be complementary, and thus a sufficient analysis of each serves as a prerequisite for the contribution of an informed opinion to the neurotheological debate. Investigational approach and primary findings of James Ashbrook and colleagues Drawing heavily upon David H. Hubel and Torsten N. Wiesel’s investigation of the nature of highly specific visual response patterns and Roger W. Sperry’s award-winning split-brain research, Ashbrook and his associate, Carol R. Albright (1997), articulate two fundamental presumptions regarding the inter-workings of the human brain, namely, that “we are objectseeking and meaning-making creatures” (p. 8). To understand the implications of such an assertion, one must first turn to the aforementioned work in a bit more detail. Hubel and Wiesel based their studies on the idea of the “umwelt,” in which each species’ unique visual limitations (in conjunction with those of other sensory processes) result in a markedly different perception of external reality (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). For example, Hubel and Wiesel determined that a moving object, a moving object entering the field of vision and then stopping, a decrease in illumination, and a dark spot “shifting against a dark and light background” (p.16) represent the sole visual stimuli drawing a response from the neural system of the frog. (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). The researchers postulated that such an effect may be embedded in “feature detectors,” or groups of cells designed to seek out and respond to specific visual stimuli (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997, p. 16). Studies conducted during the 1990s identifying certain clusters of neural cells within the monkey brain reacting specifically to the presentation of a monkey hand or various orientations of a conspecific face provide corroborating evidence for the existence of such patterned activity in higher mammals (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). Because fruit, tree branches, etc., failed to elicit such selective responses, Ashbrook and Albright (1997) hypothesized that a given species possesses a particular need to forge bonds with conspecifics. Research conducted Your Brain 5 upon day-old infants elevated this assertion to the level of the human species, revealing that a) “‘a face-like pattern elicits a greater extent of [newborn] tracking behaviour than does a non-face-like pattern’” and b) that newborns focus the longest on complex visual stimuli (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997, p. 22). Sperry’s investigation of split-brain patients adds a third tier to this neural model by suggesting that, in addition to a preferential orientation toward humanity and complexity, the human brain feels innately compelled to derive meaning from all that it experiences (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). Working with a 16-year-old boy with severed inter-hemisphere connections, Sperry presented two images, a hen and a winter snow scene, to the teenager in such a manner that the former reached only the left hemisphere of the brain while the latter reached only the right. The investigator then asked his subject to select, from a series of eight representations, the one picture that best matched each of the images before him. Although the boy correctly pointed to a shovel (corresponding to the snow scene) and a chicken head, when asked why he had made the selections he did, he responded as follows, “‘Oh, that’s easy. The chicken goes with the chicken head and you need a shovel to clean out the chicken shed’” (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997, pp. 1011). Because the left hemisphere confers the capacity of speech for most individuals, the boy was able to correctly articulate the connection between the hen and the chicken head forged by his leftbrain. However, the severance of his inter-hemisphere neural pathway prohibited the subject’s leftbrain from accessing the perceptions developed by its counterpart, rendering a direct verbal explanation as to why his left hand had pointed to the shovel impossible (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). Yet, despite this lack of knowledge, the boy’s left-brain nonetheless attempted to infer a connection between what it had indirectly witnessed (via the hand motion) and what it knew directly. The ensuing suggestion that the human brain possesses an inherent yearning to create meaning and forge relationships amongst external stimuli captured the attention of Ashbrook and Your Brain 6 Albright (1997), ultimately joining the preferential search for humanity and complexity as a cornerstone of their neurological model. In light of these findings, Ashbrook and Albright embark upon the neurotheological journey in earnest, hypothesizing that the evolutionary yearnings of the human mind find manifestation in the idea of the Christian God (Rottschaefer, 1999). Specifically, the “cognitive imperative,” or need to know, drives us to attribute purpose and meaning to a “higher power” when such evidence proves lacking within the natural environment. Such an entity emerges as inherently anthropomorphic, they argue, as humanity possesses the innate urge to seek out its likeness in the world. Because we are naturally inclined to search for complexity, we further liken the god-figure to the human form, as the latter bears the highest degree of intricacy that we prove capable of imagining (Ashbrook & Albright, 1997). The investigators adopt a comparative methodology in an attempt to derive support for their hypotheses. Drawing upon neuroscientist Paul MacLean’s conception of a triune brain, in which three evolutionary distinct “reptilian,” “paleomammalian” (i.e. the limbic system), and “neomammalian” neural regions progress hierarchically outward from the brain stem to the neocortex, Ashbrook and Albright (1997) attempt to highlight correlations between the functions of each of these structures and “God’s way of being God.” (pp. 52), the apparent assumption being that the existence of such parallels would prove sufficient for the assertion of the God-brain relationship. Indeed, some points of similarity seem to emerge. Studies conducted with reptiles lacking the “paleomammalian” and “neomammalian” neural regions attributable to their higherorder counterparts reveal a territoriality and hierarchical emphasis that arguably corresponds to a “God who belongs to God’s creatures…[and is understood] as the highest of all” (Rottschaefer, 1999, p. 58). Similarly, the concept of God “as interactive and nurturing,” among others, allegedly reflects the human capacity for empathy and the urge to relate conferred by the inner workings of Your Brain 7 the limbic system (Rottschaefer, 1999, p. 58). Building upon the assumption that the right hemisphere understands the world holistically while the left hemisphere views it sequentially, the authors draw correlations between the “neomammalian” brain and the respective visions of “God as relational” and “God as [a] source of order” (Rottschaefer, 1999, p. 59). Based on these findings, Ashbrook and Albright conclude that the human brain, to one extent or another, possesses the requisite “wiring” necessary for belief in an anthropomorphic higher power. Theoretical and methodological limitations of Ashbrook and Albright’s studies Although the research of Ashbrook and Albright (1997) provides an intriguing glimpse of the contour of the biology-theology barrier, the methodology employed throughout their studies restricts the applicability of their work. Perhaps the most striking oversight, if not erroneous perception, lies in the authors’ limited investigation of the comparison of physiological mechanisms and what might be identified as the Christian God. Although this conception of a higher authority integrates nicely with the supporting neuroscience, the fact remains that numerous cultures do not possess an anthropomorphic vision of God; as Rottschaefer (1999) points out, some forms of Buddhism, for example, embody an impersonal vision of a higher being. Paradoxically, the apparent universality of religion (arguably encompassing a great diversity of the world’s populations) that would seem to suggest the existence of faith-based genetic underpinnings actually serves to weaken Ashbrook and Albright’s argument for a biologicallymediated belief in a higher authority. If our brains always motivate us to seek out human connections in the world, as the authors seem to suggest, then how is it that such historical religions as Buddhism ever managed to emerge? It would seem, then, that the existence of such faiths undermines the validity of Ashbrook and Albright’s work. To be fair, environmental conditions inevitably influence genetic penetrance, and thus it proves theoretically possible that all religiosity found it roots in an anthropomorphic vision of God, and that the genetic predisposition Your Brain 8 to seek a higher power bearing this quality might subsequently have been culturally modified to include, for example, the Buddhist concept of the “Tao.” Yet, this possibility proves unlikely, as there exist no historical records (to the best of my knowledge) testifying to such a transition with respect to any known religious system. Further, as Rottschaefer (1999) indicates, the contention for a biological drive toward the anthropomorphic God rests upon the contingency that individuals having such a conception were more likely to survive than their counterparts bearing impersonal perceptions of a supreme being. Ashbrook and Albright, however, leave this issue untouched and never actively attempt to provide an evolutionary explanation for the theories that they propose. In light of these shortcomings, I am personally inclined to believe that the authors’ work emerges not as fundamentally faulty, but rather that it fails to “dig deep enough” within the evolutionary phylogeny of the brain’s inner circuits to generate a complete picture of humanity’s relationship to God. In other words, Ashbrook and Albright sacrifice, perhaps due to personal religious bias, an inclusive examination of the topic at hand in order to focus their attention upon more recently evolved regions of the brain. The comparison-based methodology utilized by Ashbrook and Albright (1997) imposes additional limitations upon the scientific value of their research. Though the authors likely practice sound neuroscience and bear a sufficient understanding of the nature of a theological oversoul, they depend solely upon correlates between the brain and their vision of God in an effort to establish a relationship between the two. While such speculation bears some suggestive value, the lack of a strong scientific bridge between brain function and the belief in a higher authority does little to resolve the issue of the source of human spirituality. Further, Ashbrook and Albright (1997) readily admit that the use of MacLean’s three-tiered neural model can be problematic in that it proves difficult to isolate the behaviors produced by each individual component. The investigators attempt to combat this ambiguity by adopting a reductionism approach. Rather than Your Brain 9 studying the “reptilian” sector of the human brain directly, for example, they rely upon research conducted using species with access to this neural region alone (i.e. lizards) and then extrapolate the findings to include human processes. While this methodology may bear some general value, no guarantee can speak to the homology of cross-species brain function within a similar neural region. The evolutionary process includes not only the acquisition and specialization of brain matter, as the authors suggest, but a re-working of older neural regions within this newly-emergent framework as well. There is simply no sound reason to imply, for example, that lizards and humans have the same territorial urgings; Ashbrook and Albright (1997) may do more to advocate a neural basis for reptilian spirituality than that of their human counterparts. Fortunately, neurotheology, like most other disciplines, proves to be a highly collaborative effort, and thus the strengths of some studies often compensate for the apparent weaknesses in others. Such a case might well be made here, as the work of Newberg and D’Aquili (2001) offers a fresh perspective on the neurotheological problem. Unlike Ashbrook and Albright (1997), who devote the majority of their studies to the God-relationship, D’Aquili and Newberg expand their examination beyond the neural basis for belief to include other religious aspects such as the specific brain states characteristic of religious experience and ritual. Investigational approach and primary findings of D’Aquili and Newberg Adopting a primary causational approach, D’Aquili and Newberg (1999) root their neurotheological efforts in the fundamental hypothesis that certain evolutionarily beneficial cognitive structures compel the individual to the formulation of the myth, or more specifically to an understanding of a higher authority. These “operators” serve not as specific neural structures within the realm of the physical brain, but rather as functional groupings within the domain of the mind (D’Aquili & Newberg, 1999). The researchers argue that two such structures, the “Causal Operator,” or the human ability to interpret and anticipate the series of cause-effect relationships Your Brain 10 characterizing the external environment, and the “Binary Operator,” or the need to reduce the complex world into a more manageable series of arbitrary opposites such as “up” and “down,” bear particular implications for mythic evolution (Newberg, D’Aquili, & Rause, 2002, p.81). In the case of the former, Newberg et al. (2002) speculate that the drive to understand the causal underpinnings of one’s environment may well have led early peoples to ruminate over the fundamental issue of human mortality. The authors further suggest that the evolutionary survival advantage incurred by one’s incessant need to analyze the exterior world in terms of potential threat relationships may well have solidified the “Causal Operator” within the human psyche, thus rendering early hominids unable to dismiss such existential questions. In the wake of such a perplexing problem, the “Binary Operator” likely intervened, attempting to break the mortality issue down into more modest subsets (Newberg et al., 2002). D’Aquili and Newberg (1999) thus argue that it emerges as no happenstance that most myths bear two common components, “a problem of ultimate concern to a society…[framed] in terms of juxtaposed opposites such as…good-evil, or heaven-hell” and “some resolution…of the seemingly irreconcilable opposites that constitute the problem” (p. 85). In an effort to elucidate this latter process and thus to complete their theory of mythic formation, the authors first turn to a specific analysis of human neurological function as understood through its potential contributions to the more general phenomenon of the religious experience. Newberg et al. (2002) implicate two subsets of the autonomic nervous system as crucial contributors to the “mystical experience,” namely, the sympathetic system, responsible for the arousal states characteristic to hunting and mating behavior, and the counterbalancing parasympathetic system, responsible for energy-conversation as manifest in sleep, digestion, and cell growth. While these “arousal” and “quiescent” systems normally act in an antagonistic fashion, maximal functioning of either component may lead to a “spill-over” in neural activity Your Brain 11 resulting in the simultaneous activation of both systems (Newberg et al., 2002). The authors postulate that it is in such cases that purported mystical experiences emerge. For example, the “hyperquiescent” state achieved through meditation may trigger the activation of the arousal system, resulting in a “burst of energy” that leads one to feel absorbed by an outside object, an experience Buddhists refer to as “Appana samahdi” (Newberg et al., 2002). Or conversely, the researchers assert that a state of “hyperarousal” interrupted by a parasympathetic breakthrough may contribute to the trancelike condition achieved in many religious experiences (Newberg et al., 2002). A second neural complex, the Orientation Association Area (seated within the posterior parietal lobe), also demonstrates ties to such religious moments. According to SPECT imaging studies, the left Orientation Association Area serves to create one’s “spatial sense of self, while the right side creates the physical space in which that self exists” (Newberg et al., 2002, p. 28). One study, in which SPECT images were generated portraying the patterns of neural activity characteristic of a Buddhist monk immersed in meditation, revealed intriguing mystical consequences consistent with such a dynamic (Newberg et al., 2002). Because the subject’s supposedly functioning Orientation Association Area (OAA) demonstrated minimal activity levels during peak meditation times, the researchers postulated that mystical states may produce a neurochemical environment that deprives the OAA of input. Such a condition bears remarkable significance, setting the framework for the blurring of the distinction between the self and external reality characteristic of the unitary nature of many transcendental states (Newberg et al., 2002). Having laid the preceding foundation, Newberg and D’Aquili (2001) return to the issue of the union of opposites necessary for mythic formation. Drawing on the unique left brain-right brain interaction studied by Ashbrook and Albright (1997), the researchers suggest that the “cognitive imperative” compels each hemisphere to seek, respectively, a sequential and holistic solution to the existential problem. Inter-hemispheric agreement eventually occurs, enabling a Your Brain 12 shift from the left-dominant view of the logically irreconcilable opposites of say, heaven and hell, to a right-dominant view in which such opposites are holistically unified (D’Aquili & Newberg, 1999). An electrical impulse follows, triggering a peaceful emotional response from the hypothalamus which then activates the quiescent system. Because the sympathetic system has not yet had time to subside, the result is similar to that of the “hyperarousal breakthrough” condition mentioned above, an effect that the authors suggest may be interpreted as divine revelation (Newberg et al., 2002). Theoretical and methodological limitations of D’Aquili and Newberg’s studies While Newberg and D’Aquili’s analytical approach (2001) offers much insight into evolutionary theory and a broader understanding of man’s relationship to a higher authority, the theoretical and methodological underpinnings of their work nonetheless bear limitations. Even if the adaptive advantages conferred by the various neural structures that the authors implicate in the brain-God pathway prove to be correct, they do not – and cannot – attempt to explain the motivating source behind such an evolutionary process. In other words, their findings exert little impact upon the evolution-creation debate, as the purported gradual emergence of the God-idea within the neural wiring of ancient human brains in no way counteracts the common belief in the eternal nature of a higher being (i.e. God may well have existed all along, even if man only recently evolved the capacity to perceive Him). Further, though D’Aquili and Newberg’s references to mystical experiences, ritualistic acts, and a non-descript higher power render their work more religiously conclusive than that of Ashbrook and Albright (1997), they fail to consider the issue of morality so central to many belief systems. Peters (2001) offers a potential solution for this shortcoming, suggesting that neurotheology might prove more comprehensive were it to approach future studies with the “evolved neurophysiology of moral experience” in mind (p. 495). While neurotheological dependence upon evolutionary ethics may render the brain-God Your Brain 13 relationship more complex, such a compilation inevitably offers the greatest insight regarding the issues in question. A more subtle ideological limitation emerges in D’Aquili and Newberg’s apparent assumption that religious moments are inherently positive. They argue that a key element in mythic formation lies in the pleasurable union of left-brain and right-brain perceptions and highlight the fulfillment that often corresponds to trancelike and meditative states. Yet, the authors devote little-to-no attention to the negative implications of the transcendental moments inherent to many religious systems; long bouts of fasting, for example, hardly prove pleasurable (Woodward, 2001). D’Aquili and Newberg clearly indicate that humans, like all other organisms, possess an innate desire to seek out what they perceive to be in their best survival interest. Thus, the idea that some individuals might have developed the ability to actively accept suffering in pursuit of a spiritual relationship requires further elucidation, an end that future studies might obtain by focusing more specifically upon the pain centers of the brain. Perhaps the greatest fallacy manifest by D’Aquili and Newberg’s work, however, lies in the potential for an overly reductionist approach to religiosity. The argument may well be made that many of the world’s belief systems share some common threads. Yet, overly generalized theological conceptions unduly simplify the beautiful complexity inherent to religious theories. Neurotheology may offer a starting point for the explanation of faith-based yearnings, but the fulfillment of that understanding ultimately comes in corroboration with the input of a multitude of cultural, philosophical, and theological factors. Implications of Neurotheological Research According to the neurotheological research highlighted above, evidence of a fullydeveloped neocortex bearing the neural capacity for consciousness and theory of mind proves sufficient for the establishment of a relationship with God, if that connection is indeed mediated by the brain. There is nothing in this definition to suggest that a potential connection to a higher Your Brain 14 power resides in humanity alone. Newberg and D’Aquili (2001) implicate fear of death as a crucial component driving mythic evolution in prehistoric man. Yet, Poole’s (1998) reference to elephant attempts to raise or feed dying conspecifics and to cover dead comrades with vegetation begs the question as to the existence of non-human God-relationships, especially since the welldeveloped cerebrums and cerebellums of these gentle giants theoretically equips them with the neural “wiring” to make such connections possible. Convergent evolution is hardly a rare phenomenon, and selective pressures might easily have driven more than one species to belief in a higher power. Future studies generating SPECT scans of the brains of “mourning” elephants and other human relatives involved in potential transcendental activities prove absolutely requisite for a complete neurotheological understanding. One need not wait for the end of these studies, however, to see that such possibilities bear extraordinary ethical ramifications within the animal rights arena in terms of poaching, product testing, and euthanasia, to name a few. If animals and humans stand equal before God, then perhaps a re-examination of our definition of “murder,” for example, is in order. Acknowledging the mammalian capacity for a relationship with a higher authority blurs the human / non-human border, forcing philosophical reflections on what truly constitutes “humanity” and threatening the current structure of social systems. An extension of the God-relationship could exert further impact within the theological realm as a universal spirit proves more compatible with most Eastern rather than Western religious traditions. Such discrepancies might well be translated into views of “correctness,” an effect that might well prove detrimental to inter-faith relationships. Neurotheological research likewise provokes substantial considerations within the world of genetics. If the evolutionary roots of religiosity advocated by Newberg and D’Aquili (2001) prove to be correct, than the inference of a universal genetic component for transcendental faith would be valid. Yet, despite a broad inter-population trend toward belief in a higher power, some Your Brain 15 individuals obviously prove more religious than others. The question then becomes, what mechanisms dictate the penetrance and expressivity of “religious alleles,” should they exist? David Wulff’s observation that rational, controlled, and non-fanciful individuals generally suppress religious inclinations indicates that epistasis and inter-genic interactions likely play a role (Underwood, 2001), although such conclusions represent partial explanations at best. After all, genetic theory finds its most basic roots in the concept that specific environmental cues inevitably mediate the genetic expression of a given allele; one’s demeanor could just as easily be the result of environmental conditions as genetic predispositions. Thus, cultural influences contribute significantly to mythic shaping. Current neurotheological research seeking to highlight potential biological connections to a higher being obligates a corresponding effort to elucidate the cultural contributions to religiosity. Yet, to the best of my knowledge, no such “sociotheological” research exists. Comparative studies designed with the specific intent to isolate cultural correlates within various religious traditions might help to balance out current biological strides. One might also employ twin studies. An investigation of the “degree of religiosity” evidenced by monozygotic siblings in cases in which one individual was raised in a theological environment not commonly associated with his or her ethnic background might help to flesh out the faith-culture relationship. In any case, a genetic component for belief in a higher power helps to explain the overwhelming incidence of religious homogony within families, in terms of both preferred ideologies and the degree of passion with which one pursues religious traditions (if the “religiosity alleles” are coinherited with those predisposing an individual to a certain disposition, then the capacity for faith could prove just as consistent as the culturally-influenced choice of tradition among families). Further, although identification of the cultural underpinnings to belief may not necessarily alleviate inter-faith tensions, it might at least help to clarify the source of such animosity and indicate why individuals prove so willing to fight for their beliefs. Your Brain 16 Perhaps the greatest implications of neurotheological research, however, lie in the potential shifting of the scientific relationship with the religious community. Ashbrook, Albright, D’Aquili, Newberg, and many others highlight the role of the mind as an intermediate between the physical domain of the brain and spiritual realm of a higher being. Yet, this condition in no way speaks to the directionality of the man-God relationship. As David Fontana (2003) indicates, “two sets of competing theories as to this relationship, monism (the brain creates [the] mind) and dualism (the mind works through [the] brain) have been argued over from the time of Descartes onwards” (p. 185). Newberg and D’Aquili’s (2001) SPECT imaging studies seem inevitably fated to fuel such controversy. On the one hand, one might assume that a neurological foundation for faith might support the theological assertions of those having mystic experiences. But, as Begley and Underwood (2001) assert, one might find himself or herself equally tempted, on the basis of such evidence, to draw quite the opposite conclusion by inferring that a biological correlate for belief refutes the tenets of religion. Of course, such reasoning need not ensue, as a SPECT scan of one’s “brain on apple pie” would depict a neurological basis for the experience without necessarily refuting the existence of the pie itself (Begley & Underwood, 2001). Despite this contingency, monistic trends nevertheless currently persist (Fontana, 2003). Within this context, religion might indeed feel threatened, as the assertion that the brain gives rise to the mind bears the implication that the latter cannot survive independently of the former (i.e. when the brain dies, the mind must follow suit, and thus the argument for an afterlife deflates). Yet, no proof exists to unequivocally substantiate the assertion that the neurologist’s ability to stimulate nerve cells into provoking a mystical experience ensures that the resultant response mirrors that induced, say, by God. Even D’Aquili and Newberg’s evolutionary foundations for biological belief do not exclude the ability of a divine character to communicate with the individual via the mind, as creationist principles render it possible that man evolved to perceive a God having existed all along. The best that future Your Brain 17 neurotheological research can hope to offer is a clearer understanding of the mind-brain relationship. As Penfield states, “‘Whether there is such a thing as communication between man and God,’ and whether the mind can be energized by an outside source after death ‘is for each individual to decide for himself. Science has no such answers’” (Fontana, 2003, p. 84). Conclusion Neurotheology emerges as an incredibly dynamic discipline. As Ashbrook and Albright (1997) help to elucidate, biological foundations may well help to corroborate one’s understanding of God and the implicit religiosity that accompanies such faith. Their methodological approach, though ultimately speculative, helps to create a comprehensive image of the neurological connections to a specific ideology, namely that manifest by the Christian God. D’Aquili and Newberg take this analysis one step further, putting forth an evolutionary path to a higher authority that may well embody a common heritage for the world’s population. Yet, despite all the promise science bears for future understanding, neurotheology in-and-of-itself will never provide the “missing link” to God that some individuals may anticipate. Such a discipline was never designed with isolationist intents and it is in the ability to augment philosophical, social, and theological transcendent theories that neurotheology gains its greatest strength. A yearning for knowledge and purpose both fundamentally characterize humanity; as long as the latter exists, one will crave the former. While the power of faith in a divine spirit may never be overridden, humanity’s belief in itself proves equally hard to ignore. Thus, with a proper respect for its limitations, neurotheology may serve humanity well far into the future. . Your Brain 18 References Ashbrook, J. B., & Albright, C. R. (1997). The humanizing brain: Where religion and neuroscience meet. Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press. Begley, S., & Underwood, A. (2001). Religion and the brain. Newsweek, 137 (19), 50-58. D’Aquili, E., & Newberg, A. B. (1999). The mystical mind: Probing the biology of religious experience. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. Fontana, D. (2003). Psychology, religion, and spirituality. Malden, MA: BPS Blackwell. Newberg, A., D’Aquili, E., & Rause, V. (2001). Brain science and the biology of belief: Why God won’t go away. New York: Ballantine Books. Peters, K. E. (2001). Neurotheology and evolutionary theology: Reflections on The Mystical Mind. Zygon, 36, 493-500. Rottschaefer, W. A. (1999). The image of God of neurotheology: Reflections of culturally based religious commitments or evolutionarily based neuroscientific theories? Zygon, 34, 57-65. Woodward, K. L. (2001). Faith is more than a feeling. Newsweek, 137 (19), 58. Your Brain 19 References Ashbrook, J. B., & Albright, C. R. (1997). The humanizing brain: Where religion and neuroscience meet. Cleveland: The Pilgrim Press. Begley, S., & Underwood, A. (2001). Religion and the brain. Newsweek, 137 (19), 50-58. D’Aquili, E., & Newberg, A. B. (1999). The mystical mind: Probing the biology of religious experience. Minneapolis: Fortress Press. Fontana, D. (2003). Psychology, religion, and spirituality. Malden, MA: BPS Blackwell. Newberg, A., D’Aquili, E., & Rause, V. (2001). Brain science and the biology of belief: Why God won’t go away. New York: Ballantine Books. Peters, K. E. (2001). Neurotheology and evolutionary theology: Reflections on The Mystical Mind. Zygon, 36, 493-500. Rottschaefer, W. A. (1999). The image of God of neurotheology: Reflections of culturally based religious commitments or evolutionarily based neuroscientific theories? Zygon, 34, 57-65. Woodward, K. L. (2001). Faith is more than a feeling. Newsweek, 137 (19), 58.