TWO MISTAKES ABOUT EPISTEMIC PROPRIETY

advertisement

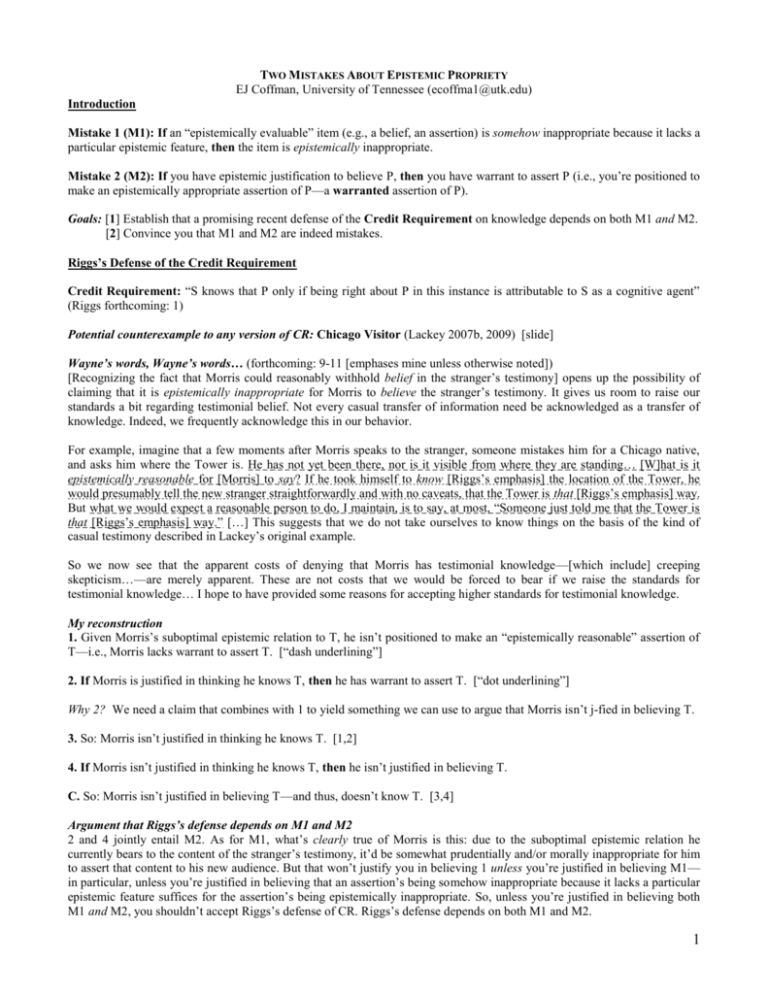

TWO MISTAKES ABOUT EPISTEMIC PROPRIETY EJ Coffman, University of Tennessee (ecoffma1@utk.edu) Introduction Mistake 1 (M1): If an “epistemically evaluable” item (e.g., a belief, an assertion) is somehow inappropriate because it lacks a particular epistemic feature, then the item is epistemically inappropriate. Mistake 2 (M2): If you have epistemic justification to believe P, then you have warrant to assert P (i.e., you’re positioned to make an epistemically appropriate assertion of P—a warranted assertion of P). Goals: [1] Establish that a promising recent defense of the Credit Requirement on knowledge depends on both M1 and M2. [2] Convince you that M1 and M2 are indeed mistakes. Riggs’s Defense of the Credit Requirement Credit Requirement: “S knows that P only if being right about P in this instance is attributable to S as a cognitive agent” (Riggs forthcoming: 1) Potential counterexample to any version of CR: Chicago Visitor (Lackey 2007b, 2009) [slide] Wayne’s words, Wayne’s words… (forthcoming: 9-11 [emphases mine unless otherwise noted]) [Recognizing the fact that Morris could reasonably withhold belief in the stranger’s testimony] opens up the possibility of claiming that it is epistemically inappropriate for Morris to believe the stranger’s testimony. It gives us room to raise our standards a bit regarding testimonial belief. Not every casual transfer of information need be acknowledged as a transfer of knowledge. Indeed, we frequently acknowledge this in our behavior. For example, imagine that a few moments after Morris speaks to the stranger, someone mistakes him for a Chicago native, and asks him where the Tower is. He has not yet been there, nor is it visible from where they are standing… [W]hat is it epistemically reasonable for [Morris] to say? If he took himself to know [Riggs’s emphasis] the location of the Tower, he would presumably tell the new stranger straightforwardly and with no caveats, that the Tower is that [Riggs’s emphasis] way. But what we would expect a reasonable person to do, I maintain, is to say, at most, “Someone just told me that the Tower is that [Riggs’s emphasis] way.” […] This suggests that we do not take ourselves to know things on the basis of the kind of casual testimony described in Lackey’s original example. So we now see that the apparent costs of denying that Morris has testimonial knowledge—[which include] creeping skepticism…—are merely apparent. These are not costs that we would be forced to bear if we raise the standards for testimonial knowledge… I hope to have provided some reasons for accepting higher standards for testimonial knowledge. My reconstruction 1. Given Morris’s suboptimal epistemic relation to T, he isn’t positioned to make an “epistemically reasonable” assertion of T—i.e., Morris lacks warrant to assert T. [“dash underlining”] 2. If Morris is justified in thinking he knows T, then he has warrant to assert T. [“dot underlining”] Why 2? We need a claim that combines with 1 to yield something we can use to argue that Morris isn’t j-fied in believing T. 3. So: Morris isn’t justified in thinking he knows T. [1,2] 4. If Morris isn’t justified in thinking he knows T, then he isn’t justified in believing T. C. So: Morris isn’t justified in believing T—and thus, doesn’t know T. [3,4] Argument that Riggs’s defense depends on M1 and M2 2 and 4 jointly entail M2. As for M1, what’s clearly true of Morris is this: due to the suboptimal epistemic relation he currently bears to the content of the stranger’s testimony, it’d be somewhat prudentially and/or morally inappropriate for him to assert that content to his new audience. But that won’t justify you in believing 1 unless you’re justified in believing M1— in particular, unless you’re justified in believing that an assertion’s being somehow inappropriate because it lacks a particular epistemic feature suffices for the assertion’s being epistemically inappropriate. So, unless you’re justified in believing both M1 and M2, you shouldn’t accept Riggs’s defense of CR. Riggs’s defense depends on both M1 and M2. 1 Against M1 Argument from analogy to other kinds of propriety Moral Analogue of M1 (MAM1): If a “morally evaluable” item is somehow inappropriate because it lacks a particular moral feature, then the item is morally inappropriate. Prudential Analogue of M1 (PAM1): If a “prudentially evaluable” item is somehow inappropriate because it lacks a particular prudential feature, then the item is prudentially inappropriate. 1. Analogues of M1 for other kinds of propriety—in particular, MAM1 and PAM1—are false. 2. Epistemic propriety is in many ways similar to other kinds of propriety—in particular, moral and prudential. C. So M1 is false too. Direct counterexample to M1 You have epistemic justification to believe—but aren’t in a position to know—you won’t recover from your illness. And it’s up to you whether you form this belief. Given your circumstances, it’d be morally/prudentially appropriate for you to form that belief if—but only if—you were positioned to know you won’t recover. You go on to form an epistemically justified belief that you won’t recover. Your belief is morally/prudentially inappropriate because it falls short of knowledge. So, you have an epistemically appropriate belief that’s nevertheless somehow inappropriate because it lacks a certain epistemic feature—being an instance of knowledge. Against M2 1st ground-clearing point Justification to believe and warrant to assert are surely similar in many ways. So if M2 is false, then it’s possible that you bear some but not all of a group of quite similar relations to a given proposition or state of affairs. But this point does not in itself lend even a whit of support to M2: it’s clearly possible that you bear some but not all of a group of quite similar relations to a given proposition or state of affairs. Examples abound; here’s one that doesn’t involve epistemic relations. Unlike some of those who legitimately attend departmental meetings (e.g., student representatives), I have the authority to move that the meeting be adjourned, and also to vote that the meeting be adjourned. Unfortunately, I don’t (yet!) have the authority to adjourn departmental meetings—i.e., to directly bring it about that a departmental meeting is adjourned. So, I have the departmental authority to bear some but not all of a group of similar relations (moving that, voting that, directly bringing it about that) to The departmental meeting is adjourned. If M2 is false, then you could land in the following predicament which is relevantly similar to my “departmental” predicament: though you’re well positioned enough relative to P to justifiedly believe it, you’re not well positioned enough relative to P to warrantedly assert it. 2nd ground-clearing point Elementary reflection on the nature of belief and assertion should (at least) make us wonder whether M2 is true. Things happen when you assert P that don’t happen when you merely believe P. Most obviously, when you make an assertion, you “propel a proposition out into a conversation with assertoric force”. Further, when you assert P, you represent yourself as being in certain cognitive states relative to P—e.g., knowing P and thus believing P. Finally, it’s plausible to think that when you assert P, you (at least typically) commit yourself (somehow) to defending P if an interlocutor subsequently challenges P (cf. the dialectical model of assertion). None of these things happen simply in virtue of your believing P. So: things happen when you assert that don’t happen when you merely believe. It’s thus worth wondering whether being well positioned enough relative to P to justifiedly believe it ensures you’re also well positioned enough relative to P to warrantedly assert it. 1st counterexample to M2: Lottery propositions P is a lottery proposition =df. P “while highly likely, is a proposition that we would be intuitively disinclined to take ourselves to know” (Hawthorne 2004: 5). You have justification to believe some or other lottery proposition, L—e.g., I won’t win the upcoming lottery I hold a ticket in, The letter I just sent overseas will arrive safely, The next flight I take won’t crash, I won’t be in a car accident on my way back to the hotel tonight. But consistent with this, we can add details so that you lack warrant to assert L. Consider: You’re justified in believing the fact that you don’t know L. Further, you’re justified in thinking yourself a reliable source of information. Accordingly, if you were to assert L, the (mis)information that you know L would be conveyed to you by a source you justifiedly reckon reliable (you!). You’d thereby gain evidence that you know L; and this would (at least temporarily) defeat your justification for believing the fact that you don’t know L. Finally, a (plausible!) thesis about warranted assertion: if simply asserting P would defeat justification you now have to believe certain facts about P’s epistemic status for you, then you’re not positioned to make an epistemically non-defective assertion of P. So in the example just constructed, you lack warrant to assert L, even though you have justification to believe L. M2 is false. 2 2nd counterexample to M2: Moorean propositions You could have justification to believe a Moorean Proposition (MP)—i.e., a proposition of the form P & I don’t believe P. Two proposals: while you have justification to believe P, you’re also justified in believing you’re “in denial” vis-à-vis P (cf. Lackey 2007a); or, while you have justification to believe P, you also justifiedly endorse requirements on believing P that are in fact too restrictive. But consistent with this, we can add details so that you lack warrant to assert MP. As before, you’re justified in thinking yourself a reliable source of information. Accordingly, if you were to assert MP, the information that you believe MP’s first conjunct would be conveyed to you by a source you justifiedly reckon reliable (you!)—this happens when you assert MP’s first conjunct. You’d thereby gain evidence against MP’s second conjunct (which, remember, says you don’t believe the first conjunct); and this would (at least temporarily) defeat your justification to believe MP itself. Finally, another (plausible!) thesis about warranted assertion: if simply asserting P would defeat justification you now have to believe P, then you’re not positioned to make an epistemically non-defective assertion of P. So in the example just constructed, you lack warrant to assert MP, even though you have justification to believe MP. M2 is false. Argument from Reliability Requirement (RR) on warranted assertion You can have justification to believe P even if you’re not in fact reliable on the question whether P, even if you can’t in fact be counted on to believe truly with respect to P (think: New Evil Demon Problem for “pure reliabilism”, which enjoys significant uptake on both sides of the “internalism”/“externalism” debate over justification). For example: you can have justification to believe certain “worldly” propositions—e.g., I have hands—even if you’re in fact a massively deceived (handless) BIV. But it’s also plausible that if you can’t be counted on to get it right as to whether P, you’re not positioned to make an epistemically proper assertion of P. That is, it’s plausible that warrant to assert P requires reliability or trustworthiness on the question whether P: warranted assertion requires reliability. So, warrant to assert requires something unnecessary for justification to believe. M2 is therefore false. ▪ The Challenge Argument for RR We have ways of indicating that a person’s assertion on a particular issue was epistemically defective. One way is to ask a question or make a statement concerning the person’s reliability or trustworthiness on that issue. Examples of such questions and statements include: “Is he reliable on this issue?”, “Can we count on her to be right about this?”, and “He doesn’t know what he’s talking about.” So, a question or statement about one’s (lack of) reliability relative to P can generate evidence that one lacks warrant to assert P. A natural explanation of the fact that evidence of unreliability counts as evidence of lacking warrant to assert is that unreliability on P entails lack of warrant to assert P. So, the fact that you can indicate that an assertion was epistemically defective by indicating that its agent was unreliable on its content is good (albeit defeasible) evidence for RR. ▪ The Apology Argument for RR If you make an assertion but then learn that you were in fact untrustworthy on its content, you could sensibly apologize for making that assertion (though perhaps you aren’t required to do so). The fact that you could sensibly apologize for your assertion (as opposed to, e.g., simply regretting that you made it, or apologizing for its consequences) upon learning of your unreliability indicates that your unreliability made the assertion itself somehow inappropriate. Now, while there surely are cases where your unreliability on P renders your assertion of P morally and/or prudentially inappropriate, this won’t always be the case. Plausibly, then, the kind of impropriety had by any assertion whose agent is unreliable on its content is epistemic impropriety: you’re positioned to make an epistemically proper assertion of P only if you’re reliable on P. So, the fact that you can always sensibly apologize for making an assertion on whose content you were unreliable is good (albeit defeasible) evidence for RR. 3 References Adler, Jonathan E. 2002. Belief's Own Ethics. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Bergmann, Michael. 2004. “Epistemic Circularity: Malignant and Benign.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 69: 709-27. Bird, Alexander. 2007. “Justified Judging.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 74: 81-110. Black, Max. 1952. “Saying and Disbelieving.” Analysis 13: 25-32. Brandom, Robert. 1983. “Asserting.” Nous 17: 637-50. ———. 1994. Making It Explicit. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Brown, Jessica. 2008. “The Knowledge Norm for Assertion.” Philosophical Issues 18: 89-103. ———. Forthcoming. “Knowledge and Assertion.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. DeRose, Keith. 1991. “Epistemic Possibilities.” Philosophical Review 100: 581-605. ———. 1996. “Knowledge, Assertion and Lotteries.” Australasian Journal of Philosophy 74: 568-79. ———. 2002. “Assertion, Knowledge, and Context.” Philosophical Review 111: 167-203. Douven, Igor. 2006. “Assertion, Knowledge, and Rational Credibility.” Philosophical Review 115: 449-85. Dummett, Michael. 1981. The Interpretation of Frege's Philosophy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Green, Mitchell and John Williams. “Introduction.” In M. Green and J. Williams (eds.), Moore’s Paradox. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Greco, John. 2003. “Knowledge as Credit for True Belief.” In M. DePaul and L. Zagzebski (eds.), Intellectual Virtue: Perspectives from Ethics and Epistemology. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ———. 2007. “The Nature of Ability and the Purpose of Knowledge.” Philosophical Issues 17: 57–69. Hawthorne, John. 2004. Knowledge and Lotteries. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Kvanvig, Jonathan. 2003. The Value of Knowledge and the Pursuit of Understanding. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ———. Forthcoming-a. “Assertion, Knowledge, and Lotteries.” In D. Pritchard and P. Greenough (eds.), Williamson on Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ———. Forthcoming-b. “Responses to Critics.” In A. Haddock, A. Millar, and D. Pritchard (eds.), The Value of Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lackey, Jennifer. 2007a. “Norms of Assertion.” Nous 41: 594-626. ———. 2007b. “Why We Don't Deserve Credit for Everything We Know.” Synthese 158: 345-61. ______. 2009. “Knowledge and Credit.” Philosophical Studies 142: 127-42. Levin, Janet. (2008) “Assertion, Practical Reason, and Pragmatic Theories of Knowledge.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 76: 359-84. Moore, George Edward. 1963. Commonplace Book, 1919-1953. London: Allen & Unwin. Peirce, C.S. 1934. “Belief and Judgment.” In C. Hartshorne and P. Weiss (eds.), Collected Papers, Vol. V. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press. Pritchard, Duncan. 2005. Epistemic Luck. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Pryor, James. 2005. “There is Immediate Justification.” In M.Steup and E. Sosa, Contemporary Debates in Epistemology. Malden, MA: Blackwell. Rescorla, Michael. Forthcoming. “Assertion and its Constitutive Norms.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. Reynolds, Steven L. 2002. “Testimony, Knowledge, and Epistemic Goals.” Philosophical Studies 110: 139-61. Riggs, Wayne D. 2007. “Why Epistemologists Are So Down on Their Luck.” Synthese 158: 329-44. ———. Forthcoming. “Two Problems of Easy Credit.” Synthese. Slote, Michael. 1979. “Assertion and Belief.” In J. Dancy (ed.), Papers on Language and Logic. Keele: Keele University Library. Sosa, Ernest. 2007. A Virtue Epistemology: Apt Belief and Reflective Knowledge. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Sutton, Jonathan. 2005. “Stick to What You Know.” Nous 39: 359-96. ———. 2007. Without Justification. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press. Unger, Peter. 1975. Ignorance: A Case for Scepticism. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Vogel, Jonathan. 1990. “Are There Counterexamples to the Closure Principle?” In M. Roth and G. Ross (eds.), Doubting: Contemporary Perspectives on Skepticism. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers. Watson, Gary. 2004. “Asserting and Promising.” Philosophical Studies 117: 57-77. Weiner, Matthew. 2005. “Must We Know What We Say?” Philosophical Review 114: 227-51. Williamson, Timothy. 2000. Knowledge and Its Limits. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Wright, Crispin. 1996. “Response to Commentators.” Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 56: 911-41. Zagzebski, Linda. 1996. Virtues of the Mind: An Inquiry into the Nature of Virtue and the Ethical Foundations of Knowledge. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 4