proposal guidelines SSHRC

advertisement

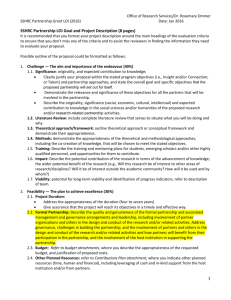

Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 1 Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Standard Research Grant Proposals Philip H. Winne Professor and Research Coordinator Faculty of Education Simon Fraser University Criteria Used in Judging a Proposal 1. Originality and Contribution to Knowledge A program = multiple but separable investigations articulated under a theme. Explain your theme and show clearly how it links to other themes in the field (e.g., cite and briefly discuss major books, theoretical review articles). Identify the theme’s roots, especially in your own prior work. Project your theme’s future following the 3 year period for which your are now applying. Originality. Demonstrate knowledge of what has been done in general (e.g., cite major reviews) and of relevant particulars (specific investigations). Analyze specific prior work, including your own1, for gaps or miscues in underlying premises, opportunities forgone to collect specific types of data, types of analyses not done, or needs for modest extension and replication. A vital program of research is reflective and corrective. Contribution. Cite “calls for more research” made in prominent papers of your field and show how your work responds to them. Don’t be modest—write in the first person: “In my prior work on this issue (Myself, 1993), I found that X and Y. These results undermine/ complement/clarify a significant issue revealed in Eminent and Prominent’s (1993) research, that of … .” 2. Suitability of Theoretical Approach “Suitability” does not convey the notion of what is sought here. Assessors and SSHRC’s Committee’s are concerned about the extent to which you (a)have a theory/framework, (b) use or challenge it in your work, and (c) improve the theory/framework by conducting your investigation(s). Two main functions of a theory or conceptual framework are to (a) reveal otherwise implicit elements in a system and (b) explain phenomena. Use clear terms (e.g., pointform, diagram) and present a theoretical/conceptual framework to explain what is the “state of the field”. Specify how your program of research is relevant to examining and extending that theory/framework, and show clearly how each study or component of your 3-year proposal addresses a specific feature of that theory/framework. Give some Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 2 indication about how the theory/framework will change as a result of your work. Alternatively, what question(s) about the theory/framework does your work answer? 3. Appropriateness of research strategy, methodology Avoid unnecessarily technical terms. It won’t impress, and it might frustrate an assessor. Explain the method and show how it addresses the theory/being investigated. For example: Poor: “An interview will be conducted with each participating teacher.” Better: “The model of classroom environment proposed by Fraser (1991) and supplemented by me (Myself, 1993) will be examined in a 3-phase interview. (1) The interviewer and teacher will watch a video of the previous week’s lessons prepared (edited by RAs and me) to show contrasts of student behavior related to the typology outlined in Table 1 (above). Upon conclusion, the interviewer will invite open-ended descriptions about main issues that concern the teacher about classroom environment. (2) For each issue, dimensions proposed by Midgley et al. (1991) will be probed explicitly and the teacher asked to comment. (3) Any topics in Moos’ (1991) framework not introduced by the teacher’s elaborations in part 2 then will be described, and the cycle in (2) repeated. Sessions will be audiotaped …” If there are a series of studies or investigations that use different methods, select one or two as illustrative. The purpose is to demonstrate expertise in (a) methodology per se as well as (b) how to link methodology with the theory/framework that guides your program of research. Diversity of methodology (multidisciplinarity) is an asset if weaknesses of one approach are compensated by strengths of another when addressing the same or very closely aligned topic. Merely listing diverse methods can convey a lack of clarity about what is addressed in your work. Keep methodological description at a “medium-general” level. Too many specifics sometimes invites overly specific and unnecessary criticisms. Describe directions you methods will take (e.g., “appropriate multivariate techniques such as path analysis” or “passes through the text at levels corresponding to individual and group perspectives”) but leave out details. The idea is to guide assessors to fill in the details (because they are experts) and that the assessors recognize as a sophisticated and appropriate methodological approach to your research.. 4. Suitability & effectiveness of plans for dissemination Do not neglect this issue. Consider and present a plan for dissemination that is appropriate for the scholarly community and for the wider professional or lay audience. Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 3 Workshops, working groups involving key players in schools, newsletters for professionals, and symposia at professional meetings are venues to consider beyond the usual travel to scholarly conferences. Section by Section Notes Summary Articulate the summary with the body of the proposal to help readers understand your work. Create a 1-1 mapping between the two sections. a. Avoid technical terms and phrases. b. Omit citations. Don’t repeat verbatim in the full proposal what you write here. Use all allowed space to communicate information. Ask a colleague outside your field to read and critique the Summary. Does your colleague understand what you are trying to describe? Proposal (6 pp.) Topics to address: • • • • • general objectives theoretical perspective how your research advances the scholarly field nature of research strategies/methodological approaches relationship to your ongoing research, your career-long research program • relationship to budget In general: a. Avoid technical terms and phrasing where possible. If you must use a technical term repeatedly, define the term or elaborate the phrase where it is first used. Make this exceptionally clear. b. Elaborate briefly information that a citation conveys. A particular external assessor and SSHRC Panel members may not be acquainted with luminaries in your field and, hence, may not grasp the significance of a citation. For example, “Famous (1994) addressed issues in evaluating applications of advanced computing technologies in education. A main point of his analysis was that a complete evaluation must address more than merely the effect of a computing system on achievement.” c. Avoid long lists of citations as evidence for your knowledge of the field. Expertise is better conveyed by clear presentation of vital ideas rather than extensive bibliographies. Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 4 d. Don’t be overly modest in citing your own work, but show how it links to and adds to others’ work in the field. e. Define work that reasonably can be done in a 3-year period and that links to both prior and future issues in your field. f. Describe your long-term program of research in three parts: (1) what the program is and what’s been accomplished in the last 3-5 years, (2) what’s underway presently and continuing between the date of submission (15 Oct.) and late spring (March) when SSHRC adjudicates proposals, and (3) what will be done in the 3 years for which you are funded. A very flexible guideline for proportion among these sections might be 1:1:4. g. SSHRC funds theoretical and basic research. While practical applications or applied research should be briefly noted as outgrowths of your program of research, scholarly/theoretical questions should be define a hub from which applications are arrayed on the rim of your proposal. h. Demonstrate the educational relevance of your program of research. What important educational question or issue is addressed? Description of Team A team is an asset to the extent that (a) team members complement one another and (b) there is synergy. Describe explicitly how team members work solo and in concert. What does each do and how do these efforts articulate to produce a fuller, deeper scholarly work? Do not “team” with a top person in your field hoping to benefit from a halo effect. This implies you haven’t resources or wherewithal to complete the research yourself. Training (Role of Students) SSHRC says: [Adjudication committees] expressed concern about whether the activities earmarked for students are providing them with real opportunities for intellectual involvement and enrichment. … research proposals which request funds for student research assistants must clearly describe the particular role and responsibilities which these students will have in the research program. Describe how research activities assigned to RAs extend topics in courses they study. For example, “Developing coding schemes for the interviews and addressing issues of reliability in coding substantially extends topics studied in their courses on research Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 5 methods.” Or, “Preparation of materials and activities for the in-service workshop, in which student teachers will be instructed about teaching method X, builds directly on studies that RAs have been pursing in seminars on organizational development.” Indicate explicitly your role in guiding and collaborating with RAs in substantial research tasks. For instance, “The RAs and I will interview students, then collaborate in analyzing the protocols to explore the links so-and-so (19xx) noted as the next step needed in this area.” Or, “In conducting the meta-analysis of the evaluation studies in this area, I will select the studies and then advise the RAs in analyzing, writing, and presenting their results at the AERA meetings our results.” In the 6 pp. description of research, cite publications, conference papers, and research reports which you have co-authored with graduate students and use phrasing that identifies these as such. For example: “In collaboration with my graduate assistants (Myself, RA1, & RA2, 1992), we conducted experiments that showed … ”. Or, “A platform for this hypothesis was built in my graduate student’s master’s thesis (Masterstudent, 1989) …” Describe how research activities assigned to RAs extends topics in courses they take. For example, “Developing coding schemes for the interviews and addressing issues of reliability in coding substantially extends their knowledge of major topics studied in their courses on research methods.” Or, “Preparation of materials and activities for the inservice workshop, in which student teachers will be instructed about teaching method X, builds directly on studies the RAs have been pursing in seminars on organizational development.” Research Contributions Entries: books, book chapters, articles, reviews of work, “other contributions” (conference presentations if refereed and significant), popularization for the general public. A few works “under review” by a journal or accepted for presentation at major conferences can convey a sense of activity, but too many will appear as padding and suggest a excessive position of “hopefulness” about progress in your program of research. List works “in progress” especially sparingly—works in progress are clear indicators of vital a program of research, so they don’t discriminate your track record from others’. Activity in this regard is better conveyed in sections on Training Future Scholars and Results from Recent Grants, and by descriptions of prior elements of your research program in the body of the proposal. Annotate an entry if it’s helpful to an assessor. Differentiate scholarly from professional entries. Don’t “misrepresent” non-refereed entries as refereed as this can invite questions about your representation of other entries’ classifications or about your grasp of what scholarship “means.” Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 6 Other Contributions to Research List journal editorial boards, journals reviewed for ad hoc, conference program committees, grants reviewing, service to scholarly associations that reflects your scholarly expertise. Training Future Scholars Cite any items co-authored with students or your students’ publications not in the Research Contributions. Name any students you supervised or worked with who have gone on to scholarly careers. Note awards won by students you supervised. Describe how, in prior research, students gained knowledge and skill that they used in completing their thesis. Exceptional Circumstances Affecting Record of Research Identify specific causes but note them only if they (a) genuinely interfere, and (b) were unforseeable or (c) uncontrollable. Do not cite minor interferences or events which, though delaying, were due to poor planning or predictable problems. Administrative responsibilities likely will be judged as reducing your opportunity to pursue research but not as acceptable justification for zero output. Results from Recent Grants If you have several funded programs of research in addition to that described in the main proposal, present those accomplishments here. Describe accomplishments arising from applied/action research or contributions to professional development that clearly grow out of prior activities in your program of research. Explicitly address how these results relate to your current application. Budget Justification Personnel. Balance activities between you and staff. Describe and justify your role(s) in and contribution(s) to research activities. Why can’t you do it all? “Task-out” aspects of the work. For example: “An average interview involves: 15 min to set an appointment, 45 min transit, 90 min to conduct. Coding, computer entry, and reliability checking take approximately 2.5 times the interview length, 225 min. Total estimated time for 50 interviews = 6.25 hr/interview x 50 ≈ 315 hrs. of RA time. Transcription time is approximately double the length of the interview, 2 x 90 min. x 50 interviews ≈ 150 hrs.” Include training time for RAs, clerical staff. Include project management costs (e.g., organizing data for storage). If space in the proposal is tight, use space here to describe tasks in a manner that shows how students can gain useful training. Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 7 Transportation and Subsistence. Use university rates ($/km for car, per diem). Otherwise, identify source of quote and date, e.g., “Air Canada quote, Sept. ‘96: Vancouver-London return $799 + tax = $874.” Professional/technical services/contracts. Use university rates or identify source of quote and date (e.g., duplicating, transcription, software programming). Include benefits and relevant taxes. Heed SSHRC regulations that researchers “are expected to have the full qualifications and experience necessary to carry out research … ” Computer hardware/software. Identify source of quote and date. Explicitly describe why extant resources within your department are unavailable for your use or inadequate. E.g., “Computers in our Technology Centre can not be reserved. Mounting my personally licensed word processor on the Lab’s network will violate the software license agreement, so my RAs need their own computer and word processing software.” Hardware is a disputed item as to whether it is infrastructure that the university is supposed to supply or genuine research-related equipment. Craft your argument clearly showing why a computer is essential to the research. Don’t rest on a claim that, “My university can not afford to buy me a computer.” Non-disposable equipment and supplies. General wording (e.g., transcription unit; paper, notebooks) will do unless this is a big chunk of money, say, $500/yr or more. If equipment, specify make & model. Justify. Justify computer upgrades by identifying features that are necessary (e.g., video card for editing classroom observations). Non-disposable equipment. Identify source of quote and date. Explicitly describe why extant resources within your department are unavailable for your use or inadequate. Include archiving costs (e.g., backup of data on computer media). Communication of results. Identify source of quote and date. Name specific scholarly meetings, including dates and locations, and justify why they are appropriate audiences. E.g., “In the last 3 years, the American Educational Research Association’s conference has averaged 22 sessions on topic X.” Workshops for scholarly peers is a productive venue for communicating results of and gaining input for your research. General. Once a grant is received, you have full control over your budget. You can shift money across categories because SSHRC assumes you in the best position to adapt to unfolding events. Check whether your university will “stake” you to a portion of next fiscal year’s funds should you overspend in a given fiscal year. Unspent funds may be carried over fiscal years within a 3-year period (from year 1 to 2, year 2 to 3) but not across grants. Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca Guidelines for Preparing SSHRC Proposals P. H. Winne 8 Research Time Stipend There have been so few of these awarded in recent years that, statistically, it is practically guaranteed that these requests will fail. If you believe you must apply, your argument must be forceful. Alternatively, ask for more funds to support research staff, e.g., a post-doctoral student who has adequate preparation to do the work. Suggested Reviewers a. Nominate reviewers who will write objective, substantive reviews. Cheerleaders or raving supporters add nothing, and may detract from your profile. b. Coordinate what you cite and how you use citations vis à vis reviewers you nominate. c. Don’t hesitate to nominate non-Canadians. d. Provide a full and current address for each nomination. Check addresses with the reviewers you nominate. e. Do not nominate assessors not at arm’s length (e.g., co-authors, dissertation supervisors). It is proper to seek scholarly critiques of your work, well prior to filing your SSHRC proposal, then nominate those whom you consulted as possible reviewers. Develop a network of scholars. Research Coordinator in Education Faculty of Education, Simon Fraser University Burnaby, BC V5A 1S6 Telephone Fax E-mail (Internet) 604-291-4858 604-291-3203 winne@sfu.ca