Bridging Design and Manufacturing: Improving

advertisement

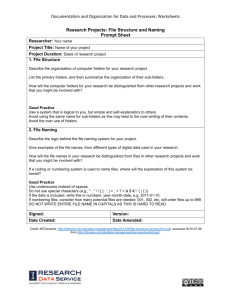

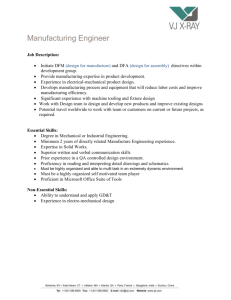

1205EF2-StonePillar.doc Keywords: data management system, Design-for-Manufacturability, threshold voltage Editorial Features Tab: Method-Tools ---- DFM Aids ESL Designs @head:Bridge the Gap between Design and Manufacturing @deck:The disconnect between manufacturing and design activities can be improved with a cross-disciplinary data-management system. @text:The aim of design for manufacturability (DFM) is to optimize both semiconductor manufacturing processes and the design itself. Yet the decisions about how to optimize a technology are growing increasingly complex. In addition, they involve the simultaneous consideration of design issues and process parameters. These simultaneous considerations demand visibility that spans design rules and design-rule intent as well as the impact of process parameters on device performance and yield. At present, this sort of collaborative effort is unsupported by the tools that are needed to optimally share information. Because few engineers have detailed knowledge of both the design and the manufacturing disciplines, linking the process data back to physical design also is becoming a stumbling block. A data-management system that allows engineers to analyze both process parameters and design rules will provide one means for bridging these disparate disciplines. Visibility Optimizes DFM As geometries shrink and product life cycles shorten, the yield ramp becomes increasingly important as a determinant of product profitability. Speeding this ramp and maintaining yield with minimal additional engineering effort can be critical to meeting a market window and making a profit. To support effective decision making, engineers must bring together data from the disparate disciplines of process optimization and design optimization in a way that supports meaningful insights. Before changing a design rule, for instance, it’s important to ask if the same effect can be achieved through a change in one or more process parameters or steps in a process flow. Only by exploring both design and process parameters simultaneously can a true “optimum” yield/performance point be found. In a typical implementation, the details of the process flow are maintained in a manufacturing database that is, at best, partially linked to device-design details. Because device-design and manufacturing detail reside in more than one place, optimization considerations are split between departments. The optimization of process technology is often considered separately from the optimization of design rules. Or it is addressed by different persons or groups within a technology-development organization. In the event that a combined analysis is attempted, it typically involves time-consuming, error-prone data assembly that diminishes the desirability and reliability of the conclusions. By optimizing cross-disciplinary data sharing and analysis, engineers in both areas gain valuable insight into DFM issues from early-stage technology development through yield improvement. A complete data-management system for technology development makes it easy to track variations in functionality back to their causes. It also provides the data to create high-yield designs while allowing the reuse of valuable information for future iterations or products. This centralized and shared information is the best available source for details of how product performance will respond to process and geometric variations. It also provides a basis for informed decision making in yield-improvement stages downstream. Improving Visibility One approach to improving the visibility of information about the impact of process and design variables is illustrated in Figure 1. This graphic represents a data-management system that interconnects downstream electrical test data (and reports that include this data) with the key aspects of processing that produced the test results. For instance, this system enables the easy navigation from a particular electrical test result to the test structure layout, process flow, experiment, design rules, and other aspects of fabrication. Such aspects might be under consideration for improving the yield or performance of a product or process. In practice, the flow of information in such a system might work as follows: In the early stage of technology development, preliminary targets are established to develop a new process. These targets include a set of test devices, parameters to be measured for these devices, and device support levels. The key devices in the technology, for example, will typically include targeted performance metrics and SPICE model support for delivery to the design organization. In addition, certain devices may not be targeted for use in design but will provide useful information about technology performance. They also will have a reduced support level. These device-performance targets may include various limits, such as scrap or disposition limits. But initially, they’re more likely to include only desired performance targets and support levels. These targets and levels will be refined as the technology develops and realistic performance expectations begin to shape up. Imagine that all of this information is stored in the datamanagement system in a way that allows easy perusal by interested stakeholders in the technology-development process. Revisions and their impact will thus become easier as understanding of the process improves. Once the desired devices have been determined, the creation of initial test structures begins. Ideally, the test structures have a direct relationship to the target devices from the previous step. They are linked to the corresponding targets by the data-management system. A crossdisciplinary data-management solution also would enable the easy revision of individual devices or a complete test chip as design rules or critical device dimensions shift. In addition to any geometric splits that are included in the test chip, the early stage of technology development is likely to include exploratory process splits. Such splits are used to seek out an optimum tradeoff solution in the processing space. The experimental splits also should be established in the data-management system. After the test-chip layout has been created and sent for fabrication, it’s time to build a test plan that corresponds to the desired measurements. A significant advantage accrues from the proper use of the data-management system up to this point. In a complete technology-development datamanagement system, the full details of the test chip and target parameters can be used to automate the creation of the test plan. For instance, the pad locations and terminals for each device (established by the test-chip creation) are already present in the data-management system. As a result, applying tests to individual devices can be done without plunging into the details of their location and connection within the test chip. Existing algorithm libraries also can be applied to the test chip through capabilities provided by the data-management system. Once sample wafers have been created, this test plan can be run against them. The data produced from running the test plan can automatically be linked to the specific device designs included in the test chip and corresponding targets. The data from the test results becomes the basis for various reports and interactive review (see Figure 2). These reports and review methods illustrate how a data-management system, such as the one previously described, can be used to peruse the full details of a test device that either fails or produces desired behavior. The cause of failure can be determined by perusing the processing details that produced the failed device. Examples include device layout, test algorithm, experimental split, or design rules. Another advantage of a cross-discipline data-management system is more effective process monitoring (see Figure 3). Reports can be generated automatically to superimpose information about device targets, device dimensions, and test results. One can easily determine trends in process drift and take corrective action if they are nearing the limits imposed on the process. In addition, the retention of details about processing splits and their effect on device performance provides valuable details that can be used to improve yield in the event of process drift or process-improvement efforts downstream in production. As an example of the simultaneous review of process and design parameters, consider a hypothetical case involving the review of a process and design parameter (see Figure 4). Here, achieving a desired value for a key device metric--in this case threshold voltage (VTX)--can be realized through either of two approaches. Threshold voltage responds to changes in a design rule (variations of which are plotted along the horizontal axis). It also responds to the variations in a process parameter, which are shown by the color grouping of the data. Such a view helps to pinpoint which of these two variables is most advantageous in changing or improving the threshold-voltage value. It’s likely that the answer to this question will lead to numerous other questions. An example is the impact of the possible changes on other device-performance metrics, such as leakage or saturation currents. Sensitivity to process variations or random defects also could be influenced. Within the framework of the described data-management approach, these issues can be readily explored as part of the input to a final decision. DFM challenges for the coming technology nodes are immense. The disconnect between manufacturing and design often comes down to an inability to easily access the same information within a timeframe that’s useful for discussion and analysis. To truly optimize design for manufacturability, engineers must be able to analyze both process and design parameters on equal footing. Tim Crandle, PhD, is President of Stone Pillar Technologies. Crandle has been developing and writing about semiconductor-technology CAD for nearly 20 years. Prior to joining Stone Pillar, he was President of Telelogic North America Inc., a subsidiary of Swedish softwaredevelopment and test-tools vendor Telelogic AB. Dr. Crandle also has managed tool development, product direction, and planning at Silvaco’s Technology Division, Technology Modeling Associates, and MCC. He holds BS, MS, and PhD degrees in Electrical Engineering from the University of Michigan. ++++++++++++ Captions: Figure 1: To improve information visibility, it’s possible to use a common data-management system that interconnects all design and test data. Figure 2: Using the data-management system, the test results can be presented in whatever manner is most appropriate. Figure 3: Process-monitoring reports like the one shown here can be used to superimpose information about device targets, dimensions, and test results. Figure 4: The simultaneous review of process and design parameters on a desired device metric, such as threshold voltage, leads to a balanced tradeoff decision.