Interpreting The Irish Famine, 1846-1850

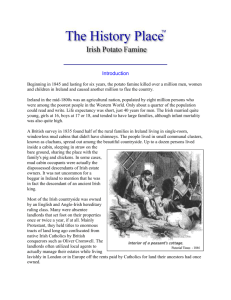

advertisement

H07 - 26 The Irish Potato Famine 2/16/2016 Name: _______________________________________________________ DUE: WED. 13 FEB 2013 Homework: The Irish Potato Famine Global History II THE IRISH POTATO FAMINE 1840s - Potato Famine hits Ireland - 1 million die - 1 million emigrate (leave for the United States) - English landlords still continue to sell Irish grain 1921 - Ireland (southern portion of island) granted its independence - autonomy, sovereignty, home rule - Roman Catholic majority - northern Ireland (Ulster) remains part of England, Great Britain: United Kingdom - Protestant majority Irish Potato Famine Since the reign of Henry VIII, English rulers encouraged Protestant settlement in Ireland from Scotland and England. Eventually the Protestants gained control and passed harsh laws that limited the rights of the Irish Catholic majority. Even though the British eventually gave Ireland representation in Parliament and allowed Catholics to hold political office again, the Irish were still angry. They resented paying taxes to the Anglican Church and high rents to Protestant landlords. PAGE 1 H07 - 26 The Irish Potato Famine 2/16/2016 The Potato Comes to Ireland. Many countries in Europe paid very little attention to the arrival of the potato from the New World. This is because most countries already grew enough food to feed their population, and so there was no reason to grow a new vegetable in large numbers. However, the situation was different in Ireland. During the 1500's Ireland was torn apart by constant warfare between the country’s English rulers and Irish inhabitants, and between local nobles who were always fighting one another. As a result of this continual conflict, Ireland's peasant farmers had a hard time growing enough food to feed themselves, let alone anyone else. It was into this starving, war-torn Ireland that the potato was introduced around the year 1600. The "white" potato, know today as the Irish potato, originated in the Andean Mountains. In 1532 the Spanish arrived in north Peru and it is speculated that they brought the potato to Europe in the second half of the 16th century. No one is sure exactly who introduced the potato to Ireland. Some believe it was the famous English explorer, sea captain and poet, Walter Raleigh. Others speculate that the potato washed up on the beaches of Ireland as part of the shipwreck of the Spanish Armada, which had sunk off the Irish coast in a violent storm. However it arrived, one thing can be said for certain - the potato caught on very quickly in Ireland. The potato's popularity was based on the potato producing more food per acre than any other crops Irish farmers had grown before. In peaceful times the potato spread throughout Ireland as a healthy and reliable source of food. In times of war it was popular as well. When soldiers destroyed farmers' crops and livestock - as soldiers often did -, the potato would survive because it was hidden, buried below ground. When the soldiers left, people could still dig up potatoes and eat them. English colonization of Ireland forced the Irish to pay exorbitant rents and taxes, to export their crops, and to increase their dependence on the potato crop. During the end of the eighteenth century and into the nineteenth century, Ireland experienced rapid population growth, which strained the economy, and left many peasants in subsistence living conditions. With the end of the Napoleonic Wars in 1815, the British soldiers returned home, which increased unemployment. Further, as Europe transitioned from warfare to a time of peace, a depression began and the Irish economy began to falter. At this time, British turned its attention from the European Continent and refocused their attention to their colonial holdings. The primary economic goal of British colonialization was to extract the greatest amount of resources and exports from their colonial holdings to the benefit of the British land-owners. With the colonialization, a tenure system was introduced into Ireland that gave Protestant landlords control of 95% of the land. Every cottage had a garden equal to an acre and a half and the farmland amounted to five acres. As the population grew, the holdings were subdivided and living standards declined. To counter overpopulation, people moved to less fertile areas were the potato was one of the few sources of food that could be grown. Most of these lands were under the ownership of absentee landlords, who wanted to maximize the output with little or no investment into the population. The British instituted Penal laws, which denied the Irish peasant population freedom. Irish were forbidden: to speak their language, to practice their faith, to attend school, to hold an public office, to hold certain jobs, to own land, or to ". . .own a horse worth more than $10." These Penal laws were enacted to push the Irish into submission by force and inferiority and were justified by the British government as necessary to retain the character of the Irish. "From 1816 onward, wet weather destroyed crops, the potato failed in several provinces and, weakened by hunger more than 100, 000 Irish died of starvation and disease." According to one farmer, in late September of 1845 a "wierd mist came over the Irish Sea. . .and the potato stalks turned black as soot." The next day, the potatoes were "a wide waste of putrefaction giving off an offensive odor that could be smelled for miles." The potato blight (photophthora infestans), which caused the Great Famine of Ireland, results from an "airborne PAGE 2 H07 - 26 The Irish Potato Famine 2/16/2016 pathogen" that spreads rapidly among crops "during precise weather conditions." The disease attacks not only the crops in the field, but the crops in storage during this mild and damp period. In 1845, the potato blight destroyed 40% of the Irish potatoes and the following year, approximately 100% of the crop was ruined. Successive crop failure led to "Black '47," with increases in famine, emigration, and disease. Although the potato crops from 1847-1851 were unaffected by the blight, famine conditions intensified due to a lack of seed potatoes for planting new crops and an inadequate amount of potatoes having been planted for fear that the blight would persist. Tenant farmers held short-term leases that were payable each six months in arrears. If the tenants failed to pay their rent, they were jailed or evicted and their homes burned. During the time of the Great Hunger (18451847), approximately 500,000 people were evicted, many of whom died of starvation or disease or relocated to mismanaged and inadequate poor houses. The alternative to eviction, poorhouses, or starvation was emigration, which pre-dated the Potato famine, but rose to over two million people from 1845-1855. In 1851, the largest number of emigrants, a quarter of a million people, left for overseas destinations. The emigration continued through the 1850s and into the 1860s, with an average of an eighth of a million people. Emigrants tended to follow along family routes, which were found mostly in Great Britain, United States, Canada, New Zealand, and Australia. The British were reluctant to provide relief to the inferior people of Ireland. In the 1840s, laissez-faire (leave it alone) philosophy dominated the British economic policy. The government officials supported a policy of non-intervention, which maintained the belief that it was counterproductive to interfere in economics. The chief instrument of relief came in the form of low-paid work projects to build an infrastructure to promote industrialization and modernize the Ireland. Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel repealed the Corn Laws, a protective tariff enabling the Irish to import grain from North America. For this relief measure, Peele was ousted and replaced by Lord John Russell, who was less lenient on the Irish. Relief measures, such as corn importation, were sent from North America; however, these shipments were mere tokens to the necessary relief required to comfort the starving. Charles Trevelyan, Assistant Secretary to the Treasury under the Prime Minister Lord John Russell, oversaw famine relief efforts. In 1846 Trevelyan wrote: "'The problem of Ireland being altogether beyond the power of man, the cure has been applied by all-wise Providence...'" Various relief schemes were tried and abandoned: public works projects, importing corn from America, soup kitchens, workhouses, even sending agricultural advisors to the west of Ireland where they found no surviving farmers. Ultimately, the Russell government ". . .was not prepared to allocate what was needed to head off starvation, but was always ready to dispatch police and troops of dragoons to help a landlord evict destitute tenants or protect a shipment of cattle or grain export." To limit the number of people seeking relief and the expense to the British government, The Poor Law Extension Act of 1847 was instituted to deny aid to tenant farmers with over a quarter acre of land. This Act promoted emigration, increased land clearance, and disintegrated the structure of rural society, which were beneficial to British landowners, who sought profit, power, and larger plots of land. According to the Poor Laws, landlords were bound to support peasants sent to the workhouse, which cost $12 pounds a year. Instead, some landlords sent peasants to Canada on "coffin ships", which cost $6 pounds. Coffin ships were "wet, leaky holds" of timber ships returning to North America that were "crammed in with as many as 900 [people], with barely room to stand."Approximately half of the people died during the voyage and the other half arrived in North America unable to disembark, without assistance, due to sickness and starvation. Ireland was the first country in Europe where the potato became a major food source. By the 1800's, the potato was so important in Ireland that some of the poorer parts of the country relied entirely on the potato for food. PAGE 3 H07 - 26 The Irish Potato Famine 2/16/2016 Because the potato was so abundant and could feed so many people, it allowed the population of Ireland to grow very quickly. By 1840, the country’s population had swelled--from less than three million in the early 1500's to a staggering eight million people--largely thanks to the potato. Some men and women tried to warn everyone that it was dangerous for so many people in one place to be dependent on just one crop. (This is what's known as "one crop economy". Unfortunately, no one listened to their warnings. The blight appeared in Ireland in 1845. The blight was the fungus Phytophthora infestans which destroyed potato plants and was the principal cause of what came to be known as the Irish Potato Famine. The blight wiped out the potato crop in 1845, 1846 and again in 1848. People were left with nothing to eat and no way to make money to support themselves. Many wandered the countryside, begging for food or work. Others ate grass and weeds to survive. Those who could afford to, left the country in search of a better life. Throughout the Potato Famine, from 1845 to 1947, more than one million people died of starvation or emigrated. Additionally, over 50,000 people died of diseases: typhus, scurvy, dysentery. Despite the famine conditions, taxes, rents, and food exports were collected in excess of £6 million and sent to British landlords. Within a decade, the population of Ireland plummeted from over eight million to less than six million. In an attempt to flee the oppression, starvation, and disease that gripped Ireland, the Irish people became the country's greatest export. Although the blight infected crops in the United States, Southern Canada and Western Europe in the years of 1845-1846, the overpopulated subsistence farmers of Ireland were forced to export corn, wheat, barley, and oats to Britain, which left the potato as the sole dietary staple for the people and their animals. While other regions were able to turn to alternative food sources, the Irish were dependent on the potato and the results of the blight were disastrous. Over the course of the famine almost one million people died from starvation or disease. Another one million left Ireland, mostly for Canada and America. Of those who left, many died on board the boats they were travelling in because the conditions were so crowded and dirty. For this reason, the ships that carried Irish immigrants to the New World became known as "coffin ships". Unfortunately immigrants to the New World soon found out that the blight was ravaging potato crops there as well. The combined forces of famine, disease and emigration depopulated the island; Ireland's population dropped from 8 million before the Famine to 5 million years after. If Irish nationalism was dormant for the first half of the nineteenth-century, the Famine convinced Irish citizens and Irish-Americans of the urgent need for political change. The Famine also changed centuries-old agricultural practices, hastening the end of the division of family estates into tiny lots capable of sustaining life only with a potato crop. One hundred and fifty years after the famine, the results are evident in the number of Irish descendants scattered around the globe, the treeless landscape, and the shells of homes that were rendered uninhabitable after the landlords evicted their tenants. While the blight provided the catalyst for the famine, "[t]he calamity was essentially man-made, a poison of blind politics, scientific ignorance, rural suppression, and enforced poverty." QUESTIONS: 1. Where is Ireland located ? 2. Who controlled it by 1500 ? 3. Describe how the English/British ruled Ireland .. and why ? 4. Where did the potato come from .. what was it part of ... "the historical term" ? 5. Why was the potato popular in Ireland? PAGE 4 H07 - 26 The Irish Potato Famine 2/16/2016 6. What occurred during the 19th century in Ireland ... from an agricultural standpoint ? 7. What was the impact on Ireland ? 8. What position did the British take towards this problem & Ireland in general ? 9. State 3 results of the Irish Potato Famine. 10. What do you think Irish-English relations are like today ? 11. Which title best completes this partial outline? I. _____________________________ A. Mass starvation in Ireland (1845Ð 1850) B. Partition of India (1947) C. Latin Americans seeking jobs in the United States (post- World War II) D. Ethnic cleansing in the Balkans (1990s) (1) Causes of Global Migrations (2) Causes of Industrialization (3) Reasons for Colonialism (4) Reasons for Cultural Borrowing [January 2003] 12. The main cause of the mass starvation in Ireland during the 19th century was the (1) British blockade of Irish ports (2) failure of the potato crop (3) war between Protestants and Catholics in northern Ireland (4) environmental damage caused by coal mining [ June 2001] 13. °Failure of the potato crop contributes to famine in Ireland. ° Continued drought overtakes farmlands in Africa. ° Herders search for an oasis for their animals. Which conclusion can be drawn from these statements? (1) People can control their environments to suit their needs. (2) Environmental conditions often cause people to migrate. (3) Geography has a positive impact on people. (4) Climatic conditions have led to an even distribution of population. [ June 2002] 14. Which area was once controlled by Britain, suffered a mass starvation in the 1840s, and became an independent Catholic nation in 1922? (1) Scotland (2) Ghana (3) India (4) Ireland [August 2006] 15. 16. Between 1845 and 1860, which factor caused a large decline in Ireland's population? (1) famine (2) civil war (3) plague (4) war against Spain What was an immediate result of the mass starvation in Ireland in the late 1840s? (1) expansion of the Green Revolution to Ireland (2) acceptance of British rule by the Irish (3) migration of many Irish to other countries (4) creation of a mixed economy in Ireland PAGE 5 [January 2005] [June 2007]