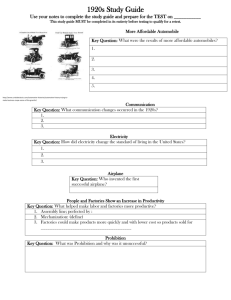

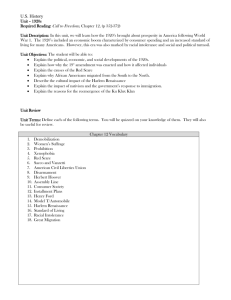

HarlemRenaissance

advertisement

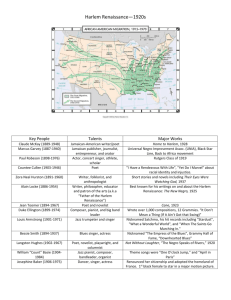

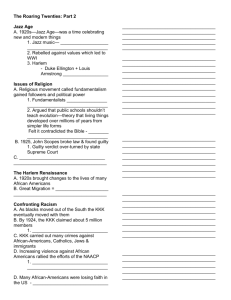

Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance Presentation Introduction The 1920s were a complex and interesting time in American cultural history. A number of different appellations have characterized the age, among them the “Jazz Age” and, at least for the latter half of the decade, the Harlem Renaissance. There were a number of tributaries for the changes in mores and thought that characterized the decade, among them differing reactions to the aftermath of what was then called “The Great War,” growing anti-immigrant sentiment in different parts of America, increasing black migration from the South to the urban industrial centers of the north, and of course, the passage of the 18th Amendment in 1919 beginning the era of Prohibition. It is in the midst of these and other cultural and societal changes that we must locate the Harlem Renaissance. We should also be mindful, as musicologist Sam Floyd points out, of the differences between the Harlem Renaissance and its European predecessor. He writes, “[u]nlike the European Renaissance, which took place in western Europe from the fourteenth through sixteenth centuries and was largely fueled by the rediscovery of the Greek cultural legacy, the Negro Renaissance had no large body of written texts.…But African Americans were inspired by a growing awareness of the African civilizations that had flourished along the Nile, Tigris, and Euphrates rivers. They longed to restore African culture to a position of respect, and they used what they knew of African and African-American folk art and literature of times past and current in an attempt to create new cultural forms. It is in this sense that the period was called a renaissance” (Floyd 1995:106). It is also important to remember that this rebirth or flowering of African creativity in the arts had not previously taken place in Harlem. In her excellent and exhaustive book Terrible Honesty (1995), Ann Douglas points out that, at the turn of the century, Harlem had been an immigrant neighborhood composed of British, German, Irish and Jewish residents. She details how housing speculation and shrewd real estate deals transformed the neighborhood in less than twenty years to an almost purely black enclave. Accounts from the white press in 1911 referred to the influx of African Americans as a “Negro invasion” that “must be valiantly fought.” Alluding to the Middle Ages in another way, fleeing white residents also spoke of their fear of a “black plague.” Aims of the Harlem Renaissance One could say that Renaissance officially began with the publication of Alain Locke’s The New Negro in 1925. In that collection, various contributors undertook to explain the “riches of the black heritage” (Douglas 1995:332). The New Negro’s notion of his heritage, from the standpoint of many of the essayists, included black and white traditions. Indeed, one scholar writes that the “New Negro wanted not distance from white America but more power and recognition within it” (Douglas 1995:304). Part of the rationale, as black leaders like James Weldon Johnson saw it, was that African Americans were an essential part of the American fabric: unlike hyphenated immigrants who had been “added to America,” African Americans had been here from the beginning. W.E.B. DuBois, similarly, felt that African Americans were the first, “the ur-American[s], and might be the last. His message became the credo of the New Negro in the 1920s. The Harlem Renaissance was founded on DuBois’s assertion that African Americans possessed a rich and significant culture of their own, on that predated, and in part determined, that of white America and entitled its participants to full rights in American society” (Douglas 1995:308–9). In particular, Booker T. Washington’s policy of humility and accommodation was seen as a failure (312–3). Whereas Washington had emphasized “fighting the battle” in the South, these new individuals were committed to fighting it in the cities, guided by James Weldon Johnson’s statement that “A people that has produced great art and literature has never been looked upon as distinctly inferior” (quoted from Douglas, 313). Seeking varied forms of support for African American novelists, poets, visual artists and musicians, the architects of the Renaissance hoped to challenge demeaning stereotypes of African Americans. Why? There seemed to be few viable political alternatives. Some attempts had been made, by DuBois for example, to encourage black voters to support Democratic candidates, thereby assuring that no party could assume African American support in elections. Such tactics were not very successful, however, for New York was still dominated by machine politics and patronage that had no room for African Americans without economic power. In a sense, then, the Harlem Renaissance was a test case, another tactic for achieving equality when political means didn’t seem viable. A number of important figures emerged from this “test case,” including writers Countee Cullen, Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, Nella Larsen and Claude McKay and visual artists like Aaron Douglas. Music in the Harlem Renaissance I: Art Music But what about music? Where was its place in this flowering of African American creativity? Musical production was expected to follow the same general patterns that literary and artistic work were. Sam Floyd explains, “Musically, the idea was to produce extended forms such as symphonies and operas from the raw materials of spirituals, ragtime, blues and other folk genres. The movement’s first successful effort in the transformation of folk music into ‘high art’ was [R. Nathaniel] Dett’s [1882– 1943]…The Chariot Jubilee (1921). [William Grant] Still’s Afro-American Symphony (1930) was the movement’s crowning achievement” (Floyd 1995:107). The music of jazz musicians like Duke Ellington and Fletcher Henderson or that of classic blues singers like Bessie Smith were seen as “folk forms” that needed to be transformed along the same lines as European composers like Mussorgsky and Bartók had transformed folk melodies before they could “elevate” the race. Indeed, much of the work of composer George Gershwin fits this bill, particularly works like his 1924 piano sonata, Rhapsody in Blue, and Porgy and Bess. David Levering Lewis (1989) notes that “Afro-American music had always been a source of embarrassment to the Afro-American elite. The group continued to be more than a little annoyed by the singing of spirituals long after James Weldon Johnson and Alain Locke had proclaimed them America’s most precious, beautiful, and original musical expression” (173). In contrast, they, and many white compatriots, were quite supportive of achievements in the European concert realm. Roland Hayes began to receive great praise for his work following his Town Hall concert in December of 1923. And when Jules Bledsoe did a concert of music by Purcell, Handel, Bach and Brahms in April of 1924, things started to change. In fact, Hayes’s performance of spirituals was accepted partially because of the acclaim he received from the white press. As Lewis sarcastically writes, “Now that Roland Hayes had taken spirituals to the concert hall, cultured Afro-Americans were suddenly as pleased as Southern planters to hear them again” (163). While there is much to criticize in narrow vision of older Harlem Renaissance leaders, they encouraged the development of the careers of outstanding musicians in the “classical” vein, performers who drew upon an extensive, but scarcely documented tradition of African American performance and composition using European models. Two of the most famous interpreters of spirituals were Paul Robeson and Marian Anderson, both of whom would become important figures in American society. Though both of these recordings date from the 1930s, they present a glimpse of the basic concert hall rendering of spirituals in the Harlem Renaissance: the solo voice accompanied by piano. Outside the concert hall, spirituals were more likely to be performed communally, in the context of worship, with emphasis on rhythmic and melodic improvisation rather than arrangement and execution. We’ll first hear Anderson performing an arrangement of “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired” followed by Robeson performing “Go Down, Moses.” Note how different these versions sound from a more down-home, gospel-style performance of these tunes. Those two examples represent one way in which “folk” materials were made respectable. William Grant Still’s Afro American Symphony, composed in 1930, represents an even more ambitious attempt. The twelvebar blues progression, by then a familiar harmonic form, was not at all associated with concert music. Still, however, inventively wedded the form and harmonic progression associated with the blues with the “first movement” form for the symphony. We’ll first hear a simplified example of a twelve-bar blues from a demonstration cassette for a popular jazz textbook. Afterwards, we’ll hear its realization in a performance by Howlin’ Wolf in the 1960s. Lastly, we’ll hear Still’s adaptation in his symphony. Music in the Harlem Renaissance II: Vernacular Music There were, of course, criticisms of this approach toward music-making. These criticisms strongly voiced by musicians and writers who celebrated vernacular musics. Poet Langston Hughes, in this recording from the late 1950s, recites one of his poems that addresses the “refining” of folk forms. He, along with Zora Neale Hurston, sought to embrace African American “folk” forms, to see them as valid in their own right. And, in his famous 1926 essay “The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain,” Hughes pointedly criticized the viewpoint of his elders: “Let the blare of Negro jazz bands and the bellowing voice of Bessie Smith singing blues penetrate the closed ears of the colored near-intellectuals until they listen and perhaps understand. Let Paul Robeson singing ‘Water Boy,’ and Rudolph Fisher writing about the streets of Harlem, and Jean Toomer holding the heart of Georgia in his hands, and Aaron Douglas drawing strange black fantasies cause the smug Negro middle class to turn from their white, respectable, ordinary books and papers and catch a glimmer of their own beauty. We younger artists who create now intend to express our individual darkskinned selves without fear or shame. If white people are pleased, we are glad. If they are not, it doesn’t matter. We know we are beautiful. And ugly too. The tom-tom cries and the tom-tom laughs” (Ogren 1989:132). Likewise, both Fletcher Henderson and Duke Ellington recorded tunes that signified on what the Renaissance leaders thought about their music, the former recording “Dicty Blues” in 1923 and the latter “Dicty Glide” in 1927 (108). In describing his title for the composition, Ellington noted that the dance called the dicty glide required “a lofty carriage” (see Tucker 1993:88). Note how this tune in a sense communicates through its low dynamics and muted sonorities “gentility,” “sweetness” and “refinement.” If those musics weren’t part of the program, they surely formed part of the backdrop and provided ambiance for it. Along with nascent jazz and blues, the stride piano work of musicians like Fats Waller, James P. Johnson and Willie “the Lion” Smith were captivating audiences. Floyd goes on to argue that as the decade progressed, jazz became the most acceptable of the vernacular genres, particularly via the work of bands led by Ellington and Henderson. In brief descriptions of their work, he shows how they too took folk forms and materials and employed them in larger band settings, with expanded harmonic and timbral resources. Particularly praised are songs like Henderson’s 1926 “The Stampede” with its riffs and call and response figures and Ellington’s 1927 “East St. Louis Toodle-oo” with its vocalized trumpet and trombone work, its contrasting sections, and its references to New Orleans style collective improvisation. References Douglas, Ann. Terrible Honesty: Mongrel Manhattan in the 1920s. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 1995. Floyd, Samuel A., Jr. The Power of Black Music: Interpreting Its History from Africa to the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1995. Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. Ogren, Kathy J. The Jazz Revolution: Twenties America and the Meaning of Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press, 1989. Tucker, Mark, ed. The Duke Ellington Reader. New York: Oxford University Press, 1993.