Paradoxes of Constitutional Democracy

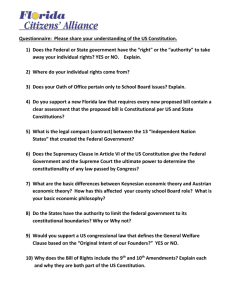

advertisement