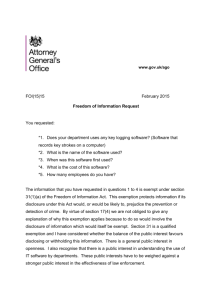

Freedom of Information Act 1982:Fundamental Principles and

advertisement