Increased Occurrence of Tracheal Intubation Associated Events

advertisement

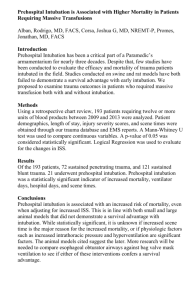

Increased Occurrence of Tracheal Intubation Associated Events during Nights and Weekends in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit Kyle J Rehder MD FCCP1, John S Giuliano Jr MD FAAP2, Natalie Napolitano MPH RRT-NPS FAARC3, David A Turner MD FCCM FCCP1, Gabrielle Nuthall MBChB FRACP CICM4, Vinay M Nadkarni MD FCCM5, Akira Nishisaki MD MSCE5 for the NEAR4KIDS and PALISI investigators Department of Pediatrics, Division of Pediatric Critical Care Medicine, Duke Children’s Hospital, Durham, NC. 2 Department of Pediatrics, Division of Critical Care Medicine, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT. 3 Department of Nursing, Respiratory Care, and Neurodiagnostics, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA. 4 Division of Pediatric Intensive Care, Starship Children’s Health Center, Grafton, Auckland, New Zealand. 5 Department of Anesthesiology and Critical Care Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Philadelphia, PA. 1 Drs. Rehder and Giuliano Jr shared first authorship. Institution where study performed: Twenty centers in the National Emergency Airway for Children Registry (NEAR4KIDS), data analysis performed at Duke University Medical Center (Durham, NC) and Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia (Philadelphia, PA) Corresponding Author / Address for reprints: Kyle Rehder, MD Division of Pediatric Critical Care DUMC Box 3046 Durham, NC 27710 Funding: Endowed Chair, Critical Care Medicine, The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, Unrestricted Research fund from Laerdal Foundation Acute Care Medicine, AHRQ 1R03HS021583- 01, AHRQ 1 R18 HS022464-01 1 Supplemental digital content is available for this article. Direct URL citations appear in the printed text and are provided in the HTML and PDF versions of this article on the journal’s website (http://journals.lww.com/ccmjournal). Keywords: airway, intubation, pediatric, personnel staffing, in-house, patient safety Copyright form disclosures: Dr. Napolitano served as a board member for AARC and AAN (only compensation is travel to meetings), consulted for AAN (Qualitative project on Decisions of Families for Asthma Care), lectured for Draeger Medical, and received support for travel from AARC (for AARC Conference). Her institution has a Pending Patent for NIV Mask and received grant support from the AHRQ, CVS Health, Aerogen, Nihon Kohden, and AHRQ. Dr. Nuthall is employed by Auckland District Health Board. Her institution received other support from A+ Trust (Contribution to research nurses salary to collect ongoing data for the project). Dr. Nadkarni’s institution received grant support from AHRQ (R18 Grant). Dr. Nishisaki received support for article research from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality). His institution received grant support from Improving the safety and quality of tracheal intubation in pediatric ICUs (AHRQ R18HS022464) and from Evaluating safety and quality of tracheal intubation in pediatric ICUs (AHRQ R03HS021583) (Supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality [AHRQ]) and received grant support from Evaluation of Mainstream Capnography (Nihon Kohden America). The remaining authors have disclosed that they do not have any potential conflicts of interest. 2 Abstract Objectives: Adverse tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) are common in PICUs. Prior studies suggest provider and practice factors are important contributors to TIAEs. Little is known about how the incidence of TIAEs is affected by the time of day, day of the week, or presence of in-hospital attending-level intensivists. We hypothesize that tracheal intubations occurring during nights and weekends are associated with a higher incidence of TIAEs. Design: Retrospective observational cohort study Setting: Twenty international PICUs Subjects: Critically ill children requiring tracheal intubation Interventions: None Measurements and Main Results: We analyzed 5096 tracheal intubation courses from July 2010 to March 2014 from the prospective multicenter National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS). Incidence of a priori defined TIAEs was the primary outcome. Occurrence of any TIAEs and severe TIAEs were more common during nights (19:00-06:59) and weekends compared to weekdays (19% vs. 16%, p=0.01; 7% vs. 6%, p=0.05, respectively). This difference was significant in emergent intubations after adjusting for site level clustering and patient factors: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for any TIAEs: aOR 1.20, CI951.02-1.41, p=0.03; but not significant in non-emergent intubations: aOR 0.94, CI95 0.63-1.40,p=0.75. For emergent intubations, PICUs with home call attending coverage had a significantly higher incidence of TIAEs during nights and weekends (aOR 1.29: 1.01-1.66, p=0.04), and this difference was attenuated in PICUs with in-hospital attending coverage (aOR: 1.12, 95% CI 0.91-1.39, p=0.28). Conclusions: Higher incidence of TIAEs was observed during nights and weekends. This difference was primarily attributed to emergent intubations. In-hospital attending physician 3 coverage attenuated this discrepancy between weekdays vs. nights and weekends, but was not fully protective for TIAEs. 4 Introduction Pediatric advanced airway management is challenging and can result in significant morbidity or mortality1-4. Patients requiring emergent tracheal intubation (henceforth referred to as ‘intubation’) rather than non-emergent intubation are at the greatest risk for complications1,5. Some data also suggest worse outcomes for critically ill patients during nights and weekends compared to traditional weekday staffing models1,6-9. Furthermore, intubation attempts by inexperienced providers have been associated with an increased incidence of adverse events3. Considering these factors and others, many children’s hospitals have employed 24-hour inhospital intensive care attending coverage with the intent to mediate these risks. However, the presence of in-hospital coverage has not consistently demonstrated improved patient outcomes1012 . The aim of this study was to evaluate the effect of time of day and 24/7 in-hospital coverage on tracheal intubation associated events (TIAEs) and outcomes in the PICU using the National Emergency Airway Registry for Children (NEAR4KIDS) database5. We hypothesized that intubations during nighttime and weekends are associated with higher occurrences of adverse TIAEs. Since night and weekend intubations are more likely emergent and at higher risk for TIAEs, we further evaluated our hypothesis among the intubations for emergent indications. We then evaluated the impact of in-hospital coverage on TIAEs during nights and weekends. 5 Materials and Methods The previously described NEAR4KIDS registry is a multicenter quality improvement collaborative to prospectively collect safety and quality data on intubations in PICUs5. Data collection was either approved or declared exempt by the Institutional Review Board at each participating center. Data collection included basic patient demographics, provider presence, intubating provider specialty and level of training, equipment used, and details on the intubation encounter. Centers also reported if the intubation was elective (non-emergent) or emergent. An “encounter” was defined as one completed episode of advanced airway management intervention, typically ending with successful intubation. Within each intubation encounter, a “course” encompassed one method or approach to secure an artificial airway (e.g., switching from direct laryngoscopy to fiber optic laryngoscopy was defined as two courses), while an “attempt” was defined as a single distinct advanced airway maneuver (e.g., insertion of a device such as laryngoscope, endotracheal tube, or laryngeal mask into patient’s mouth or nose) ². Pediatric Index of Mortality (PIM2) was captured at the time of PICU admission13. Adverse TIAEs were defined a priori. Severe TIAEs were defined as cardiac arrest, esophageal intubation with delayed recognition, emesis with witnessed aspiration, hypotension requiring intervention (fluid and/or pressors), laryngospasm, pneumothorax or pneumomediastinum, or direct airway injury. Non-severe TIAEs included mainstem bronchial intubation (confirmed by chest radiograph), esophageal intubation with immediate recognition, emesis without aspiration, hypertension requiring therapy, epistaxis, dental or lip trauma, medication error, arrhythmia, or pain and/or agitation requiring additional medication with delay in intubation. 6 Intubation time was recorded on the data collection form for each intubation encounter. ‘Weekdays’ were defined as 07:00-18:59, Monday through Friday (i.e. excluding nights and weekends). ‘Nights and weekends’ included (1) weeknights (defined as 19:00-06:59 the next morning), and (2) weekends (defined as Friday at 19:00-06:59 Monday morning). For the data collection period, centers identified themselves as having 24/7 in-hospital pediatric intensivist coverage or home coverage and provided the start date for in-hospital coverage (to properly identify intubations that occurred under in-hospital coverage). Statistical analysis The primary outcome was occurrence of any TIAE during an intubation course. The primary exposure variable was weekday vs. nights and weekends. Non-emergent intubation status was considered as an effect modifier and analyses were stratified by emergent status when the association of TIAEs and weekday status was evaluated. For the analysis of in-hospital coverage, only emergent intubations were included to focus on those intubations where inhospital coverage was most likely to affect outcomes. Summary statistics are provided as percentages for categorical variables or median and interquartile ranges (IQR) for continuous variables. Dichotomous categorical variables were analyzed using chi-square test, while continuous variables were compared using Wilcoxon rank-sum test. Statistical analysis was performed with JMP 11 (SAS, Cary, NC) and STATA 11.2 (Stata Corp, College Station, TX). A random effect multivariate logistic regression model was developed with the site as a group variable (20 sites) and occurrence of TIAE as a dichotomous outcome. Factors associated with weekday vs. night and weekend status in the univariate analysis (p<0.1) and also known to be associated with TIAEs in previous studies were included as covariates in this model. We also 7 conducted sensitivity analyses using two alternative definitions for nights (nighttime 16:00 – 06:59, and nighttime 18:00-06:59). P-values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Results Patient demographics and provider characteristics Five thousand ninety-six intubation courses (representing 4775 encounters) were reported at 20 participating institutions during the study period (July 2010 to March 2014). A median of 162 (IQR: 81-347) courses were reported from each site. Patient demographics and indications for intubation are reported in Table 1. Respiratory failure, shock status and emergent intubations were associated with night and weekend intubations. Of note, admission PIM2 scores and history of difficult airway were not associated with time of intubation. First attempt intubation providers for the course are reported in Table 2. Weekday vs. night and weekend intubations and outcomes Overall, 2702 intubation courses (53%) occurred during nights and weekends. Adverse TIAEs were reported in 898 (18%) of all intubation courses, and severe TIAEs were reported in 319 (6%). Tracheal intubations during nights and weekends were associated with a higher occurrence of TIAEs, as shown in Table 3. This was primarily attributed to emergent intubations. This difference was significant in emergent intubations after adjusting for site level clustering and patient factors: adjusted odds ratio (aOR) for any TIAEs: aOR 1.20, 95% Confidence Interval (CI95) 1.02-1.41, p=0.03; but not significant in non-emergent intubations: aOR 0.94, CI95 0.63-1.40, p=0.75., 8 Attending-level providers were more likely to be present at weekday intubations. Pediatric residents were more likely to be involved as first intubators during nights and weekends. This latter finding was consistent for both non-emergent and emergent intubations. 24/7 in-hospital intensivist coverage and attending physician presence at emergent intubations Nine of 20 (45%) PICUs reported having in-hospital attending physician coverage during the study period: seven PICUs had in-hospital coverage throughout and two PICUs transitioned from home coverage to an in-hospital coverage system during the study period. Overall, 56% of emergent, night and weekend intubations occurred in PICUs with in-hospital coverage. Table 4 displays the occurrence of TIAEs and severe TIAEs, as well as provider characteristics for emergent intubations, based on the presence of in-hospital coverage. Emergent intubations at the PICUs with in-hospital attending coverage were associated with a higher occurrence of TIAEs during weekdays as well as nights and weekends. For emergent intubations, the odds of having a TIAE were significantly higher in night and weekend intubations vs. weekday intubations (OR 1.29, p=0.04, Table 5) in PICUs with home call attending coverage, but not for PICUs with in-hospital coverage (OR: 1.12, p=0.28) after adjusted for covariates associated with time of intubation (respiratory failure, shock status) and age. Attending physicians in in-hospital coverage were more likely than those in home coverage to be present for both night and weekend and weekday intubations, although home coverage attending physicians were commonly present at night and weekend intubations (68%). Attending physician presence for emergent, night and weekend intubations were not significantly 9 associated with occurrence of any TIAEs (attending presence: 393/1923 (20%) vs. attending not present: 70/319 (18%), p= 0.27). This was also the case for the occurrence of severe TIAEs (146/ 1,923 (7%) vs. 29/ 389 (7%), p= 0.93). Attending physicians were more likely and pediatric residents were less likely to be the first intubating providers for night and weekend intubations in PICUs with in-hospital coverage (Table 4). Sensitivity analysis with alternative definitions for nighttime hours Alternative definitions of nighttime (18:00-06:59 and 16:00-06:59) were also used to evaluate the association of TIAEs with nights and weekends. For the first definition (nighttime: 18:00-06:59), 2871 intubation courses were classified as intubations during nights and weekends. The night and weekend hours were significantly associated with any TIAEs (weekday 16% vs. night and weekend 19%, p=0.01) but not with severe TIAEs (6% vs.7%, p=0.11). For the second definition (16:00-06:59), 3337 intubation courses were classified as intubations during nights and weekends. The night and weekend hours were significantly associated with both any TIAEs (weekday 16% vs. night and weekend 19%, p=0.004) and severe TIAEs (weekday 5% vs. night and weekend 7%, p=0.03). Multivariate analyses with these two alternative definitions revealed that in-hospital attending coverage and the occurrence of TIAEs were significantly associated for weekday intubations but not for night and weekend intubations, which was consistent with the original definition of nighttime (19:00-06:59) (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2, Supplemental Digital Content 1, ). 10 Discussion Our study using a large multicenter intubation quality improvement database (NEAR4KIDS) demonstrated an increased occurrence of TIAEs for tracheal intubations performed during nights and weekends. This remained significant after adjusting for patient factors and excluding non-emergent intubations. When in-hospital attending coverage was compared against home call coverage, the increased risk of TIAEs during nights and weekends persisted in home coverage models but not in in-hospital coverage, suggesting a protective effect of 24/7 in-hospital coverage. Because in-hospital coverage does not assure attending presence at each intubation, we separately analyzed documented attending presence regardless of the hospital model. Attending physician presence at the bedside was not associated with occurrence of TIAEs among night and weekend emergent intubations. This is the largest study to date evaluating the association between time of day and TIAEs in multiple PICUs. Our study adds to the growing body of literature evaluating patient care in intensive care units outside of traditional weekday work hours. Similar to much of the other published literature, our study demonstrates inconsistency in outcomes by time and day of week. However, this variability is likely multifactorial. In evaluating this finding, we must consider the night and weekend differences in patient population and disease processes, indications for the procedure, unit staffing, and provider experience level. Several studies have demonstrated worse outcomes for patients admitted during nights and weekends7,14-16, however, this discrepancy may be secondary to confounders such as severity of illness or admitting diagnoses17,18. Less data exist regarding procedure outcomes by time of day. In a single center pediatric study, Carroll et al demonstrated a three-fold risk of 11 complications for intubations occurring during nights and weekends1. Our data supports this finding in a larger multicenter cohort. Concern over differences in outcomes during off-hours have led to guidelines recommending 24/7 in-hospital intensivist coverage of all Level I and Level II adult intensive care units19. However, the published data regarding in-hospital coverage is unclear regarding its effect on patient outcomes11,20-23. Furthermore, aggregate outcomes may not directly assess the impact of in-hospital attending coverage, as these outcomes are also affected by care provided during weekday hours. Investigating procedural outcomes during nights and weekends provides the unique opportunity to measure the immediate effect of in-hospital attending coverage. In our study, the association between nights and weekends and occurrence of TIAEs was somewhat attenuated, but not eliminated, in the presence of in-hospital attending coverage. This result suggests that the higher intubation risks associated with nights and weekends may be mainly from patient factors. While we may have been unable to fully adjust for patient-level factors in our multivariate model, it is also possible that the occurrence of TIAEs were more susceptible to non-attending physician ICU staffing (physician trainees, nurses, respiratory therapists), which may have been quite different during nights and weekends. We may have also over-estimated the clinical impact of having in-hospital attending physician coverage in our hypothesis. Our recent publication demonstrated similar intubation skills among pediatric critical care medicine fellows and attending physicians when analyzed with TIAEs as an outcome3, suggesting that attending presence may not be the most important factor in minimizing TIAEs. It is important to note that even when present at intubations, attending physicians were rarely the first attempt providers (Table 4). 12 Our study also demonstrated increased occurrence of TIAEs among intubations with 24/7 in-hospital attending coverage during the weekday hours (OR 1.53), with a lesser, nonsignificant increase during nights and weekends (OR 1.33). It is likely that hospitals choosing to provide in-hospital coverage represent a higher acuity population, which could explain this discrepancy. While there may be other inherent differences in the patient populations or provider characteristics as confounders for the increased TIAE incidence with in-hospital coverage, it is improbable that differences attributed to the coverage model would lead to a larger discrepancy during weekday hours. This study has several limitations. It is an observational study relying on self-reported data; however, reporting bias is minimized by prospective data collection and careful monitoring of center compliance5. We are unable to account for unmeasured patient and institutional factors which may affect the incidence of TIAEs, including prior institutional team training or the presence of difficult airway algorithms. The data did not specify when the attending physician arrived at the intubation scene; therefore we cannot report the degree of attending physician involvement for each intubation. Also, our analysis did not include patient outcomes beyond the intubation encounter, including length of ventilation or mortality. The data collection form does not specify when the attending arrives, therefore we cannot report which intubations had attending presence for the entire procedure. Finally, while this study reports a large number of intubation courses from twenty academic centers, this cohort may not be representative of all intubations that occur in PICUs, particularly intubations that occur in community PICUs. While PICUs strive to provide equivalent care at any hour of the day, this study demonstrates that there is variability in the incidence of TIAEs between traditional weekday work hours and those occurring during nights and weekends. This variance remains present after 13 adjusting for patient factors and excluding non-emergent intubations, and was somewhat attenuated in the presence of in-hospital attending coverage. Further investigation is needed to elucidate factors which contribute to this variance, and to determine processes which may lead to safer tracheal intubations for this high-risk population. Conclusions: Adverse TIAEs are more common during nights and weekends. This association remained significant after adjusting for patient factors. Presence of 24/7 in-hospital attending coverage was partially protective for TIAEs during nights and weekends. Further research is required to identify explanatory factors. 14 Acknowledgements: We would like to thank Hayley Buffman for her tireless efforts as the coordinator for the multicenter NEAR4KIDS registry. 15 References 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. 16. Carroll CL, Spinella PC, Corsi JM, Stoltz P, Zucker AR. Emergent endotracheal intubations in children: be careful if it's late when you intubate. Pediatr Crit Care Med. May 2010;11(3):343348. Nishisaki A, Ferry S, Colborn S, et al. Characterization of tracheal intubation process of care and safety outcomes in a tertiary pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatr Crit Care Med. Jan 2012;13(1):e5-10. Sanders RC, Jr., Giuliano JS, Jr., Sullivan JE, et al. Level of trainee and tracheal intubation outcomes. Pediatrics. Mar 2013;131(3):e821-828. Easley RB, Segeleon JE, Haun SE, Tobias JD. Prospective study of airway management of children requiring endotracheal intubation before admission to a pediatric intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. Jun 2000;28(6):2058-2063. Nishisaki A, Turner DA, Brown CA, 3rd, Walls RM, Nadkarni VM. A National Emergency Airway Registry for children: landscape of tracheal intubation in 15 PICUs. Crit Care Med. Mar 2013;41(3):874-885. Pronovost PJ, Angus DC, Dorman T, Robinson KA, Dremsizov TT, Young TL. Physician staffing patterns and clinical outcomes in critically ill patients: a systematic review. JAMA. Nov 6 2002;288(17):2151-2162. Cavallazzi R, Marik PE, Hirani A, Pachinburavan M, Vasu TS, Leiby BE. Association between time of admission to the ICU and mortality: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Chest. Jul 2010;138(1):68-75. Gajic O, Afessa B, Hanson AC, et al. Effect of 24-hour mandatory versus on-demand critical care specialist presence on quality of care and family and provider satisfaction in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. Crit Care Med. Jan 2008;36(1):36-44. Wallace DJ, Angus DC, Barnato AE, Kramer AA, Kahn JM. Nighttime intensivist staffing and mortality among critically ill patients. The New England journal of medicine. May 31 2012;366(22):2093-2101. Gajic O, Afessa B. Physician staffing models and patient safety in the ICU. Chest. Apr 2009;135(4):1038-1044. Kerlin MP, Small DS, Cooney E, et al. A randomized trial of nighttime physician staffing in an intensive care unit. The New England journal of medicine. Jun 6 2013;368(23):2201-2209. Rehder KJ, Cheifetz IM, Markovitz BP, Turner DA. Survey of in-house coverage by pediatric intensivists: characterization of 24/7 in-hospital pediatric critical care faculty coverage. Pediatr Crit Care Med. Feb 2014;15(2):97-104. Slater A, Shann F, Pearson G. PIM2: a revised version of the Paediatric Index of Mortality. Intensive Care Med. Feb 2003;29(2):278-285. Sorita A, Ahmed A, Starr SR, et al. Off-hour presentation and outcomes in patients with acute ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-analysis. European journal of internal medicine. Apr 2014;25(4):394-400. Arias Y, Taylor DS, Marcin JP. Association between evening admissions and higher mortality rates in the pediatric intensive care unit. Pediatrics. Jun 2004;113(6):e530-534. Bell CM, Redelmeier DA. Mortality among patients admitted to hospitals on weekends as compared with weekdays. The New England journal of medicine. Aug 30 2001;345(9):663-668. 16 17. 18. 19. 20. 21. 22. 23. McCrory MC, Gower EW, Simpson SL, Nakagawa TA, Mou SS, Morris PE. Off-hours admission to pediatric intensive care and mortality. Pediatrics. Nov 2014;134(5):e1345-1353. Peeters B, Jansen NJ, Bollen CW, van Vught AJ, van der Heide D, Albers MJ. Off-hours admission and mortality in two pediatric intensive care units without 24-h in-house senior staff attendance. Intensive Care Med. Nov 2010;36(11):1923-1927. Haupt MT, Bekes CE, Brilli RJ, et al. Guidelines on critical care services and personnel: Recommendations based on a system of categorization of three levels of care. Crit Care Med. Nov 2003;31(11):2677-2683. Arabi Y. Pro/Con debate: should 24/7 in-house intensivist coverage be implemented? Crit Care. 2008;12(3):216. Nishisaki A, Pines JM, Lin R, et al. The impact of 24-hr, in-hospital pediatric critical care attending physician presence on process of care and patient outcomes*. Crit Care Med. Jul 2012;40(7):2190-2195. Rehder KJ, Cheifetz IM, Willson DF, Turner DA. Perceptions of 24/7 in-hospital intensivist coverage on pediatric housestaff education. Pediatrics. Jan 2014;133(1):88-95. Reriani M, Biehl M, Sloan JA, Malinchoc M, Gajic O. Effect of 24-hour mandatory vs on-demand critical care specialist presence on long-term survival and quality of life of critically ill patients in the intensive care unit of a teaching hospital. J Crit Care. Dec 13 2011. 17