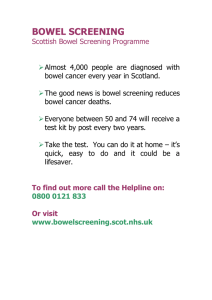

7. Bowel screening pathway

advertisement