1221volcano - National Geographic News

advertisement

1221volcano

Mexico’s Popocatépetl: To Flee or Not To Flee

By Donald Smith

12/21/2000

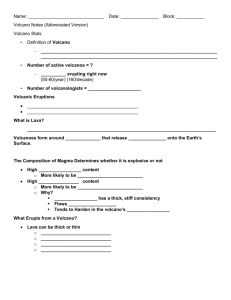

<b>MANY WAYS TO DIE</b>

<p>Death by volcano can come in many forms. In 1985 a tidal wave of mud from Colombia’s Nevado del

Ruiz smothered and crushed 23,000 people. History’s deadliest eruption claimed 92,000 Indonesians in

1815; but only 12,000 died from the blast. The rest starved after their crops and livestock were

destroyed.</p>

<p>The mantle of molten rock that cloaks Earth’s metallic core is constantly agitated as it rises, cools and

sinks, creating tremendous pressures beneath the Earth’s relatively thin crust. Periodically, liquefied rock

called magma spouts from the surface in the form of lava. Eruptions may be sudden and violent, like

1991’s eruption of Mount Pinatubo in the Philippines. Slower, quieter eruptions, like that of Hawaii’s

Mauna Loa in 1984, give people plenty of time to get out of the way.</p>

<p>Volcanologists try to predict eruptions by observing changes in a volcano’s shape, tracking seismic

activity, and noting emissions of water vapor and other gases. But predictions are still imprecise, and local

residents often balk at leaving.</p>

Thousands of Mexicans have refused to heed government warnings of death and destruction after the latest

eruptions of Popocatépetl, the nation’s second tallest volcano. U.S. scientists are especially interested in

what is going on because of “Popo’s” geological similarities to volcanoes that threaten communities in the

Cascade Range in Washington, Oregon, and California.

<LI> Often called “Popo” for short, Mexico’s Popocatépetl is one of the world’s most active volcanoes.

<LI> Previous eruptions of Popocatépetl, like the ones that occurred when the Spanish first arrived in what

is now Mexico, have been regarded as bad omens.

<LI> Across the globe, about 500 million people live in the dangerous shadows of roughly 550 active

volcanoes.

<LI> At any given moment, between 1 and 20 volcanoes worldwide are spewing ash and molten rock.

Government trucks racing through village streets blaring warnings didn’t do it. Neither did clanging church

bells, or soldiers begging residents to leave. Not even the sight of ash, smoke, and large, red-hot rocks

shooting 650 feet (200 meters) into the sky could convince thousands of Mexicans this week that the time

finally had come to flee Popocatépetl, the “friendly volcano.”

<p>As of Wednesday, authorities had managed to evacuate some 26,000 residents in three states

surrounding the volcano, and still were trying to convince an almost equal number to relocate to 180

refugee centers. While calling for calm, Mexican President Vicente Fox urged those in harm’s way to leave

immediately.</p>

<p><a href=javascript:popup('color.html','popup',530,500);><IMG SRC="color_sm.jpg" align=left

border=0 width=100 height=100></a>Although the volcano was relatively quiet as of dawn Thursday,

scientists and government officials continued to warn of the possibility of a cataclysmic eruption. Another

fear is that a 3,000-foot- (900-meter-) long glacier on the western face of the volcano could be loosened by

molten rock, causing massive mudslides. Officials have expanded the danger zone from 7.5 miles (12

kilometers) to 12.5 miles (20 kilometers), and are warning residents to stay away for another one to two

weeks.</p><p>

</p>Still, thousands either refuse to go or insist on returning before the danger has passed.

<p><a href=javascript:popup('greyscale.html','popup',530,500);><IMG SRC="greyscale_sm.jpg"

align=right border=0 width=100 height=100></a>“It’s their homes and their livelihoods that they’re being

asked to leave behind,” says U.S. Geological Survey volcanologist Rick Hoblitt. “I’ve witnessed this in a

lot of volcano crises. A lot of people refuse to believe there’s a problem.”</p>

<b><p>SIMILAR TO U.S. VOLCANOES</p></b>

<p>U.S. scientists like Hoblitt are especially interested in Popocatépetl because of its geological

similarities to volcanoes in the Cascade Range in Washington, Oregon and California. Future eruptions of

these volcanoes will threaten nearby communities in those states. In recent years, volcanologists working

for the U.S. Geological Survey and others from Arizona State University have been collaborating with

Mexican scientists studying Popocatépetl in hopes of gaining insights applicable to future eruptions in the

United States.</p>

<p>Relatively quiet since some notable rumbling in 1920-1922, Popocatépetl began showing signs of

renewed activity in 1994. Warnings by Mexican authorities were met with skepticism when Popocatépetl

began seriously misbehaving again two and a half years ago. It belched large volumes of ash, gas and

chunks of molten rock—all clear warning signals of a possible eruption. </p>

<p>Despite the volcano’s most recent display, the most spectacular in half a millennium, residents of closein villages give a variety of reasons for not wanting to leave. Many say they are reluctant to leave their farm

animals with no food.</p>

<p>“Some people will leave on their own,” says Hoblitt, who in the past has seen similar reactions in many

countries. “Others will go when the authorities recommend it, and there will always be people who refuse

to go under any circumstances. There’s usually a faction that distrusts the government and its motives. If

they’re forced out, they will find a way back in.”</p>

<p>Hoblitt recalls similar behavior in the days leading up to the catastrophic eruption of Mount Saint

Helens in the state of Washington in 1980.</p>

<p>“A lot of people felt there wasn’t a problem, and they wanted access to their property near the volcano.

In fact people were willing to engage in civil disobedience to get through police lines and get to their

property. The sheriff couldn’t control them.”</p>

<p><b>LORD OF RAIN AND SOIL</b></p>

<p>Snow-capped “Popo,” as many people call Mexico’s second tallest volcano, is just 42 miles (60

kilometers) southeast of Mexico City and its population of some 18 million. Standing 7,884 feet (5,452

meters) tall, it is one of the most active volcanoes in the country, with 15 eruptions recorded since the

arrival of the Spanish in A.D. 1519. Aztec Indians, who gave it the name “smoking mountain” in their

Nahuatl language, reported eruptions in 1347 and 1354.</p>

<p>In a 1520 letter to King Carlos V of Spain, explorer Hernando Cortés spoke in awe of the “great

column of smoke [that] comes forth and rises into the clouds as straight as a staff, with such force that

although a very violent wind continuously blows over the mountain range, yet it cannot change the

direction of the column.” Cortés sent a small expedition to “find out the secret of the smoke, where and

how it arose.”</p>

<p>Popo’s more recent activity has inspired fear. Authorities evacuated thousands from 19 villages after a

series of small earthquakes that began after midnight on December 21, 1994 signaled significant eruptions.

Many were reluctant to leave despite the huge gray ash cloud that drifted from the top of the volcano,

dusting the Puebla Valley with an estimated 8,000 tons of debris. The bodies of five mountaineers were

found with third degree burns near the crater.</p>

<p>However, most eruptions in the recent past have been relatively mild. Some 50 short displays of ash

and steam, sometimes accompanied by lava, have been noted since August 1997. Occasionally the blasts

have been powerful enough to shower the outskirts of Mexico City with ash.</p>

<p>Local residents have long marveled at an even more frequent phenomenon: the formation of rain clouds

over the peak, which bring life-giving showers to the fields. Mexicans always have taken a kindly view

toward Popo, some even revering it as a god of rain and soil because of the enriching effect that the ash has

on their fields.</p>

<p>But the 1994 outbursts served as a reminder that, like a restless giant, Popo also has the potential of

causing great harm. Since then government scientists have installed an elaborate monitoring system that

includes 23 video cameras to provide around-the-clock images. Stations set up to monitor cracks on the

volcano feed continuous streams of data to Mexico City’s National Disaster Prevention Center, where

researchers try to interpret activity beneath the surface. The government has also provided a total of 1,232

shelters to handle more than 300,000 people in the event of a major eruption.</p>

<p>Still, many refuse to leave when the warnings go out.</p>

<p>“Sometimes the most reluctant to go are old people,” says Hoblitt. “When you’re 90 years old, you may

rather die in your bed than be displaced.”</p>

<a href="http://www.nationalgeographic.com/eye/volcanoes/volintro.html ">Eye in the Sky:

Volcanoes @ nationalgeographic.com</a>

<a href="http://vulcan.wr.usgs.gov/volcanoes/mexico/popocatepetl/description_popo.html"

target="_new">Popocatépetl Volcano, Mexico</a>

<a href="http://volcano.und.nodak.edu/vwdocs/current_volcs/current.html" target="_new">Update

on Current Volcanic Activity</a>

<a href="http://volcanoes.usgs.gov/" target="_new">USGS Volcano Hazards Program</a>

<a href="http://volcano.und.nodak.edu/vw.html" target="_new">University of North Dakota’s

Volcano World</a>