Contribution of Bronchoscopy to the Diagnostic of Wheezy Children

advertisement

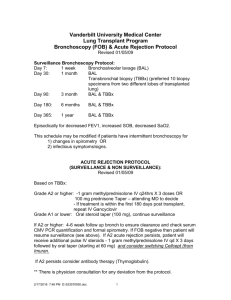

The role of bronchoscopy in wheezy children T. Nicolai Univ. Kinderklinik München im Dr. von Haunerschen Kinderspital Address for correspondence: Dr. T. Nicolai Univ. Kinderklinik Lindwurmstr.4 80337 München Germany Tel ++498951602841 Fax ++498951604409 Email tnicolai@med.uni-muenchen.de Abstract Introduction Recurrent or severe wheeze is a common diagnostic and therapeutic problem particularly in young children with respiratory symptoms (For the purpose of this discussion, we shall not consider the symptom of inspiratory stridor, although sometimes this is referred to as inspiratory wheeze). Diagnostic issues may include the search for “mechanical” causes of wheeze such as structural airway narrowing, tracheobronchomalacia, compression by intrathoracic structures such as vessels, heart, cysts, tumors or obstruction by a foreign body. If none of these differential diagnoses is likely, it would be helpful to determine whether the child belongs to one of the subgroup of recurrent or persistent wheeze phenotypes that are currently recognized: transient wheeze (which is associated with young maternal age and maternal smoking and will disappear after the first two years of life), viral associated wheeze (which lasts into school age but usually resolves then) and early manifestations of asthma which may persist. Therapy would clearly be different for a child belonging to one of the first two phenotypes compared to the last, but symptoms are identical and it only becomes clear in retrospect to which diagnostic group an individual patient belongs. Currently, no clinical parameter allow us to discern the patients early in their disease. The use of the flexible endoscope in investigating pediatric respiratory problems has become routine. The investigational use of bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) has led to significant insights into various pulmonary disease processes. Bronchoscopy in children has proved to be associated with little risk when performed in experienced centers (1), but other reports comparing multicenter data and sick children have shown that a few patients may still experience significant problems during the procedure, particularly if they had respiratory difficulties before the examination (2). Transient hypoxia was reported in 23% and one of 30 patients experienced a bradycardic event when children with wheeze underwent bronchoscopy and BAL (3), while a more recent study on bronchoscopy in 113 similar children reported hypoxic events in 6% of procedures (4). It is the purpose of this paper to discuss the place and utility of fiberoptic bronchoscopy in addressing the diagnostic issues outlined above. Bronchoscopy as a tool for differential diagnosis If there is an overwhelming likelihood of a diagnosis of asthma (e.g. both parents severe asthmatics and atopic dermatitis in the child) together with a typical chest auscultation and a clinical improvement after inhalation of betamimetics, no bronchoscopy is needed. If other causes of wheeze such as CF have been ruled out or are unlikely, or if the obstruction is unilateral and the patient has severe wheeze with a “tracheal” quality to it and /or the wheezing sound is associated with stridor, a bronchoscopy is usually warranted. Cardiac ultrasound, a chest x-ray including the laryngeal region, a CT scan (sometimes) and (mostly in older children) a lung function test are usually done before the endoscopy. Foreign bodies, tracheobronchial malacia, tracheal stenosis, vascular malformations (double aortic arch, pulmonary sling) and endobronchial tumors (carcinoid, mucoepideroid carcinoma, hemangioma, inflammatory pseudotumor) compromising the airway can thereby be identified. A study investigating 47 children with severe recurrent wheeze found structural abnormalities in 36% of bronchoscopies, one foreign body and visible inflammation in 27% (5). Tracheomalacia as a cause of wheeze is common after oesophageal atresia and some malformation syndromes but can occur in isolation. Other diagnostic options such as a lateral chest X-ray, CT scan, and MRI, will often not give clear enough information, but bronchoscopy will allow to make a definite diagnosis. While collapse of the tracheal lumen (usually most prominent at the point where the truncus brachiocephalicus crosses the trachea) during quiet spontaneous breathing is abnormal, the same could be seen in a normal trachea during coughing or with active expiratory effort. One study found that, in contrast to tracheomalacia, the cross sectional area of a normal trachea decreased < 25% from its maximum during spontaneous breathing, and the ratio between cartilage and pars membranacea was lower in tracheomalacia. However, this study used a clinical diagnosis of tracheobronchomalacia as the gold standard and analyzed only seven cases and eight controls, which makes it difficult to generalize the findings. Normal values from larger number of children without tracheobronchomalacia for the relative contribution of cartilage and pars membranacea to the tracheal circumference are clearly needed. Directly measuring the stability of children’s airways during bronchoscopy (e.g. transmural pressures and corresponding airway size) is impractical in clinical routine and normal values have not been established. Usually, the stability of the airway during bronchoscopy is determined visually as described above. However, this method is not without pitfalls for technical reasons: if the bronchoscope is large compared to the airway (e.g. in infants), it will increase airway resistance proximal to the area visualized. Therefore, dyspnoea and active expiration may ensue, leading to a false diagnosis of tracheobronchomalacia, or to inadvertent PEEP and expiratory distension of the airway (masking tracheobronchomalacia). It is therefore important to tailor sedation / anaesthesia exactly to assure quiet breathing with a sufficient tidal volume and flow to allow a confident diagnosis of this entity. However, once the diagnosis is ascertained, unnecessary therapies such as inhaled steroids or beta-mimetics can be stopped, and in severe cases surgical interventions such as aortotruncopexy may be considered. The diagnostic value of bronchoscopy in suspected chronic aspiration or reflux associated respiratory symptoms and wheeze is less clear. In infants, endoscopy (sometimes combined with oesophagoscopy) may be useful if aspiration is strongly suspected. If a lateral chest X-ray in the prone position with contrast filling of the esophagus has suggested an isolated tracheoeosophageal fistula or laryngeal aspiration, bronchoscopy is useful to thread a thin catheter through the fistula preoperatively to simplify its location, or to identify a laryngeal cleft. If reflux/aspiration is suspected, bronchoscopy can identify dorsal laryngitis and tracheobronchitis making it more likely that the wheeze may be caused by this mechanism. A trial with a proton pump inhibitor then usually clarifies its contribution to the clinical picture. Bronchoscopy and BAL analysis and bronchial biopsies A retrospective case series investigated 30 young children with recurrent wheeze poorly responsive to bronchodilators, who mostly had been tentatively labeled asthmatic, with bronchoscopy and BAL (3). While tracheomalacia was found in 12 and treated with aortopexy in one, the findings for the BAL culture and cytology are more difficult to interpret. Bacteria (11%) and viruses (33%) were isolated, and abnormal cell differential was reported in 41%. However, it was not reported how the treatment was varied depending on the BAL results and what change in clinical outcome was achieved on this basis. While BAL and the lipid laden macrophage index (LLM) have been advocated as a useful indicator for chronic aspiration, others have found considerable overlap with various bronchopulmonary disorders or normal children making the LLM almost useless. It appears that the lipids in the lipid laden macrophages represent endogenous lipids from inflammatory cells rather than exogenous aspirated material. One study investigated children < 18 months with recurrent wheeze which was poorly responsive to bronchodilators (3), and while four patients with proven reflux had an elevated LLM, two of these also had adenoviruses cultured from the airways, making the LLM findings difficult to interpret. Increases in this indicator have also been found after lipid infusions and in a child with veno-occlusive disease of the lung. One study (5) investigating 47 highly selected children with severe chronic wheeze found inflammation in BAL samples in 65%, and fat laden macrophages in 75%. A bronchial mucosal biopsy was also done in this series, and basement membrane thickening (29%) and eosinophilic inflammation (44%) were interpreted as characteristics for asthma. Still, it was not reported whether these interpretations and the therapeutic decisions resting on them resulted in better clinical management for the individual patients, and whether the diagnostic groups defined in the paper represent the different prognostic wheeze phenotypes mentioned above. The clinical utility and possible incremental diagnostic benefit from BAL and bronchial biopsy in this situation and for less severe wheeze remains an important field of research. Studies using sophisticated BAL cytology and inflammatory mediator measurements to investigate pathomechanisms of chronic or recurrent airway inflammation have shown various abnormalities in these patients. Unfortunately, at the moment it seems not yet possible to confidently predict whether a given patient has transient wheeze, wheeze with viral infection or incipient asthma from this kind of BAL derived measurements. Therefore, the routine use of BAL in wheeze outside of clinical studies seems not necessary. Special circumstances For patients who develop wheeze with certain preexisting conditions (such as bone marrow transplantation, lung transplantation or immunodeficiency) bronchoscopy, BAL and even transbronchial biopsy may be indicated to search for unexpected pathogens, graft versus host reactions or rejection. Some children who have undergone a Fontan-type repair of a cardiac defect may develop bronchial casts (plastic bronchitis). If these cause life threatening airway obstruction and do not react to conservative therapy such as withholding oral long chain fatty acids, attempts to dissolve the casts through urokinase inhalation etc., bronchoscopic removal of the obstructing casts may be life saving. Conclusions In our experience, a bronchoscopy is justified in children with severe or persistent chronic wheeze when careful investigations, as outlined above, have failed to arrive at a diagnosis and/or therapeutic trials have not improved symptoms, or if there is an unexplained worsening of symptoms. In many cases, a definite morphological diagnosis can be made and unnecessary therapy can be stopped. The addition of BAL and bronchial biopsy in order to better characterize the remaining cases is currently an important tool for research and may be indicated clinically in selected cases. References 1. de Blic J, Marchac V, Scheinmann P. Complications of flexible bronchoscopy in children: prospective study of 1,328 procedures. Eur Respir J. 2002;20:1271-6. 2. Nicolai T, Roncato S Fischer-Truestedt C, Reiter K. Prospective multicenter evaluation of the diagnostic yield and side effects of paediatric bronchoscopies. Eur Respir J 2005; 26: Suppl. 49, 438s 3. Schellhase DE, Fawcett DD, Schutze GE, Lensing SY, Tryka AF. Clinical utility of flexible bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage in young children with recurrent wheezing. J Pediatr 1998; 132:312-318. 4. Cakir E, Ersu RH, Uyan ZS, Oktem S, Karadag B, Yapar O, Pamukcu O, Karakoc F, Dagli E. Flexible bronchoscopy as a valuable tool in the evaluation of persistent wheezing in children. Int J Pediatr Otorhinolaryngol. 2009;73:1666-8. 5. Saglani S, Nicholson AG, Scallan M, Balfour-Lynn I, Rosenthal M, Payne DN, Bush A. Investigation of young children with severe recurrent wheeze: any clinical benefit? Eur Respir J. 2006;27:29-35.