Céli Dé

advertisement

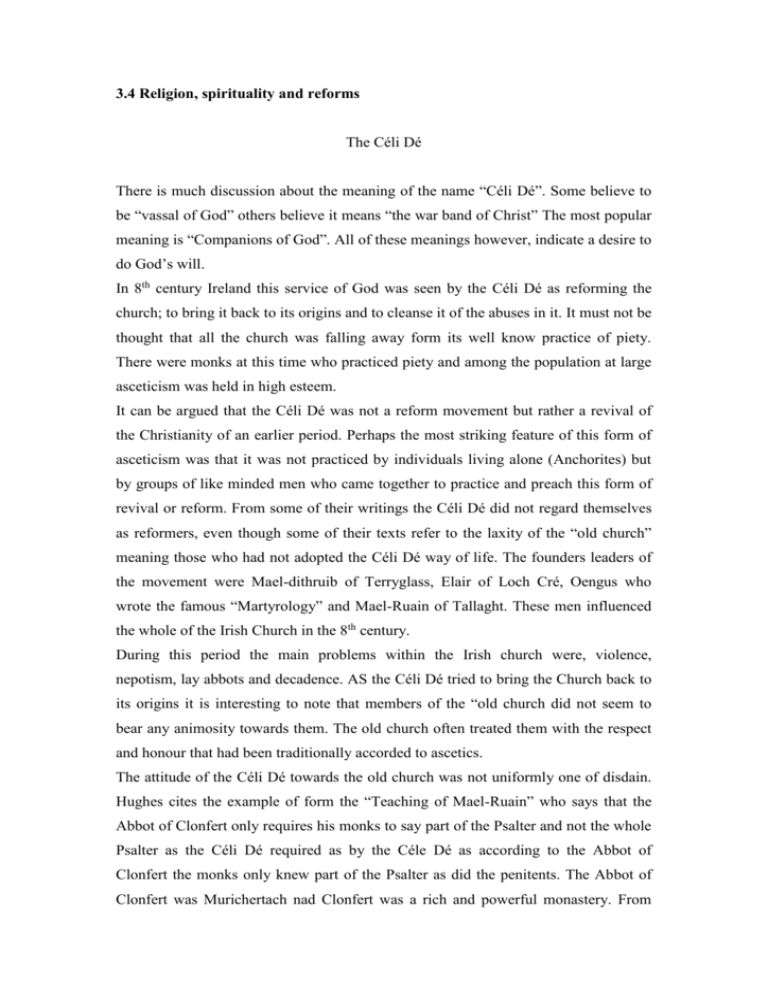

3.4 Religion, spirituality and reforms The Céli Dé There is much discussion about the meaning of the name “Céli Dé”. Some believe to be “vassal of God” others believe it means “the war band of Christ” The most popular meaning is “Companions of God”. All of these meanings however, indicate a desire to do God’s will. In 8th century Ireland this service of God was seen by the Céli Dé as reforming the church; to bring it back to its origins and to cleanse it of the abuses in it. It must not be thought that all the church was falling away form its well know practice of piety. There were monks at this time who practiced piety and among the population at large asceticism was held in high esteem. It can be argued that the Céli Dé was not a reform movement but rather a revival of the Christianity of an earlier period. Perhaps the most striking feature of this form of asceticism was that it was not practiced by individuals living alone (Anchorites) but by groups of like minded men who came together to practice and preach this form of revival or reform. From some of their writings the Céli Dé did not regard themselves as reformers, even though some of their texts refer to the laxity of the “old church” meaning those who had not adopted the Céli Dé way of life. The founders leaders of the movement were Mael-dithruib of Terryglass, Elair of Loch Cré, Oengus who wrote the famous “Martyrology” and Mael-Ruain of Tallaght. These men influenced the whole of the Irish Church in the 8th century. During this period the main problems within the Irish church were, violence, nepotism, lay abbots and decadence. AS the Céli Dé tried to bring the Church back to its origins it is interesting to note that members of the “old church did not seem to bear any animosity towards them. The old church often treated them with the respect and honour that had been traditionally accorded to ascetics. The attitude of the Céli Dé towards the old church was not uniformly one of disdain. Hughes cites the example of form the “Teaching of Mael-Ruain” who says that the Abbot of Clonfert only requires his monks to say part of the Psalter and not the whole Psalter as the Céli Dé required as by the Céle Dé as according to the Abbot of Clonfert the monks only knew part of the Psalter as did the penitents. The Abbot of Clonfert was Murichertach nad Clonfert was a rich and powerful monastery. From Mael-Ruain’s writings it appears that Muirchertach while not a member of the Celi Dé himself was sympathetic to their ideals. One important aspect of the Cele Dé was that had little to do with the laity. In fact they were know as the “clerics of the enclosure” in the “Rule of St. Carthage”. MaelRuain held that the monks should not become involved with worldly affairs but to concern themselves with spiritual maters The Céli Dé believed that the body was a source of sin. They held that the flesh must be subjugated. Women were also thought of as sources of sin. In the old church women did help in the work of the priest but this was banned under the reform. Women were not to be trusted and Mael Ruain spoke of women as mans 'guardian devil". (Life of Mael Ruain.) One of the practices of the Céli Dé was the shortening of penances. This was not done to alleviate but rather to encourage the practice of penance. It appears that the Céli Dé were reviving penitential practices of the early Irish church. These penances included "vigils of the Cross, vigils while standing in water, flagellation and total abstinence. Neither did Mael-Ruain allow secular music to be played. There was one sin that Mael-Ruain regarded as most serious and that was breaking one’s vow of chastity. Previously if a priest had sinned in this way he was received back into the church after a period of penance but under Mael-Ruain if a priest broke his vow of chastity he could no longer be a priest no matter what penance he did. Pilgrimage had been an integral part of the Celtic church life but Mael-Ruain forbade his monks to go on pilgrimage those who did go he regarded as deserters of the faith. The Céli Dé kept a very strict observance of Sunday. Sunday was to be dedicated totally to God. No work whatsoever might be done; all food preparation for Sunday was to be done on Saturday. No journey unless absolutely necessary was to be made unless it was to say Mass, administer Communion and to care for the sick. This is probably one of the features of the Céli Dé that was part of early Christian practice in Ireland. This strict observance of Sunday was something that had first appeared in continental Europe sometime before and was widely practiced. It is possibly that the Céli Dé was aware of this practice and introduced it in Ireland. Similar adoption of a continental practice was the encouragement of postulants and others to take Holy Orders and become and ordained priest. Many of the monks at the time were not in Holy Orders. During the Benedictine reforms in Europe this practice of ordained men becoming monks was wide spread. The Divine Office was said daily and throughout the night. It consisted of readings prayer and Psalms. Each Office was approximately three hours apart and in some monasteries continued throughout the night. Mass was also said and time was allotted for private prayer and study. The daily life of a Céli Dé monk was very disciplined. Every time the bell was rung for the Divine Office the monk said a “Gloria” and an “Our Father and went directly to the church. During his working hours the monk was expected to say the complete Psalter. At night between the Offices two monks kept vigil in the church reciting the Psalter. Number of Litanies and Martyrologies were written but these were for private use and to encourage the monk in his piety. The monks were also concerned with liturgy and the celebration of the Mass which might suggest that in other places these were not performed with due care and devotion. The Céli Dé did not affect the organisation of the monasteries so much as the life of the monks. However they did encourage young boys to become priests a was the way on continental European. There appears to have been a growth in the number of anchorites but these were mainly supported by the older church. A number of new stricter monasteries were founded of which Tallaght was the most important. However each house set its own standards and while there was communication between the houses of the Celi Dé this was on an informal basis. The Céli Dé tried to prevent the world entering into their lives and to live an ascetic life. They did create a way of making their reforms permanent and neither did they have the authority to deal with recalcitrant lay people. If a person went to a Céli Dé for confession and did not follow the monk’s advice there was little the mok could do about this except refuse to hear his confession the next time. Kathleen Hughes says that the root of the reforms was “the awareness of the presence of God” Student Work Research a modern day religious house with reference to the Divine Office and private prayer. What were the positive aspects of the Céli Dé movement? Were there ahy negative aspects? Are there any of the reforms of the Celi Dé being rediscovered in the church today?