comments from 2000 ap lit exam, question 1

advertisement

COMMENTS FROM 2000 AP LIT EXAM, QUESTION 1

Odysseus’s encounter with sirens versus Margaret Atwood’s poem “Siren Song”

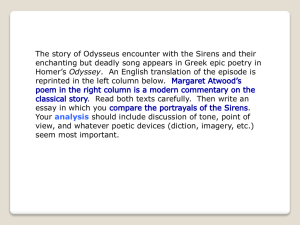

PROMPT: The story of Odysseus’ encounter with the Sirens and their enchanting but deadly song

appears in Greek epic poetry in Homer’s Odyssey. An English translation of the episode is reprinted

in the left column below. Margaret Atwood’s poem in the right column is a modern commentary on

the classical story. Read both texts carefully. Then write an essay in which you compare the

portrayals of the Sirens. Your analysis should include discussion of tone, point of view, and whatever

poetic devices (diction, imagery, etc.) seem most important.

GENERAL NOTES ON WHAT AP and PRE-AP WRITERS need to know

WRITE LEGIBLY. It’s hard to “reward” someone for brilliant ideas when you cannot decipher them.

By the time you’ve tried to piece the thought processes together, you’ve lost some of the possible flair.

Middle-sized handwriting is the easiest to read.

MAKE IT EASY on the reader. Don’t scratch out too much, write in the margins too much, or skip

spaces between lines. It’s okay to leave occasional gaps in your text in case you have time to go back

later to change an idea or add something; but make sure it’s clear. We have around 1000 essays to

cover in 7 work days, and every time we have to reread something, the points for clarity of expression

go down.

CHANGE PARAGRAPHS. One big glob of text lacks the signals needed to help the reader

understand your points.

USE PUNCTUATION AND TRANSITIONAL WORDS within the paragraphs to add clarity.

WRITE MORE THAN A PAGE on the question, regardless of handwriting. Even if the interpretation

is accurate, if you only write a page, you won’t have the supporting references from the text to score

more than a 4. Many readers immediately turn off if the response is SHORT.

LENGTH ALONE WON’T MAKE IT. Nothing is more bothersome than a weak paper that rambles

and repeats, indicating little or now PRE-PLANNING. The best it will receive is a low 3 or 4. (A few

students used rambling comments on other works of literature that had no bearing whatsoever on the

passages about sirens.)

STATE THE COMPLETE RESPONSE to the prompt’s question clearly in your INTRODUCTION.

Vague or ambiguous beginnings indicate a student who is bluffing his way into the paper, probably

one who didn’t stop to PLAN first. The higher papers prove they understand the prompt and respond

to it completely to avoid jumbled writing and lack of focus. A clear, effective start signals the scoring

person that “Here we might have a top paper!!” It helps considerably to have a THESIS

STATEMENT in the introduction.

AVOID LARDY INTRODUCTIONS—Get to the point! Some introductions are so goofy and wordy

that the readers take one look and skip them. (Some writers spent a great deal of unnecessary time

discussing other temptations besides sirens--tobacco or chocolate, for instance.) Even if you finally

answer the prompt somewhere later in your paper, you have already made the reader groan in distress!

AVOID REPETITIVE FORMULAIC CONCLUSIONS—I check intros and conclusions first before I

read the whole paper. If all I see is junk, usually the paper is low too.

EXPLAIN ALL QUOTES with commentary. Some of the weaker papers just string together quotes

without connecting them to the question. Using “supporting references” doesn’t mean randomly

tossing in any passage and enclosing it with quotation marks.

PLAN FIRST so you don’t repeat or ramble.

USE AP TERMS and advanced VOCABULARY. The best papers demonstrate impressive diction,

the reason the AP exams correlate so predictably with the SAT’s! An overuse of simple words

(“good,” “bad,” “nice,” etc.) signals lack of college preparedness and results in a lackluster paper.

BRIEF MANTRA:

PRE-PLAN TO STAY ON FOCUS.

ANSWER THE PROMPT IMMEDIATELY IN THE INTRO

SUPPORT WITH MANY EMBEDDED QUOTES TO PROVE YOUR POINTS.

WRITE AT LEAST 2 PAGES.

NO DEVICES WITHOUT A PURPOSE, NO QUOTES WITHOUT COMMENTARY

OMIT ALL LARD AND WORDINESS.

END WITH FINESSE!

EXAMPLES of STUDENT WRITING

(first draft, a few slight alterations):

SOME WAYS NOT TO START AN INTRODUCTORY PARAGRAPH:

--“It is always amazing to see such wonderful writing as blah blah blah…”

--“There are many works of literature that grasp the reader…”

--“ Temptations are everywhere. Some people are tempted by the cigarette companies who advertise on

television. Cigarettes are highly addictive. Some people are tempted by chocolate, and others are tempted

when their elderly mother calls them to take her to the hospital in the middle of the night.”

--“Both writers use diction to describe the Sirens.”

--“These authors paint pictures in the reader’s mind, causing the reader to understand the points.”

--“Homer and Atwood paint two different images of Sirens.” (WHAT are the images????)

SOME WAYS NOT TO CONCLUDE:

--“In conclusion, …”

--“After looking over both Homer’s passage and Atwood’s poem, a reader can now realize that both the

Sirens and Odysseus had a hard life to live.”

--“As we all can see, …”

--“When the reader reads these 2 works, …”

--“ Now it is clear in the reader’s mind that…”

EXAMPLES OF INTRODUCTIONS LEADING TO HIGH SCORES (Note sentence structure and

vocabulary variety):

--“These two passages describe an encounter with the same mythological creatures yet depict two totally

different views of the sirens. Homer’s passage conveys the Sirens as evil monsters whose diabolical

intentions are only thwarted by the intellect and leadership of a great hero. Margaret Atwood’s poem “Siren

Song,” however, portrays the Sirens as almost human and places the responsibility of a man’s death on his

innate stupidity and gullibility instead of on the Siren’s luring call.

--“Human curiosity has been a permanent force in our actions and our history; it has sent us on

explorations, quests for learning, and to the moon. Curiosity mixed with ambition or vanity, however, is a

much more negative and dangerous emotion. The Siren song, both in the Odyssey and in Atwood’s poem,

appeal to man’s curiosity and vanity, rendering man incapable of resistance. However, Homer and

Atwood, while writing of similarities in the songs, portray the Siren song very differently. Through

varying tone, diction, narration, and allusion, both Homer and Atwood are able to capture the appeal and

power of the Sirens.”

--“In a world where women have been denied their ability to work honestly and have been boxed into

complacent stereotypes, their only power—according to society—is this power to seduce through flattery

and sexuality. In Homer’s description of the Sirens’ song, Odysseus reacts with a masculine arrogance,

touting his own strength to escape seduction while lauding his crew for their loyalty. His voice is

somewhat heroic and grandiose as he relays a first-hand account of a dramatic brush with death, but

through his self-congratulating manner, he reveals this limited understanding and hubris emanating through

society that provokes Margaret Atwood to write her poem of protest “Siren’s Song.” Through allusion to

classical beliefs, she illuminates her own frustration at being confined to a stereotype, and through

repetition, she plays upon the unfounded pride of men like Odysseus.”

--“The Siren is the classic example of the feminine archetype known as the ‘seductress,’ the embodiment of

a beautiful creature who lures men to their deaths. It is fitting then that this archetype appears as one of the

many trials that befalls the legendary Odysseus in Homer’s epic The Odyssey. Here, the Sirens are depicted

as evil yet irresistible women. Their song brings even the strongest of heroes almost to the point of defeat.

Yet, in Margaret Atwood’s “Siren Song,” written from the point of view of the Siren herself, the reader is

given insight into the life of a Siren seductress. In the poem, the siren becomes more than just an

inescapable position in society.”

--“I suppose it’s far past time for a member of my gender (male) to step forward and say “I’m weakwilled.” We often get so caught up in faux-macho composure and a testosterone-induced haze that our

actions are not as clear and individualized as they should be; in short, we ascribe to a pack mentality. This

macho facade and overbearing demeanor obviously extends to our perceptions of the fairer sex. In classical

literature, it is ridiculously easy to find a ‘heroine’ that will violently throw herself at the ‘hero’ in hopes of

attaining love/ procreation/ a quick fling/ pleasant conversation. If a heroine or other female character

plays ‘hard to get,’ the male character (and, by extension, the reader) perceives her as a temptress or

seductive harpy, or perhaps as a Siren. Margaret Atwood’s “Siren Song” deals a firm, feminist slap in the

face to the misogynist undertones of the sirens in Homer’s Odyssey.”

SAMPLE OF EFFECTIVE CONCLUSIONS:

--“Homer and Margaret Atwood take the same mythological creatures and portray them in different ways.

Homer gives the classic view of evil monsters and destroyers of honorable man while Atwood flips the

picture upside down to show reluctant monsters with stupid victims who are not scared away by the

“beached skull.”

--“Ms. Atwood takes the one-dimensional ‘women=temptation’ viewpoint of Homer’s Odyssey and turns

the Sirens into far more cunning and developed personalities. They are still adept at luring men, but

Atwood’s Sirens are independent, crafty, passionate, creative, and cerebral, whereas Homer’s are little

more than giant pigeons with above-average singing talent. The former option, I find, is the only one for

which I would risk dashing myself on the rocks.”

--“The ultimate irony in comparing these two portrayals of the Sirens is that they are so similar. In

Homer’s traditional epic tale, the Siren captures her prey through the pure beauty of her song. While

Atwood’s different point of view and tone creates a more compassionate depiction than Homer’s passage,

the Siren is illustrated as playing on those very expectations. Her song is so successful because it lures

through what is supposed to be a ‘new’ side to her traditional portrayal.”

WORDS TO DESCRIBE HOMER’S TONE:

--Deadly attractive and irresistible tone

--Heightening aura of temptation, myth and

danger

--Frantic and rushed

--Magical and ecstatic

--Masculine achievement

--Imminent danger and trepidation

--Grave, fraught with danger

--Ranging from elation to desperation

--Appealing to pride and heroism

--Aura of irresistible danger

--“Honeyed voices” source of devilish

temptation

--Heroic sincerity

--Dramatic and agitated

--Tone of fear but fortitude to overcome it

--Triumph and confidence

--Opposition, struggle and pain

--Excruciating torment and agony

--Fearful panic

--Wonderful, aching to have more

--Soul-wrenching longing and curiosity

--Passionate

--Suspenseful and daring

--Masculine, heroic tone

WORDS USED TO DESCRIBE ATWOOD’S TONE

--Sedated and seductive

--Tone of enigmatic intimacy

--Calm, seductive, and enchanting

--Hypnotizing, lulling into sincerity

--Smugly condescending

--Full of false honesty

--Cynical yet irresistible

--More subtly alluring

--Conspiratorial

--Dripping with seduction and smoothness

--Sultry invitation and cunning deception

--Sweet-tongued persuasion

--Sadistic with a hypnotic rhythm

--Coquettish

--Self-effacing, mocking tone

--Hypnotic and repetitious, like the motions of

pocket watch, heavy and boring

--Blasé yet alluring

--Psychoanalytical

--Subtly satirical and devious

--Malcontent and flippant towards victims

EFFECTIVE EXPRESSIONS USED IN STUDENT PAPERS:

--The churning of the ocean and Odysseus’ passionate struggle against the “chafing” ropes convey his

struggle against temptation.

--The image of Odysseus’ strength, needing to be “bound…head and foot,” serves as a great contrast to his

moment of weakness in the presence of the Sirens with their “ravishing voices” and “honeyed words.”

--Odysseus glorifies the Sirens, describing them as something like a mysterious poison, an elixir killing the

victims moments after ingestion.

--When the Sirens make their lusty cries, “burst[ing] into their high, thrilling song,” Odysseus screams to

be set free, showing their great lure and prowess.

--Even though he struggles against its allure, [Homer’s] Siren song appeals to Odysseus’ sensuality and

masculinity and flatters his ego, as the Sirens call out to “famous Odysseus—Achaea’s pride and glory.”

--Odysseus gives the male point of view, showing that these ugly bird-women hybrids can attract the

greatest hero in history with the right tactics.

--[The Odyssey passage] depicts the stereotypical attempt to blame females for uncontrollable male urges.

.--[Atwood’s Siren] uses the conspiratorial tone of women who feign helplessness in order to attract and

undo men. The Siren posing as a distressed damsel actually has a smirk on her face.

--The Siren knows the fuel and the morbid implications of her task, and her haphazard view of death

characterizes her true evil…the words of Atwood’s Siren dominate the legions of men and prey on their

weaknesses.

--[Atwood’s Siren’s] whining and begging are all an enticing ruse to evoke pathos, as the speaker

conclusively states with smug satisfaction that her song “works every time,” thereby accurately portraying

her cunning method—to offer a desperate cry for help with an offer of knowledge.

--Atwood’s Siren, a femme fatale, is much less direct, destroying her victim by lulling him into a false

sense of complacency…assuring her victim of his singularly heroic qualities: only he is “unique.”

--Atwood’s Siren is more subtle, a mundane creature in a “bird suit” with “maniacs” as companions:

nothing is suspected until the trap already has snapped shut. Her simple statement that her ploy “works

every time” is almost like muttering “same old, same old” under her breath.

--Atwood’s Siren is [like] a disgruntled employee working at a fast-food job, doing a repetitive task day in

and day out, seeing only the predictable results.

--[Atwood’s Siren] is a luring, lulling machine, dripping with sweet-tongued persuasion. After she creates

a hypnotic rhythm by repeating the word “song” five times, she ends with an ironic, sadistic twist.

--[Atwood’s Siren] agrees to tell the secret of the song’s mystical powers in exchange for freedom from her

“bird suit,” a costume that obviously doesn’t relate to her real motives and personality.

--Atwood’s poem depicts the credulity and stupidity of men who fall for the enchantress trick yet again.

--Atwood’s Siren traps her prey by crying out for help and employing flattery, cooing like a damsel in

distress, to attract the sailors.

--[Atwood’s Siren] is initially coquettish and diminutive, but such behavior belies her true venomous

nature, as she is hell-bent on ensnaring a hapless male through self-effacement and witticism.

--[Atwood’s] seductive Siren knows the way to a man’s sexual side, and uses an alluring tone of a damsel

in distress to easily dupe the “men [who] leap overboard in squadrons” to get to her.

--Atwood’s Siren weaves a web of obligations with her melodic and smoothly flowing song.

OTHER TONE CONTRASTS between Homer and Atwood:

--Action-packed tension and desire versus a consummate actress luring men to their death.

--Anticipating and urgent versus taunting and deceitful.

--Menacing with a sense of impending disaster versus the personified tricky being behind the voice.

--Mad with passion versus sly and mysterious.

--Stifled by own will versus stifled by her station in life.

INTERESTING COMMENTS

--The urgent call so bravely avoided by Odysseus in the Odyssey seems trite when described by the siren

who “does not enjoy singing” it.

--Women lure men in with flattery, only to dissect and eat them.

--The Siren coos to her man with a distressed, sultry tone, describing her companions as “feathery

maniacs”—like a woman who has spent too much time with her girlfriends.

--Odysseus’ sirens would never “squat.”

--These sirens don’t enjoy singing as much as they enjoy watching men die.

--Odysseus’ tale shows the sirens to be girls with a bad reputation who can seduce any man into death if

there is no beeswax interference.

--The sirens are Eve-like, trying to lure an Adam-esque Odysseus into their lair and corrupt him with their

hypnotizing song.

--The words fall short on waxed ears.

--There is a certain temptress inside all females where, instinctively, they crave control and feed on the

weaknesses of others. I like the sirens!

--A good example of a beautiful voice singing a boring song and inspiring nothing is Placito Domingo

singing “La Macarena.”

--Atwood provides a first-hand account of how the call uses very humanistic facts to permeate its victims.

--The poem demonstrates the chance of being tricked by nothing more than Julia Roberts in a bird suit.

--The differences between Homer’s rendition of the Siren Song and Margaret Atwood’s poem are as vast as

the Caspian Sea.

COMMENTS TO AVOID

--This tone is so enjoyable because it is able to keep the reader interested all the way through.

--Diction is another needed device that an author cannot help to include in his/her passage.

--The reader is drawn in and kept by the tone, and it, most often, is the reason for the passage’s success.

--Homer and Atwood not only grabbed the language but juggled it, played with it, and then threw it at you.

--The word “shout” means to talk loud and have the sound carry. The sound carries the image of shouting.

--Odysseus has to tie himself down so he will be saved from being portrayed.

--The language throughout the poem could be improved. The reader feels nothing. Atwood did not

accomplish anything with her poem and should be ashamed of herself.

--“They flung themselves at the oars and rowed harder.” This small sentence shows the boat’s point of

view.

--One would think a man of Odysseus’ pride and reputation would be above such junior high influences—

always present peer pressure.

SAMPLES

HH

Greek epic poetry is collectively hailed for the never forgotten portrayal of fantasy and mysticism.

Held in the minds of great writers such as Homer, they are able to master the techniques that reel the

audience into a stream of mindless matter with which such writings would never be claimed interesting or

worthy. In comparing the Siren section of Homer’s Odyssey and Margaret Atwood’s responsive poem, we

must consider close analysis of tone, point of view, diction, and imagery.

As a man embarks on a journey, he is faced with many obstacles and temptations that he must

overcome. As Homer describes this journey, he sets the tone of the passage in the first sentence: “Now

with a sharp sword I sliced an ample wheel of beeswax down into pieces…” Instilling a sense of suspense

in the mind of the reader, we realize that the one of Odysseus can be observed as that of fear, terror, yet

with a minute glimpse of confidence. As he struggles to save his “comrades” from the “high, thrilling

song” of the Sirens, we grow more understanding of Odysseus’s despise towards the Sirens. The

“ravishing” sound of the Sirens’ voices as they sing allows the reader to envision his “heart inside [him

that] throbbed to listen longer.”

Turning to Margaret Atwood’s poem, one can only observe that by having taken a somewhat

satirical point of view, she has turned her poem into a very mockery of the Sirens’ song. Margaret implies

that the song, being as “irresistible” as it is, causes men to “leap overboard in squadrons.” One can only

imagine the terror of a ship of men as they flee to save their lives. Margaret portrays the speaker as being

one of the Sirens who doesn’t “enjoy singing this trio” although she knows it is “fatal” and “valuable.”

When the reader gets to the end of the poem, they learn that the song, as seen by Atwood, is a mere “cry for

help.” The tone is that of disappointment and somber as she finally concludes that the “boring” song “

works every time.”

When you compare the passage written by Homer to the poem that was written by Margaret

Atwood, you notice that there is a momentous amount of variability in tone, point of view, diction, and

imagery. The “honey voices pouring from [their] lips” caused a different reaction in both Odysseus and

Atwood. Not only does Margaret Atwood see the Siren song as something to take pride in, but at the same

time, she makes a mere joke of it by stating that it’s “boring.” In the eyes of “Achaea’s pride and glory,”

though, it is just a call to the innocent and oblivious sailors that pass by.

CC

Both Homer and Atwood portray the Sirens in a similar manner. Their mutually unique methods

share a common tone towards their subjects. Both authors portray to the readers the sirens as deceptive and

flattering.

Homer tells his story in first person through the eyes of Odysseus. His portrayal of the Sirens is

thus subjected to the views of Odysseus’ character. The tone of the passage is fearful and suspenseful. We

are shown the fear of both Odysseus and his crew. Any force which instills the desire to be bound to a

ship’s mast for fear of its seducing nature is indeed a frightful idea. The passage is given a hint of suspense

when we are made to wonder what will become of Odysseus and his crew. Will the crew disobey his

orders and untie him. Their absolute fear of the situation is shown again when “they flung themselves at

the oars, and rowed on harder.”

Homer shows the nature of the Sirens through their song. His diction shows how they flatter

Odysseus. They call to him, describing the traits he aspires to the most: those of the hero. They call

“famous Odysseus” and dub him “Achaea’s pride and glory,” and their song is “thrilling.” Who would not

be thrilled to be famous and all the rave in your homeland?

Atwood paints for us a similar portrait of the Sirens. She too writes in the first person, but she

takes the role of a Siren herself. By doing this, the poem becomes the Siren’s Song, making it aptly titled.

Atwood shows the Sirens’[ trickery by not showing the audience that the Siren is actually using its

charming song until it’s too late. She too flatters the listener with her diction. The word “you” is used

often as though to ask for “help.” She cries that “Only you” can help, “only you…” and flatters more by

saying “you are unique.” By making herself seem helpless, Atwood’s speaker seduces even more. The

audience is made to feel sorry for the Siren. She is not evil, just misunderstood. We should go to her and

help her. Therein lies her trickery. She uses her flattering diction to counter even her own negative

imagery (the fearful “beached skull” even we are made to ignore.)

Both authors portray the Sirens as fearful, yet seductive. To submit to their beautiful song is to

die, but who could resist? The mighty Odysseus even is not immune, and we the reader too are tricked,

despite how clever we are.

WWW

The Siren is the classical example of the feminine archetype known as the “seductress.” The siren

is the embodiment of a beautiful creature who lures men to their deaths, a femme fatale, if you will. It is

fitting then that this archetype appears as one of the many trials that befalls the legendary Odysseus in

homer’s The Odyssey. Here, the Sirens are depicted as evil yet irresistible women. Their song brings even

the strongest of heroes almost to the point of defeat. Yet, in Margaret Atwood’s “siren Song,” written from

the point of view of the Siren herself, the reader is given insight into the life of a Siren seductress. In this

poem, the Siren becomes more than just a challenge to overcome but rather the victim of an inescapable

position in society.

In Homer’s Odyssey the Sirens are presented as a contradiction: a dichotomy consisting of all that

is magically beautiful but also all things that are horrid and destructive. This concept is enforced by the

diction of the excerpt on the Sirens, full of such phrases as “thrilling song” and “honeyed voices,” set

against the images of a rough and restless sea with frothy “whitecaps.” Although this reproduction of

Homer’s Odyssey is merely a translation, there is evidence of the conflicting nature of the Sirens with the

euphony of words such as “Sirens sensed at once a shop” and the cacophony of words such as “Come

closer, famous Odysseus”! Clearly, the author views the Sirens and their song as something to be cherished

and simultaneously feared. This accounts for the sense of torment and recklessness in the narrator’s tone,

as with “the heart inside me throbbed to listen longer,” which is tempered by a sense of accomplishment by

the end of the passage. Odysseus had chosen the path of the “wiser man,” he has not been led astray by the

island temptresses and is therefore metaphorically loosened from “the bonds that lashed [him].” He is, in a

sense, more powerful than his temptations.

However, this sense of masculine conquest is absent in Atwood’s take on the song of the Sirens.

Here, in the feminine account of the daily life of Sirens, Atwood weaves a type of seduction for her readers

and gives depth to the “picturesque and mythical” creature. Atwood opens with the stereotypical concept

of the Siren. As in the tale of Odysseus, the Sirens possess the “song that is irresistible.” Once again the

reader is presented with a diction that makes use of the duality of the Sirens, as is seen with the euphonic

phrase “the song that forces men” set against the harsh image of the “beached skull.” But then, at line 12,

Atwood shatters the façade of the beautiful Siren who has men literally at her feet by showing the reader

the reality. The life of a Siren is, in fact, dull, explains Atwood’s Siren, full of constricting “bird suits” and

surrounded by “feathery maniacs.” This life is not “mystical,” it is an obligation, a job. This humdrum

tone becomes more and more panicked until it reaches the apex of “Help me! Only you can.” The reader

feels all of a sudden compelled to save the siren from her daily routine. This is, of course, Atwood’s

intention. She wants her readers to be drawn in by the siren, almost to the point of madness, just as

Odysseus almost falls prey to her song. And yet, the readers soon become victims themselves.

After an abrupt end-stopped line between the words “unique’ and “at last,” Atwood remarks

matter-of-factly that the song has once again claimed a victim. The picture she has painted of a helpless

woman trapped in a “boring life” reveals another facet. The Siren, like so many women, has been

subordinated by an inescapable obligation, but she has power all her own. As boring as her life is, she still

has the power to claim victims. Atwood’s Siren is not the romanticized evil seductress of The Odyssey and

yet she is an example of a woman who can exhibit power while still living a fixed position that she was

assigned by society.

KKK

Homer and Margaret Atwood have similar views of the Sirens. They both feel that these creatures

have intriguing but deadly voices. These voices call to every passerby and are irresistible to anyone that

hears it.

In Homer’s Odyssey, the encounter with the Sirens is being told from Odysseus’ point of view.

He is the only one on the ship that can hear these mythical creatures voices because he has put wax in his

crews ears. Odysseus, however, had his crew tie him to the ship’s mast, so he could not jump overboard in

response to the beautiful singing. His point of view gives the audience a feel for the power of the Siren’s

voices. He said their voices made “the heart inside me throb.” This intense yearning a desire made him

attempt to be free of the ropes, but his crew hurried to “bind me [him] faster with rope.” Atwood’s “Siren

Song” is told from the viewpoint of a Siren. The Siren knows the power of it’s voice; knows that “the

song…forces men to leap overboard in squadrons,” despite the fact that one can see “the beached skull.”

The Siren viewpoint is that they are using their voices to bring them food. They know that no living man

that hears their voice and their sad tale will be able to resist them. The Siren says the song is “a cry for

help,” when that is only being said to make the sailors feel pity. The siren is honesty when she says that the

song is “{fatal and valuable.” She is using the song to bring herself food, so it is valuable to her survival,

but fatal to those who hear it. The viewpoint of both Odysseus and the Siren show how devious the Sirens

are.

The tone in the Odyssey changes. At first there is the feeling of impending doom which is

followed by excitement when the boat was passing the Siren’s island. The tone at the end of the passage is

one of relief that the crew has made it safely past the island. Odysseus sets a tone of fear and impending

disaster while he is working to seal off his crew’s ears. He is working hard and fast and the audience feels

that something is about to happen. This is followed by excitement and anger as the ship approaches the

siren’s island. Odysseus grows excited and anxious when he hears the “honeyed voices,” but his quickly

turns to anger when he discovers that he cannot go to the voices because he is tied up. The tone at the end

of the passage is one of relief. The crew quickly removes the wax and unties their captain once they have

passed the island because they are safe for the vicious Sirens. The tone of Atwood’s poem is one of pity.

She is attempting to make the reader feel sorry for the sirens because no one can learn their song and live.

There is also a sense of pity in the actual words of the sirens. They want the sailors to feel sorry for the, so

the sailors will come to the island. Building up the pity, however, reveals the truth about the sirens; that

they are laying a trap for the innocent sailors.

Homer uses extensive imagery in this passage from The Odyssey. When Odysseus is softening

the beeswax, he uses the word kneading. This is visual imagery for the reader because bread dough is also

kneaded to soften it. After he seals off his crews ears, Odysseus has them tie him to the ship’s mast. By

using the phrase “bound hand and foot” and saying that the ropes “lashed [him] to the mast,” the audience

can realize that he is incapable of moving. When the Sirens begin to sing, Odysseus says their voices are

singing a “high, thrilling song.” The audience would realize that this was the kind of song that would be

easier to stop and listen to or sing along with than to walk on past it. The sirens also say that they have

“honeyed voices.” Honey is a sticky substance, so by using honey to describe their voices, the sirens are

saying that they use their voices to get the sailors stuck on them. Atwood is not as vivid in her imagery, but

it is still present. She uses “picturesque and mythical” to describe the sirens. In mythology, Sirens are

beautiful creatures, but since they are part bird, part woman, they truly are mythological. The words fatal

and valuable are used to describe the song of the sirens. It is both, valuable to the sirens, fatal to the sirens.

The point of view, tone, and imagery in this poem and passage provide a good comparison of the

mythological creatures. The Sirens are described from different point of views with a different attitude, but

the end result is the same: They are vicious creatures.

B

Homer and Atwood present the complexity of the myth of the Sirens through different points of

view, with different tones, and telling imagery. Homer tells the story of a man clever enough to hear the

siren’s song and not lose his life, while Atwood is a siren, a predator, waiting to trick men onto her island.

The tones of the passages are quite different. In both works, however, trickery and cleverness is

used. Odysseus escapes with his life, and the Siren wins, saying “Alas it is a boring song but it works

every time.” The tone in Homer’s passage is strong and powerful. “Now with a sharp sword…Helios’

burning rays…ship was racing past,” are phrases used to illustrate this tone. However, as Homer’s tone has

masculine qualities, Atwood’s has feminine ones. Her tone is crafty, then pleading. “Come closer…help

me! Only you, only you can,” the siren screams, pleading for attention. These two passages are like two

halves of a whole. Odysseus is prey, trying frantically to escape death, while the siren is a carnivorous

predator, singing for her supper. The tempo of the two passages is also quite different. Homer’s is quicker,

like a scurrying animal, while Atwood’s is deliberate. Atwood even uses punctuation to her advantage in

the last three stanzas. The last line of each stanza is broken, forcing the reader’s eye to the next stanza

without realizing the trickery. In the same way the Sirens lure men into their clutches. Homer splits his

passage into three sections according to the crew’s state: At first, they are sailing, then preparing, and

finally escaping.

The imagery in both passages is also quite different and reveling. Homer’s words are masculine,

powerful, and battle ready. He uses words like “sharp”, “strength,” “strong hands,” “churned,” “racing,”

“sharp sword.” The imagery is that of a man who is not only sailing by the sirens, but going to war with

them. Homer describes the Sirens’ song as “ravishing,” “high,” “thrilling,” and “urgent.” Their voices

make Odysseus’ heart throb, and there almost is a sense of sensuality taken from this imagery. Atwood’s

imagery is far from masculine and less sexual. The words “bird suit” and “squatting” almost give the

image of a ridiculous situation. However, “feathery maniacs” and “fatal and valuable” give off a more

serious image and tone. The imagery makes the reader identify and feel pity for this poor Siren, for she

hates what she is. By the end of her pleading, the reader has been sucked in, like the men who “leap

overboard in squadrons” mentioned in the first stanza. The poem begins seductively menacing, then

becomes almost whiny and innocent, and finally ends with the same grave and clever (fatal) tone.

These two passages each sing the song of opposing sides, yet they have much in common. They

both use trickery to escape or catch their kill, and they both are confident in their abilities except for equal

moments of weakness (Odysseus begging his men to untie him, Siren not “enjoying it…I don’t enjoy

singing) in both passages. Yet the two songs are the natural songs of an animal and its hunter.

L

The story of Odysseus’ encounter with the Sirens and their enchanting but deadly song appears in

Greek epic poetry in Homer’s odyssey. Over the years there have been various reproductions and

translations of this classical story. Margaret Atwood’s poem provides us with a new perspective about the

Sirens. Moreover, by analyzing both texts, I am able to compare the portrayals of the Sirens.

First of all, these two texts are written in different points of view. The excerpt from Homer’s

odyssey is written through Odysseus’s point of view. However, Margaret Atwood’s “Siren Song” is

written through the point of view of one of the Sirens. We are able to have two different perspectives on

this encounter because of the different points of view. Furthermore, both excerpts have a different tone. In

Homer’s Odyssey there is a feeling of fear and apprehension among the crew members aboard the ship.

They do not know what will happen as they get closer to the Sirens. Will they be able to make it alive?

The “Siren Song” on the other hand, conveys a calm and relaxed attitude. The Sirens also feel sad because

they are misunderstood by the humans. Towards the end of the poem, the Sirens are also mocking at those

that they have trapped with their enchanting songs. There is also a difference in their structure. Homer’s

Odyssey is written in a paragraph form. The “Siren Song” however, is written in stanzas.

In conclusion, by reading both excerpts about the Sirens we are able to experience two different

perspectives of this classical story. First of all, we can note that both texts are written in different points of

view. They convey different tones. Moreover, they are also structured differently. Even though they have

their differences, they are still extraordinary works of literature.

Y

The two portrayals of the Sirens between the story of Odysseus’ notorious encounter and Margaret

Atwood’s vivid poem gives two unique interpretations that somehow conjure up a clearer picture for the

reader. The different point of views, tone, imagery, style, diction, and genre compliment Homer’s and

Atwood’s work brilliantly.

Using Homer’s epic tale to relive Odysseus’ encounter with the sly Sirens, this first person point

of view allows the audience to experience the expectation and preparation of a one on three confrontation

with the three mythical characters. The shackling of Odysseus and the beeswax that he had prepared as ear

plugs for his men so that the Siren’s song could not affect them show how dangerously deadly the Sirens

are. The images used get across the picture of a strong, heroic man who is ready for battle against fate; the

myth of a supernatural creature who causes even the strongest crew to take the bait of the sweet Sirens’

song and see if he will be the special case to make it past alive.

Atwood uses her modern commentary to view the Sirens’ perspective. Instead of an actual human

critiquing the Sirens, as in The Odyssey, it is the talked about Sirens who have the opportunity to retell

their side of the story. The imagery is beautiful and along with tone, the Sirens send a message first of

intrigue and fascination to learn more about the song, amazement at its power that allows men “to leap

overboard in squadrons even though they see the beached skull,” and the humanistic character that makes a

person take on a challenge to find out the Siren’s secret “because anyone who has heard it is dead, and the

others can’t remember.” By playing on the audience’s emotions from sympathy for being stuck in a

monstrous body (a “bird suit”) and attached to two morons for a fatefull remainder of their lives, to

persuading and then downright crying for them to help her, the audience/reader is transformed to the sea

and captivated into the Siren’s woeful song. Even more so than the Odyssey version, where the Sirens tried

to lure odysseus who was strictly tied down, Atwood wants her readers to believe that they are surprised by

the appearance of the Siren and so persuaded by their act, that the last “only you can [help me], you are

unique,” is the last use of trickery needed to win another victory for the Sirens. The repetition of “the

song,” “this song,” “I don’t enjoy” all help add to the mystery and intrigue of finally giving in to the Sirens.

And the irony at the end of the Sirens compared with the other version, adds a great twist that the sly Sirens

knew what they were doing all along!

So free verse in the “Siren Song” and the epic which was the Odyssey, two completely differently

types of genre, two different points of view and even having more repetition and imagery and seduction in

“Siren,” they are still complimentary to each other.

XXX

Greek mythology depicts the Sirens as creatures of mystery and death—the power of women and

their appealing aspects taking complete control over men’s minds. The Sirens’ voices encompass such

beauty that no man is able to resist their song, and entire crews rush toward their death propelled by

mythical notes of bliss. In Homer’s Odyssey the Sirens inhabit their island as creatures—monsters

possessing the power of irresistibility, representing the seductive strength given to women. The idea of

feminine qualities so perfect and appealing that they render men powerless is a common theme in ancient

Greek mythology. A war is fought over Troy because of a woman, Helen. Women and goddesses are

given beauty and splendor beyond compare, empowering them through their physical qualities. The

strength of these mythological characters lies in their appearance, their voices, but they are not given the

intellect or strength of action possessed by Greek men. The heart of the differences between the two

passages is found in their depiction of women, in their source of strength and their relation to men.

In the passage from the Odyssey, Odysseus faces the daunting task of navigating past the Sirens,

whom no man can resist. But, in the tradition of Greek characters, Odysseus is able to triumph over the

Sirens through physical strength and superior intellect. Odysseus uses a man’s technique of planning and

taking action, plugging his crew’s ears and binding himself to the mast. Thus, he overcomes the temptation

of the Sirens with his mind and strength in the traditional role of Greek characters. This is the epitome of a

society in which women have power over men through their femininity but do not have power to rule or

act.

In contrast, the passage from Margaret Atwood, “Siren Song,” examines the situation from a

modern perspective, from the woman’s (the Siren) point of view. In the language of the poem, the verse

begins that “this is the song everyone would like to learn,” suggesting the mysteriousness of the Sirens, and

of women, and their control of situations and use of knowledge to create desire. As the passage progresses,

the tone is one of lamentation, as in line 10 the author switches to reveal her desire to be free of her “bird

suit,” her role as temptress on the island. In lines 4-9, the poet speaks of her power and seduction to cause

men to swim toward their death, but then the tone shifts, and the reader discovers her desire to be free of

the island and the “two feathery maniacs.” She is tired of squatting “looking picturesque and mythical.”

This is the voice of the modern woman, seeking liberation from the stereotypes of appearance and beauty.

In line 19 the Siren addresses the reader, baiting him in with a promise of sharing her secret “only to you.”

The poet pleads to the reader for help, for only he can free her from the constraint of her role as seductress.

Suddenly, in line 25, the poem shifts again, and the reader realizes in listening to the author’s

pleas he has come too close and has been devoured. The closing phrase “It is a boring song, but it works

every time” reveals the truth that the poet has switched roles from tempting as a woman to using her

intellect and drawing the unsuspecting sailor in. The final line places the woman liberated above the man

as not just a physical object but one capable of reasoning and acting to control him. Thus, this is the

modern picture of a woman’s place and power, shown through the author’s tone and point of view,

contrasted with the traditional Greek role of the Siren as a being capable of control through her beautiful

voice.

SAMPLE SCORES at reading

GGG—9

XX—5

UU—3

CC—7

OO—1

HHH—4

B—8

Shows shifts

A—9

KKK—5, going up. Lacks coherence and organization, repeats—but does TRY to analyze.

FF—7

VV—3

LL—4

WWW—9

W—7

JJ—4

T—8

EE—6

S—4

FFF—2

II—6

SSS—9

HH—4

DD—7

NNN—1

F—4

UUU—8

PP—4

M—6

DDD—4

Too much lard

Misinterpretation, confusing

Plodding but elegant, more finesse in style than most papers

Shows some analysis

No analysis

Genius, implied point of view and tone

Meager, lack of support

Unconvincing

A “C” paper at best

Too short

Grammar errors detract from higher score

Inadequate development, partial analysis, misinterpretation

USED here:

HH—4 Meager, lack of support, fishing with lard but never really connecting

CC—7 Compact and savvy but clumsy language; too brief for an 8

WWW—9

KKK—5 Lacks coherence and organization, repeats—but does TRY to analyze.

B—8

Shows shifts clearly, not quite a 9

L—3

No depth, a weak paraphrase

Y—6

Some awkward places, grammatical inaccuracies; too repetitious for a 7

XXX 9