GEORGE ELIOT (1819

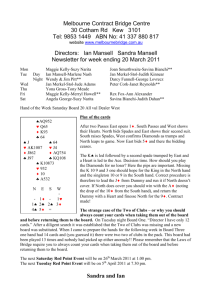

advertisement