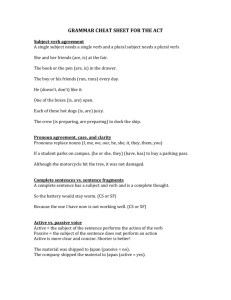

The Teachers` Reference to KISS Grammar Constructions, Codes

The Teachers’ Reference to KISS Grammar

Constructions,

Codes, and Color Keys

Idyll:

Family from

Antiquity

(1860) by

William-

Adolphe

Bouguereau

(1825-1905)

I I I n t t t r r o d u c t t t i i i o n

As you may know, KISS exercises are taken (or adapted) from sentences in real texts. Their “Analysis Keys” explain every word in every sentence—including those words the function of which the students are not yet expected to understand. Thus the keys have “Notes.” Originally, the exercises were all on-line, and the “Notes” included links to the explanatory material. When users asked for printable workbooks and analysis keys, things became more complicated. Linking the MS Word documents to the instructional material became more difficult and time-consuming. I dropped the links.

This document is meant to supply the missing materials. It explains not only the codes and color keys, but also gives brief examples of the relevant constructions. In a sense, it is a crash course in the “what” of KISS Grammar—what concepts and constructions will be taught. Learning to identify them in real texts and learning why doing so is important will take a fair amount of practice. Much of this document was simply taken from the instructional materials or the notes for teachers. Please note that this document does not explain any of the exercises on style (sentence-combining, etc.), logic, or writing in the KISS design. It does explain some of the punctuation exercises.

Level 1.2 Adding Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Adverbs, and Phrases ...................... 5

Level 1.4 Coordinating Conjunctions, Compounds, and Style ..................................... 5

KISS Level Two – Complexities of Prepositional Phrases and S/V/C Patterns .................. 6

Level 2.1.5 Phrasal Verbs (Preposition? Or Part of the Verb?) .................................... 7

Level 2.1.7 The KISS Perspective on the Subjunctive Mood ...................................... 8

Level 2.2.1 The “To” Problem and Verbs as Objects of Prepositions .......................... 8

Level 2.2.4 Advanced Questions about Prepositional Phrases ................................... 10

Level 3.1.1 Compound Main Clauses (Punctuation and Logic) ................................. 11

Level 3.1.3 Embedded Clauses and the Analytical Process ....................................... 14

Level 5.7 Passive Voice and Retained Complements (P) , (RDO) , (RPN) , (RPA) .................. 24

Level 6 Advanced and Additional Exercises ............................................... 29

Level 6.3 Style—Sentence-Combining and De-Combining .......................................... 30

Level 6.5 Statistical Stylistics and Advanced Analytical Questions .............................. 30

Level 6.8 Mixed Review and Additional Passages for Analysis .................................... 31

I I I m p o r r t t t a n t t t K I I I S S C o n c e e p t t t s s s

Compounding—Coordinating Conjunctions

Whereas most grammar texts explain compounding in multiple places (compound subjects; compound verbs, compound clauses, etc.), KISS treats compounding as a concept. Any identical parts of speech (such as adjective and adjective) or any construction can be compounded, usually by using “ and ,” “ or ,” or “ but

”). The conjunctions are coded orange.

Ellipsis—The Omission of Understood Words

The answer keys indicate words that are ellipsed by placing them between asterisks—* You* Close the door. This is a simple example, but as you will see in the notes, KISS eliminates some traditional, confusing terms by using the concept of ellipsis.

(Some linguists call it “reduction.”) For example, in the sentence “They painted the floor

white,” KISS explains “floor white” as an ellipsed infinitive construction—“floor *to be* white.” The infinitive phrase then functions as the direct object of “painted.”

Embedding—One Construction in the “Bed” of Another

Our sentences grow as we learn to place one simple sentence into the bed of another. The child’s “My dog is small” and “It is brown” become “My dog is small and brown” as the child learns to ellipse (reduce) “It is” from the second sentence and embed

“brown” in the first. In essence, the majority of words in a sentence are embedded in it, but there is no reason to discuss how. The important cases involve prepositional phrases and subordinate clauses. They are discussed below.

Modification and “Chunking”

Adjectives, adverbs, most prepositional phrases, and many clauses modify a noun, pronoun or verb. This is a standard idea in most grammar textbooks. As modifiers, they affect the meaning of the words or constructions that they modify. But because KISS is interested in how sentences work, it adds another perspective—“ chunking

.” The KISS psycholinguistic model describes how our brains connect the words to each other in order to derive their meaning. Psycholinguists call this “chunking.” We chunk individual words into phrases, phrases into longer phrases, then into clauses, and then into sentences. This model underlies most of KISS. Among other things, it suggests why punctuation works as it does. Put differently, what we should be trying to teach students is a model of how our brains work to process language.

T h e e F i i i v e e K I I I S S L e e v e l l l s s s

The following is organized by the original five KISS levels. I have included explanations on almost all the KISS Levels, but I cannot give the full reasoning behind them here. For more about any of them, see “The Master Collection of KISS Exercises” on the KISS website.

KISS Level One – The Basic Sentence Pattern

Level 1.1 Subjects and Verbs.

Subjects are in green and underlined once; verbs are in blue and underlined twice”

Her appetite

grew

amazingly.

Level 1.2 Adding Nouns, Pronouns, Adjectives, Adverbs, and Phrases

A djectives are in green and adverbs in blue . Both are in smaller type. When students are focusing on adjectives and adverbs, they are asked to draw an arrow from each to the word it modifies. They are not asked to do that in most exercises because the arrows simply add clutter.

Level 1.3 Adding Complements

(PA, PN, IO, DO)

In KISS, a “complement” is a word (or construction) that answers the question

“whom?” or “what?” after a verb. Several users noted that students had problems with the two-step directions for identifying the types of complements, so in some early exercises students are directed to simply write “C” over the words that function as complements. In the analysis keys, however, the specific types of complements are indicated in brown:

The story of Rip Van Winkle

may seem incredible

(PA) to many.

I

give it

(IO) my full

belief

(DO) .

Level 1.4 Coordinating Conjunctions, Compounds, and Style

Level 1.5 Adding Simple Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional Phrases are identified {by braces} , primarily because braces are rarely found in real texts, whereas parentheses are. Phrases that function as adjectives are in green; those that function as adverbs are in blue. Adjectives, adverbs and coordinating conjunctions within prepositional phrases are in the color of the phrase because we are more interested in the functions of phrases than in the functions of individual words.

Other constructions that appear within these phrases are explained in the notes.

Level 1.6 Pronouns (Case), Number, and Tense

Level 1.7 Focus on Punctuation and Capitalization

Level 1.8 Vocabulary and Logic

KISS Level Two – Complexities of Prepositional Phrases and S/V/C Patterns

These are normally ignored in grammar textbooks.

L e e v e e l l l 2 .

.

.

1 T h e e C o m p l l l e e x i i i t t t i i i e e s s s o f f f S / / / V / / / C P a t t t t t t e e r r n s s s

Level 2.1.1 Understood “You”

Level 2.1.2 Varied Positions in the S/V/C Pattern

Level 2.1.3 Expletives (Optional)

[Exp]

Traditional grammars explain “There” is sentences such as “There

are

five men here” as an “expletive” and describe “men” as the subject. Because many people are familiar with this explanation, KISS accepts it, but it does violate the “KISS” premise by adding an unneeded concept. In KISS, the preferred explanation is to consider “There” as the subject and “men” as a predicate noun—“ There

are

five

men

(PN) here.”

Level 2.1.4 Palimpsest Patterns

In ancient times, clay tablets were often erased by rubbing them fairly smooth and then new writing was put over the old. These tablets are called “palimpsests”—one text is written over another. To my knowledge, the concept of the “palimpsest” pattern is unique to KISS Grammar. Once one has spent a little time analyzing randomly selected texts, however, the concept becomes somewhat obvious.

As noted elsewhere in KISS, the traditional “transitive,” “intransitive,” and

“linking” verbs are not very helpful, especially because “linking” verbs are usually presented in a short, incomplete list that students are expected to memorize and then forget. They can’t use the list effectively because it is incomplete.

One of my favorite examples of a palimpsest is from Mary Renault’s The King

Must Die :

As I rode under the gate-tower, the gates

groaned open

(PA) , and the watchman blew his horn.

In palimpsests, another verb is “written over” a form of “be” or “become.” In this case,

“groaned” is written over “became.” The following are all from At the Back of the North

Wind by George Macdonald:

Even the ground

smelled sweet

(PA) .

They

had been sitting silent

(PA) for a long time.

The stars

were

still

shining clear

(PA) and

cold

(PA) overhead.

She

sat motionless

(PA) with drooping head and did not move nor speak.

But the primrose

lay still

(PA) in the green hollow.

And indeed, Diamond

felt

very

strange

(PA) and

weak

(PA) .

As the preceding examples suggest, in most cases, palimpsest patterns involve a verb written over an S/V/PA pattern, but sometimes the pattern has a predicate noun. The following example is from The Dark Frigate by Charles Boardman Hawes:

The other ship, in which he now

sat

a

prisoner

(PN) , was like some great tiger.

In KISS, there is no need for students to try to memorize an incomplete list of linking verbs.

Level 2.1.5 Phrasal Verbs (Preposition? Or Part of the Verb?)

My favorite example of this little problem is “Put on your thinking cap!” The purpose of this section is to stop students from unthinkingly marking “on your thinking cap” as a prepositional phrase. Instructions? Pay attention to the meaning. It means “Put your thinking cap on your head.” With phrasal verbs, the “preposition” part can be explained either as an adverb or are part of the finite verb phrase.

Level 2.1.6 Distinguishing Finite Verbs from Verbals

Verbals are verbs that function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs. The purpose of this section is to stop students from underlining verbal twice. (Every verb functions either

as a “finite” verb—a verb that is the core of a clause, or as a verbal.) To do this, KISS gives students three tests:

The Noun Test

A verb that functions as a noun (a subject, a complement, or the object of a preposition) is not a finite verb. (Do not underline it twice.)

The “To” Test

A finite verb phrase cannot begin with “to.” Thus in “Bob went to his room to do his homework,” “to do” is not a finite verb. (Do not underline it twice.)

The Sentence Test

The last way to distinguish finite verbs from verbals is the simple sentence test. If you are not sure about whether or not to underline a verb twice:

1. Find the subject of that verb.

2. Make a simple sentence using that subject and verb—without adding any words, and without changing the form or meaning of the verb.

3. If the sentence does not seem to be an acceptable sentence, the verb is not finite.

Level 2.1.7 The KISS Perspective on the Subjunctive Mood

The subjunctive mood poses very complicated questions, but the primary purpose of this section is to make sure that students (and teachers) do not consider “were” in “If he

were

here, he would not do that,” as a subject/verb agreement error. The section also discusses the possible meanings of subjunctives and introduces other words that form subjunctives:

Be

he

devil

(PN) or

angel

(PN) , she won't like him.

Had

we but

world

(DO) enough, and

time

(DO) . . . .

L e e v e e l l l 2 .

.

.

2 T h e e C o m p l l l e e x i i i t t t i i i e e s s s o f f f P r r e e p o s s s i i i t t t i i i o n a l l l P h r r a s s s e e s s s

Level 2.2.1 The “To” Problem and Verbs as Objects of Prepositions

Little words cause the biggest problems. If we wish to enable students to analyze and discuss real texts, students need to distinguish “to” as a preposition from “to” as the

sign of an infinitive (a verbal).Here again the focus is on enabling students to correctly identify the prepositional phrases—and not mark infinitives as prepositional phrases. The section does contain one exercise on verbs as objects in prepositional phrases, as in “I'll have you arrested {for leaving your horses}.” There is also a spelling exercise on “to,”

“too,” and “two.”

Level 2.2.2 Preposition or Subordinate Conjunction?

Once they get to prepositional phrases, students are directed to always find the prepositional phrases in sentences first. As a result, some students will mark “Before the sun” as a prepositional phrase in:

Before the sun rises, the birds begin to chirp.

To help students avoid this error at this point in their work, the instructional material informs students that “if whatever answers the question “Whom or what?” after what looks like a preposition is a sentence, it is not a prepositional phrase. It then states:

“(They are subordinate clauses, but you do not need to remember that now. Just remember not to put parentheses around them.)”

Level 2.2.3 Embedded Prepositional Phrases

Prepositional phrases are often embedded in other prepositional phrases. Because

KISS focuses on how every word connects to another word in the sentence until every word (except interjections) connects to a main subject/verb pattern, the KISS keys note embedding by underlining the embedded phrase and the phrase in which it is embedded.

In the following sentence from A Tale of Two Cities

, the phrase “in Soho” modifies

“corner” which itself is in a prepositional phrase.

Never

did

the sun

go

down {with a brighter glory} {on the quiet corner} {in Soho} .

In some sentences, compounded objects of prepositions are separated from each other by constructions that modify the first. In these cases, students are told that they can writing the preposition in, enclosed in asterisks:

We

came

{to a pretty, low house} , {with a lawn and shrubbery} {at the front} and

{*with* a drive} {up to the door} .

Level 2.2.4 Advanced Questions about Prepositional Phrases

This section reinforces the section on verbals as objects of prepositions. It also previews clauses as objects of prepositions. Among other fine points, it explains that some prepositions have ellipsed objects, as in “They had done this many times before .”

L e e v e e l l l 2 .

.

.

3 A d d i i i n g T h r r e e e e L e e v e e l l l F i i i v e e C o n s s s t t t r r u c c t t t i i i o n s s s

When KISS was taught to college students in a single semester, these three constructions were put in Level Five—the last to be taught, last simply because one need not know these in order to understand clauses and verbals. When KISS is spread across several years, they can be introduced much earlier.

Noun Used as an Adverb

[NuA]

Nouns are frequently used as adverbs:

Then everyone

went

home

[NuA] again .

I

was myself

(PN) last night

[NuA]

. [From Rip Van Winkle ]

He

is

five years

[NuA]

old

(PA) .

Simple Interjection

[Inj]

KISS expands the concept of “interjection.” (See below.) Here, students are introduced to the simple ones, such as “Ah [Inj]

, it '

s

a beautiful

day

(PN) ! Like some grammar texts, KISS includes as interjections prepositional phrases that express a writer’s (or speaker’s) attitude toward the sentence—“ He

was

, {in my opinion}

[Inj]

,

brave

(PA) .”

Direct Address

[DirA]

Direct Address is essentially a special type of interjection--it gets the attention of the person or people being addressed by naming them—“Can you tell me, children

[DirA]

, that you will be good?”

Level 3 - Adding Clauses (Subordinate and Main)

L e e v e e l l l 3 .

.

.

1 T h e e B a s s s i i i c c s s s o f f f C l l l a u s s s e e s s s

Level 3.1.1 Compound Main Clauses (Punctuation and Logic)

A clause is a subject / finite verb / complement pattern and all the words that go with it. By this point in their work, students should be very comfortable with identify

S/V/C patterns, so “clause” is a relatively easy concept. For students, KISS distinguishes

“clause” from “sentence” by exercises on compound main clauses. Students are told to put a vertical line after each main clause:

He

did it

(DO) very well

| and people

laughed

{at him} .

|

The sentence is from Hans Andersen’s “The Snow Queen.” Note that there is no comma before the “and.” In KISS, students study punctuation by examining sentences from real texts.

In addition to identification, this section includes numerous exercises on the use

(and logic) of colons, semi-colons, and dashes to join main clauses. (Many of the commasplices and run-ons in students’ writing result from the students not knowing how to use these three punctuation marks. In other words, the students sense the logic, but not knowing how to indicate it in writing, they either use a comma or ram two main clauses together.

Colons and Dashes to Indicate Further Details

A colon or a dash can be used to indicate a “general/specific” relationship between the ideas in two main clauses:

The weather was nice—it was sunny with a soft wind.

The payment is late: it was due two weeks ago.

In these examples, the first main clause makes a general statement, and the second provides more specific details.

Semicolons to Emphasize Contrasting Ideas

Consider the following two sentences:

He went swimming. She did the dishes.

In effect, they simply state two facts. We can combine them with “, and” and a small “s,” but they will still simply state two facts:

He went swimming, and she did the dishes.

There is, however, another way of combining the two, and it changes the meaning. When a semicolon is used between two main clauses, it suggests that the clauses might embody contrasting ideas. Thus, we could write:

He went swimming; she did the dishes.

The semicolon invites the reader to think about the differences between the two main clauses, and, in this case, a little thought suggests that the underlying contrast here is that he is having fun, but she was stuck working in the kitchen.

Semicolons to Indicate Cohesion

Another little studied function of semicolons is to hold main clauses together, thereby separating them from the clauses that precede and follow them. Examples of this take up a lot of space because the sentences themselves are long, and one needs to include what comes before and after. I myself have noticed this just recently, but if you are interested, you can study the semicolons you see for yourself.

Level 3.1.2 Subordinate Clauses

Subordinate clauses are identified by red brackets. The function of the clause follows the opening bracket. Subordinate conjunctions that have no other function are in bold red. The following are from Alice in Wonderland by Lewis Carroll:

Dinah [DirA] , my dear, I

wish

[DO you

were

down here {with me} ] ! |

“Dear” can be explained as another Direct Address or as an appositive to

“Dinah.” (See below.)

Her first idea

was

[PN that she

had

somehow

fallen

{into the sea} ] . |

The question

is

, [PN

what

(DO of “find”)

did

the archbishop

find

?

] |

“What” is simultaneously the subordinating conjunction and the direct object of “find.”

She

had put on one

(DO) {of the Rabbit’s little white kid-gloves} [Adv.

(time) to

“had put on” while she

was talking

] . |

When students first begin to learn about subordinate clauses, they are not expected to identify their logical function (time, space, cause/effect, etc.), but I sometimes add that information FYI.

Quotations as Direct Objects

Quotations as direct objects raise a question that I have never seen discussed in a grammar textbook. Consider the following sentence(s):

The people of the village cried, “O brothers, your words are good. We will move our lodges to the foot of the magic mountain. We can light our wigwam fires from its flames, and we shall not fear that we shall perish in the long, cold nights of winter.”

If we ask the question “cried what?”, in one sense the entire quotation is the answer. But the quotation itself includes several sentences. (In some cases, they contain several paragraphs.) Since a period ends a sentence, does this sentence end after “good,” or does it continue all the way to “winter”? To decide where to put brackets and vertical lines, we need a consistent answer to this question.

The KISS Grammar view is that the first main clause ends at the end of the first main clause within the quotation. In this case, that would be “good.” Thus, in KISS, this passage would be analyzed like this:

The people {of the village}

cried

, [DO “O [Inj] brothers [DirA] , your words

are good

(PA) ] . | We

will move

our

lodges

(DO) {to the foot} {of the magic mountain}.

| We

can light

our wigwam

fires

(DO)

{from its flames} , | and we

shall

not

fear

[DO that we

shall perish

{in the long, cold nights} {of winter} ]

.” |

Restrictive and Non-Restrictive Constructions

One of the sections on subordinate clauses addresses the use of commas in restrictive and non-restrictive clauses. The basic, textbook either/or distinction between

“restrictive” and “non-restrictive” is very simple—and too simplistic: A “restrictive” clause restricts (limits) the meaning of the word that it modifies. The first thing we should

note here is that most textbooks make this distinction only with subordinate clauses, but if you analyze randomly selected texts, you will probably conclude that it also applies to prepositional phrases and other constructions. The basic rule of punctuation is that restrictive clauses should not be set off by commas, but non-restrictive clause (which do not identify or “restrict” the meaning of whatever is being modified) should be so set off.

The man who robbed the bank is still in prison.

She played for the team that won the title.

In both of these examples, we could say that the subordinate clause identifies the word it modifies and is thus essential to the meaning of the sentence. But that judgment is out of context. Suppose it was part of the following:

Yesterday, the police arrested a man and a woman for bank robbery. The man, who robbed the bank, is still in prison. The woman, who drove the getaway car, is out on bail.

The KISS approach to this is to give students a modified version of the normal textbook instructions, and then to give them sets of sentences that contain some obvious cases for restriction or non-restriction, plus some ambiguous cases. Having done the exercises, students should discuss their responses in class.

Level 3.1.3 Embedded Clauses and the Analytical Process

The embedding of subordinate clauses is an important concept, but it really does not introduce any new concepts. The following example is from Dickens’ A Tale of Two

Cities :

They

looked

{at one another} , [Adv.

(time) to “looked” as he

used

his blue

cap

(DO) to wipe his face, [Adj.

to “face” {on which} the perspiration

had started

afresh [Adv.

(time) to “had started” while he

recalled

the

spectacle

(DO) ]]] . |

A note explains that “face” is the direct object of the verbal (infinitive) “to wipe.”

The infinitive phrase functions as an adverb of purpose to “used.”

Currently, grammar textbooks do not even discuss the embedding of clauses.

L e e v e e l l l 3 .

.

.

2 A d v a n c c e e d Q u e e s s s t t t i i i o n s s s a b o u t t t C l l l a u s s s e e s s s

Level 3.2.1 –Ellipsis in Clauses

This section starts with a stylistic figure called prozeugma—the omission of a word because it appears in the preceding clause. From Marshall’s

Stories of Robin Hood :

At dinner the Sheriff

sat

at one end of the table and the old butcher *

sat

* at the other.

Other exercises introduce a variety of examples of ellipsis in clauses, but the only one that needs explanation here is the “Semi-reduced clause.” In Jules Verne’s

Twenty

Thousand Leagues Under the Seas , the following sentence appears:

One saw, while crossing, that the sea displays the most wonderful sights.

“While crossing” is considered a semi-reduced clause. It is a reduction of “while *one was* crossing,” but it can be further reduced to a gerundive—“Crossing, one saw.”

Level 3.2.2 “So” and “For” as Conjunctions

Whereas most (but not all) grammar textbooks define “so” and “for” as coordinating conjunctions, in KISS they can be either, depending on the punctuation.

Preceded by a colon or semicolon, they are considered coordinating; preceded by a comma, they are subordinating. The following sentence is from Andrew Lang’s

“Thumbelina”:

Neither the mole nor the field-mouse

learnt anything

(DO) {of this} ,

[Adv.

(cause) to “learnt” for they

could

not

bear

the poor

swallow

(DO) ] .

|

A semicolon before “for” would make it two main clauses:

Neither the mole nor the field-mouse

learnt anything

(DO)

{of this} , | for they

could

not

bear

the poor

swallow

(DO) .

|

My initial reason for making this distinction is that “so” and “for” introduce various cause/effect clauses, whereas “and,” “or,” and “but” distinguish parts from wholes.

The more examples I collected, the more interesting “for” became as a conjunction. That question is too complex to be discussed here, but I’ll note that in

The

Four Loves C. S. Lewis explains that a misunderstanding of “for” has resulted in thousands of people misinterpreting “Her sins, which are many, are forgiven her, for she loved much.” (Luke VII, 47) (155-6)

With one possible exception, within KISS these two conjunctions can be always considered coordinating. The exception is statistical studies of words per main clause and subordinate clauses per main clause.

Level 3.2.3 Interjection? Or Direct Object?

Can we always distinguish main from subordinate clauses. This section begins with an exercise that explores that question. In Andersen’s “Snow Queen” we find the sentence:

You see that all our men folks are away, but mother is still here, and she will stay.

Are the last two clauses direct objects of “see,” or are they separate main clauses. Unless there is something in the context that answers that question, they can be either:

You

see

[DO that all our men folks

are

away ] , but [DO mother

is

still here ] , and [DO she

will stay

] . |

You

see

[DO that all our men folks

are

away ] , | but mother

is

still here , | and she

will stay

. |

In statistical projects, KISS uses the second alternative.

The second set of exercises in this section explores subordinate clauses as interjections. The following is from Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Seas by Jules

Verne.

This faculty [Inj – I

verified it

(DO) later

—

] gave him a range of vision far superior to Ned Land’s.

In view of the preceding, KISS considers the “speaker” pattern an interjection in sentences such as

“Here you see me, madam,”

[

[Inj]

said

he , ] “keeping my word.”

In some cases, these interjections are not in quotations:

No one, [

[Inj] I

can assure you

(IO) , ] ever ventured on to his estate.

Rhetoricians, by the way, call these “interjections” parenthetical constructions because they are often set off by parentheses.

Level 3.2.4 “Tag” and Other Questions about Clauses

This is the collection point for other, relatively rare questions about subordinate clauses. In sentences such as “He had other ideas, did he?” linguists call “did he?” a “tag question. KISS considers it an interjection. In essence, these tag questions are comparable to tag statements, as in “But it does explain things, you know.” KISS also explains these as interjections. (Both examples are from Agatha Christie’s Postern of Fate ).

This section also focuses on “which” and “whom.” There is a witch in “which”— the word has some magical powers. Most pronouns refer to nouns or pronouns that are called their “antecedents.” (“Antecedent” means something that came before them.)

“Which,” however, has the magical power of referring to an entire clause, verb, or other construction. In the following sentence, for example, the antecedent of “which” is the entire clause, “George’s health was improving.”

George’s health was improving, which made his wife happy.

We can see this by restating the idea without the “which”: “That George’s health was improving made his wife happy.”

Another special power of “which” and “whom” is that they can function as a subordinating conjunctions without being the first word in the subordinate clause:

He

loved beefsteak

(DO) and fried

potatoes

(DO) , [Adj.

to “potatoes” the latter {of which}

was

his absolute favorite

food

(PN) ] . |

{At the party} , they

met

several

people

(DO) , [Adj.

to “people” one {of whom}

was

an

artist

(PN) ] . |

KISS Level Four - Verbals (Gerunds, Gerundives, and Infinitives)

In Level 2.1.6, students learn how to distinguish finite verbs from verbals, but they do not need to know the types of verbals. In the analysis keys to the exercises, verbals are usually identified in the notes, so you might want to study the following.

Identifying the Three Types of Verbals

Many current textbooks do not even mention “verbal,” but the concept is important. Sometimes, more is less, and this is such a case. As noted in the discussion of

Level 2.1.6, verbals, like finite verbs, can have complements. They are also modified by

adverbs and have subjects. There are three, and only three, types of verbals, and they should be introduced in the following sequence:

Gerunds always function as nouns.

Subject : Swimming is good exercise.

Object of Preposition: Mary was thinking (about playing golf.)

Predicate Noun: The best hobby is reading .

Direct Object: They love skiing .

Gerundives “always” function as adjectives.

Having rested

, the students went to the dance. [“Having rested” modifies

“students.”]

The book was on the table, closed and covered with dust. [“Closed” and

“covered” modify “book.”

Infinitives function as nouns, adjectives, or adverbs.

Most textbooks refer to gerundives as “participles,” but to do so is confusing. “Participle” designates the form of the word—the “-ing,” “-ed,” “-en,” etc. ending. Both gerunds and gerundives have participial form. Infinitives do not.

Noun : To eat is what I want to do .

Adjective: This is a good place to rest . [“To rest” modifies “place.”]

Adverb: They came to play

. [“To play” tells why they came.]

The easiest way to identify infinitives is by the principle of exclusion: if a verb is not finite, not a gerund, and not a gerundive, then it has to be an infinitive. There is no other choice left. (The “to” with many infinitives helps, but not all infinitives include the “to.”)

The Subjects of Verbals

The second exercise on mixed verbals focuses on their subjects. The subject of a gerund is expressed as a possessive noun

: “The crickets’ chirping kept me awake.” If the gerund denotes a general action, performable by anyone, the subject is usually ellipsed: “*Anyone’s* swimming is good exercise.” This expanded sentence sounds strange, and indeed it is: we have become accustomed to ellipsis. But when the subject of

a gerund is ellipsed, it is always there, understood. Note, for example, that no one would interpret “worms” as the subject of the sentence, but who would not accept deer or dogs?

Since a gerundive is a verb that functions as an adjective, the subject of a gerundive is the noun or pronoun it modifies . It is that simple. Note, by the way, that many “misplaced” or “dangling” modifiers are gerundives that are too close to the wrong word. As a result, the reader chunks them to the wrong thing.

The subject of an infinitive, if expressed, is in the objective case . This question of case is meaningful only in relation to pronouns (“Let us go”), because nouns in

English no longer show a distinction in case. Frequently, the subject of an infinitive is simply understood: in “Bill wanted to see the museum” it is clear that Bill wanted Bill to see the museum, otherwise the subject of the infinitive would have been supplied: “Bill wanted Mary to see the museum.”

Gerunds as Nouns Used as Adverbs

If they are taught in the KISS sequence, gerunds are relatively easy to master.

They also simplify the explanation of some words. Years ago, someone asked (on a grammar discussion list) for an explanation of, if I remember correctly, “hunting” in

“They went hunting.” I collected the responses—fifteen pages of different explanations using a wide variety of grammatical terms. In KISS, the answer is easy. “Hunting” is a gerund. Thus it functions as a noun. Nouns can function as adverbs. (Remember Level

2.3?) Thus “hunting” is a gerund that functions as a Noun Used as an Adverb.

The Complexities of Infinitives

Infinitives are the most complicated of the verbals. Many of their functions are simple, but they also enable KISS to eliminate what many textbooks confusingly call

“subjective” and “objective” complements. Perhaps the writers of textbooks did not see this because these infinitives are ellipsed. The following examples are from The Secret

Garden , by Frances Hodgson Burnett.

Once she crept into the dining-room and found it empty.

Once she

crept

{into the dining-room} and

found

it *to be* empty. |

“If” is the subject and “empty” is a predicate adjective to the ellipsed infinitive “to be.” The infinitive phrase functions as the direct object of

“found.”

She thought Mrs. Medlock the most disagreeable person she had ever seen.

She

thought

Mrs. Medlock *to be* the most disagreeable person [Adj.

to

“person” she

had

ever

seen

] .

“Mrs. MedlockI is the subject and “person” is a predicate noun to the ellipsed infinitive “to be.” The infinitive phrase functions as the direct object of “thought.”

KISS Level Five – The Additional Constructions

Three Level Five constructions were presented earlier in Level 2.3.

Level 5.4 Appositives

[App]

Most definitions of “appositive” limit the concept to nouns, i.e., two nouns joined by their referring to the same thing with no preposition or conjunction joining them:

They are in Winchester, a city in Virginia.

Mary, a biologist, studies plants.

Whole/Part Appositives

Many textbooks also point out that the relationship between an appositive and the word to which it is in apposition does not have to be one of strict equality. Often the appositives refer to parts:

The car has several new features—an electric motor , side airbags , and an alloy-aluminum frame .

As the following sentence from Theodore Dreiser’s “The Lost Phoebe” illustrates, the

“equality” aspect of an appositive can be stretched:

Beyond these and the changes of weather— the snows , the rains , and the fair days

—there are no immediate, significant things.

“Snows.” “rains” and “fair days” are not “changes”; they are what the weather changes to and from.

The “part/whole” relationship of appositives suggests another way of looking at the fairly frequent use of “all” after a noun. In this case, the “all” emphasizes the

“whole”:

They all went to the movies.

Although we could consider “all” here to be an adjective that appears after the noun it modifies, some people may prefer to see it as a pronoun that functions as an appositive to the preceding pronouns or nouns.

Reflexive Pronouns as Appositives

Reflexive pronouns (“myself,” “yourself,” etc.) function as appositives:

He himself would never have done that.

Repetitive Appositives

As sentences become longer and more complex, a word is sometimes repeated and functions as an appositive:

The cat had eyes that glowed in the dark light of the quarter-moon night, eyes that held him entranced until he heard a scream in the distance.

Elaborated Appositives

The problem with almost all grammar textbooks is that they teach the definitions of simple constructions but never explore them in context. This section, for example, includes exercises on elaborated appositives. The following sentence is from Theodore

Dreiser’s beautiful story “The Lost Phoebe”:

Near a little town called Watersville, in Green County, perhaps four miles from that minor center of human activity, there was a place or precipice locally known as the Red Cliff, a sheer wall of red sandstone, perhaps a hundred feet high, which raised its sharp face for half a mile or more above the fruitful cornfields and orchards that lay beneath, and which was surmounted by a thick grove of trees.

This is the analysis key:

{Near a little town} called Watersville [#1] , {in Green County} , perhaps four miles [NuA]

{from that minor center} {of human activity} , there

was

a

place

(PN) or

precipice

(PN) locally known [#2]

{as the Red Cliff} , a sheer wall [#3]

{of red sandstone} , perhaps a hundred feet [NuA] high [PPA] , [ Adj. to “wall” which

raised

its sharp

face

(DO)

{for half a mile or more} {above the fruitful corn-fields and

orchards} [Adj.

to “corn-fields” and “orchards” that

lay

beneath ]] , and [Adj. to

“wall” which

was surmounted

(P)

{by a thick grove} {of trees} ] . |

Notes

1. “Watersville” is a retained predicate noun after the passive gerundive “called.”

“Called” modifies “town.”

2. “Known” is a gerundive to “place” and “precipice.”

3. “Wall” is an appositive to “Red Cliff,” and ultimately to “place” and “precipice.”

I have included all of the above both to give an example of the kind of analysis that students will be capable of when they get to the higher levels of KISS, and to illustrate how a simple appositive in this case connects everything that comes after it to the main S/V/C pattern.

Other Constructions as Appositives

Some fuddy-duddy grammarians will have fits about these, but if you think about it, you’ll probably agree with me that other constructions can function as appositives, even if they are joined by conjunctions. Here I can give only a few samples. If you’re interested, you can find more in Level 5.4 in the “Master Collection” on the KISS site. I first noticed it in the sentence:

She struggled, kicked and bit, until her attacker let her go.

The three finite verbs do not denote three distinct acts: “struggled” denotes a general concept which is made more specific in “kicked” and “bit.” Can we not then say that the last two finite verbs function in apposition?

Gerunds can function as appositives:

I brought off a new trick, jumping off Herakles with a standing back-somersault, and landing on my feet.

The “trick” is the “jumping off Herakles” and “landing on my feet.” The gerunds do not just describe the trick—they are the trick.

So can subordinate clauses:

Jack told the King his story, how he had lost the great castle, and how he had twelve months and a day to find it.

The two subordinate clauses function as appositives to “story.” The two clauses do not describe the story—they are not adjectival clauses; they are the story. Delete “his story” from the sentence, and the two clauses become the direct objects of “told.” Normally, you cannot delete the nouns that adjectives modify and still have the sentence mean essentially the same thing.

Mixed Construction Appositives

In the following sentence, written by a college student, the apposition is between an infinitive phrase and a noun:

Left alone, and needled by that nagging sense of guilt, she busies herself cleaning house and lets the “coffee pot boil over ,” an effective image to describe her anger, which is short lived, as night softens her memory of the harsh morning light and she falls prey to her lust again.

I can’t think of a better way to explain the function of “image” than as an appositive to the infinitive phrase.

I have spent some time on appositives because they embody the basic same/different relationship that is the basis of all logical thinking. Shouldn’t we help students see that logic?

Level 5.5 Post-Positioned Adjectives

[PPA]

Most adjectives appear before the nouns that they modify, but some appear after them. (The Latin term for this is “post.”) In the following sentence, for example, “happy” and “hopeful” are adjectives that describe “Marilyn.”

Marilyn arrived early, happy with her success

and hopeful for the future.

Frequently these adjective appear quite close to the noun or pronoun that they modify, but they can be separated from them by other constructions, as in the following sentence from Ouida’s

The Dog of Flanders :

There was only Patrasche out in the cruel cold

—old

and famished and full of pain.

Most students could probably figure this out for themselves, but KISS includes it as a separate construction so that it can be explored in statistical studies. It appears to be a

“late-blooming” construction, for many people, perhaps after high school.

Level 5.6 Delayed Subjects and Sentences

[DS]

“Delayed Subjects and Sentences” simply denote sentences that have a placebo subject (almost always “it”) with the meaningful subject delayed until later in the sentence. For example,

That he was late is true.

Sometimes it may make more sense to consider the sentence, rather than the subject to be delayed, as in

It is true that he was late. means

It was Bob who was playing baseball in his back yard, means

Bob was playing baseball in his back yard.

In cases like this, delaying the sentence puts more emphasis on the question of who was playing. Ultimately, however, the delayed subject slides into the delayed sentence such that either explanation can be considered acceptable.

Level 5.7 Passive Voice and Retained Complements

(P)

,

(RDO)

,

(RPN)

,

(RPA)

The active / passive voice distinction is not central to sentence structure—it is not primarily a question of nexus or modification. This means that students do not need the distinction in order to explain how every word in any sentence chunks to the main S/V/C pattern. Why then should they learn it? There are two answers to that question. First, it is important to good reading. Passive voice eliminates the “doer” of the action expressed in the verb and thereby side-steps the question of responsibility:

Taxes were raised.

A bomb was dropped.

Workers were laid off.

People who recognize passive voice are much more likely to ask “Who raised the taxes?”

“Who dropped the bomb?” “Who laid off the workers?” And, in turn, the “Who?”

question leads to “Why?” Some teachers believe that the ability to recognize passive voice makes students more responsible readers—and more effective citizens.

Unfortunately, other teachers forbid the use of passive voice. This is somewhat silly in that these teachers forbid the use of passive voice in a context in which most students can’t recognize passive voice in the first place. The result is that the teachers object to passive voice, when they recognize it in the students’ writing, but students, not understanding, simply do what the teacher says and shrug off the question. Thus, the second reason for teaching passive voice, especially in a KISS context, is to enable students to understand—and even object to—what these extremist teachers are demanding.

Identifying Passive Voice

The first exercises in this section help students to identify passive voice. The instructional material is a bit long, so here I’ll simply give a few examples. In essence, passive voice makes the direct object is an active voice sentence into the subject, and the subject (the doer), if given, is put in a prepositional phrase. In the keys, passive voice is noted by

(P)

.

Active: The police suspect him of being an accomplice.

Passive: He is suspected

(P)

by the police of being an accomplice.

Active: No one invited them.

Passive: They weren't invited

(P)

.

Active: Someone will ask you to dance.

Passive: You will be asked

(P)

to dance by someone.

Active: Has he repaired the starboard pump?

Passive: Has the starboard pump been repaired

(P)

?

Passive Voice or Predicate Adjective?

A second set of exercises explores the difference between passive voice and gerundives that function as predicate adjectives. Consider:

1. He

was worried

(PA) about the game.

2. The Eagles

were defeated

(P)

by the Giants.

In (1), “worried” describes the emotional state of “He” more than it denotes any particular action. But in (2), “were defeated” denotes a specific action performed by the

Giants. Thus some grammarians would consider “worried” a predicate adjective, whereas

“were defeated” should be considered as passive voice. In effect, the two constructions,

S/V/PA and passive voice, slide into each other, and thus how you should explain it may depend on how you interpret the sentence.

Retained Complements after Passive Verbs

Transformational grammarians consider the active voice primary and passives as transformations of active voice sentences. Thus predicate nouns, predicate adjectives, or direct or indirect objects that appear after passive verbs are considered “retained” from the active. In

Bill

was given

a

dollar

(RDO) .

“was given” is passive, so the complement, “dollar” is a retained direct object. Similarly, you will find retained predicate adjectives and retained predicate nouns:

Murray

was considered

(P)

foolish

(RPA) .

Terri

was made

(P)

a

queen

(RPN) for a day.

If we ask, “Murray was considered what?”, the answer is “foolish.” Since “was considered is passive, and since “foolish” is an adjective that describes Murray, “foolish” is a retained predicate adjective. Similarly, if we ask, “Terri was made what?”, the basic answer is “queen.” Since “was made” is passive, and since the sentence means that Terri equaled a queen for a day, “queen” is a retained predicate noun.

Theoretically, any construction might function as a retained complement, but infinitives are relatively common:

Herman

was asked

(P)

to help

(RDO) .

The active voice version of this would be “They asked Herman to help.” In that version,

“Herman” is the subject of the infinitive “to help,” and the infinitive phrase is the direct object of “asked.” Thus in the passive version, the infinitive functions as a retained direct object after the passive verb.

Subordinate clauses are also fairly frequent, especially if the indirect object of the active voice version becomes the subject of the passive:

Active: They

told Terri

(IO) [DO that Tom

likes her

(DO) ] .

Passive: Terri

was told

(P) [RDO that Tom

likes her

(DO) ] .

If the subject of the passive verb is “it,” some cases can be explained either as a retained complement or as a delayed sentence:

It was already said that Tom likes Terri.

Because “was said” is passive, we can explain this as a retained complement from the active voice:

Someone already

said

[DO that Tom

likes Terri

(DO) ] .

But we can also consider it a delayed sentence version of:

[Subj. That Tom

likes Terri

(DO) ]

was

already

said

(P) .

“To be to”—Ellipsed Passive plus an Infinitive?

Something is missing (ellipsed) in the following sentence from Heidi by Johanna

Spyri:

The telegram was to be mailed that night.

It could mean two slightly different things:

Active Voice: The telegram

was *going* to be mailed

that night

[NuA]

.

|

Passive Voice: The telegram

was *supposed*

(P)

to be mailed

(RDO) that night

[NuA]

.

|

Out of context, either explanation makes sense. But there is a difference. Consider an example from Black Beauty , by Anna Sewell:

James was to drive them.

Active Voice: James

was *going* to drive them

(DO) .

|

Passive Voice: James

was *expected*

(P)

to drive

(RDO) them

(DO of “to drive).

|

The active voice version states a simple fact and almost suggests that James wants to drive them. The passive version, on the other hand, suggests that some else expects James to drive them.

To determine which alternative is better, consider the context of the sentence. In the example from Heidi , the passive explanation is better because the context indicates that the Grandfather told Peter to mail the telegram that night.

Level 5.8 Noun Absolutes

[NAbs] Error! Bookmark not defined.

Noun Absolutes are the last construction that students need to learn. They are rarely discussed in grammar textbooks, simply because one needs to be able to identify clauses and verbals before absolutes make much sense. A noun absolute consists of a noun plus a gerundive. The adverbial function of absolutes, as in the following sentence from Black Beauty, is universally accepted by grammarians.

So we

went

on, John chuckling all the way home.

Frequently, the gerundive “being” is ellipsed, as in the following from Theodore

Dreiser’s “The Lost Phoebe”:

He

fell

asleep after a time, his head *being* on his knees.

Noun Absolutes as Nouns

That noun absolutes also function as nouns is generally ignored or denied by many grammarians, probably because they don’t read enough or think. One of the reasons for their failures is that academics, generally, are too much influenced by scientific fields in which “new information is crucial.” Thus, even though George O.

Curme is acknowledged as one of the two greatest early twentieth century grammarians, graduate students in English or Linguistics rarely study his work of.

In Volume II of his A Grammar of the English Language (Essex, Conn. Verbatin,

1931, 1986), Curme discusses the “Nominative Absolute in Subject Clauses,” and gives, among his examples,

She and her sister both being sick makes hard work for the rest of the family. (157)

Despite the differences in grammatical terminology, “She and her sister both being sick” is a noun absolute and it functions as the subject of “makes.”

Curme also gives an example of what we can call a noun absolute used as a predicate noun:

Cities are man justifying himself to God . (158)

The key question here is meaning. In other words, if we tried to consider “man” as a predicate noun, the explanation would suggest that “Cities” = “man” modified by the gerundive “justifying.” But the “justifying” is just as important as is “man.” And the equal importance of “man” and “justifying” is better explained grammatically by considering “man justifying himself” as a noun absolute construction.

Curme also gives examples of what we can consider noun absolutes that function as 1.) an object of a preposition, and 2.) an appositive:

1.) She is lonesome { with her husband so much away }. (155)

2.) Well, that is just our way, exactly— one half of the administration always busy getting the family into trouble, the other half busy getting it out again .

(158) [From Mark Twain]

He does not give examples of the noun absolute functioning as a direct object, but if we accept his logic and other examples, it is easy to see many such cases. A simple example is the following sentence from Black Beauty:

I don’t like to see them held up.

To say that “them” is the direct object of “don’t like” is surely contrary to the meaning of the sentence. What isn’t liked is “them being held up.” If we want a descriptive grammar that aligns the grammar with meaning, the noun absolute that functions as a noun is a very sensible construction.

L e e v e e l l l 6 A d v a n c c e e d a n d A d d i i i t t t i i i o n a l l l E x e r r c c i i i s s s e e s s s

Level Six is a collection point for exercises and projects that do not fit neatly in the original five levels.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

1 S t t t u d i i i e e s s s i i i n P u n c c t t t u a t t t i i i o n

This section includes a wide variety of punctuation marks, particularly KISS

“General” punctuation exercises in which the capitalization and punctuation has been stripped from a text and students are asked to “fix” it. There are also some suggestions for research projects.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

2 S t t t y l l l e e — F o c c u s s s , , , L o g i i i c c , , , a n d T e e x t t t u r r e e

Here you will find exercises on parallel constructions, focus, logic, and texture, and exercises in which students are asked to compare two versions of the same text.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

3 S t t t y l l l e e

—

S e e n t t t e e n c c e e C o m b i i i n i i i n g a n d D e e C o m b i i i n i i i n g

KISS proposes two different types of combining and de-combining exercises—

“Directed” and “Free.” In “Directed” exercises, students are expected to use specific constructions. For example, “Combine the sentences by making one a subordinate clause in the other.” In “Free” exercises, they are given a short text that has been de-combined into very short sentences. They are asked to combine the sentences so that they “sound better.” Ideally, the students will share and discuss their versions with the class.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

4 R e e s s s e e a r r c c h P r r o j j j e e c c t t t s s s o n G r r a m m a r r

These projects range from surveying the public’s knowledge and use of grammar to studies of various words. Many of them can be done most easily by using a computer:

Select an electronic text and by using the “Find” function search for “But.” Copy the examples that you find of “But” used to begin a sentence.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

5 S t t t a t t t i i i s s s t t t i i i c c a l l l S t t t y l l l i i i s s s t t t i i i c c s s s a n d A d v a n c c e e d A n a l l l y t t t i i i c c a l l l Q u e e s s s t t t i i i o n s s s

This is the home for KISS statistical studies. You may have noted, in the “Ideal

Grade” sequence, that starting in third grade, two statistical studies are proposed for each year. Starting in fourth grade, these statistical studies are very close to the important professional studies that were done in the 70’s and 80’s. By ninth grade, the students will be able to do better studies than the professionals did.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

6 S y n t t t a x a n d W r r i i i t t t i i i n g

For now, this is the primary home for KISS writing assignments. As the “Ideal”

Sequence is developed, this area should bloom.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

7 S y n t t t a x i i i n R e e s s s e e a r r c c h P a p e e r r s s s

Some of my readers will be shocked to learn that both of the following sentences came from students’ papers that ended up with an “A” in my college Freshman

Composition course:

In an article by David Glenn, a senior reporter for The Chronicle of

Higher Education

, expresses Dweck’s idea of a growth mindset as thinking about intelligence as “malleable, rather than as properties fixed at birth” (1).

According to Michael Graham Richard, a journalist for Discovery, says that those with a growth mindset see failure as an opportunity to improve, they learn from challenges, they see “effort as the path to mastery”, and instead of fearing criticism they take it eagerly and learn from it (4).

In the first, there is no subject for “expresses,” and in the second, no subject for “says.”

In my (and their) defense, I use a very detailed rubric for grading, there is a lot to be graded in such papers, and I deduct one point for each sentence error. That does not mean that I am happy about those A’s, but students have received very poor, if any, instruction in grammar (and writing), and they can’t master everything in one college semester. Students who learn KISS grammar will probably not have such problems, but in the “Ideal” KISS sequence, instruction in writing research papers is tentatively scheduled for grade ten.

This section is the beginning of a collection of exercises that will deal directly with using voice and credibility markers.

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

8 M i i i x e e d R e e v i i i e e w a n d A d d i i i t t t i i i o n a l l l P a s s s s s s a g e e s s s f f f o r r A n a l l l y s s s i i i s s s

Review and passages for analysis appear throughout the five KISS levels, but they are usually aimed for the specific construction under study. This section include more general exercises, including prose, poems, plays, and jokes (“Just for Fun”).

L e e v e e l l l 6 .

.

.

9 A s s s s s s e e s s s s s s m e e n t t t Q u i i i z z z z e e s s s

As its name suggests, this is the collection point for assessment quizzes. Right now it is heavy on first and second grade, but there are some examples of quizzes for higher grades.

I I I n d e x o f f f C o d e e s s s

(DO) ............ 5, 8, 11, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 22, 27, 28

(IO) ................................................................. 5, 17, 27

(P) 3, 22, 25, 26, 27, 28

(PA) ...................................................... 5, 7, 10, 13, 26

(PN) ............................................ 6, 7, 8, 10, 17, 18, 22

(RDO) ................................................. 3, 25, 26, 27, 28

(RPA) .............................................................. 3, 25, 26

(RPN) .............................................................. 3, 25, 26

I don’t understand why (P) doesn’t right align, but these may be helpful.

[App] .................................................................... 3, 20

[DirA] ........................................................2, 11, 12, 13

[DS] ...................................................................... 3, 24

[Exp] ...................................................................... 2, 6

[Inj] ...........................................................2, 10, 13, 17

[NAbs] .................................................................. 3, 28

[NuA] ........................................................2, 10, 22, 28

[PPA].............................................................. 3, 22, 24