Session 9.3a

advertisement

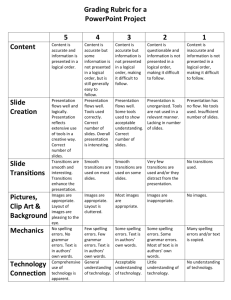

Session 9 Michael Bratton and Nicolas van de Walle, Democratic Experiments in Africa, 1997, pp. 1-18, 61-127 and 268-279 pp. 1-18, 61-96 INTRODUCTION The book begins with a brief narrative describing the the transition to democracy in Benin—“the first instance on mainland Africa when a national political leader was peacefully supplanted as a consequence of the expressed will of the people”—which the authors believe was emblematic of the democratic transitions that occurred throughout Africa during the first half of the 1990s. They argue that Benin’s transition embodied the three characteristics that distinguish transitions to democracy in Africa from those in other regions of the world: Sequential linkages/Causality The authors argue that most of the transitions in sub-Saharan Africa were precipitated by popular protest and followed a similar sequential/causal pattern: (1) protest (2) increased political liberties (3) increased incidence of elections (4) democratic consolidation. Time-series data shows that these trends peaked sequentially throughout the region, in 1991, 1992, 1993 and 1994, respectively. (On pp. 4-5, time-series trendlines illustrate this sequential-peaking trend graphically.) Bratton & van de Walle argue that the pervasiveness of this pattern suggests causality (an interesting endorsement of mass protest among citizens of nondemocratic regimes). Pace For the 35 sub-Saharan nations that sustained regime changes between 1990 and year-end 1994, the median interval between the advent of transition and the inauguration of a new government was just 35 months (pp. 4-5). While the authors marvel at how quickly these nations reformed, they also suggest that transition may have been accelerated at the expense of durable consolidation of democratic institutions and that instability may be a problem in the medium run. Nonlinearity On this point the authors explain that each of the phenomena in the sequence described above are episodic, and therefore are not represented graphically in a linear fashion. This is perhaps logical for elections and protests, which cannot occur continuously. It is less logical, however, in the case of political liberties and democratic consolidation. Nothing inheres in either of these phenomena that would preclude them from linearity, i.e., steady expansion. The authors point out that they have not been linear, however, and cite several specific cases of backlashes against democratization that have threatened the transition process in some countries. (Although the authors do not explicitly link the admonition they issued in their discussion of the pace of reforms, it seems fair to suspect that some of the backlash described here may be attributable to the speed of transition and the consequent fragility of democratic institutions.) Next Bratton & van de Walle consider the question of significance and ask whether the transitions that occurred during the first half of the 1990s marked a “watershed” in African politics. Their answer is a resounding but qualified “yes.” They argue that the reforms are significant insofar as they have introduced fundamental changes to the sub-Saharan political landscape in the areas of: (1) genuine political competition (2) change in leadership (3) regime. The table below summarizes their argument regarding each. characteristic competition Changes in African political landscape, 1990-1994 pre-1990 post-refo elections infrequent and largely ceremonial affairs in 1990-1994: 38 of 47 countries which result was a foregone conclusion held competitive elections; opposi from 1985-1989, only nine elections held in multiparty seats in 35 of those elections systems—the integrity of four was seriously compromised average share of legislative se change of leadership regime by systematic electoral fraud, restricted franchise or physical intimidation; in the remaining five, the space available to opposition parties was limited increased from 10 percent in 1989 29 “founding” elections > 90 percent of incoming national leaders appointed 11 democratic leadership trans prototypical regime: military oligarchies, one-party states, or hybrids of the two 1989: 29 sub-Saharan states governed under singleparty arrangement, 11 under direct military rule with “no pretense of political party institutions” by 1994, not a single one-part Africa; emergence of formalized, c pp. 6-8 To counterbalance this optimistic summary of democratic advances in Africa, the authors concede that there have been important continuities. They cite Herbst, who cautions against excessive optimism in noting:“in open presidential contest after 1990, just as many incumbents (15) were reelected as replaced (14).” Bratton & van de Walle also acknowledge that in many cases a change of leadership does not translate into changes in a country’s administration or policy, since leaders are drawn from the same socioeconomic and political pool from which previous leaders emerged. In many cases, the patronage, inefficiency and outright fraud remained rampant after changes of leadership. Finally, the authors define the terms and parameters they will use in analyzing democratic transitions. regime: set of political procedures that determine who can participate in politics and under what terms—may be formal or informal transition: shift from one regime to another—accurately characterized as a struggle over the rules and resources of the political game Following a brief detour into the realm of political philosophy, the authors provide a two-faceted definition of democracy. First, they define democracy procedurally, as a regime, and not substantively. Secondly, they evaluate regimes based on a minimal number of criteria rather than a comprehensive set of requirements. In the end the authors argue that the most basic requirement for democracy is that citizens are able to choose their leaders freely, fairly and in a binding way through rule-governed processes. “In our view, no other democratic institution precedes elections, either in timing or importance.” The authors indicate that analysis of democratic regimes thus defined must also encompass civil liberties, since they are essential in ensuring that choice is free and fair, but need not incorporate more restrictive criteria such as regime survival or consolidation. CHAPTER 2: NEOPATRIMONIAL RULE IN AFRICA Book asks whether regime transitions in SSA resemble democratization in other parts of the world. Answer: Africa differs in several significant respects, and these differences critcally affect the dynamics and outcomes of distinctive democratization processes. Chapter 2 reviews the nature of formal and informal political institutions in post-colonial Africa. Bratton/Van de Walle establish frameworks in which to look at distinctions among neopatrimonial regimes in SSA – based on the assumption that virtually all governance in SSA is neopatrimonial. Neopatrimonial Rule: Derived from concept of patrimonial authority, which Max Weber uses to designate principle of authority in the smallest and most traditional polities, where ordinary folk are treated as extensions of the “Big man’s” household. Weber distinguishes patrimonial authority from rational-legal authority, in which public sphere and private sphere carefully separated, and written laws and bureaucratic institutions In neopatrimonial rule, the right to rule is ascribed to a person rather than to an office. One individual, often president for life, dominates state apparatus and stands above the law. Officials occupy bureaucratic positions to acquire personal wealth ad status. Theorists suggest that neopartimonialism is a master concept for comparative politics in the developing world. Bratton and Van de Walle make distinction that neopatrimonial practices is the core feature of politics in Africa. Three informal political institutions typically stable, predictable and valued in Africa’s neopatrimonial regimes: Presidentialism: Systematic concentration of political power in the hands of one individual who resists delegating all but he most trivial decision-making tasks. Clientilism: Awarding of personal favors – typically form of public sector jobs – distribution of pulbic resources through licenses, contracts and projects. State Resources; Use of state resources for political legitimation – closely linked to the reliance on clientelism. As consequence of both clientelism and use of state resources, neopatrimonial regimes demonstrated very little developmental capacity. Distinguishing among neopatrimonial regimes according to extent of political competition (or contestation) and the degree of political participation (or inclusion): Political competition – varied extent in which some members of political system allowed to compete over elected positions or public policy. Political participation – varied in the degree of political participation allowed. Some sense of extent of political participation can be gleaned from voter turnout rates: which average from 85.2% to 39.3% in different countries. Five modal regimes: Bratton and Van de Walle layout five modal regimes, but argue that countries’ governance can transition between and among these modes. Plebiscitary One-Party system – Extremely limited competition but encouraged a high degree of political participation (ex: Ethiopia, Kenya) Military Oligarchies Exclusionary form of neopatrimonial rule – elections few or entirely suspended – all decisions made by narrow elite behind closed doors. (Liberia, Nigeria) Competitive One-Party Systems (Oxymoron?) Tolerates limited political competition at the mass as well as elite levels. Allow for two or more candidates in party primaries.(Cameroon, Zambia) Settler Oligarchies “Exclusionary democracy” – reproduced functioning democracies within their own microcosmic enclaves.(Namibia, SAfrica) Multiparty Systems Display relatively high levels of both participation and competition. (Botswana, Zimbabwe) TRANSITIONS FROM NEOPATRIMONIAL RULE – Looking at the extent to which the neopatrimonial nature of regimes affects process of democratization. Neopatrimonial practices cause chronic fiscal crises and inhibit economic growth. Tends toward particularistic networks of personal loyalty…recipe for social unrest. Mass popular protest likely to break out, usually over issue of declining living standards, and to escalate into calls to remove incumbent leaders. Endemic fiscal crises undercut capacity for rulers to manage political change…eventually government can’t meet civil payroll, and ultimately can’t meet military payroll. Ultimately, power is so concentrated that the disposition of the regime is synonymous with the personal fate of the supreme ruler. His overthrow or flight becomes the primary objective of the opposition throughout the transition, typically the single unifying issue of the opposition. In Neopatrimonial regimes, transitions are struggles to establish legal rules. Batton/Van de Walle argue that the pervasiveness of clientelism means that the state has actively undermined capitalist forms of accumulation. Property rights are imperfectly respected and there are disincentives vs. private entrepreneurship and long-term productive investments. Thus, during transitions, middle-class elements align with the opposition. In conclusion: political transitions are characterized by considerable uncertainty and some serendipity – the outcome of political struggles depends on the way that power was exercised by the rulers of previous regimes.

![Understanding barriers to transition in the MLP [PPT 1.19MB]](http://s2.studylib.net/store/data/005544558_1-6334f4f216c9ca191524b6f6ed43b6e2-300x300.png)