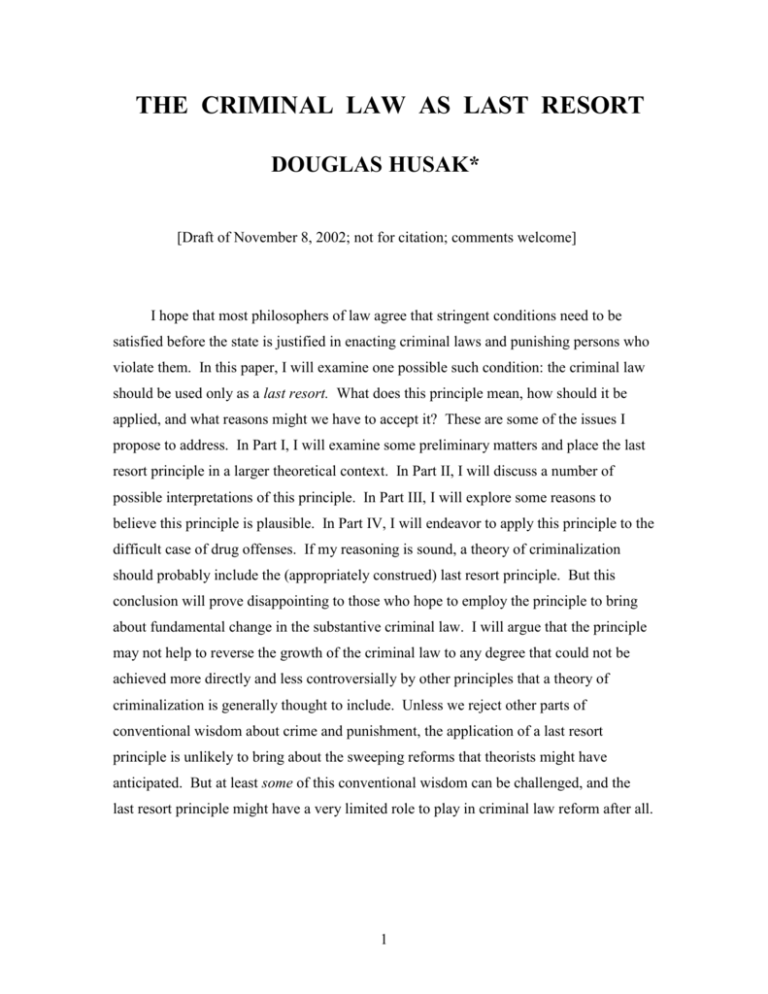

the criminal law as last resort - University of Pennsylvania Law School

advertisement