34. The Intellectual Revolution and Politics

The Intellectual Revolution and Politics

The Renaissance and the Reformation together undermined the dominance of the

Roman Catholic Church as well as that of Aristotle. These two developments unleashed questing minds in Western Civilization which analyzed natural phenomena along with ancient texts like the Bible. Convinced that the universe had been created by an orderly

Mind, individual thinkers used new tools for observation and other technological advances to launch the Scientific Revolution in search of that order, or of that Mind.

Western thinkers began to question everything. Protestant intellectuals wrestled, just as the Catholic Church did, with new discoveries made by Galileo’s telescope that seemed to contradict the Bible, but Protestants were not as a whole committed to Aristotle’s assertions. Before we look at the impact of this intellectual revolution on politics, a word about new interpretations of the Bible is in order.

Galileo’s telescope confirmed the Copernican heliocentric solar system, or at least seriously undermined the Catholic Church’s firm assertion that the Earth was where

Aristotle said it was, in the center. The Catholic Church interpreted the Bible’s assertion in at least three scriptures that the sun moved or miraculously stood still through the

“lens” of Aristotle’s model of the universe. When first challenged by the observations

Galileo recorded, the Church was adamant that these scriptures were literal and that his conclusions were thus heretical. Only later did the Church reconsider that, at least in the passage about Joshua’s asking God to stop the sun so he could have additional light and time to keep on killing his enemies, that “The sun stood still. . .” was not a literal statement of truth but merely a figure of speech in common use by people throughout time before the invention of the telescope (or God’s invention of Copernicus). They reasoned that God was not about to come down, stop the battle, and tell Joshua, “First, there’s something you have to know about the Earth and the sun.” Joshua, they said, was simply using language like that of even a modern weatherman, viz.

“The Sun rises,” or

“The Sun sets.” And then there’s the intriguing little scripture in the Book of Job

(thought by scholars to be the oldest book of the Bible) which says God made the Earth

“an orb that hangs on nothingness.” One wonders why Columbus had to convince

Christendom the world is round when its own scriptures called it an orb! Still, Job did not say, “The Earth rotates.”

In an intriguing case involving another new optical device, the microscope, intellectuals found themselves on various sides of the debate about human reproduction.

With the discovery of sperm in 1677 using a microscope, a theory about human reproduction long held seemed to be confirmed. Contrary to biblical teaching, science had thus “proven” that the father contributes a miniscule, yet complete, infant inside a sperm that is implanted in the mother’s womb. Some thinkers rushed to embrace this avant-garde scientific discovery. Other thinkers stood with the Bible in that it said Christ was born from the “seed of a woman.” The microscopic-baby theory lasted over 150 more years, however, until it was discovered in 1827 that women indeed do have “seed”

(the ovum). Not until 1843 was the actual process of fertilization understood (by scientists), and another intellectual/scientific/biblical question was “answered” (for now).

This process of inquiry and debate spawned the Intellectual Revolution. Theories have risen and fallen ever since. Some remain. Some are destined to fall. All are questioned, or should be.

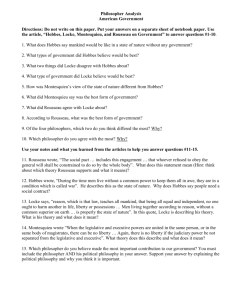

With questions, answers, and theories beginning to multiply, a key branch of inquiry became the analysis of society and government. While you will study further intellectual pursuits of a scientific nature in your science classes, here in the Social

Studies department we’ll focus on those associated with three men who can be considered the first “political scientists.” Two Englishmen: Thomas Hobbes (1588-

1679) and John Locke (1632-1704), and a Frenchman: Charles de Secondat, Baron la

Brede et de Montesquieu (1689-1755), together revolutionized how human beings thought and talked about their governments. Make no mistake about it, revolutionary talk about government eventually led to revolutionary actions, and Hobbes, Locke and

Montesquieu are villains or heroes depending on your perspective. With other intellectuals, they represent the crowning achievement of the Renaissance, the formation of a world where many people could make a living by thinking and writing!

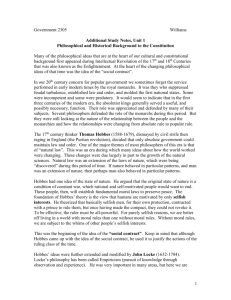

To begin, Thomas Hobbes theorized about many subjects. By the 1630s and independently of Descartes, he developed a mechanical conception of nature and theorized, like Newton, about light and color. Using mathematical reasoning he broached the subject of whether light behaved more like waves or like particles. He held a universal explanatory principle focused on motion and the interaction of moving bodies.

He can be said to be a father of psychology in that he claimed that sensation and imagery are results of an object moving something in the brain. He emphasized the importance of having theories tested and therefore contributed to the Scientific Revolution. Hobbes, however, is much more famous as a political theorist.

The son of a clergyman, he studied classical literature and became the tutor of an

English lord. Consequently, all his personal studies were patronized by virtue of this connection. In the context of his role as tutor, he said the purpose of studying history is the instruction of a governing social class in political prudence . These notions were readily available to him in Plato’s

Republic and the translation he personally completed of The History of the Peloponnesian War by Thucydides. Remember, Thucydides said the war was caused by the ambition of deranged leaders. Hobbes also studied Euclid’s geometry and then posited this marvelous definition of truth: Truth is clear definitions

and correct deductions of all their consequences . He found himself amidst a revolt against Charles I of England by Protestants, and as an observer of these events penned his chief work, Leviathan , published in 1651.

With this work, Hobbes viewed himself the father of political science. He said we can make exact definitions of everything involving the state because it was all man-made

(like geometry). When assessing any ideology, one should always begin by analyzing the view of human nature espoused by that doctrine. Hobbes had much to say about human nature, starting with the fact that mankind experiences incessant activity— we are never

done.

In terms of good and evil, Hobbes said what we desire is that which is good; what we fear is that which is evil. Man’s biggest desire is something we must agree to collectively achieve—self-preservation.

Hobbes addressed the question, “How does a community achieve Peace and

Order?” This quest is man’s greatest challenge because in a “State of Nature” life is

“solitary, poor, nasty, brutish, and short.” Men in this state are subject to no one. The

State of Nature produces constant war, and the combatants are ALL vs. ALL. There is

freedom, but no government (no justice and protection) and therefore endless insecurity.

Each man has a right to own—everything—including your stuff!

Hobbes is among the first thinkers to discuss the laws of Nature, a word which began to be capitalized. The foremost law of Nature for Hobbes was that men had

“natural rights,” especially the right to passionately pursue the desire to live by any means. Political order, then, was based on this right. Reason, another word that began to be capitalized, observed that to secure themselves, men had to give up the complete freedom of anarchy in order to achieve civilization (to seek peace). Here is why Hobbes was considered a radical. Do you see any part in that explanation for God or revelation of divine law? Hobbes said all that was beyond philosophy. Hobbes is among the first people to have an explanation for morality not based on a deity. He said values were derived by men of old striving for survival. Theft? Murder? Adultery? These acts were defined by men as evil because they undermined communities and therefore undermined peace and order and were therefore forbidden by natural law.

Now, some power had to determine that people consented to give up their freedom and lived by these agreed upon natural laws (and kept on doing so). Hobbes said unions of thinking men established contracts that even permitted coercion and punishment if the contract were broken. Hobbes coined the phrase, “Social Contract” to describe this concept. A common misconception is that people made a social contract with their king, but Hobbes actually said the Social Contract is among all the people themselves who then select their government (perhaps a king) to hold each other to the

Contract.

Regardless of the actual type of government (democracy/aristocracy/monarchy), the Social Contract gave sovereignty to the government making it the judge of what made for peace for all. Governments were also given the power to determine what should be taught, to make laws, to reward, to punish, to command the military, to make war, and to make peace. And wise men submit without believing they can revolt.

The word Hobbes chose for the sovereign was Leviathan , which some associate with Charles I. A sovereign Leviathan is above the law because the law is his will. But there was a loophole—do you see it? An individual did not have to obey a command from his sovereign to kill himself. Why not? Because the State created by the Social

Contract exists for self-preservation! A revolution under these circumstances was illadvised, at best. However, if one is going on, keep fighting. Why? Because the ultimate goal is self-preservation, and the king will now probably kill you himself.

The sovereign had duties toward his subjects, though. He was to provide for the safety and well-being of the people. The rule of his actions, then, was to beware. If he didn’t provide for the survival and happiness of his subjects, a rebellion was a natural consequence of natural law. The Leviathan ruled “by the consent of the governed.” No awe or reverence was due him because he ruled because he was permitted to rule. He ruled because he was useful. These ideas were a direct attack upon the concept of the divine right of kings.

Now, to John Locke. Locke was also patronized by a nobleman (whom he would have thus been unwise to offend). He was trained as a medical doctor but amidst the convulsion of the Restoration of a king (Charles II) to England and the subsequent

Glorious Revolution, Locke became interested in political and economic philosophy. He worked for one of the proprietors of the Carolina colony in America and was the author

of that colony’s constitution. In this document, The Fundamental Constitution of

Carolina, his fear of Catholicism and absolutism were expressed in a call for religious toleration. He had been raised hearing stories of the St. Bartholomew’s Day Massacre in

France back in 1572. During that episode, remember, Catholics had rampaged through the streets of Paris murdering over ten thousand French Protestants (called Huguenots) and around 100,000 nationwide.

Locke’s State of Nature was that each individual had freedom because he belonged to God and knew natural laws revealed by God. Men consent to live in a common society regulated by government divided into three branches: legislative, executive, and federative (diplomatic). If you were looking for judicial, there, Locke said it was in the hands of the people, not the government. Regarding property rights, Locke said each man possessed 1) his own life and 2) whatever he had taken that had neither harmed nor deprived anyone else. Self-preservation and property were the dual fundamental principles of his Social Contract. Therefore, he said government existed to preserve life, liberty, and property. If you were looking for the pursuit of happiness, you’ll have to wait for the Declaration of Independence.

Locke observed that families were the chief institution in society. The father and mother were guardians of children, not owners. Who owned the children? The children owned themselves (go back to each man’s possessions). The parents were obligated to educate children and then free them, with no arbitrary power over them. Locke found in this model the model for civilization. Locke’s Social Contract was an election of representatives who alone touch the property of other men through taxation, the cost of peace.

A key Lockean point is that the Social Contract could become out of balance, or arbitrary, like a father who abuses his children. Therefore, the best government is achieved by representation through majority rule (hence Parliament and Congress). A key distinction, however, is that Locke believed Reason confirmed natural laws that had been revealed by God in Christ, and governments were not necessary to teach people what they already knew about morality.

Locke said that at birth we are tabula rasa , commonly referred to as “blank slates.” Locke translated the phrase as “white papers.” Our family, our environment, and the revelation of God wrote on these blank slates, shaping our values from birth. The only thing our minds possessed at birth, he thought, was curiosity. Locke said, “Curiosity is nature’s instrument to correct ignorance.” This fact is why I said John Locke must have loved Peter the Great. The Russian Czar’s insatiable curiosity transformed his whole country!

To Montesquieu. Here is an analogy for you. A match is to gunpowder as Locke is to French philosophy. Locke’s ideas were conservative in England where a limited monarchy shared power with a tolerant established Church and a representative

Parliament. The ideas were radical when picked up by thinkers in a Roman Catholic despotic state. A philosopher/novelist, Voltaire, was Locke’s biggest French fan, but

Montesquieu was their best political theorist. Stay tuned for more on Voltaire, but he,

Montesquieu, and other French thinkers thought Locke was great because he was a friend of Newton, the Englishman who had wowed all of Europe. Plus, England with its political system had just beaten France with its political system in two world wars, the last of which was in the process of taking away France’s North American empire.

In the midst of this turmoil and international competition, Montesquieu came out with his major work in 1748, the Spirit of the Laws . He theorized that successful states tuned themselves to their particular circumstances. Variables involved climate, terrain, and the occupations and national character of the people being governed. Montesquieu developed a table to explain three types of governments:

Type

Despotism

Mixed Monarchy

(Britain)

National Size

Large

Medium

Climate

Hot

Temperate

Citizens’ motivation

Fear

Collective honor

Republic Small Cold Individual civic virtue

In forming this analysis, Montesquieu broke with Locke’s notion that there was one, single best way for all nations to govern themselves (obviously). He observed, interestingly, that with the increasing responsibility of the individual in a society, there was “freer” liberty. He defined liberty as, “ the ability to act as the laws permit ,” but he did acknowledge that laws needed rational reform.

Montesquieu wouldn’t acknowledge that the British had the best form of government, but he did say that Englishmen had freer liberty because of their use of separation of powers. It was Montesquieu who divided them into legislative, executive, and judicial, an idea which the United States of America would latch onto along with his concept of a system of “checks and balances.” The Founding Fathers of America read

Hobbes, Locke, and Montesquieu. These philosophers’ ideas were the intellectual impetus of both the American and French revolutions (1776 and 1789, respectively).