Len Deighton, Funeral in Berlin

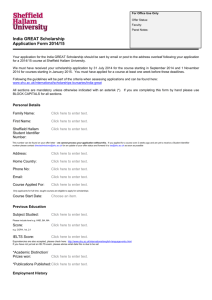

advertisement