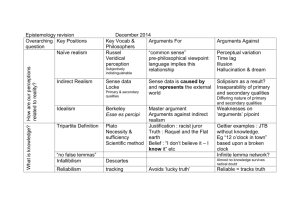

Handout 16: Berkeley I

advertisement

Lecture on Berkeley I I. Transition A. Leibniz: Theistic, focused on metaphysics and the nature of bodies. Argues that the modern, Newtonian picture of bodies is incoherent—that monads are required to explain ultimate reality, that “force” is required to explain change, and that the only way to think about force existing in a monad is as a kind of psychological force—perception and appetition. Bodies merely phenomenal. B. Recall also occasionalism. Malebranche’s realism is strange because it leaves the external objects out there, at least with their primary qualities. Berkeley does away with the extra level of reality, motivated at least in part by Occam’s razor. C. Finally, consider Locke’s view. First, he is an empiricist, someone who wants to ground all of our knowledge, and indeed all of our ideas, in the simple ideas that we get through sensation and reflection (introspection). Second, the distinction between the primary and secondary qualities, moreover, had taken hold in modern philosophy and become the dominant picture. Eliminitivism vs. Reductionism. *Berkeley is going to say that Locke’s philosophy leads to skepticism and atheism. Skepticism because on Locke’s own empiricist principles we can’t prove the existence of external material objects. Atheism because there is no clear need for God in the system, and Locke’s own arguments for God’s existence are weak. F. So Berkeley is going to give us an occasionalist, empiricist idealism which is meant to refute skepticism and atheism AND be in keeping with common sense. This rhetorical strategy, of aligning himself with common sense or “The Vulgar,” is brilliant, since that is typically exactly what people accuse the idealists of not doing, and not being able to do. II. Life (1685-1753) III. Some arguments that we would have confronted in the Dialogues A. Start with Relativity Arguments regarding Secondary Qualities 1. What is the object of our perception? Sensible qualities of objects. 2. Are sensible qualities in the mind, or in the object? 3. An argument a) The real properties of an external object cannot change without the occurrence of a change in the object itself. b) The sensible qualities I perceive can change without the occurrence of a change in the object itself. 1 c) Thus, the sensible qualities I perceive are not the real properties of an external object. 4. Defending (3b) a. Consider colors: If the surrounding lighting is altered, or if I have jaundice, the sensible color qualities that I perceive change, and if I get up really close the color disappears, but all this occurs without there being a change in the object itself. b. All other secondary qualities--sounds, tastes, smells--are also susceptible to relativity in this way. So these sensible qualities are not real properties of the external object. They are merely sensations—i.e., ideas in the mind. c. If they are merely ideas, then Berkeley suggests that they cannot exist in matter, which is supposed to be an unthinking corporeal substance. Again, these qualities are sensations, and sensations are ideas, and ideas exist only in minds. Something that doesn’t think (i.e. matter) can’t have ideas. d. Riposte: Make the primary/secondary quality distinction and become Lockean reductionists. B. Absurdity arguments against reductionism. You end up with the absurd conclusion that, e.g., sounds are vibrations in the air—so real sounds can be felt or seen, but not heard! C. Moreover, the Relativity argument also applies to primary qualities. Consider figure. 1. Presumably a mite sees its own foot, and sees it to be rather large, whereas we can only see it under a microscope, and even then not very large. Moreover, visible figure changes as we move closer to a thing. 2. So it looks like the relativity argument applies also to extension and figure as sensible qualities. B makes analogous arguments for motion and solidity. 3. Why do we privilege taking a ruler up to the tabletop and measuring it? Because touch reinforces sight? If so, then here is where B’s arguments against assuming that it is self-evident that touch and sight give us the same thing play an important role. *Molyneaux problem: Locke admits that the man blind from birth would not know by sight the difference between a globe and a cube. (291b) *Likewise, we only by custom take ourselves to be touching the “same thing” as we are seeing; the senses don’t actually tell us that they are the same thing. “A man no more sees and feels the same thing, than he hears and feels the same thing” (New Theory of Vision, section 47). 2 *Why privilege the way the ruler looks to you when you hold it that way (i.e. in the holding it up to the table and measuring way)? 4. So all we perceive are ideas, and ideas exist only in minds. If we perceive bodies at all, as everyone thinks we do, then bodies must just be collections of ideas in minds. D. The inseparability argument (cf. 426b; pp. 472-3). 1. A thought experiment: “For my own part, I evidently see that it is not in my power to frame an idea of body extended and moved, but I must in addition give it some color or other sensible quality which is acknowledged to exist only in the mind” (pp. 472-3). 2. Inseparability in thought implies inseparability in fact (cf. p. 426b). 3. Therefore the “primary” qualities exist only where the “secondary” qualities do (“in the mind and nowhere else”). *But are we really unable to conceive of primary qualities existing apart from all secondary qualities as the inseparability argument suggests? a. Imagine a red circle, a blue circle, a green circle… b. They’re all in the same shape. c. Now can we conceive of something possible by thinking, “it’s like these in shape but without any color”? d. Does the concept of similarity, without any possible image, establish possibility? e. Do we get by touch an image of something like the colored circles in shape but without any color? 1) B says no: “A man no more sees and feels the same thing, than he hears and feels the same thing” (New Theory of Vision, section 47). 2) He argues that what is common to a “visible square” and a “tangible square” is too abstractly mathematical to constitute likeness (New Theory, section 142-3). 3) This is an interesting, deep, and complex issue… 5. Perhaps we can appeal not to an idea of a particular set of primary qualities existing apart from all secondary qualities, but rather to the general notion or abstract general idea of extension, motion, size, etc. (425b-426b). 6. Against abstract ideas (see Intro to the Principles) 3