Philosopher of the Month: John Locke

advertisement

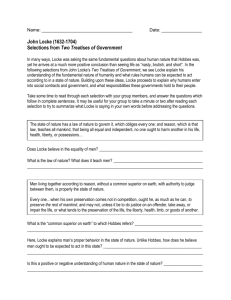

Philosopher of the Month: John Locke It is perhaps a measure of John Locke's greatness that nowadays his views seem prosaic commonplaces. The force of his arguments and the influence of his conclusions were so powerful as to become entwined in the warp and weft of western thinking. It was not always so. In his own time, Locke was a revolutionary. Locke crammed an awful lot into one lifetime: Oxford Don, physician, meteorologist, chemist, horticulturist, secretary, tutor, civil-servant, political advisor, diplomat, theologian, exile and, once, an enemy of the state, implicated in a plot to assassinate the king. But he is most well known as an epistemologist and political philosopher. One of the most crucial aspects of Locke's thought was his challenge to traditional political and religious authority. This finds its expression in two of his most influential works: the Essay concerning Human Understanding (1690) and the Two Treatises of Government (1690). The Essay commenced with a lengthy diatribe against innatism. This was the view that there were certain innate principles imprinted upon the brain of every human as guides to both practical and ethical life. Although this now seems massively anachronistic (thanks largely to Locke's influence) these were manifest truths in the middle of the seventeenth century. Even Descartes resorted to innate ideas to bridge the gap from mind to world. It has been remarked that whilst Descartes was the first modern philosopher, Locke had the first modern mind. His rejection of innatism is a reflection of this fact. The doctrine had been used as a tool for the dogmatist to inculcate obedience. Locke's dismissal of this view paved the way for the legitimacy of individual intellectual integrity. As Locke had vanquished dogmatism in epistemology, so he attacked it in politics. The first of the two Treatises was designed to show that the divine right of kings was nonsense. It had been maintained that kings had authority since they were direct descendants of Adam who, as owner of the earth, had sovereign power over it. Locke produced many criticisms of this, not least that it was implausible as a matter of fact. More importantly, however, he showed that ownership had nothing to do with sovereignty - the fact that I own some land does not give me a power of life or death over those standing on it. In the place of these traditional views Locke put forward more measured alternatives. In the Essay he proposed to provide a map of the mind's faculties through introspection. It was his hope to set the limits of human knowledge, faith and opinion, so as to prevent fruitless disputes on topics the understanding was not fit to deal with. The most famous and influential of Locke's findings was that all knowledge was founded on and derived from experience. This thought found expression in Locke's ‘new way of Ideas’. There were two sources of ideas: sensation and reflection. It was these combined, compared and contrasted which provided the basis for all human knowledge. It was these also that fixed the boundaries of human thought, and provided some of Locke's most controversial conclusions. Locke held that simple ideas enter the mind single and unmixed, thus all complex ideas are products of the understanding's faculty of compounding. Consequently complex ideas of objects were merely stuck-together simple ideas. But what of the substance of things? For Locke, our idea of substance is the something, we know not what, which we suppose to glue the causes of our ideas together. This, of course, was anathema to both the Aristotelian and Cartesian traditions which placed substance at the heart of their respective systems. For Locke, the idea was merely a peculiar place-holder with no correlate in our experience. Locke's addition to the subject-matter of philosophy was the issue of personal identity. By rejecting a notion of contenful substance, Locke had to provide another criterion of personal identity over time, and did so in the form of psychological continuity, mainly of memory: I am the same as my younger self if I can recall the actions of this more youthful me. Although his solution fades in and out of fashion, the problem itself remains an enduring philosophical issue. In the political arena Locke is seen as the founder of the modern liberal tradition, with its emphases on limited government by social contract and the right of the people to overthrow a ruler. Locke's arguments were directed against not only traditionalists, but also the extremism of Hobbes' Leviathan. The Lockean society with its emphasis upon consent and toleration is not only more realistic, but provides the model for modern democracy and, it has been argued, even supplies the blueprint for the American Constitution. There is a very great deal more to John Locke. He wrote on many subjects and founded several new schools of thought. Nevertheless, it is as a philosopher that Locke will be remembered. A philosopher, moreover, who is once more beginning to regain the recognition he so much deserves.