Week 15:IBS

advertisement

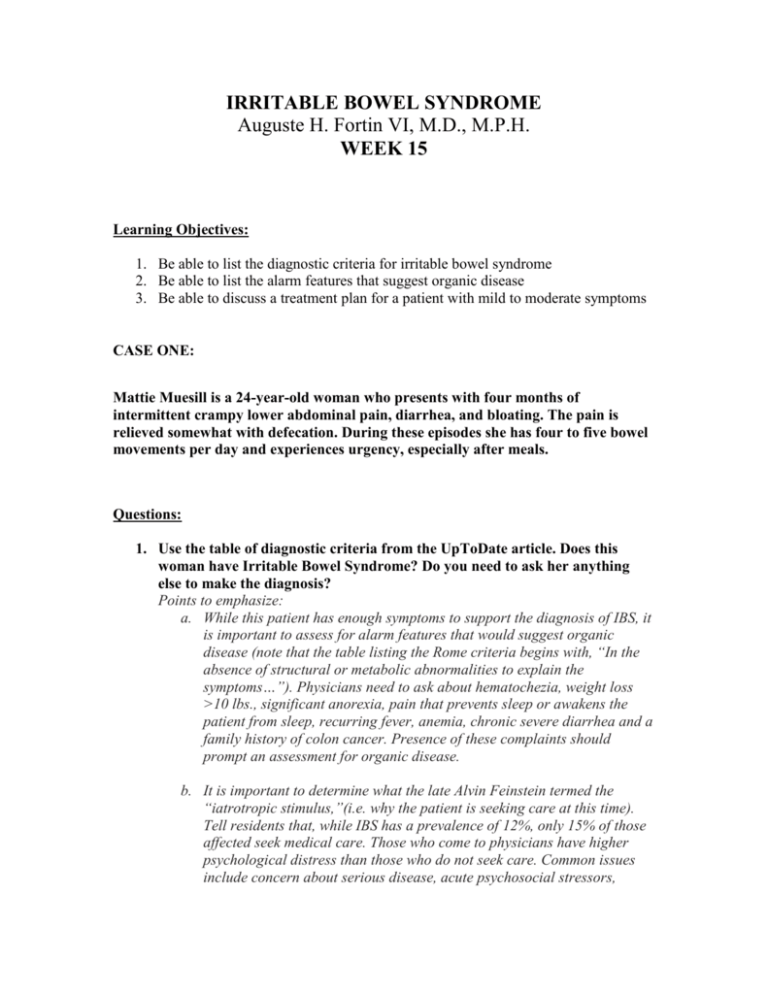

IRRITABLE BOWEL SYNDROME Auguste H. Fortin VI, M.D., M.P.H. WEEK 15 Learning Objectives: 1. Be able to list the diagnostic criteria for irritable bowel syndrome 2. Be able to list the alarm features that suggest organic disease 3. Be able to discuss a treatment plan for a patient with mild to moderate symptoms CASE ONE: Mattie Muesill is a 24-year-old woman who presents with four months of intermittent crampy lower abdominal pain, diarrhea, and bloating. The pain is relieved somewhat with defecation. During these episodes she has four to five bowel movements per day and experiences urgency, especially after meals. Questions: 1. Use the table of diagnostic criteria from the UpToDate article. Does this woman have Irritable Bowel Syndrome? Do you need to ask her anything else to make the diagnosis? Points to emphasize: a. While this patient has enough symptoms to support the diagnosis of IBS, it is important to assess for alarm features that would suggest organic disease (note that the table listing the Rome criteria begins with, “In the absence of structural or metabolic abnormalities to explain the symptoms…”). Physicians need to ask about hematochezia, weight loss >10 lbs., significant anorexia, pain that prevents sleep or awakens the patient from sleep, recurring fever, anemia, chronic severe diarrhea and a family history of colon cancer. Presence of these complaints should prompt an assessment for organic disease. b. It is important to determine what the late Alvin Feinstein termed the “iatrotropic stimulus,”(i.e. why the patient is seeking care at this time). Tell residents that, while IBS has a prevalence of 12%, only 15% of those affected seek medical care. Those who come to physicians have higher psychological distress than those who do not seek care. Common issues include concern about serious disease, acute psychosocial stressors, anxiety, somatization, and depression. A history of physical or sexual abuse is about four times more common among patients with functional gastrointestinal disorders, such as IBS, than among patients with organic gastrointestinal disorders such as colitis or unaffected controls.1,2 CASE ONE CONTINUED: Mattie recalls that her symptoms began after a new boyfriend became violent towards her. He was verbally abusive and forced her to have sex once. She broke up with him last month, but he continues to call. She does not have symptoms of depression but, does feel anxious and “on edge.” She had similar bowel symptoms in high school, usually around the time of final exams and when she performed in school plays. She denies fever, weight loss or blood in her stools. She takes an oral contraceptive pill and a multivitamin. Her family history is negative for colon cancer, colitis, lactose intolerance, and sprue. She has neither traveled abroad nor gone wilderness camping. Her roommate is not ill. Physical Exam: Temperature 98.7, BP 124/68, pulse 82. Physical examination is normal except for somewhat hyperactive bowel sounds and tenderness in the LLQ to deep palpation. There is no rebound tenderness or guarding. Rectal exam reveals brown, guaiac negative stool. Pelvic exam is normal. 2. Can you make a diagnosis now? Mattie’s presentation is classic for IBS, particularly since she is a woman (IBS is twice as prevalent in women) and can link symptoms to stress. She has the diarrhea-predominant type. Emphasize to residents that alternating diarrhea and constipation and constipation-predominant are also common presentations. A biopsychocosocial approach is particularly helpful in disorders like this, to help avoid the urge to “rule-out” all organic diseases before settling on a non-organic diagnosis. Ask residents what other diagnoses they are entertaining. The lack of alarm features makes serious illness like colon cancer, colitis, and sprue highly unlikely. I would want to be sure that Mattie did not consume excessive amounts of sorbitol (in breath mints, for example), caffeine, or magnesium-containing antacids, which can cause diarrhea. I would ask about symptoms for and focus my physical examination on signs of hyperthyroidism. (Mattie’s history and exam were not consistent with this diagnosis.) I would feel comfortable forgoing further diagnostic testing in this classic case, but some “experts” (remind residents that these are often subspecialists who see a skewed population of patients and/or who do not subscribe to the biopsychosocial model) recommend CBC, chemistry panel, TSH and three stools for O & P. (Please stress to residents that, in Mattie’s case, a CBC would be unlikely to contribute useful diagnostic data, absent a fever or pale conjunctivae; hyperthyroidism severe enough to cause diarrhea would be exceedingly rare given her pulse rate of only 82, lack of lid lag or tremor; and stool for O & P without a history of travel or sick contacts is rarely diagnostic). In patients with chronic diarrhea (not Mattie) a 24-hour collection of stool for weight can help rule out osmotic or secretory diarrhea due to malabsorption, since stool weight >300gm is rare in IBS. Testing for celiac sprue might be considered in patients at increased risk (family history, type 1 diabetes, northern European ancestry). Fortunately even the experts agree that routine colonoscopy/sigmoidoscopy and biopsy in patients with presentations consistent with IBS are not warranted. When symptoms are not associated with stress (or if the patient refuses to entertain such an association), a firm diagnosis can be more difficult. If Mattie’s symptoms did not improve after 4-8 weeks of treatment, I would reassess and pursue appropriate tests. 3. Assuming that Mattie has IBS, what is your approach to treatment? A supportive doctor-patient relationship and education about the chronicity and benign nature of IBS is important. Dietary modifications, such as decreasing caffeine, fat, and sorbitol are reasonable. I would also consider a trial of lactosefree diet and the possibility of fructose-intolerance. An exercise program may help relieve symptoms. Since she doesn’t have constipation, adding fiber to her diet may not be useful. Psychological therapies are recommended in this case, with the strong connection to a stressful event. Diarrhea and pain respond better than constipation. Loperamide will reduce diarrhea but not pain. It is safe for long-term use. To treat pain (but not diarrhea or constipation) an antispasmodic, with or without an anxiolytic, may be needed; Table 1 in the Mertz article lists them. The article states that dependence or recreational use of the antispasmodic/anxiolytic combination agents are rare because the anticholinergic component causes unpleasant side effects at higher doses. My preference is to encourage anxious patients to enter into psychotherapy to address the cause of anxiety. Low-dose TCAs are very useful for pain and diarrhea, even in the absence of depression; they can be used along with antispasmodics if needed. SSRIs are not effective. The serotonin-3 receptor antagonist alosetron may have modest benefit in severe diarrhea-predominant IBS. It has only been compared to placebo (and one antispasmodic not available in the US); whether alosetron is better than standard therapies (antidiarrheal, antispasmodic, anticholinergic) or would provide additional benefit when added to them is not known. It is expensive, $366$723/month at www.drugstore.com. Physicians need to participate in a training program before prescribing it because of the risk of ischemic colitis. Of course, addressing intimate partner violence is critical. This would include assessing her psychosocial support, assuring that Mattie has a plan for her safety and providing numbers for domestic violence hotlines and women’s shelters. 4. What treatments would you use if Mattie had constipation-predominant IBS? The non-specific treatments in question 3 would also apply here. Fiber would play a role in this instance, as would magnesium or phosphate salts or PEGbased laxatives; chronic use is OK. Avoid stimulants cathartics such as bisacodyl and senna. The serotonin-4 receptor antagonist tegaserod may have a modest benefit in severe cases of constipation-predominant IBS; it is only FDA-approved for 12-week’s use. There is no evidence that it is better than standard therapies (fiber, antispasmodics) because it has only been tested against placebo. It is expensive, $154.00/month at www.drugstore.com. References: 1. Mertz, HR. Irritable bowel syndrome. New England Journal of Medicine. 2003; 349:2136-46. 2. Table 3 from: Chun AB, Desautels S, Wald A. Clinical manifestations and diagnosis of irritable bowel syndrome. UpToDate v. 12.3 Additional References: 1. Drossman DA, et al. Sexual and physical abuse in women with functional or organic gastrointestinal disorders. Ann Intern Med. 1990; 113:828-833. 2. Drossman DA, et al. Sexual and physical abuse and gastrointestinal illness. Review and recommendations [see comments]. Ann Intern Med. 1995; 123:782794.