Althea`s research notes – Roman and Anglo Saxon periods

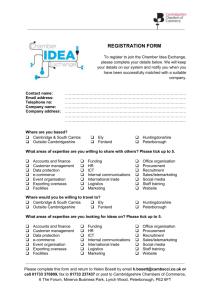

advertisement

Althea’s Research Notes – Roman and Anglo Saxon Periods A History of Huntingdonshire by Michael Wickes (1985 revised 1995 – Published by Phillimore). Roman Romano-British settlements have been identified at Wyton, Wistow, Woodhurst and Broughton on the upland area that forms a peninsular between the Fens and the Ouse valley. Romano-British settlers probably cleared much of this forested region for farming. Many local place names are associated with woodland e.g. Upwood, Woodwalton, Woodhurst and Oldhurst. The tribe called ‘Hurstingas’ (Hyrstingas), meaning ‘forest dwellers’, lived around the Ouse valley and on the wooded uplands and they are commemorated in the hundred-name Hurstingstone. The area probably reverted to forest during the early Anglo-Saxon era. Anglo Saxon Anglo-Saxon settlements were organised in a series of large estates, each estate being the size of several modern parishes. These were fragmented into smaller units at a later date. The boundaries of these smaller units, or manors, were often used by the church to mark out boundaries of the later ecclesiastical parishes and so have been preserved into the modern era. The fragmentation of the large estates was caused by landlords rewarding followers with parcels of land, a process commemorated in the wording of some charters. One of the larger estates was centred upon the manor of Wistow, a settlement that was known as ‘Kingston’ before it was granted to Ramsey Abbey in a charter dated 974. This is the first recorded appearance of the village name Wistow. The charter also noted that Wistow had two ‘berewicks’ (daughter settlements that still retain some link with their parent) at Little Ravely and Bury. This royal estate was obviously granted to the abbey as a fully developed agricultural unit, not as a piece of forested land to be cleared by the monks. (‘Stow’ derives from an Anglo-Saxon word for ‘holy place’). The Benedictine abbey at Ramsey was almost the first monastic institution to be founded within the borders Huntingdonshire in 974. The abbey was granted considerable estates within Huntingdonshire, making it the fourth wealthiest monastery in England and the greatest landowner in the county by the time of the Domesday survey. The monastery was also granted a ‘banlieu’, or liberty, covering Ramsey itself, Bury, Upwood and part of Wistow and Great Ravely. This gave the abbot almost monarchical powers over the inhabitants of the liberty. The Victoria History of the County of Huntingdonshire Volume II Edited by William Page, Granville Proby & S. Inskip Ladds 1932 reprinted 1974 (My comments are in italics). (N. B. Much of the History of Wistow written by Mac Simpson in May 1977 seems to have been taken from this book, so I have not included this section here). Political History Celtic and Roman The district now known as Huntingdonshire was originally either forest or fenland and consequently was sparsely inhabited. The Fens, which acted as, a barrier to the invader from the east, tended to retard the development of the country, and although the prehistoric immigrants left some traces of their occupation, their influence was apparently only passing. The land was probably a part of the territory of the Celtic kingdom of the Catuvellauni, whose seat of government was at Verulanium near St. Albans. Under Roman organisation the important pottery trade was developed along the valley of the Nene, the reclamation of the fertile fenland was possibly begun and the uplands cultivated for corn. Anglo Saxon After the withdrawal of the Roman legions in the early part of the 5th century the Britons lost the power of organisation, which they obtained during the four centuries of Roman domination. Gildas records what befell the Britons in the west of England, but little of the east. The Britons of the southeastern Midlands were being assailed and driven out by the West Saxons from the southwest, by the East Angles from the east and by the Middle Angles from the northeast. What is now Huntingdonshire was incorporated into the territory of the Middle Angles, which became absorbed by the Mercians before the middle of the 7th century. There is no doubt that the land of the Middle Angles was part of the kingdom of Mercia about 675, when the Tribal Hidage was compiled. This document shows the hidage for each of the 18 or more tribal areas or districts of independent communities of which Mercia was composed. Those that concern Huntingdonshire were the lands of the Spalda, with 600 hides in the southern part of the county, and the lands of the Sweodora with 300 hides; the Herstina, a tribe with 600 hides, which is entered on one copy of the document, is thought to have given its name to the hundred of Hurstinstone. The important tribe of the Gyrwas that occupied the fenland may have spread southward into the county and possibly absorbed some of the less important tribes already settled there. This district continued part of the kingdom of Mercia until the Danish invasion of the 9th century. Vikings It suffered with the rest of Mercia during the early Viking raids, but to a lesser degree than its northern and eastern neighbours. In 870 the Danes seem to have overrun all of Mercia and desultory fighting continued until 874, when they drove King Burhred overseas and Mercia came under the rule of Ceolwulf. In 877 a treaty was made between Ceowulf and the Danes, whereby Ceowulf took the western, smaller part of Mercia and the Danes held the eastern part including Huntingdon, Northampton, Bedford and Cambridge. (Alfred The Great was King of Wessex at this time. Edward the Elder was his son). Danish rule became completely established throughout the Eastern Midlands by the confederation of five boroughs of Leicester, Lincoln, Derby, Nottingham and Stamford. Southward and eastward the towns of Colchester, Cambridge, Huntingdon, Buckingham and Bedford also became centres of Danish government, where garrisons were maintained and tribute was paid. Edward the Elder recovered Buckingham in 918 and a year later he took Bedford. In 921 the Danes, to recover the territory collected a great host from East Anglia with a contingent from Huntingdon, which they left deserted. The Danes were driven back by the English under Edward the Elder. He proceeded to march against the fen district and the remnant of the people he found at Huntingdon sought his peace and protection, as eventually did the whole of East Anglia. A period of comparative peace followed in the middle of the 10th century when the monasteries were founded, one of them being the Abbey of Ramsey in 969, which later held a prevailing interest in the county. Turmoil ensued again in the days of Ethelred the Unready, 978-1016, and by 1011 the Danes had again overrun East Anglia and the shires of Essex, Middlesex, Oxford, Cambridge, Hertford, Buckingham, Bedford, half of Huntingdon and much of Northampton. The Dane, Cnut, ascended the throne in 1016 and attempted to settle the fen country by making a road from Peterborough to Ramsey and endowing the fenland monasteries with property in Huntingdonshire. By this time Huntingdonshire had become fully organised as a shire, with its earl or alderman, sheriff and shire court. According to Richard, a monk of Ely writing in the early half of the 12th century, in his ‘Historia Eliensis’, Huntingdon was organised as a shire comprising 6 hundreds before the third quarter of the 10th century and had an earl in the first quarter of that century. The first references to the word Huntingdonshire, however, occur in a charter of tainted origin dated 948, by Eadred to Croyland Abbey; in the narrative of the dedication of Ramsey church in 991; and in the list of counties overrun by the Danes in 1011. An Atlas of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire History edited by Tony Kirby and Susan Oosthuizen (Published 2000 by Anglia Polytechnic University) Anglo Saxon According to the Anglo Saxon Chronicle, East Anglia was settled by a Danish army under King Guthrum in 881. Alfred the Great was the King of Wessex at this time. Guthrum’s kingdom became known as the Eastern Danelaw. At the same time the region to the west was occupied by four satellite armies, each commanded by an earl. The Danish warriors of these outer territories mustered at fortified centres which developed in due course into the towns of Cambridge, Huntingdon, Bedford and Northampton. These areas settled by their respective armies became known in later years as shires. Wistow was in the area controlled by the Danish Army of Huntingdon 880-917. Guthrum’s kingdom was completely independent and developed its own legal administrative and economic structure and paid no tribute to the West Saxon Crown. Although Guthrum nominally accepted the Christian faith, most of the new army settlers were illiterate adventurers who retained their pagan beliefs and culture. Monasteries were plunderd and abandoned and the diocesan structure swept away. The earls, although accepting Guthrum’s overall suzerainty, were autonomous in their internal administration. They each established their own mint and distinctive coinage. Throughout the earldoms, as in the rest of the Danelaw, there was a revolution in land tenure in which the former Anglian landowners forfeited their estates, becoming subservient to the Danish conquerors. The Danes probably instituted their own system of strip cultivation of open fields, which entailed a considerable degree of cooperation between the owners of individual strips. This would be best achieved by concentrating the bulk of the population, Anglian and Danish, in newly established nucleated communities which replaced the earlier pattern of settlement of scattered hamlets and farmsteads. This may well have been the principal motivation for the creation of villages, each farming an area with its own boundary and developing a network of lanes and footpaths for communication with neighbours. By the time of the Norman Conquest there were a little over 80 villages in Huntingdonshire and 160 in Cambridgeshire. It is probable that many of these were created during the period of the Danish autonomy. The Danish settlement of Huntingdonshire and Cambridgeshire was one of upheaval in exploitation of land and the way of life of the former Anglo Saxon inhabitants. The Danish Earls established fortified enclosures for the minting of their coinage and as residences for themselves and leaders of lesser status known as holds. Wistow was one of these smaller defended enclosures for the Danish Huntungdonshire Army. During the initial share-out of land each hold was allotted one or more of the large multiple estates which had characterised land ownership during the later Anglian period. Under Danish rule these became known as sokes. Within sokes individual parcels of land were given to members of the Danish Army, who became known as sokemen. The sokemen were able to sell their holding and an active land market developed. By 1066 over 30% of the Cambridgdeshire arable was still under sokeland tenure. The administration of each shire was effected at regular gatherings of its settlers at the shire town, where decisions were taken concerning army service, support of the Earl and maintenance of defences. For local administration the shire was subdivided into districts known as wapentakes, each having well defined boundaries and possibly these were coterminous with the later hundredal groupings. Settlers within an individual wapentake would assemble every few weeks at one of several open-air meeting places, where land transactions and trials of malefactors took place before the witness of the whole assembly. As well as defensive towns, Huntingdon and Cambridge developed as commercial centres. There appears to have been little contact with those parts of England still under West Saxon and Mercian rule and a new pattern of trading with the rest of the Danelaw was established via Ermine Street, the so-called Via Devana, Icknield Way and branches of the Ouse. The Fenland economy was based on turbaries, fishing, fowling, pasturing of livestock and harvesting of reeds for thatching. The overall picture is of innovation and bustling activity and because of the successful agrarian system, the Danelaw shires were more prosperous than their English counterparts in Wessex and Mercia. This difference in prosperity may be one of the motivating factors for a series of campaigns mounted in 917 by King Edward the Elder and his sister Aethelflaed, Lady of the Mercians (children of Alfred the Great), for recovery of parts of the Danelaw south of Welland. After defeating the Danish Army under Earl Toglos decisively at Huntingdon and Wistow, Edward accepted the surrender of the Danes of Cambridgeshire and the 37 year autonomy of the two shires came to an abrupt end.