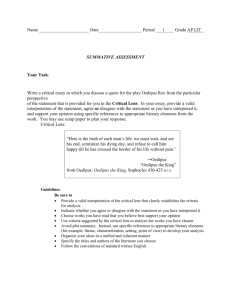

The Concept of the Hero in Greek Civilization

advertisement