here - British Society for Antimicrobial Chemotherapy

advertisement

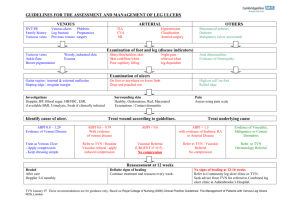

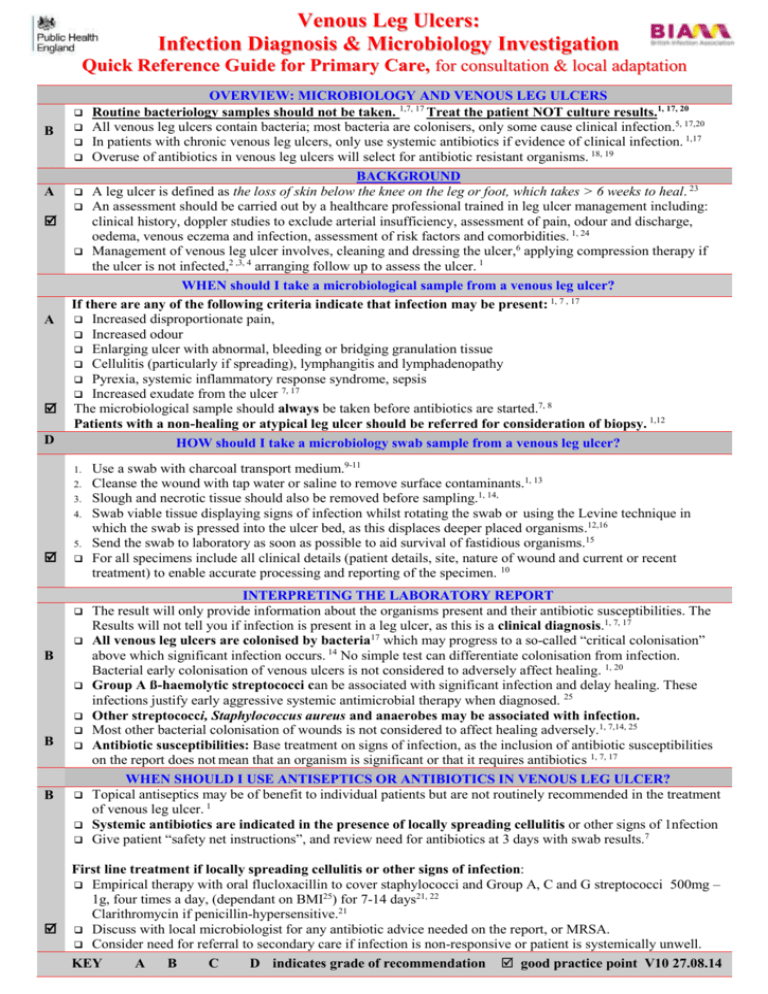

Venous Leg Ulcers: Infection Diagnosis & Microbiology Investigation Quick Reference Guide for Primary Care, for consultation & local adaptation OVERVIEW: MICROBIOLOGY AND VENOUS LEG ULCERS Routine bacteriology samples should not be taken. 1,7, 17 Treat the patient NOT culture results.1, 17, 20 All venous leg ulcers contain bacteria; most bacteria are colonisers, only some cause clinical infection.5, 17,20 In patients with chronic venous leg ulcers, only use systemic antibiotics if evidence of clinical infection. 1,17 Overuse of antibiotics in venous leg ulcers will select for antibiotic resistant organisms. 18, 19 BACKGROUND A leg ulcer is defined as the loss of skin below the knee on the leg or foot, which takes > 6 weeks to heal. 23 An assessment should be carried out by a healthcare professional trained in leg ulcer management including: clinical history, doppler studies to exclude arterial insufficiency, assessment of pain, odour and discharge, oedema, venous eczema and infection, assessment of risk factors and comorbidities. 1, 24 Management of venous leg ulcer involves, cleaning and dressing the ulcer,6 applying compression therapy if the ulcer is not infected,2 ,3, 4 arranging follow up to assess the ulcer. 1 WHEN should I take a microbiological sample from a venous leg ulcer? If there are any of the following criteria indicate that infection may be present: 1, 7 , 17 Increased disproportionate pain, Increased odour Enlarging ulcer with abnormal, bleeding or bridging granulation tissue Cellulitis (particularly if spreading), lymphangitis and lymphadenopathy Pyrexia, systemic inflammatory response syndrome, sepsis Increased exudate from the ulcer 7, 17 The microbiological sample should always be taken before antibiotics are started.7, 8 Patients with a non-healing or atypical leg ulcer should be referred for consideration of biopsy. 1,12 HOW should I take a microbiology swab sample from a venous leg ulcer? B A A D 1. 2. 3. 4. 5. B B B Use a swab with charcoal transport medium.9-11 Cleanse the wound with tap water or saline to remove surface contaminants.1, 13 Slough and necrotic tissue should also be removed before sampling.1, 14, Swab viable tissue displaying signs of infection whilst rotating the swab or using the Levine technique in which the swab is pressed into the ulcer bed, as this displaces deeper placed organisms.12,16 Send the swab to laboratory as soon as possible to aid survival of fastidious organisms.15 For all specimens include all clinical details (patient details, site, nature of wound and current or recent treatment) to enable accurate processing and reporting of the specimen. 10 INTERPRETING THE LABORATORY REPORT The result will only provide information about the organisms present and their antibiotic susceptibilities. The Results will not tell you if infection is present in a leg ulcer, as this is a clinical diagnosis.1, 7, 17 All venous leg ulcers are colonised by bacteria17 which may progress to a so-called “critical colonisation” above which significant infection occurs. 14 No simple test can differentiate colonisation from infection. Bacterial early colonisation of venous ulcers is not considered to adversely affect healing. 1, 20 Group A ß-haemolytic streptococci can be associated with significant infection and delay healing. These infections justify early aggressive systemic antimicrobial therapy when diagnosed. 25 Other streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus and anaerobes may be associated with infection. Most other bacterial colonisation of wounds is not considered to affect healing adversely.1, 7,14, 25 Antibiotic susceptibilities: Base treatment on signs of infection, as the inclusion of antibiotic susceptibilities on the report does not mean that an organism is significant or that it requires antibiotics 1, 7, 17 WHEN SHOULD I USE ANTISEPTICS OR ANTIBIOTICS IN VENOUS LEG ULCER? Topical antiseptics may be of benefit to individual patients but are not routinely recommended in the treatment of venous leg ulcer. 1 Systemic antibiotics are indicated in the presence of locally spreading cellulitis or other signs of 1nfection Give patient “safety net instructions”, and review need for antibiotics at 3 days with swab results.7 First line treatment if locally spreading cellulitis or other signs of infection: Empirical therapy with oral flucloxacillin to cover staphylococci and Group A, C and G streptococci 500mg – 1g, four times a day, (dependant on BMI25) for 7-14 days21, 22 Clarithromycin if penicillin-hypersensitive.21 Discuss with local microbiologist for any antibiotic advice needed on the report, or MRSA. Consider need for referral to secondary care if infection is non-responsive or patient is systemically unwell. KEY A B C D indicates grade of recommendation good practice point V10 27.08.14 This guidance was produced in 2006 by the South West GP Microbiology Laboratory Use Group in collaboration with the Association of Medical Microbiologists, GPs and experts in the field. This guidance was reviewed and updated in 2014 by Dr Gerry Morrow at Clarity Informatics with input from Dr Cliodna McNulty, Philippa Moore, Professor David Leaper and Jacqui Fletcher (Cardiff University), ARHAI; BSAC; BIA; GPs and experts in the field and is in line with other UK GP guidance including Clinical Knowledge Summaries. The guidance is designed to be used by Primary Care clinicians; it aims: To provide a simple, effective, economical and empirical approach to the treatment of common infections. To minimise the emergence of bacterial resistance in the community. This guidance is based on the best available evidence but professional judgement should be used and patients should be involved in the decision. Local adaptation: We would discourage major changes to the guidance but the Word format allows minor changes to suit local service delivery and sampling protocols. To create ownership agreement on the guidance locally, dissemination should be taken forward in close collaboration between primary care clinicians, laboratories and secondary care providers. GRADING OF GUIDANCE RECOMMENDATIONS: The strength of each recommendation is qualified by a letter in parenthesis. Study design Recommendation grade Good recent systematic review of studies A+ One or more rigorous studies, not combined A- One or more prospective studies B+ One or more retrospective studies B- Formal combination of expert opinion C Informal opinion, other information D References 1. SIGN Management of Chronic Venous Leg Ulcers a national clinical guideline 120. August 2010 Available from: http://www.sign.ac.uk/pdf/sign120.pdf. A detailed guideline providing evidence based recommendations on the management of venous leg ulcers. SIGN outlines the prevalence as follows “chronic venous leg ulceration has an estimated UK prevalence of 0.1% to 0.3% prevalence increases with age. 1.7% of the population over 65 years are affected.” The guidance provides advice on assessment of the leg, the use of dressings and compression treatments and withholding systemic antibiotics without clear clinical need. It gives a clear rationale on use of bacteriological sampling and removal of necrotic tissue before such sampling. The advice from SIGN on when to take a bacteriological swab is that “in the absence of clinical signs of infection there is no indication for routine bacteriological swabbing of venous ulcers.” Clinical signs of infection are defined as “cellulitis, pyrexia, and increased pain, rapid extension of area of ulceration, malodour or increased exudate”. SIGN recommend that ulcerated legs should be “washed normally in tap water”. SIGN also recommend that Specialist leg ulcer clinics are recommended as the optimal service for community treatment of venous leg ulcer.”Additionally SIGN provide a list of potential topical treatments but summarises their recommendation as follows “Routine long term use of topical antiseptics and antimicrobials is not recommended.” 2. O’Meara S, Cullum NA, Nelson EA. Compression for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2009 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/19160178. This is a Cochrane review of 39 randomised controlled trials which determined to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of compression bandaging or stocking systems in the treatment of venous leg ulceration. Overall, the authors concluded that compression bandaging increases ulcer healing rates compared with no compression. Multi-component systems are more effective than single-component systems. Multi-component systems containing an elastic bandage appear more effective than those composed mainly of inelastic constituents. 3. Nelson EA, Prescott RJ, Harper DR, Gibson B, Brown D, Ruckley CV. A factorial, randomized trial of pentoxifylline or placebo, four-layer or single-layer compression, and knitted viscose or hydrocolloid dressings for venous ulcers. J Vasc Surg 2007; 45(1):134-41.Available from: http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0741521406017484. This is a report of a randomized trial which found that patients with venous ulcers treated with four-layer compression are significantly more likely to heal than those treated with an adhesive, single-layer bandage. 4. Moffatt CJ, McCullagh L, O’Connor T, Doherty DC, Hourican C, Stevens J, et al. Randomized trial of four-layer and two-layer bandage systems in the management of chronic venous ulceration. Wound Repair Regen 2003; Produced August 2006. Reviewed July 2014.533569787 For Review ….. 2017 11(3):166-71. Abstract available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/12753596 This report of a randomized trial concluded that four-layer bandage offers advantages over the two-layer bandage in terms of reduced withdrawal from treatment, fewer adverse incidents, and lower treatment cost. 5. O’Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ovington LG. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane database of Systematic Reviews 2010; Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18254024. This is a Cochrane review of 22 trials established to determine the effects of systemic, topical antibiotics and antiseptics on the healing of venous ulcers. After analysis of these papers the authors conclude that there is no existing evidence to support the routine use of systemic antibiotics to promote healing in venous leg ulcers. Additionally, they assert that In light of the increasing problem of bacterial resistance to antibiotics, current prescribing guidelines recommend that antibacterial preparations should only be used in cases of defined infection and not for bacterial colonisation . This review has been updated in January but no new recommendations have been made as a result of the review. 6. Palfreyman SJ, Nelson EA, Lochiel R, Michaels JA. Dressings for healing venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2006; (CD001103). Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1939774/ .This is a systematic review and meta-analysis to review the evidence of effectiveness of dressings applied to venous leg ulcers. 42 studies were included in the review the results showed no statistically significant difference in terms of total ulcers healed between any of the dressing types. In particular the authors wrote that the meta-analysis of hydrocolloid dressings versus low adherent dressings had more than 700 participants. The authors then concluded that hydrocolloids confer no significant clinical benefit over simple, low adherent dressings when used beneath compression. Given the potential disadvantages of using hydrocolloid rather than a low adherent simple dressing, in terms of increased cost and greater exposure to allergens in the preservative, the simple non-adherent dressing should be preferred. 7. Clinical Knowledge Summaries. Leg ulcer – venous available from: http://cks.nice.org.uk/leg-ulcervenous#!backgroundsub:3 This site provides an overview of the current recommendations in primary care for venous leg ulcer. In particular the advice given summarises the current clinical evidence in order to aid clinical decision support in primary care. This advice covers assessment, diagnosis and treatment of venous leg ulcers. Specifically advice is given that all suspected infected venous ulcers should be swabbed before prescribing an antibiotic. 8. Finch, R.G., Greenwood, D, Norrby, S.R. and Whitley, R.J. (2010) Antibiotic and chemotherapy: anti-infective agents and their use in therapy. 8th edn. London: Churchill Livingstone. 9. Barber S, Lawson PJ, Grove DI. Evaluation of bacteriological transport swabs. Pathology 1998; 30:179-82. Abstract available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/9643502. This study evaluated various transport swabs for their ability to preserve bacteria for 24 and 48 hours. Swabs using Amies plus charcoal medium or Stuart’s medium had better recovery rates than those using Amies medium alone. 10. Public Health England UK standards for microbiology investigations available from: http://www.hpa.org.uk/SMI/pdf This is a Public Health England document outlining the standards required for processing and bacteriological investigation of skin, superficial and non-surgical wound swabs. It outlines the likely pathogens to be found in each of these investigations. It also provides detail on how to optimise results from taking a skin swab and the use of appropriate transport media.. The guidance specifically states that “.Unless otherwise stated, swabs for bacterial and fungal culture should be placed in appropriate transport medium” 11. Human RP and Jones GA. Evaluation of swab transport systems against a published standard. J Clin Pathol. 2004; 57:762-3. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1770340/ This study set out to compare three swab transport systems to provide a standard and ascertain bacterial survival after a set holding time. The authors conclude that charcoal containing media provide increased survival of bacteria. 12. Davies CE, Hill KE, Newcombe RG, Stephens P, Wilson MJ, Harding KG, Thomas DW. A prospective study of the microbiology of chronic venous leg ulcers to re-evaluate the clinical predictive value of tissue biopsies and swabs. Wound Repair and Regeneration 2007; 15:17-22. Available from: http://www.ff.ul.pt/FCT/PTDC/SAUBEB/098801/2008/Davies%20et%20al_WWR_2007.pdf . This is a prospective study which determined that wound biopsies do not contribute significantly to patient management of clinically non-infected leg wounds. Wound microflora of over 70 patients with chronic venous ulcers was examined both by swab and biopsy. The analysis provided no benefit in terms of healing outcome from these wounds. The authors conclude that careful and detailed microbiological analysis of superficial swabs taken by a standardized method may obviate the need for patients to undergo biopsy procedures. 13. Fernandez R, Griffiths R. Water for wound cleansing (Review). The Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; 1:CD003861.Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18254034 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18254034 A Cochrane review of 11 trials which determined the effects of water compared with other solutions for wound cleansing. The authors concluded that there is no evidence that using tap water to cleanse acute wounds in adults increases infection and some evidence that it reduces it. However there is not strong evidence that cleansing wounds per se increases healing or reduces infection. In the absence of potable tap water, boiled and cooled water as well as distilled water can be used as wound cleansing agents. Produced August 2006. Reviewed July 2014.533569787 For Review ….. 2017 14. Bowler PG, Duerden BI and Armstrong DG. Wound microbiology and associated approaches to wound management. Clin Microbiol Reviews. 2001; 14:244-69 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC88973/ A highly detailed paper providing evidence of that the majority of open wounds are polymicrobial. The authors assert that the progression of a colonized wound to an infected state cannot be predicted by the presence of a specific type of bacterium. With regard to infection and wound healing the authors conclude that “aerobic pathogens such as S. Aureus, P. Aeruginosa and beta-hemolytic streptococci have been most frequently cited as the cause of delayed wound healing and infection” 15. Department for transport. Transport of Infectious Substances, 2011 Revision 5. Available from: http://webarchive.nationalarchives.gov.uk/20110131174015/http://www.dft.gov.uk/426155/425453/800_300/infect ioussubstances.pdf This government document outlines the timescale for microbiological specimens and the need for reducing delays in transporting microbiological samples. 16. Gardner SE, Frantz RA, Saltzman CL, Hillis SL, Park H, Scherubel M. Diagnostic validity of three swab techniques for identifying chronic wound infection. Wound Repair Regen 2006; 14(5):548-57 Abstract available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17014666 This study examined the diagnostic validity of three different swab techniques in identifying chronic wound infection. Of the 83 wounds analysed in the study 30 (36%) were infected. The authors concluded, “Accuracy was the highest for swab specimens obtained using Levine’s technique.” 17. Grey JE, Enoch S and Harding KG Wound assessment BMJ 2008 February 4; 332(7536): 285-288 available from http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1360405/: A review article which provides a methodical mechanism for wound assessment accompanied by wound photographic examples. The specifics of diagnosis of infections within wounds including reference to increasing exudate as a factor is described. The authors explain that all open wounds are colonised but that bacteriological culture is indicated only if clinical signs of infection are present. They also define the classic signs of infection as “heat, redness, swelling and pain. Additional signs of wound infection include increased exudate, delayed healing, contact bleeding, odour and abnormal granulation tissue.” 18. Valtonen V, Karppinin L, Kariniemi AL Scand J Infect Dis Suppl. 1989; 60:79-83. PubMed PMID: 2547245. A comparative study of ciprofloxacin and conventional therapy in the treatment of patients with chronic lower leg ulcers infected with Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other gram-negative rods. Abstract available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2547245 A randomised controlled trial of twenty six elderly patients with chronic leg ulcers infected by Pseudomonas aeruginosa or other Gram negative infections. One group were given ciprofloxacin for three months, the other group received local therapy. Of the patients who received oral antibiotics 67% developed ciprofloxacin resistant strains of mainly staphylococci in comparison to 0% of the patients who did not receive oral ciprofloxacin. 19. O'Meara S, Al-Kurdi D, Ologun Y, Ovington LG, Martyn-St James M, Richardson R. Antibiotics and antiseptics for venous leg ulcers. Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews 2014, Issue 1. Art. No.: CD003557. DOI: 10.1002/14651858.CD003557.pub5.This systematic review included 45 RCTs for analysis. Five RCTs reported eight comparisons involving various systemic antibiotics. A separate analysis suggested that those receiving placebo were less likely to develop antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria compared with those given ciprofloxacin. The authors conclude, “There was some evidence to suggest that systemic antibiotics were associated with emergence of antibiotic-resistant micro-organisms compared with non-antibiotic treatment.” They also comment, “There is widespread global concern with regard to the development of antibiotic resistance, and the misuse of both systemic and topical agents. Prescribing guidelines in the UK state that such agents should not be used with chronic wounds, such as leg ulcers, except in cases of demonstrable clinical infection, and that their prescription for bacterial colonisation is inappropriate. In this review, data from two trials suggested that the emergence of antibiotic-resistant strains of bacteria occurred more often in groups receiving systemic antibiotics (ciprofloxacin) when compared with standard care or placebo.” 20. Hansson C, Hoborn J, Möller A, Swanbeck G. The microbial flora in venous leg ulcers without clinical signs of infection Repeated culture using a validated standardised microbiological technique Acta Derm Venereol. 1995 Jan; 75(1):24-30. Abstract available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/7747531 In this observational study 58 patients with venous ulcers had microbiological sampling done on four occasions during the course of the study. All ulcers contained microorganisms. No correlation was found between ulcer size and the species and amounts of microorganisms. The authors conclude, “There seems to be no indication for routinely performed culture in the absence of clinical signs of infection in venous leg ulcers.” 21. CREST Guidelines on the management of cellulitis in adults. Clinical Resource Efficiency Support Team. 2005. http://www.acutemed.co.uk/docs/Cellulitis%20guidelines,%20CREST,%2005.pdf Expert consensus is that people who have cellulitis but no signs of systemic toxicity and no uncontrolled co-morbidities can usually be managed on an outpatient basis with oral antibiotics. Flucloxacillin 500mg QDS (or clarithromycin 500mg BD for those with penicillin allergy) are suitable oral antibiotics because they cover staphylococci and streptococci, the most commonly implicated pathogens. Clindamycin 300mg QDS is also recommended as a further alternative for people with penicillin allergy. Most cases of uncomplicated cellulitis can be treated successfully with 1-2 weeks of treatment. Produced August 2006. Reviewed July 2014.533569787 For Review ….. 2017 22. British Lymphology Society Consensus Document on the Management of Cellulitis in Lymphoedema available from: http://www.lymphoedema.org/Menu3/Revised%20Cellulitis%20Consensus%202013.pdf An expert consensus statement on the management of cellulitis. The authors conclude, “If there is any evidence of Staph aureus infection e.g. folliculitis, pus formation or crusted dermatitis, then flucloxacillin 500mg 6-hourly should be prescribed. Microbiologists suggest that the use of single agent Flucloxacillin for all cellulitis covers both Streptococcal and Staphylococcal infections”. 23. Dale JJ, Callam MJ, Ruckley CV, Harper DR, Berrey PN. Chronic ulcers of the leg: a study of prevalence in a Scottish community. Health Bull (Edinb). 1983 Nov; 41(6):310-4. This definition of leg ulcer originated in this paper, the authors defined a leg ulcer as “the loss of skin below the knee on the leg or foot, which takes more than 6 weeks to heal”. 24. Simon DA, Dix FP, McCollum CN. Management of venous leg ulcers. BMJ Jun 5, 2004 328(7452): 1358-1362 Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC420292/ This is a review article which discussed the assessment, diagnosis and treatment of leg ulcers. The authors outline the range of elements that the assessment should encompass including full history, examination to identify risk factors, varicose vein assessment, and Doppler. 25. Eron LJ, Lipsky BA, Low DE, Nathwani D, Tice AD and Volturo GA. Managing skin and soft tissue infections: expert panel recommendations on key decision points. Journal of Antimicrobial Chemotherapy (2003) 52, Suppl. S1, i3–i17 DOI: 10.1093/jac/dkg466Available from: http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/content/52/suppl_1/i3.full.pdf This is a review paper written by an international expert panel, the authors note “ Streptococci can be classified into several groups; those causing skin and soft tissue infections are predominantly of groups A and B. Group A streptococci are particularly associated with necrotizing fasciitis, while group B streptococci are often the causative agents of infections in diabetic patients.”The authors list the likely colonising and infecting pathogens for specific types of skin and soft tissue infections. This paper also underlines the importance of correct dosing of antibiotics in the treatment of cellulitis. The authors explain, “Appropriate dosing is largely related to the drug concentration in tissues and body fluids and the minimum inhibitory concentration for the infecting organism. Dosing is also influenced by patient characteristics, such as body weight and renal or hepatic function.” . Produced August 2006. Reviewed July 2014.533569787 For Review ….. 2017