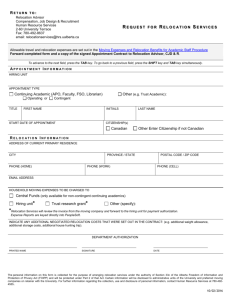

Relocation report [DOC 648KB] - Attorney

advertisement

![Relocation report [DOC 648KB] - Attorney](http://s3.studylib.net/store/data/007601586_2-dc1bf3a678f71f8c22a77d4c0c16e031-768x994.png)