Fantastic 4-Body-ings: Ideal Grotesqueness in the Comic

advertisement

1

Fantastic 4-Body-ings: Ideal Grotesqueness in the Comic-Book Culture

Christina Dokou

I. Introduction: Comics as a U.S. Cultural Index

A view of America as a culture of images,1 especially metaphors, metonymies, or

mutations of the body, is not complete unless one looks at comic books. With their

gaudily costumed superheroes sporting superpowered bodies and brains, and their

fantastic landscape allegories of America, comics sprang from a rich ancient satirical

tradition2 via cartoon strips to evolve into an independent genre. The genre reflects

pop Americana culture and history,3 aesthetic and even intellectual trends,4 a neomythology,5 and the post-millennial angst about transformations of human identity,

the layperson’s hopes and fears.6 Most comics are still searching for legitimization

because of their “unrealistic” form and theme (a fallacy explored by Thierry

Groensteen),7 their mainstream lapses into literary and artistic infantilism, and

commercial exploitation—since, in the words of Alan Moore, “It doesn’t matter how

sophisticated they are, they’re still about men with their underpants over their

trousers.”8 However, their authentic appeal and their synchronization with the

As seen in, among others, Ruth Vasey’s study on public and media images in America in

“The Media,” Modern American Culture: An Introduction, Mick Gidley, ed. (New York:

Longman, 1994): 213-38.

2 Christos Zachopoulos, “Eisagogi,” Helleniki Politiki Geloiographia [“Introduction,” Greek

Political Cartoons], Prologue by Ioannis Varvitsiotis, Christos Zachopoulos, ed., Lefkomata

series (Athens: The Constantinos Karamanlis Institute for Democracy/ Sideris Publications,

2002): 13-14.

3 See, for example, Roy Lichtenstein’s paintings, or The ‘Nam series by veteran Doug Murray,

published by Marvel in 1986.

4 As seen in the inspired combination of Plato and Nietzsche in writer Alan Moore’s and artist

Dave Gibbons’s 1986-87 acclaimed DC mini-series The Watchmen.

5 Lord Raglan’s monomyth and Mircea Eliade’s myth of the eternal return, not to mention

Joseph Campbell’s schema of the heroic cycle, easily apply to such heroes as Marvel’s 1941

Captain America by Joe Simon and Jack Kirby, or DC’s 1938 Superman by Jerry Siegel and Joe

Shuster.

6 As in Marvel’s 1963 The X-Men by Chris Claremont, noted for its ongoing allegory on

subjects such as racism (the 80s “Genosha” storyline), anti-Semitism (the first X-Men film), or

homophobia (the “Cassandra Nova” 2002 storyline and the second X-Men film).

7

Thierry Groensteen, “Why are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization?” Comics and

Culture: Analytical and Theoretical Approaches to Comics, Shirley Smolderen, trans., Anne

Magnussen and Hans-Christian Christiansen, eds. (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum P./U of

Copenhagen, 2000); 29-41. On the negative view of comics, see: Amy K Nyberg, “Poisoning

Children’s Culture: Comics and Their Critics,” Scorned Literature: Essays on the History and

Criticism of Popular Mass-Produced Fiction in America, Foreword by Madeleine B. Stern, Lydia C.

Schurman and Deidre Johnson, eds. (Westport, CT: Greenwood, 2002): 167-86.

8 Qtd. in: Roger Sabin, Adult Comics: An Introduction, New Accents series (London and New

York: Routledge, 1993): 98.

1

2

American pop mindset shows in the huge and ongoing success of the comics industry.

Because of its simplicity and use of fantasy, the comics image may be viewed as a

Jungian archetype, a vulgate myth-like (thus immediately communicable)

signification of a basic idea (e.g., heroism) sprung from the collective unconscious. At

the same time, as a conscious artistic effort, it reflects the cultural-political zeitgeist as

perceived within itself since, according to W. J. T. Mitchell: “It should be clear that

representation, even purely ‘aesthetic’ representation of fictional persons and events,

can never be completely divorced from political and ideological questions; one might

argue, in fact, that representation is precisely the point where these questions are most

likely to enter the literary work.”9 As Klaus Kaindl notes, comics are a genre “very

strongly governed by conventions,”10 and that furthermore, as regards their

“multimodal” nature:

[Umberto] Eco, (1972:202) for one, has demonstrated that pictures have a

code which is governed by conventions, and these conventions may be shaped

by cultural constraints. This also means that the visual representation of

objects, gestures, facial expressions, etc. can be interpreted correctly only if

the significance of these elements has been defined in the particular culture

(cf. Eco 1987:65).11

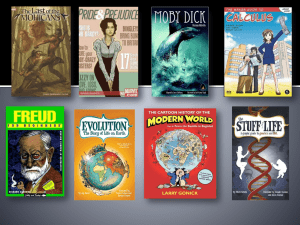

Comics run the gamut from teenage boys’ fantasies of ghastly quality (given

that “90 per-cent of mainstream readers are adolescent males ranging in age from

about twelve to twenty”—12 to thoughtful artistic masterpieces.13 The only thing all

comics seem to have in common is that their particular philosophy, or lack thereof, is

primarily conveyed through a specific code of bodily representation, as often the

illustrational background is immaterial (a tradition probably inherited from the blank

W.J.T. Mitchell, “Representation,” Critical Terms for Literary Study, Frank Lentricchia and

Thomas McLaughlin, eds. (Chicago and London: The U of Chicago P, 1999): 15. On the

subject of comics as reflections of culture, see: Joseph Witek, “From Genre to Medium:

Comics and Contemporary American Culture,” Rejuvenating the Humanities, Ray B. Brown

and Marshall Fishwick, eds. (Bowling Green, OH: Popular, 1992): 71-79; also: Thomas M.

Inge, Comics as Culture, (Jackson: UP of Mississippi, 1980).

10 Klaus Kaindl, “Multimodality in the Translation of Humour in Comics,” Perspectives on

Multimodality, Eija Ventola, Charles Cassidy and Martin Kaltenbacher, eds., Document Design

Companion 6 (Amsterdam and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2004): 183.

11 Kaindl 183.

12 Matthew Pustz, Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers (Jackson, NC: U of

Mississippi P, 1999): 13.

13 Examples of the latter are, among others, Astérix (a René Goscinny and Albert Uderzo hit

since 1959-61), Raw’s 1972 Maus by Art Spiegelman and DC’s 1989 The Sandman by Neil

Gaiman.

9

3

squares of early cartoon strips). Still, as Sigmund Freud opined, human truths lurk

especially in bad, “egocentric” art,14 while artistic quality, especially after the 1980s,

is no longer the sole privilege of alternative comics. Some mainstream comics that

have written history in the genre continue to evoke respectful interest even in present

age of savage competition. One of these is the 1961 book that actually “revolutionized

comics...and gave birth to what is now called the Marvel Universe,” creating the

phenomenon of Marvel Comics (today part of the colossal Marvel Entertainment

Group).15 It was the vehicle for the innovative art of two giants in the field:16

creator/author, comic-book icon and Marvel President, Stan Lee, and the man who

“quite simply...is American comics,” celebrated artist Jack Kirby—17and its title was

The Fantastic Four.18 The recent blockbuster film with the same title that premiered

July 8, 2005, as well as its 2007 sequel, have given rise to much talk about aspects of

the book and its adaptation, mostly among aficionados.19 What this essay intends to

show, however, is that the unique value and appeal of the FF lies in that its characters

were the first to present to their audience a new (mainly bodily) heroic form, one that

challenges

prescribed

forms

of

beauty

by

deconstructing

them

with

technoscientifically-generated hyperbole to the point of grotesqueness. Furthermore, it

wants to suggest that this new, mutated heroic model reflects the changing aesthetic

and cultural attitudes of U.S. teens then and now.

II. From the Classical to the Grotesque Heroic Body

The story of The Fantastic Four appears on a certain level artistically naive

and typical of comic books: four friends, attempting to be the first interstellar

Sigmund Freud, (1908) “Creative Writers and Daydreaming,” Critical Theory since Plato,

Revised ed., Hazard Adams, ed. (Fort Worth: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers,

1992): 714-15.

15 Mark Voger, “Living Legend: A Half-century Later, Jack Kirby Is Still the American Comic

Book,” Comics Scene Yearbook 2 (1993): 36.

16 Will Murray, “Farewell to the King: Friends Remember That King of Comics, the

Legendary Jack Kirby,” Comics Scene 42 (May 1994): 14.

17 Voger 36.

18 Stan Lee, writer, and Jack Kirby, penciller, The Fantastic Four (New York: Marvel

Comics/Marvel Entertainment Group, 1961). All Marvel characters examined in this article

are property of Marvel Comics/Marvel Entertainment Group and are used by license

graciously granted for academic purposes by their copyright owners.

19 The Fantastic Four, Tim Story, dir., starring Kerry Washington, Chris Evans, Jessica Alba,

Ioan Gruffudd, Michael Chiklis, Julian McMahon (Marvel Entertainment Group, 2005); The

Fantastic Four: Rise of the Silver Surfer, starring Chris Evans, Jessica Alba, Ioan Gruffudd,

Michael Chiklis, Julian McMahon, Lawrence Fishburne (Marvel Entertainment Group, 2007).

14

4

travellers on a private spaceship, encounter an accidental storm of cosmic rays and are

bodily transformed by the radiation into elemental super-powered beings. Vowing to

use their powers for good as a group called the Fantastic Four, they establish

themselves in New York and become American icons as well as protectors of the

nation, the planet, and the universe.20

The realization of the story has been marked unalterably by the 50s-60s

mentality of its creation time: the heroes wear demure full-body uniforms and their

attitudes and types reflect a conservative W.A.S.P.-ish set. The book clearly promotes

post-War era suburban values such as affluence and complacency, the space-race (as

the Marvel Encyclopedia notes, “The Fantastic Four are not super heroes in the

traditional sense.[....] They are astronauts, envoys, explorers...trailblazers”21),

vigilance against the Communist threat, and the Baby-Boom emphasis on family

values, as, “whatever dangers they face, they face as a family.” 22 However, a

particular infusion of the grotesque in the FF—whose mutated bodies are not the

perfect homo sapiens specimens that Superman’s or Captain American’s are—

combined with the usual comic-book conventions, oddly serves also as a questioning

and caricature of the above values, while engaging in the postmodern anxiety of the

human identity grounded on the body, and issues of species versus technology,

virtuality, and fictions of the self.23 After all, “the grotesque” is defined as:

decorative art in sculpture, painting, and architecture characterized by fantastic

representations of human and animal forms often combined into formal

distortions of the natural to the point of absurdity, ugliness, or caricature.... By

extension, grotesque is applied to anything having the qualities of grotesque

art: bizarre, incongruous, ugly, unnatural, fantastic, abnormal.24

Thus it stands to reason that the combination of human and superhuman, although

intended for appeal, may lead to that effect. This is also supported by Rosi Braidotti’s

discussion on monsters, “human beings who are born with congenital malformations

Matt Brady, Marvel Encyclopedia, Mark Beazley and Jeff Youngquist, eds. (New York:

Marvel Comics, 2002): 68.

21 Brady 68.

22 Brady 68.

23 A methodologically similar, yet admittedly much more negative critique of fantasy-asallegory of the pathology of culture can be seen in Louis Marin’s 1977 “Disneyland: A

Degenerate Utopia,” Contemporary Literary Criticism, 3rd ed., Robert Con Davis and Ronald

Schleifer, eds. (New York and London: Longman, 1994): 283-95.

24 Hugh C. Holman and William Harmon, "Grotesque," A Handbook to Literature, 6th ed. (New

York: Macmillan, 1992): 219.

20

5

of their bodily organism [....] defined in terms of excess, lack, or displacement of

organs,” evoking both fascination and abhorrence.25 In fact the malformed

superheroic may be a particularly American variant of grotesque, if we accept Jean

Baudrillard’s claim that the “American ‘way of life’” is characterized by:

its mythic banality, its dream quality, and its grandeur. That philosophy which

is immanent not only in technological development but also in the exceeding

of technology in its own excessive play...in the apocalyptic forms of

banality...in the hyperreality of that life which, as it is, displays all the

characteristics of fiction.26

In the FF in particular, comic grotesqueness furthermore can be seen as an attempt to

liberate the body from the tyranny of classical form concepts on which comic book

artists had been up to that point attached: the “Greek fold” on the pelvis, the

foreshortened limbs and the powerful upper torso of the 8th century BCE kouroi that is

duplicated in every Batman or Captain Marvel pose well until the 1990s. Given that

the origin of the group lies not in some mysterious magical or divine event, but in a

scientific experiment, the comic raises in the early 60s questions debunking both the

myth of the teleological race of the species to achieve the beautiful, that is, the

rationally-understood self, as well as the transcendental signified of the unalterable

“naturaleness” of the resulting human beings. After all, according to Arthur Kroker,

there is a more-than-symbolic connection between space-travel and the metahuman

(or posthuman) self: “Maybe we are already living in another dimension of space

travel: in a sub-space warp jump, a virtual reality where we can finally recognize that

we are destined to leave this planet because we have already exited this body.”27

Accordingly, one must amend the comic hero representational code as theorized by

Umberto Eco, who, in “The Myth of Superman,” speaks of a heroic-comic prolonged

destiny:

The mythological character of the comic strips finds himself in this singular

situation: he must be an archetype, the totality of certain collective aspirations,

and therefore he must necessarily become immobilized in an emblematic and

Rosi Braidotti, Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in Contemporary Feminist

Theory, Carolyn C. Heilbrun and Nancy K. Miller, eds., Gender and Culture series (New York:

Columbia UP, 1994): 7-8.

26 Jean Baudrillard, (1986) America, Chris Turner, trans. (London and New York: Verso, 1995):

95.

25

6

fixed nature which renders him easily recognizable...; but since he is marked

in the sphere of a “romantic” production for a public that consumes

“romances,” he must be subjected to a development which is typical...of

novelistic characters.28

The superhero, then, must “remain ‘inconsumable’ [i.e., fixed, because already

consumed and permanently altered by his heroic difference] and at the same time be

‘consumed’ according to the ways of everyday life” to keep the series going. 29 Eco,

however, oversees the dimension of heroic density in modern comics, where the

fusion of, and tension between, the subversive fantastic and the conforming mimetic

can create a bodily self that is multifaceted, playful, and “into” the metanarrative of its

artificiality. To put it in other words, archetypes are highly complex and compacted

items; allowing the possibility that their “romantic” narrative “unpacking” will lead

not to some heroic resolution, but to an open-ended exacerbation of their latent

bizarreness. Therefore we can speak of an ideal grotesqueness in the sense of a

hyperbolic (i.e., hyper-explored, extended) depiction of classical heroic beauty that,

clashing with altered notions of the body and what is human in the 20th century,

reflects a prevalent existential angst.

III. Mr Fantastic: Science Stretched Too Thin

An examination of the portraits of each of the FF members, with emphasis on

their fantastic bodies will serve to illustrate the above concept, demonstrating also

how the “multimodality” of the “hybrid genre” of comics, according to Kaindl, allows

the critical reader to operate both on the level of “linguistic elements” and that of

“pictographic elements” and “pictorial representations,” as well as via “intertextual

reference.”30 We should note first that the number four is in itself significant. It recalls

the holy number of cosmic order in several (folk) mythologies and Carl Gustav Jung’s

“four functions of consciousness, or the four stages of the anima or animus” that

create the mature, “individuated” self.31 Accordingly, each FF member will be shown

Arthur Kroker, SPASM: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh, Culture Texts Series

(Montréal: New World Perspectives, 1993): 38.

28 Eco, Umberto, “The Myth of Superman.” The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and

Contemporary Trends. 2nd ed., David H. Richter, ed. (Boston: Bedford, 1998): 867-68.

29 Eco 868-69.

30 Kaindl 173-74.

31 Marie L. von Franz, “The Process of Individuation,” Man and His Symbols, Introduction by

Carl G. Jung, ed. (New York: Dell/Laurel, 1968): 214.

27

7

to embody an aspect of the Jungian psychosomatic tangents that synthesize the

holistic self: that is, the Self, the ego, the animus and the anima.

Reed Richards, codenamed Mr. Fantastic, the unquestionable leader of the

group, is prototype of the American man of the 50s-60s. The “consumed” hero in

Eco’s theory32 can be seen as an apt metaphor of the American self, which for

Baudrillard, “Having known no primitive accumulation of time, it lives in a perpetual

present”—something that would explain the everyday fabulism of American life.33

Reed, accordingly, is already “consumed” as a multimillionaire scientific genius who

creates an interstellar rocket, so his role changes little when his entire body acquires

the ability to stretch like sentient rubber. Mr. Fantastic represents fittingly the Self, or

the overall controlling “mind” of Jung’s fourfold division. As Marie von Franz says:

The organizing center from which the regulatory effect stems seems to

be a sort of “nuclear atom” in our psychic system. One could also call it the

inventor, organizer, and source of dream images. Jung called this center the

“Self” and described it as the totality of the whole psyche, in order to

distinguish it from the “ego,” which constitutes only a small part of the total

psyche.34

In fact, stretching serves as a physical metaphor for American identity since, as

Stephen Fender shows, the immigrants’ journey across the Atlantic and the creation of

the a new national super-imposed identity is a staple of the “American Difference,”

and “exceptionalism.”35 It also stands, however, for American techno-scientific

theories and capacity (a point also made ironically at the beginning of the film). In

this “dreamer’s” stretching are summed the 50s miracle of atomic energy and the 60s

space program optimism about reaching the stars,36 democratically available to all

adventurers, as shown by Marvel’s and “the world’s first ‘imaginauts’”;37 the

expanded limits of knowledge; the blanketing hegemony of reasonable theory which

Reed continuously spouts; the extension of the self through bulky exo-skeletonic

Eco 868.

Baudrillard 76.

34 von Franz 161-62.

35 Stephen Fender, “The American Difference," Modern American Culture: An Introduction,

Mick Gidley, ed. (New York: Longman, 1994): 7-8.

36 Preoccupation with the space-race program, as seen poignantly in Oriana Fallaci’s

journalistic memoir-novel of post-War America, If the Sun Dies (New York: Kingsport, 1966),

had reached the point of national craze among all age groups, and led then to scientific

speculations that appeared much more fantastic than even comic book scenarios.

37 Brady 68.

32

33

8

machines, such as Reed ceaselessly constructs in his lab, and which signal not only

the infantile wish of the brain for rapid maturation of the “premature” body, 38 but also

clearly a penile valorization, where expansion matters. In Jungian terms too, the

controlling-synthesizing principle that Reed Richards represents is often pictured as

the archetype of the “Cosmic Man”: “a gigantic, symbolic human being who

embraces and contains the whole cosmos” and appears in someone’s dreams to herald

a “creative solution to his conflict.”39 Mr. Fantastic fights by wrapping tight around

his foes (or angry friends, in the film) like a giant straightjacket (symbolically

restraining demented evil or rage by good reason). In short, his body is literally the

cliché of the word made flesh—and a phallogocentric cliché at that (as Reed is always

right—in theory!).

Mr. Fantastic is furthermore cast as the group paterfamilias, designating his

sobriquet as a generic name to his “Fantastic” clan. He also has this dignified older

look, always neat and shaven, with a reed-y body, graying temples, and, until the 80s,

a pipe. Reed is duty-obsessed (rarely eats or plays) and painfully sober—the epitome

of the dysfunctional scientist. This nerd quality is exaggerated in the first film to the

point of making him appear constantly victimized: Reed is called “the world’s

dumbest smart guy” by fellow member Torch and the first manifestation of his

stretching powers is characterized as being “gross,” while later he is rubberized to the

point of literally losing bodily coherence and “melting.” In other words, he looks

nothing like the typical twentysomething superhero, with the buff, solid body and the

“gung-ho” attitude, reflecting perhaps an early sign from the turn from the hegemony

of the “quarterback” macho masculine model to that of the 21st century

“metrosexual.” Reed is furthermore responsible to a fault—literally, for the spaceship

fiasco of the group’s genesis. While the typical (super)hero only reacts to the trauma

of some personal or general injustice, Reed is the sole author of his own trauma, and

those of his team-mates (something only seen in recent pop heroic figures, such as

Xena: Warrior Princess). Like the veterans that lived through the trauma of a World

conflict and must exonerate for, and be vigilant about, history, Reed battles foes

allegorical of the World War (read: cosmic ray assault), the Red Scare (as in the FF’s

antithesis, the Soviet team of the Frightful Four), and the H-Bomb (a cosmic

Jacques Lacan, (1949) "The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as Revealed in

Psychoanalytic Experience,” Contemporary Literary Criticism, 3rd ed., Robert Con Davis and

Ronald Schleifer, eds. (New York and London: Longman, 1994): 384.

38

9

Destroyer known as Galactus, the villain of the second film) in order to bring about

this new age of prosperity, progress and family values. This hope that all can heal is

known as “comic-book physics,” where freak accidents don’t kill, but grant superpowers, and even an atom bomb explosion can eventually lead to good.40

Nevertheless, the cool dependability of Mr. Fantastic comes at the cost of his own

paranoia, resembling his body that can super-stretch, but in the stretching loses its

human shape and structure, becomes amorphous—and can constrict one to death in

trying to offer a protective techno-enhanced hug. The superphallic quality of Reed’s

body is also mocked by a feminizing penetrability of his faculties: he isolates himself

in his lab experiments, only to be usually the one to detect or create thus the FF’s

newest threat. His technologically-advanced Manhattan skyscraper, which serves as

the FF headquarters and is named “Four Freedoms Plaza”—suggesting the fourfold

basis of the American Dream—is continuously broken into by supervillains, while his

dreamed-of life is always threatened. And all that because his hubristic spaceship was

penetrated by cosmic rays,41 when Mother Nature decided to show the Male Scientific

nous who’s boss by afflicting the male body with a feminized pliancy and softness—

and making him like it, too!

Finally, although Reed is the one to whom all the other teammates relate

immediately, he bungles his social duties, prefering his laboratory sanctum: no matter

how much he can stretch, the brain’s self-referentiality is a limited state of being.

Ironically, Reed’s oldest relation is to the arch-enemy of the FF, the evil genius

Victor Von Doom, or Dr. Doom. Typically the alter Ego of the scientist, Doom stands

for the dark monstrous Other to the mythical hero, with a name that recalls mad

professors like Dr. Strangelove,42 or even J. Robert Oppenheimer.43 Although Dr.

von Franz 211.

An issue most thoroughly and controversially explored in Marvel’s 1962 The Incredible Hulk,

again by Stan Lee and Jack Kirby—whose two film adaptations have joined 2008’s Iron Man,

the three X-Men, and three Spiderman films (so far) as a Marvel screen blockbuster.

41 In the film, in fact, the hubris is lessened by having the space station (this time) belong to

Reed's antagonistic former classmate who now funds Reed’s ambitious project, Victor von

Doom (see more below). While Reed only wants to study the cosmic ray storm for medical

purposes beneficial to humankind, von Doom’s faulty equipment, so to speak, and his

insistence that the experiment go on, despite the danger, are what bring about the

transformation. The change, though serving well the “Good Scientist, Bad Tycoon” motif,

blunts the intricacy and sharpness of the questions posed by the original comic, on whose

thinking this paper is based.

42 The character, a caricature of Henry Kissinger that became a cultural metaphor, comes from

the 1964 offbeat film hit by Stanley Kubrick (who also wrote the screenplay with Terry

39

40

10

Doom’s status from orphaned nomad to monarch of Latveria (a fantastic Balkan

nation)44 contrasts to the democratic, family-oriented U.S. and its 60s fear of Eastern

Communism, the Latverian prosperity suggests a kind of paternalistic enlightened rule

not unlike Reed’s own leadership of his team. Doom was Richards’s college peer and

rival, and it was due to their frenzied competition that Doom conducted an erroneous

experiment that resulted in his disfigurement and subsequent permanent encasement

in full body armor, topped by a medieval (i.e., anti-New World) green cowl and

cape.45 Antithetical to Reed’s stretching, Doom’s containing armor is, nevertheless,

also a technologically-advanced device like a cosmonaut suit, signifying the dark side

of Reed’s self-isolating vision which, for Groensteen, is duplicated by the “‘existential

dream’ that a reader experiences when he plunges into the world of small pictures.”46

After all, for Kroker:

Heidegger was wrong. Technology is not something restless, dynamic and

ever expanding, but just the opposite. The will to technology equals the will to

virtuality. And the will to virtuality is about the recline of western civilization:

a great shutting-down of experience, with a veneer of technological dynamism

over an inner reality of inertia, exhaustion, and disappearances....47

Right from the start, therefore, the comic book questions the purity of its superheroic

model and simultaneously casts a shadow (em-bodied as well as reflected in the

Lacanian mirror-image of “dark-Ages” Doom) over the American obsession with the

Southern), starring Peter Sellers, Dr. Strangelove, Or: How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love

the Bomb.

43 In what has become by now an anecdotal piece of Americana, Oppenheimer, seeing his

plutonium bomb explode at Los Alamos on July 16, 1945, finally realized the ramifications of

his team’s creation and whispered the line from the Hindu epic of the Baghavad Gita: “Behold,

I am become Death, the Shatterer of Worlds.” See: Mark C. Carnes, “About J. Robert

Oppenheimer,” American National Biography (New York: Oxford UP, 1999), May 12, 2003,

Online,

Internet,

available

WWW:

http://www.english.uiuc.edu/maps/poets/af/aboutopp.htm .

44 Brady 87.

45 Echoing Alexander Dumas’s 1846 The Man in the Iron Mask--and acknowledgedly

foreshadowing Darth Vader, according to: Donald D. Markstein, “The Fantastic Four,”

Toonopedia,

May

12,

2003,

Online,

Internet,

available

WWW:

http://www.toonopedia.com/fant4.htm. In the film, Doom’s similarity to Reed and the rest

of the group is in fact heightened by having him also be exposed to the cosmic rays and

mutate into an organic metal being with electromagnetic powers. The difference there is that

while Reed views the mutation as “an infection,” Doom enjoys it as a step towards

godhood—reflecting the typical division between humanitarian (usually medicine-related)

aspects of science and industrial technology that corrupts one’s humanity out of them and

turns them into “robots.”

46 Groensteen 40-41.

11

improvement of the body through technoscience (particularly intensified today with

cyborg mechanics and genetic alchemy).

IV. The Invisible=Woman: A Storm and Her Teacup

The early-60s mark of the FF comic is equally evident in Reed’s fiancée and

later wife, Susan Storm-Richards, a.k.a. The Invisible Girl (subsequently, the Invisible

Woman). It is no wonder, therefore, that of all the characters she was the one most

revamped in the 2005 film, played by the best-known actress among those involved,

and upgraded to a fellow top scientist and a prize of contention between Reed and von

Doom. The name alone suggests the textbook case of woman in patriarchy, as

“‘Woman’ is that which is assigned and has no power of self-definition.”48 The

Invisible=Woman is the blank (i.e., penis-less) spot, as “unrepresentable” as death on

which, according to a slew of feminist critics, the phallogocentric empire of the

symbolic sign is inscribed and built.49 Her role as “impressionable” tabula

permanently rasa is heightened by the age-difference between her and Reed: she was

12-year old when she developed a crush on Reed as a graduate student, so in a sense

she is also “consumed” before she is erased.50 Sue is typically “ladylike,” blonde (a

hue next to invisible), and usually penciled as Doris Day or June Cleaver—51 that is,

an “invisible” original self styled as a copy of the ideal 60s housewife. Most

ironically, the sacrifice of her aspirations to movie stardom in order to serve invisibly

her “family”’s greater good,52 and her subsequent high-visibility as team lady only

reinforces the schema of a woman’s erasure-and-reinscription according to the

patriarchal codes of representation. Sue’s auxiliary power to produce invisible forcefields that can briefly envelop and shield the others from trouble makes her the bodily

metonymy for the sheltering home which is a woman’s oyster. Her modus operandi is

Kroker 7-8.

Braidotti 63.

49 Hélène Cixous, “The Laugh of the Medusa,” Feminisms: An Anthology of Literary Theory and

Criticism, Robyn R. Warhol and Diane Price Herndl, eds. (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP,

1991): 342.

50 Brady 73.

51 Television’s W.A.S.P. situational comedy idols of the 50s and the 60s, looking practically

identical in their short platinum-blonde coiffs, blue eyes, matching pastel outfits and

perennially sunny, angel-in-the-house disposition, these actresses/typecast TV characters (the

former the star of several films and shows, and the latter the “mother” in the series Leave It to

Beaver) created a slew of female imitators on- and off-screen, cementing the legend of the

impeccable American suburban housewife.

52 Brady 73.

47

48

12

to sneak undetected in or, usually, out of the battlefield, fall unconscious or captive

(due to a soft heart and unsound judgment), and then get rescued by the male

members of the FF, worrying all the while whether Reed (who usually ignores her

pleas, thus making her twice invisible)53 has had his dinner, even when the world is

literally coming to an end!54

Sue’s utter devotion and deference to Reed appears to earn her the position of

the anima in the Jungian quadripartite division of the personality, that is, “the female

element in every male,” especially since Jung describes the anima as essentially a

certain inferior kind of relatedness to the surroundings…which is kept carefully

concealed from others as well as from oneself.”55 In addition, “the anima appears in

her proper positive role…as a mediator between the ego and the Self,” 56 a role which

Sue fills by always easing the tension between Reed-the Self and her flamboyant

brother, the Torch, whom we shall see occupies the ego position. Ostensibly the

motivator and “heart” of the team body,57 the Invisible Sue nevertheless also serves

the model of the tainted “Eve” of phallogocentric mythos, by developing an attraction

for another former foe—later superhero—Namor the Submariner, the amphibian

Prince of Atlantis, and thus stands accused of betrayal by her teammates.58 This

excess of primal female desire uncontained by domesticity or Reed’s “stretching” is

the chink in the armor of optimistic technology that characterizes the FF, their antiLacanian “lack” that she makes visible. In another sense, Sue is a domesticated

manifestation of the Medusa archetype, the anxiety-inducing symbol of the

“castrated” female genitals—59 and it is no coincidence that her invisibility is always

depicted as a fading from the waist down.60 Further ironic is the fact that, by necessity

Bowing to the changed mores of the 21st century, this trait is turned to Sue's advantage in

the film, where Reed admits that his ignoring of Sue's (and his own) needs and amorous

feelings was what led to their earlier college breakup and subsequent estrangement.

54 As literally depicted in Stan Lee, writer, and Jack Kirby, penciller, “The Coming of

Galactus!” The Fabulous Fantastic Four: Marvel Treasury Edition 1.2 (December 1974): 59.

55 Carl Gustav Jung, “Approaching the Unconscious,” Man and His Symbols, Introduction by

Carl G. Jung, ed. (New York: Dell/Laurel, 1968): 17.

56 von Franz 195.

57 Brady 73.

58 Stan Lee, writer, and Jack Kirby, penciller, “Captives of the Deadly Duo,” The Fabulous

Fantastic Four: Marvel Treasury Edition 1.2 (December 1974): 15.

59 David Hillman and Carla Mazzio, The Body in Parts: Fantasies of Corporeality in Early Modern

Europe (New York and London: Routledge, 1997): xvi; also Cixous 342.

60 On the discussion of woman as monster, see also Braidotti, esp. 79-83; and Kristevan film

theorist Barbara Creed’s book The Monstrous Feminine: Film, Feminism and Psychoanalysis

(London: Routledge, 1993).

53

13

of comic-book semiotics, where everything must be imaged, the Invisible Woman is

never truly invisible! Usually shown as/in a white cutout, or as a dotted-line sketch (a

universal signifier, ironically, for “object missing”), she remains prey to the

patriarchal division of “woman as image, man as bearer of the look,”61 but

simultaneously invites the reader to reconstruct the missing lady by paying enough

attention to her. She is the spectre that haunts observable (ergo, scientific)

epistemology. This suggestion might also be aided by the fact that comics are

considered a “feminine” genre, not only because the image is considered as the

sensory/”seductive” counterpart to masculine logos/text, but additionally because

comics subject respectably macho males to gaudy, even garish costumes.62 The

Invisible Woman’s later 1994 “liberation”—albeit brief—from her demure 60s fullbody costume (with a midriff-less swimsuit featuring a cutout “4” right on her

cleavage) may on the one hand obviously serve to titillate the teen male audience, but

on the other provides her with enough provocative “naughtiness” to gain central

focus: to use Cixous tongue-in-cheek, “women are body. More body, hence more

writing.”63 What in fact the play between in/visible and femininity in the case of

Susan Storm-Richards makes apparent is how, in its commercially- and culturallydriven quest for beautiful visibility (of which Sue is a model, literally), the authentic

image of each woman always suffers, and can be easily erased. What, one wonders, is

worse, being prettily normal, i.e. invisible, or being noticed as ugly? In the film the

monstrous Thing votes first for the former option, but ends up triumphantly trading it

for helpful—i.e, visible—ugliness in the end. Finally, Sue does credit to her surname,

Storm, by providing the unsettling natural force which—like the cosmic ray storm—

upsets the road to a scientific utopia. For Braidotti, the “monstrous” female body has

been the venue of inscription, “progressing from the fantastic dimension of the bodily

organism to a more rationalistic construction of the body-machine,” and

simultaneously of negation of patriarchal scientific thought.64 In the same way, in the

FF Sue produces two children with chaotic potential: her son Franklin, a superLaura Mulvey, (1975) “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema,” Contemporary Literary

Criticism, 3rd ed., Robert Con Davis and Ronald Schleifer, eds. (New York and London:

Longman, 1994): 425.

62 For the gendered division of image and word, as well as the impact of technology on those

concepts, see: Mary E. Hocks and Michelle R. Kendrick, eds., Eloquent Images: Word and Image

in the Age of New Media (Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2003).

63 Cixous 343.

64 Braidotti 83.

61

14

powerful mutant due to his inherited genetics, is set to become in the future either the

Savior, or the Destroyer of Worlds, verifying on the one hand the myth of woman as

Madonna/Eve, but on the other affirming female (pro)creativity over male technocreation. Her daughter Valeria, in addition, owes her safe birth to Dr. Doom, who

steps in when Reed is unable to help. Susan then lets Doom become the godfather and

guardian of her daughter, leading by a regression to an organic and purely bodily path

toward a reconciliation of magic and science, medievalism and futurism, evil and

good that Mr. Fantastic’s technology, with all its attempts to render woman invisible

and supplant her powers with machines, could not achieve.65

V. The Human Torch: No Man on Fire

That leaves Susan’s younger brother Johnny Storm, a.k.a. the Human Torch,

as the epitome of superheroic bodily parody. Granted by the cosmic rays the power to

light up his whole body in living fire, project flames, and fly, the Torch takes his

former hobby of hotrod car racing to turning his own body into that high-technology

hotrod.66 The obvious representation of not only the torch of Liberty, an American

symbol, but also an idealized Baby-Boomer generation—fast, shining, high-flying,

ever-youthful, good-looking—is overshadowed however by the inability of Johnny to

ever slow down or evolve beyond his shallow sophomoric self. He represents the team

spirit; but the spirit of America’s biotechnological future is ever-racing, and to reign it

in by way of a maturation process that would make the Torch less hot but more

Human mocks the potential for everlasting dynamism that is America. For, “in

America,” Baudrillard observes, “the arrival of night-time or periods of rest cannot be

accepted, nor can the Americans bear to see the technological process halted”—as

seen symbolically in “the obsessive fear of the Americans...that the lights might go

out.”67 In Jungian terms, the Torch represents the ego, the part of the personality that

tends “to follow its own arbitrary impulses” but only so as “to make real the totality—

the whole psyche. It is the ego that serves to light up the entire system, allowing it to

become conscious and thus to be realized” (emphasis mine).68 It is indeed very often

the Torch’s impetuous and reckless actions that mobilize the team to a new adventure,

or start some drama, but only as far as he follows Reed’s leadership to a happy

Brady 88.

Brady 71.

67 Baudrillard 50.

65

66

15

conclusion. In the same way, the ego is said to be productive only when it is “able to

listen attentively and to give itself, without any further design or purpose, to that inner

urge toward growth,”69 a trait stressed in the film too, where Johnny is the first to

embrace, name, and initiate the superhero team identity, but is only useful to it when

he subdues his blatant egoistic immaturity. Since comics require constant action,

however, those spells of human sobriety are soon burnt out, and it has been an

increasing staple of the comic-book to show the Torch “incapable of committing to a

serious, long-term romantic relationship.... Immature and prone to distraction in other

areas.[....] Impetuous and hotheaded.”70 Johnny Storm is further undermined by the

fact that he is not the original Human Torch, but a re-creation of a 40s “Golden Age”

android superhero by the same name. This “passing on the torch” offers Johnny some

legitimacy, but also sets an unsettling comparison between this technologicallymutated human who loses his humanity and the older, more dignified robot that

achieves humanity and heroism by painstaking effort. Johnny’s plight suggests then

that mere bodily evolution without the comparable mental or spiritual ripening leaves

paradoxically one a mere “spirit” indeed—like alcohol, very flammable, but with no

underlying substance.

VI. The Thing: Grotesque Rocks!

Representing the body in the fourfold division of the self, Benjamin Grimm,

a.k.a. “the Thing,” is finally the only member of the team with a nonhuman

codename, not kin to the others, wearing merely a pair of briefs (or, later, tights)

instead of a bodysuit, and so is in every way distanced from the other three. While the

others represent the “giant step” forward, he is like a primeval stone-idol drawn from

the archetypal unconscious (though such idols carried an unusual amount of

animation).71 According to von Franz, “the stone symbolizes what is perhaps the

simplest and deepest experience—the experience of something eternal that man can

have in those moments when he feels immortal and unalterable.”72 Since the cosmic

von Franz 163.

von Franz 164.

70 Brady 71.

71 Aniela Jaffé, “Symbolism in the Visual Arts,” Man and His Symbols, Introduction by Carl G.

Jung, ed. (New York: Dell/Laurel, 1968): 259.

72 von Franz 224. As Baudrillard also says about America, “It is metamorphic forms that are

magical. Not the sylvan, vetrified, mineralized forest.{..} It takes this surreality of the elements

to eliminate nature’s picturesque qualities, just as it takes the metaphysics of sped to

68

69

16

rays turn his skin into a hideous orange rock-like growth, trapping him into a superstrong and invulnerable shell, the Thing in one sense resembles more Dr. Doom than

the other team members, who can invoke their beautiful human bodies anytime. Yet

Ben comes across unquestionably (both in the comic book and the film) as the most

human of the FF, perhaps, for one, because, as Jungians say, stones “are especially

apt symbols of the Self because of the ‘just-so-ness’ of their nature”73 that eschews

any alienating super-imposition. For another reason, Ben’s role is the one

comfortingly closest to the average man on the street, as opposed to a genius, a model/

wife, or a pop idol. His name evokes the Franklinean ethic that is the legendary

bedrock of the American marvel, since Ben chanced as Reed’s college room-mate

because of his football star scholarship, became a World War II combat hero, and

used his aviator talents to build his own successful enterprise. Thus Ben serves as the

Jungian animus, the inner masculine principle, both in its earliest manifestation as “a

personification of mere physical power—for instance, as an athletic champion or

‘muscle man’,” and in its more mature subsequent role as a source of creative

“spiritual firmness.”74 But Reed’s insistence that Ben pilot his experimental spaceship

tragically confines Ben into being the mere strongman of the team, exaggerating his

rough Hell’s Kitchen talk and attitude, summarized in the Thing’s battle cry: “It’s

clobberin’ time!”

A deeper still insight about technoscience is therefore intimated here, beyond

the obvious Shelleyan point that careless use of biotechnology can afflict one’s

dearest buddy with Frankensteinitis gravis. Techno-evolution, we are told, can

actually regress the human body, since by transferring skill, dexterity and importance

to the biomechanical aids, the original flesh loses its usefulness, becomes a hulking,

ungainly thing in contrast to its sleek and superfast accoutrements, and might as well

be a Stone Age throwback—a grim fate indeed, as Ben’s surname suggests. In Eco’s

terms, the Thing is the only hero who is really consumed by the accident; yet

ironically, by virtue of his afflicted body, Ben’s tragedy can also provide a reliable

point of contrast and criticism to Mr. Fantastic’s project. In fact, Ben is the only one

with his own philosophy and license to contradict, or make fun of “Stretcho.”

eliminate the natural picturesqueness of travel” (8-9). Therefore the presence of a stone man

draws attention both in primal and futuristic terms.

73 von Franz 221.

74 von Franz 206-07.

17

The Thing is also the only team member to constantly develop outside

relationships, something which designates him as the comic connection to the real

world: Ben Grimm represents the average male teenage comics reader, with his yetrough thinking trying to adjust to a changing, uncomfortable body that sprouts hair

and acne and a gravely voice, and with his attempt to mask the fear of change

underneath an armor of culturally-encrusted manhood and peer affections. In the

avant-garde way of the FF, he may also be an early sign of the fitness craze that has

been a basic trait of western society since the 1980s, and which has led thousands of

people, and especially insecure teens searching for strength and confidence, to “pump

up” their bodies, often monstrously, in gyms and through drugs, often illegal and

dangerous ones. To put it otherwise in Kristevan terms, the Thing is the symbolic

shell of patriarchal masculinity that congeals over the semiotic potential underneath—

and the irreversibility of the process, despite Reed’s frequent attempts to “cure” Ben,

suggests the gradual conditioning of humans to fit their assigned bodies. This speaks

for “Lacan’s description [in his 1953 “Some Reflections on the Ego”] of the formation

of subjectivity in the mirror stage, in which a sense of ‘primordial Discord’ emerges

alongside an image of corporeal totality, creating a fantasy of ‘the body in bits and

pieces’ as a retrospective representation of presymbolic chaos”—75 as pictured

eloquently in the fragmented, cobblestone quality of the Thing’s hide.

It is also through Ben that the comic book tilts this Platonic supertechnological

teleology towards the grotesque by going where Mary Shelley’s 1818 Frankenstein

feared to tread, i.e. in the realm of the sexuality of the monstrous body. As we learn

from Anne K. Mellor’s study, what drives Dr. Frankenstein to destroy his female

animant while still at the creation stage76 is fear of:

...female sexuality as such. A woman who is sexually liberated, free to choose

her own life, her own sexual partner (by force, if necessary). And to propagate

at will can appear only monstrously ugly to Victor Frankenstein, for she defies

that sexist aesthetic that insists that women be small, delicate, modest, passive,

and sexually pleasing—but available only to their lawful husbands.77

Hillman and Mazzio xvi.

Mary Shelley, (1818) Frankenstein, Or, The Modern Prometheus, Introduction by Diane

Johnson, Bantam Classics (New York and Toronto: Bantam, 1981): 150-51.

77 Anne K. Mellor, “Possessing Nature: The Female in Frankenstein,” Romanticism and

Feminism, Anne K. Mellor, ed. (Bloomington and Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1988): 224.

75

76

18

Such a lady appears in 1989, when fellow superheroine Ms. Marvel is accidentally

turned into a female Thing-clone with long eyelashes and breasts and becomes Ben’s

lover. On the one hand, “Ms. Thing” may be a simplistic male conceptualization of

the new 80s assertive woman: one of those Kirby women who, in Voger’s opinion,

“are beautiful in their own way, but they’re powerful and not altogether sexual.”78 The

romance promotes the comic-book soap-opera without transgressing into the

forbidden “contamination” of interspecies/interracial relationships (especially in a

comic-book without a single minority character in it!), and it is never concluded, as

the grotesque Ms. Marvel eventually reverts to pretty Sharon Ventura. Nevertheless, it

is sobering to consider, even briefly, the proliferation of the truly mutated body, the

nonhuman new human race, which might well be the projected foreboding on the

outcome of current cultural and technological tampering with the body.79 In the other

team-members, the reversal into a human bodily form offers the comfort of the

repeated and familiar sign whose recurrence in writing (here drawing), as Derrida

suggests in Of Grammatology, is the basis for a system of meaning;80 but in a world

of Things, what (signifying) value would the body have?

Adjacent to this issue is the deconstruction of the ostensible glorification of

team heroism, science and family values in the FF by the focus on the unpredictable

mutagenic potential of these same values. Alone, the body remains static; it is in its

relation to other bodies that transformation occurs. Although technology can interfere

with, or duplicate partly the process of adaptive mutation, the network of stimuli is so

much larger than a laboratory can hold, or predict. One is then led to wonder if it is

the infamous “bioapparatus” that we truly have to fear,81 or whether we should instead

focus on the transformations happening every day on a non-superheroic level due to

simple interaction. As Elizabeth Grosz writes, “human bodies have the wonderful

ability, while striving for integration and cohesion, organic and psychic wholeness, to

also provide for and indeed produce fragmentations, fracturings, dislocations that

Voger 38.

On the subject of the new conceptualization of the body in technoculture, see: Ollivier

Dyens, Metal and Flesh; The Evolution of Man: Technology Takes Over, Evan J. Bibbee and

Ollivier Dyens, trans. (Cambridge, MA, and London: The MIT Press, 2001).

80 Jacques Derrida, (1967) Of Grammatology, Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak, trans. (Baltimore:

The Johns Hopkins UP, 1976).

81 Kroker 162.

78

79

19

orient bodies and body parts toward other bodies and body parts.”82 Hence, one

should amend Eco’s observation that the superhero never changes, because s/he never

interacts with “our” reality on anything but a limited “civic” level. 83 The

informational density of the panels on the comic-book page, increasingly less linear in

its unfolding, where the body appears as both human and, in the same sweep of

vision, mutated; the further blending of such action images with word-balloons that

require momentary stasis; and the—often drastic—changes wrought on comic book

heroes by the changing of a penciller, or the re-casting of their origin in a new series

to reflect new mores or fashion trends, all these suggest the potentially transformative

complexity not only of the “su(pe)r-real,” but of the alluded-to real as well. At the

same time, this “constellation of script and image in their material difference, being

juxtaposed and integrated at the same time....parodies precisely that claim for a truth

beyond the signs, and directs our attention to the constellation of signs itself”—84 but

isn’t reality perception precisely such a sign system? Fantasy and reality interact

further as the artists habitually put a bit of themselves into their characters: Kirby

admits that many of his characters resemble him facially,85 while in the 2005 FF film

Stan Lee upholds a private film tradition and makes a cameo appearance as the

character Willie the Postman, who in the book brings to the team members fan mail

from their comic book readers! Adding to that mimetic realism on the page (especially

lately, with computer-assisted artwork), to superhero costumes at Halloween, to cooption of comic-book metaphors into the cliché stockhouse of language and culture,

we see comic escapism constantly returning back to its human source.

VII. Conclusion: A New Bodily Aesthetics?

Still, if the cluster of panels on the page or the relationship of the team

members in the FF is a bit like Foucault’s social web of “power/knowledge”

relations,86 then it must be admitted that there is no way out of that text;87 that “the

Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana

University Press, 1994): 13.

83 Eco 876.

84 Ole Frahm, “Weird Signs. Comics as Means of Parody,” Michael Hein, trans., Comics and

Culture: Analytical and Theoretical Approaches to Comics (Copenhagen: Museum Tusculanum

P./U of Copenhagen, 2000): 180.

85 Voger 36.

86 As seen in all of Michel Foucault’s work, but especially in his Discipline and Punish: The Birth

of Prison (1975) and Power/Knowledge (1980).

82

20

constellation of typographical and graphical signs....in their heterogeneous

materiality...are already self-referential,”88 or, as Thomas Beebee puts it, the “noise,”

“the non-systemic is simultaneously inside and outside the system.”89 The

“stretching” of the techno-evolutionary vision into the American future is, therefore,

either a chimera, or a metaphor for something else realizable within non-superhuman

parameters. By deconstructing from the inside the tensions inherent in the classical

ideal of the human form—which, if we remember its originating ideology, is itself

based not on the “human measure” of some normalcy but in the effort to transcend the

human and to become (running the risk of hubris all the while) isotheos, equal to the

gods—affirming the “play” of signification,90 the comic-book artist doesn’t simply

deliver a new and improved heroic body model, but also an escape from it. To the

extent, in fact, that comic-book drawing is a kind of caricaturing or parody,91 a

necessary abstraction in representation, this escape is already there—and justifiably

so. The metaphysical aim of physical grotesqueness is inherent, according to Kroker,

within the concept of high-technology or bio-technology utopianist visions:

...just like P.T. Barnum strained through the technological imperative: a

perfect fusion of the traveling carnival show and high technology. With this

difference:... a perfect crystallization of technocracy’s loathing of nature and

human nature [....] That’s the escape theme that pervades the promotional

language...: escaping from earth, escaping from the body, escaping from

America.92

The imperative for physical beauty, the cult of becoming the body has recognizably

become a hysteric concern for Western societies: “This omnipresent cult of the body

is extraordinary. It is the only object on which everyone is made to concentrate, not as

a source of pleasure, but as an object of frantic concern.…”93 Faced with the

impossibility of ever matching screen idols or supermodels, the vulnerable teenager

As is also shown by the whole Derridean endeavor, seminally in his 1967 De la

grammatologie, where there is nothing which is beyond the text and all one can observe is the

“traces” in the text of anomalies, philosophical tensions and the “plurivocity” of writing”

88 Frahm 180.

89 Thomas O. Beebee, The Ideology of Genre: A Comparative Study of Generic Instability

(University Park: Penn State UP, 1994): 17.

90 Jacques Derrida, “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences,”

Writing and Difference, Introduction and Additional Notes by Alan Bass, trans. (Chicago: The

U. of Chicago P., 1978): 292.

91 Frahm 179.

92 Kroker 17.

87

21

escapes into a fantasy world where this is realizable. On a deeper level, though, the

obfuscation or distortion of the classical heroic form in some mainstream (and most

alternative) comics, the stretching, pumping, twisting, mutating of the body is also an

attempt to inscribe a new set of aesthetic codes for what is desirable, or “super,” one

that liberates us (as seen from fan confessions in Pustz)94 from the tyranny of

prescribed form. It is no coincidence that, with the passage of time and the

exacerbation of youth existential anxieties, superheroes have been cast in ever scarier,

grotesque, traumatized molds, as evident in the comparison of the bodies of the FF in

the 60s with that of the most popular X-Man since the 1980s, the Hobbesian—short,

ugly, hairy and brutish—Wolverine. The FF themselves have also long been replaced

as the flagship of Marvel by the more daring X-Men, the true “homo superior”

mutants divorced from humankind as a species and as “uncanny” bodies (a trait

especially stressed in the teenage mutant characters among them).

In other words, if anorexic air-brushed advertoids are recognizably one form

of constructed fiction, setting standards more and more impossible to follow for the

average person, why not construct and promote an antagonistic one, that reflects the

stress (/stretch?) of perfecting the body? Even better, why not create a form that

transcends the body problem, or at least agonizes over the inability to transcend—the

“freak triumphant,” in Kroker’s words, “not...as a symbol of transgression, but of the

impossibility of transgression”?95 The Romantic (classical, actually) equation “Beauty

is truth” and vice versa is now replaced by Foucault’s more sober realization that truth

(and ergo beauty) “is a thing of this world…produced only by virtue of multiple forms

of constraint. And it induces regular effects of power.”96 If, therefore, the “regime of

truth” is dependent on power, in a world of super-powered beings it is this might that

sets the rules for what is desirable, exacting a small form of revenge, on behalf of

comic book readers (stereotyped as dysfunctional freaks) against what reality

aesthetics dictate. Perhaps we are returning to an age-old staple of heroic myth, as

identified by Northrop Frye, which operates “near or at the conceivable limits of

human desire,” but a desire, nevertheless, non-attainable by even the hero, who must

Baudrillard 35.

Pustz 83.

95 Kroker 127.

96 Michel Foucault, “From Truth and Power,” Colin Gordon, trans., The Norton Anthology of

Theory and Criticism, Vincent B. Leitch, ed. (New York and London: Norton, 2001): 1668.

93

94

22

suffer—often via metamorphosis—for attempting to transgress those limits.97 As

Erich Auerbach noted, it is the scar that makes Odysseus recognizable by

“foregrounding” his past into an “uninterrupted” flow of present (and, according to

the heroic model, most heroes bear a signifying scar, from Siegfried to Harry

Potter).98 Modern heroes push this idea to its breaking limits and become the scar, a

psychological one this time: Batman is his childhood trauma, Superman is his

loneliness as Krypton’s last son, Xena is her guilt, reflecting a society where a

personal therapist is no longer a dark, shameful secret, but a posh accessory, easily

brought into conversation as a mark of social status, personal distinction, or WoodyAllenesque wit and style. But the FF remove the scar from any purely temporal

signification and imprint it on, and as, the whole body declaring its vulnerability,

while at the same time it signals the body’s healing-transformative potential.

Thus that the grotesqueness of comic-books like the FF (also eulogized at

about the same time in Allen Ginsberg’s groundbreaking 1956 Howl) can be

perceived as ideal, but also as a foreboding of the projection of certain continuing

trends in our Western culture. The beautiful grotesque that, by provoking and

shocking, allows its bearer not to be invisible any more, to stretch above the crowd

and achieve, even momentarily, a shining escape from conformity (a quality much

devalued since the 50s-60s) is perhaps a way to understand such youth culture trends

such as the “grunge” look, extreme tattooing and piercing, the “Bear” movement

among gay men, and even, briefly in the early 90s, cosmetic scarification. After all,

the pluri- and multi- ideologies of the late 20th-early 21st century have made ample

room for the easy coexistence of different physiques, despite the pressures of the

entertainment industry. At the same time, in an era where the human body, compared

to the machine, is losing in importance and superiority and is questioned as the

grounding signifier for “humanity,” deconstructing the body by bringing to surface its

inherent, or latent, potential for deformity—poking at the scar so to speak—is a kind

of cultural pre-emptive strike against the fear of such future mutations (a fear that has

been growing in our culture since the atom bomb effects on human genes first became

known): not only an acceptance of the body’s imperfect status, but also a game of

Northrop Frye, (1957) “Anatomy of Criticism: Mythic Archetypes,” Literature: An Introduction

to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama, 6th ed., X. J. Kennedy and Dana Gioia, eds. (New York:

HarperCollins College Publishers, 1995): 1810.

98 Erich Auerbach, “Odysseus' Scar,” The Critical Tradition: Classic Texts and Contemporary

Trends, David H. Richter, ed. (Boston: Bedford, 1998): 654-67.

97

23

“chicken” with evolution. It is a mentality akin to that which Henri Bergson observes

about the caricaturist:

He makes his models grimace as they would by themselves if they could take

their grimace all the way. He guesses, under the surface harmonies of form,

the deep insurrections of matter. He realizes the imbalances and

distortions...that didn’t manage to reach their completion, since they were

exorcised by a higher power. His art, that partakes somewhat of the diabolical,

raises again the demon that the angel had thrown down.99

This gambit of negative aesthetics became painfully obvious in the 1994 failure of a

then-first FF film, which, in returning the comic bodies to an “angelic” realism sans

medium conventions made their superhero oddity look abysmally inane.100 Only the

Thing looked real because he has never looked real. The grotesque annulment of

classical beauty standards may derive from an overextension of those same ideal

standards that is particularly fit for the comic-book medium, but it ends up one step

beyond. What it aims at is a condition where, because its grotesqueness liberates form

from any secondary significations other than physical utility, body as flesh is

dissolved into the ideal concept of mere (or, rather, utter) capacity (and thus, if we

extend Beebee’s theory, its new “use-value” becomes the foundation of a new

genre—or species, perhaps?),101 and matter does no longer matter. In the grafting of

the unreal onto reality (Baudrillard’s “hyperreality” of American utopianism);102 in an

individuative process that can never be completed because we can never transcend,

even in our most fantastic ventures, the mark of our physicality and our particular era

(be it the 60s or the 2000-somethings); finally, in what it promises to give but always

must withhold from the reader103—a body so unfit, that it fits—does the comic book

establish its never-ending, and utterly fantastic, charm.

Henri Bergson, Laughter, An Essay on the Importance of the Comic, Vassilis Tomanas, trans.

(Athens: Exantas-Nemata, 1998): 27-29. Quote translation mine.

100 The Fantastic Four, Oley Sassone, dir., starring: Alex Hyde-White, Jay Underwood, Rebecca

Staab, Michael Bailey Smith, Joseph Culp (Marvel Entertainment, 1994).

101 Beebee 250.

102 Baudrillard 28.

103 The infamous “dissimulation of the woven texture” (of the text, which “is not a text unless

it hides from the first comer, from the first glance, the law of its composition and the rules of

its game. A text remains, moreover, forever imperceptible.”—63) theorized in: Jacques

Derrida, (1972) Dissemination, Introduction and Additional Notes by Barbara Johnson, trans,.

Athlone Contemporary European Thinkers (London: The Athlone Press, 2000).

99

24

Bibliography

Auerbach, Erich. “Odysseus' Scar.” In Richter, 654-67.

Baudrillard, Jean. (1986) America. Translated by Chris Turner. London and New

York: Verso, 1995.

Beebee, Thomas O. The Ideology of Genre: A Comparative Study of Generic

Instability. University Park: Penn State P, 1994.

Bergson, Henri. Laughter: An Essay on the Importance of the Comic. Translated by

Vassilis Tomanas. Athens: Exantas—Nemata, 1998.

Brady, Matt. Marvel Encyclopedia, edited by Mark Beazley and Jeff Youngquist.

New York: Marvel Comics, 2002.

Braidotti, Rosi. Nomadic Subjects: Embodiment and Sexual Difference in

Contemporary Feminist Theory, edited by Carolyn C. Heilbrun and Nancy K.

Miller. Gender and Culture series. New York: Columbia UP, 1994.

Cixous, Hélène. “The Laugh of the Medusa.” In Feminisms: An Anthology of Literary

Theory and Criticism, edited by Robyn R. Warhol and Diane Price Herndl,

334-49. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers UP, 1991.

Derrida, Jacques. “Structure, Sign and Play in the Discourse of the Human Sciences.”

In Writing and Difference. Translated with an Introduction and Additional

Notes by Alan Bass, 278-93. Chicago: The U. of Chicago P., 1978.

Eco, Umberto. “The Myth of Superman.” In Richter, 866-77.

Fender, Stephen. “The American Difference.” In Modern American Culture: An

Introduction, edited by Mick Gidley, 1-22. New York: Longman, 1994.

Foucault, Michel. “From Truth and Power.” Translated by Colin Gordon. In The

Norton Anthology of Theory and Criticism, edited by Vincent B. Leitch, 166770. New York and London: Norton, 2001.

Frahm, Ole. “Weird Signs. Comics as Means of Parody.” Translated by Michael Hein.

In Magnussen and Christiansen, 177-90.

Freud, Sigmund. (1908) “Creative Writers and Daydreaming.” In Critical Theory

since Plato. Revised ed., edited by Hazard Adams, 712-16. Fort Worth:

Harcourt Brace Jovanovich College Publishers, 1992.

Frye, Northrop. “Anatomy of Criticism: Mythic Archetypes.” In Literature: An

Introduction to Fiction, Poetry, and Drama. 6th ed., edited by X. J. Kennedy

and Dana Gioia, 1810-11. New York: HarperCollins College Publishers, 1995.

25

Groensteen, Thierry. “Why Are Comics Still in Search of Cultural Legitimization?” In

Magnussen and Christiansen, 29-41.

Grosz, Elizabeth. Volatile Bodies: Toward a Corporeal Feminism. Bloomington:

Indiana UP, 1994.

Hillman, David, and Carla Mazzio. The Body in Parts: Fantasies of Corporeality in

Early Modern Europe. New York and London: Routledge, 1997.

Holman, Hugh C., and William Harmon. A Handbook to Literature. 6th ed. New

York: Macmillan, 1992.

Jaffé, Aniela. “Symbolism in the Visual Arts.” In Jung, 255-322.

Jung, Carl Gustav. “Approaching the Unconscious.” In Jung, 1-94.

Kaindl, Klaus. “Multimodality in the Translation of Humour in Comics.” In

Perspectives on Multimodality, edited by Eija Ventola, Charles Cassidy and

Martin Kaltenbacher, 173-92. Document Design Companion 6. Amsterdam

and Philadelphia: John Benjamins, 2004.

Kroker, Arthur. SPASM: Virtual Reality, Android Music and Electric Flesh. Culture

Texts Series. Montréal: New World Perspectives, 1993.

Lacan, Jacques. (1949). “The Mirror Stage as Formative of the Function of the I as

Revealed in Psychoanalytic Experience.” In Davis and Schleifer, 382-99.

Lee, Stan (writer) and Jack Kirby (penciller). The Fantastic Four. New York: Marvel

Comics/Marvel Entertainment Group, 1961.

---. “The Coming of Galactus!” The Fabulous Fantastic Four: Marvel Treasury

Edition 1.2: 52-98.

---. “Captives of the Deadly Duo.” The Fabulous Fantastic Four: Marvel Treasury

Edition 1.2: 4-27.

Mellor, Anne K. “Possessing Nature: The Female in Frankenstein.” In Romanticism

and Feminism, edited by Anne K. Mellor, 220-32. Bloomington &

Indianapolis: Indiana UP, 1988.

Mitchell, W.J.T. “Representation.” In Critical Terms for Literary Study, edited by

Frank Lentricchia and Thomas McLaughlin. Chicago and London: The U of

Chicago P, 1999. 11-22.

Mulvey, Laura. (1975) “Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema.” In Davis and

Schleifer, 422-31.

Murray, Will. “Farewell to the King: Friends Remember That King of Comics, the

Legendary Jack Kirby.” Comics Scene 42 (May 1994): 12-15+, 56.

26

Pustz, Matthew. Comic Book Culture: Fanboys and True Believers. Jackson, NC: U

of Mississippi P, 1999.

Sabin, Roger. Adult Comics: An Introduction. New Accents series. London and New

York: Routledge, 1993.

Scarry, Elaine. On Beauty and Being Just. Princeton, NJ: Princeton UP, 2001.

Voger, Mark. “Living Legend: A Half-century Later, Jack Kirby Is Still the American

Comic Book.” Comics Scene Yearbook 2 (1993): 35-39.

von Franz, Marie L. “The Process of Individuation.” In Man and His Symbols, edited

with an Introduction by Carl G. Jung, 161-254. New York: Dell/Laurel, 1968.

Zachopoulos, Christos. “Introduction.” In Greek Political Cartoons, edited by

Christos Zachopoulos, 9-36. Prologue by Ioannis Varvitsiotis. Lefkomata

series. Athens: The Constantinos Karamanlis Institute for Democracy—Sideris

Publications, 2002.

Filmography

The Fantastic Four. Dir. Tim Story. Marvel Entertainment Group, 2005.

The Fantastic Four. Dir. Oley Sassone. Marvel Entertainment, 1994.