Julian of Norwich Life

advertisement

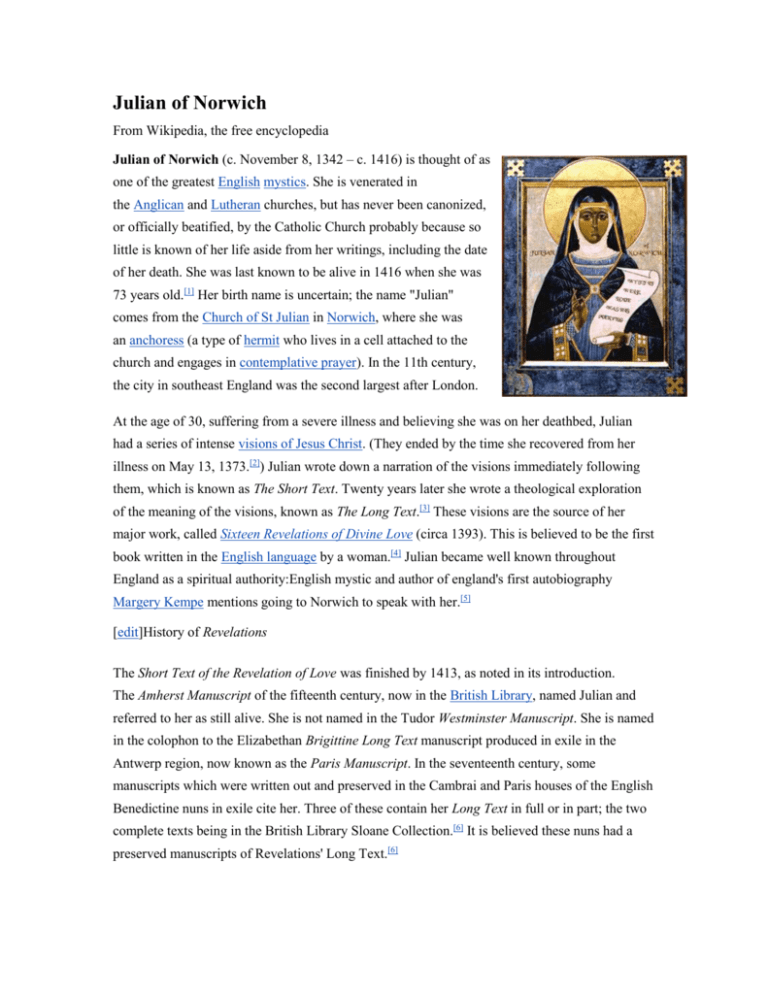

Julian of Norwich From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Julian of Norwich (c. November 8, 1342 – c. 1416) is thought of as one of the greatest English mystics. She is venerated in the Anglican and Lutheran churches, but has never been canonized, or officially beatified, by the Catholic Church probably because so little is known of her life aside from her writings, including the date of her death. She was last known to be alive in 1416 when she was 73 years old.[1] Her birth name is uncertain; the name "Julian" comes from the Church of St Julian in Norwich, where she was an anchoress (a type of hermit who lives in a cell attached to the church and engages in contemplative prayer). In the 11th century, the city in southeast England was the second largest after London. At the age of 30, suffering from a severe illness and believing she was on her deathbed, Julian had a series of intense visions of Jesus Christ. (They ended by the time she recovered from her illness on May 13, 1373.[2]) Julian wrote down a narration of the visions immediately following them, which is known as The Short Text. Twenty years later she wrote a theological exploration of the meaning of the visions, known as The Long Text.[3] These visions are the source of her major work, called Sixteen Revelations of Divine Love (circa 1393). This is believed to be the first book written in the English language by a woman.[4] Julian became well known throughout England as a spiritual authority:English mystic and author of england's first autobiography Margery Kempe mentions going to Norwich to speak with her.[5] [edit]History of Revelations The Short Text of the Revelation of Love was finished by 1413, as noted in its introduction. The Amherst Manuscript of the fifteenth century, now in the British Library, named Julian and referred to her as still alive. She is not named in the Tudor Westminster Manuscript. She is named in the colophon to the Elizabethan Brigittine Long Text manuscript produced in exile in the Antwerp region, now known as the Paris Manuscript. In the seventeenth century, some manuscripts which were written out and preserved in the Cambrai and Paris houses of the English Benedictine nuns in exile cite her. Three of these contain her Long Text in full or in part; the two complete texts being in the British Library Sloane Collection.[6] It is believed these nuns had a preserved manuscripts of Revelations' Long Text.[6] The first printed version of the Revelations was available to the public in 1670, and was edited by Benedictine Serenus Cressy. It did not become well-known until the twentieth century. Cressy's edition was reprinted in 1843, 1864, and again in 1902. However, it was Grace Warrack's 1901 version of the book with its "sympathetic informed introduction" which introduced most early twentieth-century readers to Julian.[7] After this, Julian's name spread rapidly as she became a topic in many lectures and writings. In 1979 an annotated edition of Julian's work was published, and after this her book was widely sold and discussed, at a time of renewed spiritual searching by many. Julian is now recognized as one of England's most important mystics.[8] [edit]Theology A statue of Julian (in white) appears on the front of Norwich Cathedral, along with a statue of St. Benedict. Although Julian lived in a time of turmoil, her theology was optimistic, speaking of God's love in terms of joy and compassion as opposed to law and duty. For Julian, suffering was not a punishment that God inflicted, as was the common understanding. She believed that God loved and wanted to save everyone. Popular theology, magnified by current events including the Black Death and a series of peasant revolts, asserted that God was punishing the wicked. In response, Julian suggested a more merciful theology, which some say leaned towards universal salvation. She believed that behind the reality of hell is a greater mystery of God's love. In modern times, she has been classified as a proto-universalist, although she did not claim more than hope that all might be saved.[9] Although Julian's views were not typical, local authorities did not challenge either her theology or her authority because of her status as an anchoress. The lack of references to her work during her own time may indicate that religious authorities did not count her worthy of refuting, since she did not have much power as a woman.[citation needed] Julian's theology was unique in three aspects: her view of sin, her belief that God is all love and no wrath, and her view of Christ as mother.[citation needed] According to Julian, God is both our mother and our father. This idea was also developed by Francis of Assisi in the thirteenth century.Feminist theology in the 20th and 21st centuries has developed along similar lines. Julian believed that sin was necessary in life because it brings one to self-knowledge, which leads to acceptance of the role of God in one's life.[10] Julian taught that humans sin because they are ignorant or naive, not because they are evil, which was the reason commonly given by the church for sin during the Middle Ages.[11] Julian believed that in order to learn, we must fail. Also, in order to fail, we must sin. The pain caused by sin is an earthly reminder of the pain of the passion of Christ. Therefore, as people suffer as Christ did, they will become closer to Him by their experiences. Similarly, Julian saw no wrath in God. She believed wrath existed only in humans but that God forgives us for this. She writes, “For I saw no wrath except on man's side, and He forgives that in us, for wrath is nothing else but a perversity and an opposition to peace and to love”.[12]Julian believed that it was inaccurate to speak of God's granting forgiveness for sins because forgiving would mean that committing the sin was wrong. Julian preached that sin should be seen as a part of the learning process of life, not malice that needed forgiveness. Julian writes that God sees us as perfect and waits for the day when humans' souls mature so that evil and sin will no longer hinder one's life.[13] Lastly, Julian's theology was controversial in regard to her belief in God as mother. Some scholars believe this is a metaphor, rather than a literal belief or dogma. In her fourteenth revelation, Julian writes of the Trinity in domestic terms, comparing Jesus to a mother who is wise, loving, and merciful. (See Jesus as Mother by Carolyn Walker Bynum. Need page cite and full info.) Julian's revelation revealed that God is our mother as much as He is our father. On the other hand, F. Beer asserts that Julian believed that the maternal aspect of Christ was literal, not metaphoric; Christ is not like a mother, He is literally the mother.[14] Julian believed that the mother's role was the truest of all jobs on earth. She emphasized this by explaining how the bond between mother and child is the only earthly relationship that comes close to the relationship one can have with Jesus.[15] She also connects God with motherhood in terms of (1) "the foundation of our nature's creation, (2) "the taking of our nature, where the motherhood of grace begins" and (3) "the motherhood at work", and writes metaphorically of Jesus in connection with conception, nursing, labor, and upbringing. However, she sees him as our brother as well. The Norwich Benedictine and Cardinal of England Adam Easton O.S.B. may have been Julian of Norwich's spiritual director and editor of herLong Text Showing of Love. Birgitta of Sweden's spiritual director, Alfonso Pecha, the Bishop Hermit of Jaen, edited her Revelationes.Catherine of Siena's confessor and executor was William Flete, the Cambridge-educated Augustinian Hermit of Lecceto. Easton's Defense of St Birgitta echoes Alfonso of Jaen's Epistola Solitarii, and William Flete's Remedies against Temptations, all of which are referred to in Julian's text.[16] The saying, "…All shall be well, and all shall be well, and all manner of things shall be well", which Julian claimed to be said to her by God, reflects her theology. It is one of the most famous lines in Catholic theological writing, and one of the most well-known phrases of the literature of her era.[citation needed] The 20th-century poet T.S. Eliot incorporated this phrase, as well as Julian's "the ground of our beseeching" from the 14th Revelation, in his "Little Gidding", the fourth of his Four Quartets poems: Whatever we inherit from the fortunate We have taken from the defeated What they had to leave us—a symbol: A symbol perfected in death. And all shall be well and All manner of thing shall be well By the purification of the motive In the ground of our beseeching. [edit]Works Showing of Love, ed. Sister Anna Maria Reynolds, C.P., and Julia Bolton Holloway. Florence: SISMEL, 2001. Showing of Love, Trans. Julia Bolton Holloway. Collegeville: Liturgical Press; London; Darton, Longman and Todd, 2003. The Writings of Julian of Norwich, ed. Nicholas Watson and Jacqueline Jenkins. Brepols, 2006. Revelations of Divine Love