Condideratii generale privind raspunderea civila delictuala

advertisement

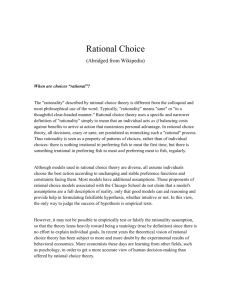

RATIONALITY’S SPACE OF INDETERMINATION Assistant Florin Popa, Ph.D The Academy of Economic Studies, Bucharest florinpopa10@yahoo.com Abstract: The article proposes a critical analysis of an influential perspective on practical rationality, based on the assumption that the rationality of decisions and actions can be, in principle, perfectly defined by applying a set of formal criteria of unidirectional adequacy of means to ends. Our critique notes that a crucial fact is ignored: most important decisions confront us with a space of indetermination, an area in which deliberation can not clearly delineate between rational and irrational solely on the basis of predefined and context-independent criteria. A more appropriate representation of rationality seems to be offered by the complementary and flexible application of formal criteria (which offer a minimal set of necessary, but not sufficient, conditions) and norms open to adaptive adjustments. These adjustments are not generated by the application of postulated criteria, but by decisional practice and the confrontation with alternative norms developed in other contexts. Keywords: rationality, reasonableness, the space of indetermination, decision theory, decision models. The problem of rationality is present, more or less explicitly, in any discussion of human capacities of knowledge, decision and action. Even a minimal analysis of how individuals make decisions and pass from decision to action assumes an implicit demarcation of practical rationality. This involves, among others, questions on what criteria and norms to use, the relationship between the reasons for taking a decision and its consequences or the relationship between the epistemic and practical levels of rationality. Determining the truth of certain statements is implicitly linked to our understanding of how these statements are to be justified on the basis of evidence and to our way of making decisions or acting on the basis of these statements. Therefore, the problem of truth is inextricably linked to the concept of rationality, theoretical or practical. The difficulty to operate with clearly demarcated and autonomous fields (rationality, truth, fairness) says something about the very nature of rationality: it must not be considered only - and, anyway, not primarily - in terms of content (which are the required criteria for decision or action). Essentially, rationality implies preconditions of adequacy applicable to decision-making and action. Just as any meaningful debate and argumentation makes implicit reference to constraints of theoretical rationality, decision-making is subject to criteria and norms of rational adequacy. Adequacy concerns the relationship between the reasons for decisions (opinions, preferences, desires) and the actual decision, as well as the relationship between different (and sometimes divergent) goals guiding decisions. This does not entail, however, the adoption of an illusory "right model" or some unlikely infallible criteria of rational action. Rather, we have exploratory and local adjustments of rational adequacy rules that remain essentially preliminary and changeable. Although any model of rational decision remains open to criticism and adjustment, the rationality assumption, as a general requirement concerning the adequacy of opinions, preferences, goals in respect to decisions and actions, is maintained systematically. The rationality assumption is not part of a particular model of decision, but implicit condition of possibility of any model. The assumption that practical rationality can be described adequately using a predetermined set of formal criteria has to do, to some extent, with the influence of a methodological tradition based on the postulation of cognitive faculties as the basis of rational behavior, and a corresponding model of formal rationality. Specifically, it is a model based on the idea of “legitimate inference” - an inference guided by formal, universal, a priori principles1. The strict and indiscriminate application of this concept in social sciences and philosophy has had negative effects, says H. Kincaid, insofar as it ignored the essentially empirical nature of inferences underlying methodological rules. It is a reductionist attempt at founding practical rationality on a predefined set of formal criteria and general applicability. Many of the explanatory models developed in decision theory and rational choice theory are based on assumptions which, taken together, compose what John Searle (2002) called the classical perspective on rationality2. It is not clearly defined theory of rationality, but rather a theoretical framework partially made explicit, based on conditions of rational adequacy concerning the relations between opinions, desires and preferences and decisions, between decisions and actions etc. The classical perspective can be described as the overlapping area of several similar approaches, which partially share a set of assumptions of rationality. According to this approach, to be rational is to argue and make decisions in accordance with a relevant set of formal criteria - the rules of logic, probability theory, rational choice theory, etc. The classical perspective approaches rationality formally and instrumentally. The formal aspect concerns the nature of adequacy criteria: they describe abstract structures or relations between variables (preferences, utilities, alternatives), disregarding the specific context of their application. As such, respecting certain rules, procedures or norms (e.g. the internal consistency of preferences) would necessarily render our opinions or decisions rational. The instrumental aspect refers to the range of rational decision: it concerns the choosing of means according to ends, but not the selection and evaluation of ends themselves (these are given). The classical perspective assumes that rationality is a distinct cognitive faculty. In this perspective, its limits are deemed to have been already fixed, as 1 2 2 Kincaid, (2000), 67. Searle, (2002), offers an interesting analysis of the classical perspective’s assumptions. Vol. II, no. 3/september, 2010 part of our implicit cognitive endowment, and its exercise could be prevented only by “disruptive” factors (insufficient or erroneous information, emotions, errors of judgment etc.). Just as we use language to communicate, we use this cognitive faculty to form opinions, make decisions and act. But rationality is not simply given, is not a ready-made faculty applicable to decisions and actions. Its fuzzy boundaries are constantly specified and modified in the very process of applying it. What means that a certain decision is rational can only be adequately specified within the specific context of that decision and of the person deciding. The implicit or explicit norms of rational adequacy that we apply in evaluating decisions depend on this context. It is not a completely formalized model, applied on the basis of a predefined set of criteria, and at the same time it is not rationality model that can be completely specified either at individual level (by applying necessary and sufficient criteria to individual contexts) or at collective level (as a simple aggregation of individual rational action, in the manner of rational choice models). Overall, the classical perspective includes models of decision that share (partially or fully) the following assumptions: the “faculty of rationality” is given, it is already fully specified at the level of each decision-maker, rational decision concerns the unidirectional adequacy of means to ends, practical rationality consist exclusively of formal criteria with general applicability, their application is independent of the decision context, the subject’s aims are not themselves subjected to rational scrutiny (they are taken as such), the subject’s decisions or actions are completely determined by the intentional antecedents of any specific decision (desires, preferences, beliefs, moral evaluations etc.). Let’s analyze for a moment the assumption that, in principle, the space of practical rationality can be perfectly specified, in the sense that any decision or action can be, under appropriate conditions, qualified as rational or irrational. The reasons for accepting it are not obvious by any means; in practice, the evaluation of the rationality of many decisions or actions proves difficult, and this difficulty cannot be reduced to insufficient information or faulty processing. Not everything that is obviously not rational is obviously irrational. Contrary to the normative tradition of the classical perspective, according to which practical rationality could provide a behavioral guide based on a clear set of rules, the decisional practice seems to suggest a more modest approach. There are many cases in which practical rationality proceeds by elimination (negatively), without being able to provide at the same time a clear and comprehensive method for demarcating its own space1. Interestingly, the difficulty does not have to do with the inadequacy of the criteria used, but with the impossibility of using a predefined criterion of demarcation of general applicability. There is a space of indetermination, which includes decisions that can not be regarded as rational on the basis of a given set of formal criteria. Alternatively, we could say that it is about decisions whose rationality is to be established or disproven, but is for the moment indeterminable. What can be said with reasonable certainty is that these 1 Cf. Elster, (1983). Cogito – Multidisciplinary Research Journal 3 decisions are not irrational (in the sense that not violate the minimum criteria of rationality – for instance, adopting a self-defeating behavior or following contradictory aims). This space of indetermination was traditionally considered the result of our psychological and cognitive limitations concerning access to information, processing and deliberation. The implicit assumption was that, in principle, we have the capacity to limit or eliminate this space - that its existence is accidental, temporary, and based only on contextual limitations (limited capacity of obtaining and processing information, errors of judgment etc.). The inability to find a criterion of demarcation applicable in any context was considered to be a contextual and transitory problem, not something that has to do with the demarcation criterion used or the underlying rationality model. The models of rational decision based on the postulation of a rational actor share an essential premise, according to which the rationality of our decisions or actions may be determined comprehensively by applying a set of predefined criteria with general applicability. In this perspective, rationality is detached from the "objects" to which it is applied – individual opinions, decisions, preferences, actions. The incapacity of determining the rational alternative in every possible situation would depend, in other words, on the existence of factors that limit or disrupt the optimal functioning of our cognitive faculties. In an ideal world in which these factors would be absent or insignificant, subjects would make perfectly rational decisions. This optimistic view about the role and possibilities of rationality is undermined by the observation of how people actually make decisions and relate to normative models of rational decision-making. The space of indetermination is not simply a result of limited capacities or "disruptive" factors. Its existence is natural and reflects the diversity of human practice whose intuitive reasonableness cannot be adequately explained on the basis of any predetermined set of rationality criteria. Suppose we are in a position to decide which candidate to vote for in municipal elections. One of the candidates is recommended by a long experience in local government, another has a very pleasant public presence and an inspired speech, but limited experience in local government. Apparently, the third candidate does not have any of these qualities, but is a former university colleague. My decision will be guided by criteria and norms, but which ones should have priority in this context? I wouldn’t vote for him just because I know him but - on the other hand - it is precisely my direct knowledge of him that gives me good grounds for voting (I know he is bright, a good negotiator and has a strong sense of fairness). I have only indirect and superficial information about the other two candidates (they appear to have certain skills or character traits). Is it better to vote on the basis of my direct experience, filtered by my own subjectivity, or on the basis of public information, where it is difficult to verify the credibility of sources and know how well founded the public opinion is? Also, should I give priority to professional expertise, personal abilities, negotiation and managerial skills or existing political support? Most likely, a combination in varying proportions of these norms, probably along with others. An adequate answer can only be given only within that specific context. It is essential that my 4 Vol. II, no. 3/september, 2010 choice will not be guided by a recipe of general applicability, but rather it will be the result of "negotiations" between alternative norms and contextual limitations. It involves discernment, not the mechanical application of a decision algorithm. The space of indetermination is the expression of the inadequacy of classical perspective, which operates with clear-cut differences in a context characterized by shades, nuances and gradual progressions. The indeterminacy concerns, in this case, the fact that the borders of practical rationality are not already drawn, but reveal themselves only when evaluated against specific contexts. It is not the fact that it would be impossible to qualify some decisions as rational or irrational due to lack of information, situational complexity or limited cognitive capacities. (In these cases, it is assumed that the norms of rational adequacy are clearly defined, but the subject has difficulties in applying them). It is not the incompleteness of decisional premises, but the indeterminacy of norms that makes it impossible to clearly demarcate what is rational or not. An alternative is offered by complementary and flexible application of formal criteria (which offer a minimal set of necessary but not sufficient conditions) and norms open to adaptive adjustments: "formal reasoning about the axioms postulated (including their compatibility and consistency), as well as the informal understanding of values and norms (including their relevance and plausibility) are both oriented in this productive direction”1. Unlike criteria, norms, by their very nature, cannot be fully translated into a formalized structure, they do not represent rigid delimitations, but tentative specifications, open to changes. Norms are contextually adjustable, but this does not entail their genetic dependence on the context – more precisely, not on a specific context or any number of specific contexts. Norms are context-dependent only insofar as they cannot be fully specified outside a given context; they are neither the ever-changing result of immediacy and concreteness, nor the manifestation of a “rational transcendence” that distributes itself uniformly and without nuances in all possible decision contexts. If a criterion represents a formal condition of adequacy, a norm concerns the substantive adequacy of behavior to the concrete situation, the exercise of discernment with regards to the means but also ends. It values that reasonableness that is irreducible to a purely instrumental understanding of rationality. The mere application of a criterion of logical consistency to opinions cannot establish the rationality of decisions in a given context, for two reasons: firstly, because it works by elimination, not constructively, and cannot provide an unambiguous means of selecting between several alternative decisions based on consistent opinions and transitive preferences; and secondly, because the rationality of decisions, understood strictly instrumentally, may conflict with its reasonableness. The first involves a unidirectional adjustment of means (decisions) to ends (preferences, opinions, value commitments), which does not include an assessment of the rationality of the latter. By contrast, reasonableness requires a bi-directional adequacy between decisional premises and decisions themselves, which has to do with more than instrumental optimization: it aims to 1 Sen, (1999b), 366. Cogito – Multidisciplinary Research Journal 5 ensure that a certain decision is consistent and appropriate with regards to the overall set of aims and commitments of the decision-maker. This involves an analysis of the rationality of aims – of their “internal” consistency (as related to all other aims) and "external" consistency (in relation to the decision-maker’s conduct), as well as their relative weight. As such, the "rational adequacy" of a given decision is not assessed against predefined elements (constant preferences, fixed aims), but against the horizon of a gradual convergence with other practices and norms of rationality of the subject, as well as of other subjects. The pretense of being able to fully specify a decision model with general applicability a priori can lead to counter-intuitive results, perceived as unreasonable. The rationality of decisions (analytical, formalized) cannot ignore the reasonableness of decisions (informal, contextual, intuitive). If the classical view of rationality appeals to criteria and rules applicable independently of any context, reasonableness calls for norms that are defined and reconfigured largely on the basis of relevant prior experience, and its application is nuanced and contextual (which does not imply that they are generated by the context, but only that they cannot be properly specified outside given contexts). Thus understood, reasonableness cannot cover the entire area of practical rationality, but rather provides the conditions of its exercise. Unlike rationality (who implicitly carries the ambition of full formalization), reasonableness is flexible, contextual and non-reductionist. It calls for aims, norms and principles - generally, value commitments which, in the tradition of instrumental rationality, are either ignored or taken for granted, without attempting an evaluation of their own rationality 1. It is useful, we believe, to reconsider and redeem reasonableness and its role in rational conduct. This reconsideration recognizes the essential role of that intuitive and experiential given of any rational evaluation, which brings together common sense (i.e. the spontaneous, unmediated recognition of just proportions) and discernment (i.e. the capacity to determine what is relevant, appropriate to the situation or essential). If the classical model involves fixed and predefined criteria, applicable regardless of context, the norms are adjustable, open to new practice that can change the contours of the space of indetermination. Also, if rationality remains essentially individual (its collective instances being always defined by reference to the rationality of an individual or individuals), reasonableness feeds itself on the social, interactive background that informs and demarcates all individual decisions. It implicitly refers to that interactive environment in which rationality norms and practices are defined but also called into question. Ultimately, reasonableness refers to rationality that is aware of its limits, open to evidence and opposed to dogmatism. In contrast with the theoretical hybris of the classical perspective on rationality - mainly rational choice theory – reasonableness implicitly recognizes the limits of any formalized model of 1 W. H. Newton-Smith makes the distinction between minirat and maxirat evaluation of the rationality of decisions. A maxirat evaluation includes not only an assessment of means (alternative choices for decision), but also of the grounds for decision – opinions, preferences, aims (Newton-Smith 1994, 315-320). 6 Vol. II, no. 3/september, 2010 rationality and rejects as inadequate the transformation of these limits (preliminary and changeable) in fixed boundaries of rationality as such. The constant call to reasonability can prevent the transformation of reason into an object of rationalism, i.e. of a conception of rationality which tends to immunize itself to criticism, becoming prisoner of its own assumptions. BIBLIOGRAPHY [1] Elster, Jon, (ed.), (1986), Rational Choice, Oxford, Basil Blackwell. [2] Harold, Kincaid, (2000), Formal Rationality and Its Pernicious Effects on Social Sciences, in Philosophy of the Social Sciences 2000; 30. [3] Habermas, Jurgen, (2000b), Conştiinţa morală şi acţiune comunicativă, Ed. All, Bucureşti. [4] Newton-Smith, W. H., (1994), Raţionalitatea ştiinţei, Bucureşti, Ed. Ştiinţifică. [5] Popper, Karl R., (1998), Mitul contextului, Ed. Trei, Bucureşti. [6] Searle, John, (2002), Rationality in Action, Cambridge, Mass., MIT Press. [7] Sen, A.K., (1977), Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory, Philosophy and Public Affairs, Vol. 6, No. 4 (Summer, 1977). [8] Sen, Amartya, (1995), Rationality and Social Choice, The American Economic Review, March 1995. [9] Sen, Amartya, (1999a), Development as Freedom, Oxford: Oxford University Press. [10] Sen, Amartya, (1999b), The Possibility of Social Choice, The American Economic Review; iunie 1999. Cogito – Multidisciplinary Research Journal 7