Consciousness-and-its-Place-in-Nature

advertisement

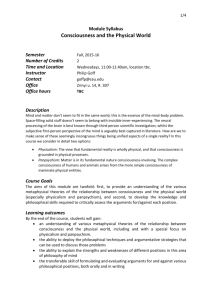

Consciousness and its place in nature Galen Strawson et al. Ed. Anthony Freeman 1. The Road to Panpsychism Although the main title of this book gives an accurate indication of its content, it could also mislead. In recent years there has been no shortage of books devoted to the relationship between consciousness and the natural world – rather too many, some would say – but few (if any) have covered the same ground as this one. In this regard the book’s subtitle is more revealing: Does physicalism entail panpsychism? A natural immediate reaction to this might well be along the lines of ‘What?! Don’t be silly.’ Since physicalists tend to view consciousness as a byproduct of neural activity in the brain, it is hard to see how physicalism could lend support to – let alone entail – the very radical view that consciousness is to be found everywhere, or at least, in every material thing. And of course on a more general level, the two doctrines are commonly associated with very different philosophical temperaments. Physicalism is the home of the serious, hardheaded, naturalistically inclined and scientifically informed philosopher. Panpsychism, by contrast, tends to be viewed as an eccentric refuge for the woolly-minded or mystically-inclined. If people who hug trees and talk to rocks run the risk of being thought slightly odd, those who believe that rocks and trees themselves have feelings are likely to be deemed downright weird, if not worse. Since panpsychism can so easily seem the silliest, most absurd, of metaphysical doctrines, it is not surprising that it has largely escaped sustained sober analytical scrutiny. But then again, given the increased interest over the past couple of decades in ‘alternative’ approaches to the matter-consciousness problem – i.e., approaches other than reductive physicalism in any of its guises – such scrutiny is arguably overdue. In Consciousness and its place in nature this lacuna is filled. The book opens with a usefully provocative (and exuberant) target essay ‘Realistic Monism: Why Physicalism Entails Panpsychism’ by Galen Strawson; this is followed by seventeen critical commentaries, which are in turn followed by a substantial reply by Strawson. Unusually for a volume of this sort, all the critical essays remain tightly focused on the intended theme, and most are by well-known figures in the field: Frank Jackson, William Lycan, Colin McGinn, David Papineau (together with Elizabeth Schechter), George Rey, William Seager, Peter Simons, David Skrbina, J.C.C Smart, Henry Stapp, Daniel Stoljar and Catherine Wilson. A few are by relative newcomers – Sam Coleman, Phillip Goff, Fiona Macpherson – but since these contributions are among the strongest, the quality of the work as a whole is very high. It probably won’t come as a surprise to learn that most of Strawson’s commentators remain unconvinced by his main argument. What is striking, however, is that none are at all dismissive of it. The case for panpsychism may not be irresistible, but it is by no means negligible. Anyone unconvinced by this should certainly read this book. But so too should anyone with an interest in (truly) foundational issues in the philosophy of mind: there is much here that will engage and interest them. The line of argument expounded by Strawson in his opening contribution simple, but powerful. One thing all physicalists can agree on is that mentality is fundamentally a physical phenomenon, and hence that mind-body dualism is false. One of the lessons of modern science is that all physical things are made from the same elementary ingredients (quarks, photons, strings, etc.); suitably rearranged, the particles in a lump of rock could form a nice ripe tomato, or – if the lump is big enough – a thinking, feeling human being. Most of us assume that whereas animals (and in particular, human animals) often enjoy experiences, potatoes, gas clouds and lumps of granite never do, and neither do individual electrons, quarks or photons. If animals have experiences, but vegetables and minerals don’t, and neither do their smaller constituents, then experience must emerge when suitable numbers of basic particles are arranged in a suitable way. Strawson accepts that emergence can and does occur in nature. Individual H2O molecules don’t possess the property liquidity but water does, and water is nothing but a collection of H2O molecules at a certain temperature and pressure. However, he goes on to argue, while there is a plausible and easily comprehensible story to be told as to how atoms and their interactions give rise to liquidity – roughly, the molecular bonds are loose enough to allow molecules to slide past one another – no such story can be told about how experience could arise from combining atoms (or their smaller constituents) in certain ways. Whereas the emergence of liquidity doesn’t involve any fundamentally new ingredients coming into existence – in the case of water it involves nothing more than atoms of hydrogen and oxygen engaging in one of the modes of interaction 2 that is available to them – experiences cannot be brought into existence in so economical a manner. Phenomenal properties, such as redness-as-experienced, have a distinctive intrinsic character all of their own, a character that is distinct from the properties physics ascribes to elementary particles (mass, charge, spin, etc.) Consequently, if we suppose phenomenal properties could be brought into existence by configuring matter in certain ways, we would be dealing with a far more radical generative process – Strawson calls it brute emergence – than in the case of liquidity: for in the experiential case fundamentally new modes of being are being brought into existence (at least on the assumption, currently in play, that the most basic forms of matter lack phenomenal properties). Serious-minded physicalists generally subscribe to the view that every part and aspect of the world is wholly and completely determined by the properties and interactions of elementary material things. Since genuine (liquidity-style) emergence conforms to this total determination of the macro- by the micro-, it is a phenomenon physicalists can and should accept. Since brute emergence does not so conform, physicalists should reject it utterly.1 If Strawson is right about this, what follows? Suppose you have a drawer containing – so you suppose – only white socks, but on opening it you find a red sock; since ordinary interactions among white socks don’t lead to the creation of red socks, you have little option but to conclude that the red sock must have been in the drawer all along. Analogously, if phenomenal properties can’t emerge from the interactions of elementary physical ingredients, we have no option but to accept – improbable though it may sound – that experience in some (no doubt quite primitive) form already exists in the elementary ingredients themselves. It seems that if we hold that consciousness is a physical phenomenon, we must also accept that the physical world is experiential, and not just in systems exhibiting the highest levels of complexity (e.g., human brains), but all the way down. Strawson concedes that, strictly speaking, this reasoning only establishes (what he calls) microspsychism, the doctrine that some species of elementary physical particles have an experiential aspect to their nature. But if – as he thinks likely – all physical things have the same fundamental nature, then we can Strawson characterizes emergence properly so-called thus: ‘Emergence cannot be brute. It is built into the heart of the notion of emergence that emergence cannot be brute in the sense of there being absolute no reason in the nature of things why the emerging thing is as it is (so that it is unintelligible even to God). For any feature Y of anything that is correctly considered to be emergent from X, there must be something about X and X alone in virtue of which Y emerges, and which is sufficient for Y.’ (18) 1 3 reasonably conclude that all forms of matter and energy have an experiential aspect. This yields panpsychism proper, which (for Strawson) is the claim that all physical things have both an experiential and a non-experiential aspect or component. It is the latter proviso which differentiates panpsychism from orthodox idealism. A natural question at this point is how this position can coherently be viewed as a species of physicalism. After all, the mental properties panpsychists attribute to elementary physical particles certainly don’t figure among the properties physicists ascribe to these particles. Recognizing this, Strawson distinguishes two forms of physicalism: ‘physicSalism’ and ‘real physicalism’. According to the physicSalists, the fundamental properties of matter are limited to those recognized by a successful and complete fundamental physics. Strawsonian ‘real’ physicalists take a more expansive view. Like the physicSalists they believe there is just one basic kind of stuff in our universe, and that this stuff is physical. But they also take the experiential to be as real as any other form of concrete reality, and hold that it cannot be reductively identified with any non-experiential mode of reality – such as collections of particles possessing only the properties recognized by physicSalists. Physicalists of this persuasion not only hold that everything that is concrete (or non-abstract) is physical, experience included, they also reject the (for Strawson) hugely implausible reductionism to which most physicSalists subscribe. Strawsonian physicalism may not be to everyone’s taste, but anyone who shares his commitment to a naturalistic world-view and a non-reductionist stance with regard to consciousness will find it largely congenial. In any event one thing is clear: panpsychism is at least an option for anyone who adopts this liberal form of physicalism. Returning to the main line of argument, Strawson later concedes that his claim that ‘physicalism entails panpsychism’ is misleading. It is not (real) physicalism which has this entailment, but the latter combined with two further claims: (a) that experience cannot emerge from the non-experiential, (b) that the intrinsic nature of matter is fundamentally homogeneous – the latter claim taking us from micropsychism to panpsychism. When these additional premises are inserted, Strawson’s argument begins to look broadly similar to the one explored in Nagel’s ‘Panpsychism’ (1979), to which Strawson acknowledges his debt. Nagel’s argument has four stages: (i) Material Composition (all organisms are composed of the same small family of elementary physical ingredients); (ii) Nonreductionism (mental states are not physical properties of organisms, nor are they implied by physical properties); (iii) Realism (it is organisms which possess 4 mental states, not immaterial souls); (iv) Nonemergence (all the properties of a complex thing derive from the properties of its constituents and their relations with other things, hence there are no truly – or brutely – emergent properties). Strawson’s real physicalism together with the commitment to the homogeneity thesis are largely equivalent to Nagel’s (i), (ii) and (iii). There are, however, differences. Strawson devotes a good deal of space to motivating the nonemergence claim, whereas Nagel simply states it. A second difference is terminological-cum-doctrinal. Nagel operates with a narrow, physicSalist, conception of physical properties, and so for him panpsychism and physicalism are in competition. Strawson is also a non-reductionist, but his more accommodating construal of physical properties means that for him physicalism and panpsychism are entirely compatible. 2. Objections Nagel himself remarks that ‘panpsychism should be added to the current list of mutually incompatible and hopelessly unacceptable solutions to the mind-body problem’ (1979: 193). Strawson takes issue with the ‘hopelessly unacceptable’ verdict. In closing he remarks that panpsychism ‘seems to me to be the most parsimonious, plausible, and indeed “hard-nosed” position that any physicalist who is remotely realistic about the nature of reality can take up in the present state of our knowledge.’ (29) Nonetheless, there are problems to be overcome, and he draws our attention to some of the more serious. As one would expect, his commentators mention several more, and dwell on them at greater length. While the lines of argument pursued by the various commentators are all very much relevant to Strawson’s position, they are also quite diverse, and I lack the space here to mention them all. There are, however, a number of recurrent themes, and it is these that I will focus on. Strawson has little patience for reductionist approaches to the experiential; indeed, as we have seen, he incorporates a non-reductionist stance into his account of what ‘real/realistic’ physicalism involves. Unsurprisingly, a number of commentators – including Lycan, Rey, Rosenthal and Smart – take exception to Strawson’s characterization of reductionism as ‘a large and fatal mistake … the strangest thing that has ever happened in the whole history of human thought’ (45) Several others – Caruthers and Schechter, Coleman, Papineau – suggest that Strawson has failed to adequately address the a posteriori physicalism much in vogue in some contemporary circles, the doctrine (roughly speaking) that the experiential does reduce to the non-experiential, even though we are unable to comprehend how, thanks to the incommensurability of the relevant concepts. In 5 his Reply – to which I will return in more detail – Strawson is entirely unrepentant, but he does provide some indications as to where (in his eyes) a posteriori physicalists go wrong. Roughly, their approach to the experiential is overly linguistic-cum-conceptual, they overlook – or refuse to acknowledge – that we have direct access to the true nature of the conscious states: we know their nature simply by having them. Given the key role played by emergence in Strawson’s main argument one might have expected that this topic would feature prominently in the subsequent discussion. As it turns out, there is surprisingly little discussion of it: most of the commentators seem happy to accept what Strawson says on this topic. Then again, perhaps this is not so surprising. It’s easy to see how liquidity might be emergent with respect to the entities postulated by physics; if it was anything like as easy to see how experience could be similarly emergent the mind-body problem would not be the live issue it continues to be. Most would agree that the relationship between phenomenal consciousness and matter is puzzling and problematic – in a manner that the relationship between liquidity and its physical underpinnings is not. While not denying this point, two commentators – Coleman and Jackson – suggest Strawson is too dismissive of the notion that experience is emergent in a more radical way from the (non-experiential) physical. Jackson looks favourably on a model in which there are ‘fundamental laws of nature that go from certain complex arrangements of the non-conscious to consciousness.’ (64). Coleman considers the merits of a similar proposal: ‘Perhaps experience is a distinct and autonomous feature or level of existence, which through natural law comes into being under specific condition [e.g. when microphysical ingredients enter brainlike configurations]’ (42). But isn’t this multiple-level view simply a form of dualism? Views matters thus is not an option for Strawson, given the way he characterizes the physical as ‘whatever is out there in our universe, irrespective of its intrinsic nature’. In fact, the sort of position Jackson and Coleman have in mind is similar to that advocated by the school of British Emergentists – in particular C.D Broad. Strawson does not ignore this position entirely. He remarks: ‘The most ingenious attempt to get around this [i.e., the reasoning which leads to panpsychism] that I know of is Broad’s … but it does not, in the end, work’, and refers us to McLaughlin (1992) for an explanation of why it doesn’t work. This is intriguing, for although McLaughlin argues that the fall of British Emergentism was inevitable, this was not due to any philosophical flaws in the doctrine: ‘British Emergentism does not seem to rest on any “philosophical mistakes”. It is one of my main contentions that advances in science, not 6 philosophical criticism, led to the fall of British Emergentism’ (1992: 50). Prior to the advent of quantum mechanics it was a complete mystery why the different chemical elements look and behave as differently as they do, hence an emergentist view of chemistry looked to be a very viable option; obviously when quantum theory made a reductionist approach to chemistry look more viable the situation changed dramatically. The same applies, mutatis mutandis, for the distinctive features of living matter and molecular biology. If Strawson is correct in his contention that consciousness is not like life (or chemistry), and will always elude the reductionist’s net, then a dose of British-style Emergentism may be just what the doctor ordered. This sort of emergentism no doubt brings disadvantages of its own – the universe becomes less deeply-unified, to mention but one – but if the only viable alternative is panpsychism, these disadvantages may not seem so serious.2 Moving on, several of Strawson’s commentators are of the view that his main line of argument suffers from tensions which reduce its effectiveness. One such derives from the differential epistemic access Strawson claims we have to the physical and phenomenal realms. Descartes believed we have a transparent, essence-revealing access to both the physical and the mental – indeed, it was because of this that we can be sure the mental and physical belong to two distinct realms. Strawson only meets Descartes half-way here: he agrees that we have transparent access to the experiential, but denies that have such access to the physical (or non-experiential) realm. This lack of transparency is important to the plausibility of panpsychism, for even the most powerful microscope will fail to reveal the experiential properties of water, wood or lead, and the same goes for other modes of empirical scrutiny. But this is only a problem if we suppose these modes of scrutiny provide us with a complete insight into the nature of matter, which Strawson denies: ‘we have no good reason to think that we know anything about the physical that gives us any reason to find any problem in the idea that experiential phenomena are physical phenomena’ (4). However, as Stoljar observes, this ‘Ignorantist’ standpoint leaves Strawson in a delicate position. For if we are radically ignorant about the true nature of the non-experiential, how can While most physicists probably do shun the more radical forms of emergence, the ‘multiple autonomous level’ picture is one that other contemporary scientists – in particular biologists – have found appealing, e.g. Noble (2006). There are also physicists prepared to look kindly on radical emergentism, a prominent example being Robert B. Laughlin, the Nobel prize-winning condensed matter physicist; indeed, one of Laughlin’s examples of a strongly emergent phenomenon is water (2005: 33-46; also see (2000)) However, it is probably fair to say that Laughlin’s brand of non-reductionism is not (as of now, at least) widely endorsed by other physicists. 2 7 we be warranted in supposing that its nature is such that it is impossible for the experiential to emerge from it? If our ordinary (physicSalist) conception of matter is hopelessly inadequate, surely we can’t be sure about this. Ignorance inevitably weakens the case for non-emergence. In reply, Strawson confesses to being an Ignorantist, but not a radical Ignorantist: we are not completely in the dark about the nature of matter, we know enough to know that there is something deeply problematic in the notion that the non-experiential could give rise to the experiential. A second tension – discerned and developed in different ways by Carruthers and Schechter, Goff, Papineau, Lycan and McGinn – concerns the relationship between the ‘micro- ’ and ‘macro-experiential’. Although a panpsychist might conceivably hold that elementary physical particles possess conscious lives as rich and complex as our own, in practice few do, and Strawson is no exception. The doctrine is more plausible if we suppose elementary particles possess only elementary mentality, and that complex forms of consciousness come into being when the simpler forms combine in various ways, and this is what Strawson proposes. But while taking this line enhances the plausibility of panpsychism, it also introduces a vulnerability. We are driven in the direction of panpsychism in the first place because it is very difficult to comprehend how consciousness could emerge from micro-physical elements which entirely lack it. Does panpsychism eliminate problematic modes of emergence, or does it simply re-locate them? There is a case for thinking the latter. For how, precisely, is it that complex macro-experientiality (of the sort we enjoy) emerges from the micro-experientiality (of the sort elementary particles enjoy)? This issue is sufficiently important to have been given a name of its own: several commentators call it ‘the Combination Problem’. And as soon becomes apparent, the problem is both multi-faceted and serious. One difficulty is epistemic. Let’s suppose a form of panpsychism is true, and my current state of consciousness is composed of a hundred trillion smaller and simpler states of consciousness, the latter belonging to individual elementary particles in my brain. It is not obvious (to put it mildly) that my consciousness is composed of the experiences of trillions of smaller minds. This absence of evidence is a problem for those who believe, as Strawson does, that we have transparent access to the nature of our experience. Other difficulties are metaphysical. Strawson accepts the principle that for every experience there is a subject whose experience it is (‘no experience without an experiencer’). This means there is a different and distinct subject for every elementary particle in my brain. Does it really make sense to suppose that the 8 experiences of a multiplicity of distinct subjects could be combined in the consciousness of a further subject? Arguably not, for it seems plausible to think that subjects and experiences are governed by an Exclusivity Principle along these lines: if an experience e1 belongs to a subject S1, it belongs ONLY to S1, e1 cannot also (and simultaneously) belong to a distinct subject S2. It is difficult to see how your current experiences and mine could possibly be parts of the consciousness of a larger and more encompassing mind; why shouldn’t the same hold in the case of smaller minds? If this difficulty proves insuperable then macro-level experiences won’t be composed of micro-experiences, they will be entirely distinct creations, which come into being – presumably in virtue of an appropriate natural law – when elementary particles and their associated micro-experiences enter into certain configurations. But clearly, emergence in this form is similar to that posited by Broad; and since it is no longer clear what micro-experiences are contributing to the situation, we might as well dispense with their services. Combination-related difficulties do not end here. There is an identity preservation issue: how can micro-experiences retain their original phenomenal character when they enter into larger configurations? How can very faint micropains hang on to this character when they form parts of an intense macro-level pain? And also a derivation difficulty. To illustrate, suppose the micro-level experiences are all different shades of phenomenal grey; how do we combine these to get the full range of human experiences: phenomenal yellow, orange, sounds of thunder, sounds of speech, bodily sensations, conscious thoughts etc.? As McGinn notes (96), there are a lot of phenomenal primitives at the macro-level, and its difficult to see how these could result from combining experiences with different and simpler qualitative features. Conceding that he doesn’t have full solutions to these Combination-related problems, Strawson notes that his paper was intended to be ‘schematic and exploratory’ (246), rather than a full-blown elaboration and defence of a panpsychist metaphysic. He also suggests that even if panpsychist emergence is problematic, it is nothing like as problematic as the alternative: emergence in the context of two radically disparate modes of being (the experiential and the nonexperiential) looks utterly hopeless, in a way that emergence within a single realm (the experiential) is not. There are two further proposals. At various points Strawson suggests that to make progress on the mind-body problem we will need to abandon the classical metaphysics of object and property (or substance and attribute), in favour of a conception of objects as processes, where the latter consist of nothing more than properties. He is thus led to construe subjects of experience as nothing more than collections of suitably unified conscious states. He does not 9 spell it out explicitly, but I take it that (part of) his thinking is that once liberated from the confines of a traditional substance, one of the main constraints on the compounding of conscious states is no more. The second move is made explicit, in the course of a complex discussion of one of his own epistemic theses, namely that so far as experience is concerned, ‘the having is the knowing’. Strawson distinguishes a stronger and weaker version of this doctrine (252), and endorses only the weaker: The Full Revelation Thesis: In the case of any particular experience, I am acquainted with the whole essential nature of the experience just in having it. The Partial Revelation Thesis: In the case of any particular experience, I am acquainted with the essential nature of the experience in certain respects, at least, just in having it. If experiences can only reveal a part of their true natures to their subjects – if experiences can have partially concealed natures – then the Combination Problem loses a good deal of its bite. Given Partial Revelation, the fact that my current experience does not seem (to me) to be composed of trillions of smaller experiences is perfectly compatible with its being composite in precisely this way. Unfortunately for the panpsychist, while the move to Partial Revelation helps with some problems, it also creates a now-familiar tension. If some significant features of experience are concealed from us, might it not be that these features make it possible for phenomenal consciousness to emerge from nonphenomenal ingredients? 3. From Descartes to Spinoza Strawson’s Reply goes well beyond the responses to particular lines of criticism to which I have given brief mention thus far. Over the course of an illuminating and invigorating hundred-page essay – Strawson’s prose is turbo-charged throughout – he sets out to clarify what the real issues are, as he sees them. In an attempt to establish a ‘Basic Framework’ for future discussion he constructs a list of some 41 theses (37 metaphysical, 4 epistemological); some familiar claims about the nature of physical reality and its relationship with the experiential domain are to be found here, along with a good many that are good deal less familiar. But this is by no means all: a substantial chunk of the Reply is historical. Strawson is 10 intent on demonstrating not only that the issues he is engaging with are by no means new, but that the general level of discussion on these matters was a good deal higher when conducted by Descartes, Locke, Leibniz and Spinoza than it has been in contemporary philosophy. On the historical front most space is devoted to ‘the magnificent, contumacious Descartes’ who, Strawson claims, remains the best and deepest thinker on the mind-body problem, the philosopher from whom we still have most to learn. Readers unpersuaded by Strawson’s influential ‘realistic’ taken on Hume on causation may have a ‘Oh no, not again …’ feeling here. Inspired by Desmond Clarke (2003), Strawson argues that the traditional textbook interpretation of Descartes is mistaken in several respects.3 First of all, Descartes wasn’t a substance dualist, at least in the contemporary sense of the term. For him the term ‘substance’ serves as a mere placeholder; he regarded the distinction between object and property to be a merely conceptual distinction, rather than a real one. He did think there are two kinds of property – or better, that there is ‘experiential being’ and ‘non-experiential being’ – but having adopted the view that there is no real distinction between a substance and its properties, his dualism must be of the bundle-variety. This makes for an interesting conception of the self or subject: there is, for Descartes, no real distinction between (a) the concrete existence of the attribute of thinking and (b) the concrete existence of thinking substance. His root – radical – idea about the nature of the subject of experience or soul is that it is somehow wholly and literally constituted of experience, i.e. of conscious experiencing: that is what res cogitans – a soul – is. Strawson goes on to argue that an alert reader of his correspondence will find grounds for concluding that Descartes may even have been committed to (or at least tempted by) a position similar to real physicalism – if so, he clearly wasn’t the dualist he is commonly assumed to be. There is abundant evidence that Descartes was very much aware of a very contemporary-sounding objection to dualism: namely, that we are ignorant of the true nature of matter, and so not in a position to rule out the possibility that it possesses a mental aspect or component. There is, of course, plenty of textual evidence that points in the opposite direction, but as Strawson points out, we also know that Descartes was cautious, and prone to concealing his true beliefs when these might provoke (possibly And also Yablo (1990); Strawson does say that he may have gone slightly further than either in this regard. 3 11 dangerous) public controversy. Above all, ‘what one has to do is feel one’s way into the intellectual heart of this man who went to the butcher’s for brains when he wanted to understand the mind’ (215), and then ask oneself which interpretation has the ring of truth. Whether Strawson’s interpretation of Descartes is correct is an issue for Cartesian scholars to decide, but it certainly makes for interesting reading. As for the Basic Framework and its 41 distinctions and theses, it does (perhaps not surprisingly) allow Strawson to refine and clarify the metaphysical position he wants to defend. Having come around to the view – shared by several commentators – that his use of ‘physicalism’ (even when prefixed by ‘real’) may be doing more harm than good, he eventually settles on the following statement of his position: Equal-Status Fundamental-Duality Monism [ESFD]: Reality is substantially single. All reality is experiential and non-experiential. Experiential and non-experiential being exist in such a way that neither can be said to be based in or realized by or in any way asymmetrically dependent on the other (241) This formulation certainly makes it clear what Strawsonian panpsychism involves and requires. It answers the criticism (forcefully made by Macpherson) that his position has many of the features of orthodox property dualism. Also on plain view is the main problem confronting ESFD-monism: how can a single mode of being combine such diverse features? How can one sort of stuff be both experiential and non-experiential? Strawson gives credit to Descartes for being the first to appreciate the seriousness of this difficulty: it is what led him to espouse dualism (if he in fact did, ultimately). But for all that ESFD-monism may seem untenable, Strawson finds consolation in the fact at least one other philosopher – a philosopher whose brilliance is beyond question – certainly espoused something very much akin to it: Spinoza held that ‘experiential being and non-experiential being … are indeed in some metaphysically immoveable sense identical, but that maintaining this is compatible with maintaining some sort of real fundamental duality’ (242). That said, Strawson concedes that even Spinoza failed to make it fully clear how reality could be like this, and so further work is required. But even if the solution remains beyond our grasp, there is a further consoling thought: there is plenty of evidence in both science and philosophy ‘that many of our ways of thinking of reality are quite hopelessly inadequate to reality as it is in itself’ (242). 12 Strawson suggests ESFD-monism is what ‘many people really want, even though they are likely to deny it’ (241). The second claim may well be true, but I have doubts about the first. Although most people are certainly of the view that both experiential and non-experiential modes of being are to be found in our universe, surely most people also believe that large tracts of our universe are entirely non-experiential in nature, with experience being confined to only small portions (e.g., animal brains, or immaterial souls). For those in this camp it would come as a surprise to be told that each and every part of the universe – down to the smallest sub-atomic particle – possesses both experiential and nonexperiential aspects. Many people find it very natural to think physical world has a dark (non-experiential) aspect, it is by no means evident that this idea will retain its appeal if the only way of retaining it is to ascribe a light (experiential) side to the entirety of the physical world. This point aside, it should be noted that Strawson’s stance is a cautious one. ESFD-monism may be the best we can hope for, but we cannot (at this point in time) be sure it is true, or ultimately intelligible. If it should turn out not to be acceptable, given the assumptions currently in play (e.g. monism, no brute emergence), so far as he can see there is only one other option open to us: pure panpsychism. If the non-experiential cannot co-exist (ESFD-style) with the experiential, since we cannot deny the existence of the latter, we must deny the existence of the former, and hold that concrete reality is wholly experiential. In explicit recognition that this is may ultimately prove to be the more plausible position, from this point on ESFD-monism is largely sidelined, and for most of the remaining sections of the Reply Strawson assumes pure panpsychism to be true. Some of the ground covered in these sections is already familiar – it is here that he discusses the Combination Problem, and takes the strategic decision to reject the Full Revelation thesis – but one final aspect has yet to be mentioned. The pure panpsychism Strawson want to defend and explore is of the ‘naturalistic’ variety: he is still assuming that the world is composed of small elementary particles (so as to ensure maximum compatibility with current physics), but he also wants to make room for causation, construed realistically (i.e., as more than mere behavioural regularities). The move to Partial Revelation is of assistance here: that our conscious states are composed of causally active constituents is not something that is evident in our experience, but this is not a problem if our experiences have features that are not discernible by us. Making this move brings benefits on several fronts. First, it is easier to regard experiences as genuine things if they possess causal powers. Second, we now have available something akin to an external world even though reality is entirely experiential in 13 nature, for when one ‘experiencing affects another …. the second obviously will not have access to the from-the-inside nature of the first in the way in which only the first can … In this sense experiential realities may be said to function as nonexperiential but experience-causing realities for other experiential realities’ (261). Last, but certainly not least, viewing experiences in this way gives us ‘a first intimation of how panpsychist monism can allow some sort of fundamental and all-pervasive duality to existence (a glimmering of the possibility that ESFDmonism may be intelligible after all’ (256). Strawson evidently takes pure panpsychism to be a way in which (real) physicalism could be true, and this may sound odd. If the universe of the pure panpsychist contains nothing that is not experiential in nature, isn’t pure panpsychism simply a form of idealism? In one sense it is, but it is also a form of idealism in which there is an external reality which, in a sense, is recognizably physical: the elementary particles may be experiential in nature, but they are distributed through a space of three (or more) dimensions, and their behaviour conforms to the laws of fundamental physics. This is precisely the conception of physical reality to which the growing band of followers of the Russell-Eddington line subscribe, and with which Strawson has considerable sympathy. According to Russell and Eddington (but also Clifford, Lockwood and others), physics only provides us with formal or structural descriptions, it has nothing to say about the intrinsic nature of the physical; if we assume, as seems plausible, that the physical world does have an intrinsic nature of some kind, the latter might well be experiential – this is certainly the most economical hypothesis, given that we know beyond any doubt that intrinsic properties of this sort do exist. There is much that is plausible here, but this phenomenalized physicalism, as one might call it, also brings difficulties of its own. Are the causal laws to which elementary (phenomenalized) physical things conform necessary or contingent? It is not obvious how they could be necessary. To illustrate, suppose that in the actual world some elementary particles are (phenomenal) red, others are (phenomenal) blue, and particles of these kinds attract one another. Might it not be otherwise? Is there a possible world where intrinsically indistinguishable red and blue particles repel one another? It is difficult to see why there shouldn’t be such a world: what is it about these colour qualities which entails that instances of them can only attract one another? There seems to be no such behaviourguaranteeing feature. But if we conclude that the laws governing the elementary particulars are merely contingent a difficulty looms on the horizon. The elementary particulars which exist in our world also exist in worlds where the laws governing them are very different. In some worlds the laws restrict the 14 particles to just one spatial dimension; in others these same particles are distributed through million-dimensional space – yet further worlds finds the particles behaving in all manner of strange (to us) ways. Since many of these worlds will bear any resemblance to our world, it is difficult to see why we should regard them as physical at all. But if this is right, the particles which make up our world are themselves at best only contingently physical: as it happens, in our world they are disporting themselves in a physical way, but in a multitude of other worlds they are behaving very differently. It is starting to look as though our world is not fundamentally physical at all – and indeed, on a number of occasions John Foster has appealed to considerations of just this sort in arguing that physicalism – construed as the claim that reality is essentially physical – is an incoherent doctrine.4 Perhaps aware of this threat, Strawson immunizes himself against it: he holds that all things – and hence basic experiential particulars – possess all their causal powers essentially (262). He willingly grants that it is not transparently obvious why certain phenomenal qualities essentially possess certain causal powers, but here once again his rejection of Full Revelation comes to the rescue: experiences possess some features which are not revealed in the simple having of them. But while this certainly makes room for the required causal essentialism, the latter remains problematic. It is very difficult to see why any phenomenal property should necessarily possess the causal powers that it does possess. So much so that we are, I think, entitled to be sceptical of this essentialist doctrine, at least in the absence of any positive arguments as to how it could be true – arguments which Strawson does not (here) provide. 4. Unity and Transitivity To bring matters to a close I want to take a brief look at a topic that is largely overlooked by Strawson and his commentators, but has some relevance to the themes under discussion. In his contribution Lycan writes: Suppose I am looking out of my kitchen window, and simultaneously seeing a rabbit in my back yard, hearing my wife’s cat yowling that he wants to behead the rabbit, feeling the touch of my fingertips on a bottle of salad dressing, smelling the spaghetti sauce in the pot, suffering an ache in my right shoulder, and imagining in anticipation a very tall frosty beer. In 4 Most recently Foster (2008); see also Robinson (1985). 15 what way could such a mental aggregate consist of or be determined by or otherwise ‘arise from’ a swarm of smaller mentations? (69) Lycan’s concern here is the Combination Problem, but he nicely brings to our attention an important, but easily overlooked, feature of our ordinary streams of consciousness. At any one time, our overall consciousness typically comprises a collection – or aggregate – of different experiences; these experiences do not occur separately, or in complete isolation from one another, rather they are experienced together – or, as it is commonly put, they are co-conscious. Lycan’s visual experience of the rabbit is co-conscious with his hearing of the cat’s yowling, and both these are co-conscious with his various bodily sensations, and the imagining of the tall frosty beer. Generally speaking, each of our experiences at any one time is co-conscious with all our other experiences. Indeed, this distinctive mode of unity runs further and deeper than this. Co-consciousness not only connects experiences of different sorts, it also holds within experiences: as Lycan looks out onto his garden, all the different parts of his visual experience are themselves coconscious. This relationship of co-consciousness is in one sense elusive, for the relationship itself does not have any introspectively discernible features. When a visual experience is co-conscious with an auditory experience, we are not aware of any additional experiential element joining the two – there is no discernible phenomenal glue, as it were – we are simply aware of the auditory and visual experiences together. From a purely phenomenological perspective, coconsciousness just is this ‘experienced togetherness’. But since we are all very familiar with what it is like for experiences (or their contents) to be experienced together in this way, in one sense at least there is nothing in the least mysterious about the relationship in question.5 Strawson is himself fully aware of the distinctive sort of unity which exists within consciousness. Elsewhere he writes ‘it seems that there is, in nature, as far as we know it, no higher grade of physical unity than the unity of the mental subject present and alive in what James calls the “indecomposable” unity of a conscious thought.’ (1999: 128) What is less clear is whether he appreciates a difficulty this mode of unity makes for his preferred form of panpsychism, ESFDmonism. The main difficulty confronting the latter is whether such (seemingly) different and distinct modes of being as the experiential and the non-experiential can really be aspects of just one mode of being. To put it another way, can the experiential and non-experiential be unified in a way which makes it plausible or 5 See Dainton (2006, chapters 1-4; 2008 ch.3) for more on this. 16 possible to hold they are parts or aspects of a single thing? A solution (of a sort) would be available if we could appeal to the doctrine of bare particulars, for there is no obvious reason why an entity of this sort could not possess – and thereby unify – experiential and non-experiential properties: after all, being themselves devoid of properties, bare particulars are neither experiential nor non-experiential in nature. But Strawson has firmly (and probably rightly) rejected this doctrine in favour of a bundle-theory: ‘the best thing to say, given our existing terms, is that objects are (just) concrete instantiations of properties’ (195).6 From this perspective, the question of which property-instantiations constitute objects depends on which properties are bundled together, and how. The trouble now, for the ESFD-monist, is resisting a strong pull in a dualistic direction. If we focus our attention solely on the experiential realm we have a reasonably clear picture of the form the bundling-into-objects takes: experiences are bound into unified wholes by the relationship of coconsciousness. The situation is a good deal less transparent at the nonexperiential level, but we have some idea of the sort of story science is likely to tell: elementary physical objects existing in spatial relations, being pulled together – and pushed apart – by various forces. So we have two quite different sorts of item (phenomenal v. non-phenomenal) and two quite different bundling relations (co-consciousness v. physical forces and relations). It looks very much like we have the makings of two distinct ontological realms. Indeed, if we further add to the mix causal interactions between the experiential and non-experiential, as Strawson very much wants to do, we end up with something not dissimilar from the orthodox Cartesian metaphysics! To avoid this fate it is obvious what we need: a unifying, bundling-relation which can bridge the gap between the experiential and non-experiential. But it is not obvious what such a relation would be like, or how it could do what is required. Clearly, co-consciousness isn’t capable of bridging the divide, since the relationship of experienced togetherness only holds between experiences. As for causation, even on the assumption that there can be causal relations between the experiential and non-experiential, it is unclear how being so related could bring about the sort of deep unity required by ESFD-monism: after all, most causes are distinct from their effects. Does this mean there couldn’t possibly be such a relation? Perhaps not, there are further alternatives. Perhaps most plausibly, the monist could appeal to a relationship of co-instantiation, and maintain that, in As the qualification here suggests, calling Strawson a bundle-theorist isn’t quite right, for he thinks our ordinary concepts of ‘object’ and ‘property’ probably aren’t suited for capturing how things really are – he prefers ‘modes of existence’ to ‘property’ – but as far as I can see, it’s not far wrong. 6 17 virtue of its complete generality (and neutrality), this relationship is as capable of binding experiential and non-experiential modes of being as it is of binding properties of any other sort. But while some panpsychists might avail themselves of this option, it is unlikely to appeal to Strawson. How does this bare coinstantiation relation differ from the bare particulars he vehemently rejects? Even if a difference could be found, a pure co-instantiation relation is as devoid of phenomenal and material characteristics as any bare particular, and so not something Strawsonian real physicalists will happily embrace.7 Even if it is embraced we are left with a problem: how does supposing experiential and nonexperiential properties are bound together in this sort of way help us to understand how they can be aspects of a single mode of reality? Now of course Strawson might well say that the issue of what unifies the experiential and nonexperiential simply doesn’t arise, for if ESFD-monism is true, they aren’t truly distinct in the first place. But while this may look to be a promising line to take, it is also an unstable one. Strawson also concedes (as he must) that there is a profound duality within ESFD-reality, and so the question of what unifies the dual elements will not easily be made to go away.8 Let us set ESFD-monism aside and move on to a different but related issue. It may not be immediately obvious, but the co-consciousness relationship could prove to be extremely useful to the panpsychist. But it could also be extremely dangerous, even fatal. Let me explain. The potential benefits – as well as the potential problems – depend on whether or not co-consciousness is a transitive relationship. Returning to Lycan’s example, in actual fact his visual experience of the rabbit is co-conscious with both his auditory experience of the cat’s yowling and his olfactory experience of the spaghetti sauce – for (we can plausibly suppose) each and every part of his experience at this time is co-conscious with every other part. But could it have been otherwise? Might his visual experience have been co-conscious with his Here Nagel’s remark about panpsychism bearing ‘the faintly sickening odor of something put together in the metaphysical laboratory’ (1986: 49) may come to mind. 8 One final thought on this issue. Properties such as mass and speed are scalar, involving as they do just one quantity or variable; other properties, such as momentum and velocity, involve two quantities or variables, and so are vectors. From this vantage point the ESFD-monist is claiming that the intrinsic nature of reality is fundamentally vector-like: it consists of two components which are by their nature inseparable. But while construing matters in this way helps situate ESFD-monism in the broader metaphysical landscape, it does not help much with the real difficulty: understanding how the experiential and non-experiential can be aspects of a single mode of being. 7 18 auditory experience, and the latter co-conscious with his olfactory experience, without his visual and olfactory experiences being co-conscious? This is hard to imagine, very hard. The fact that most of us find it impossible to conceive of a state of consciousness which is only partially unified lends considerable weight to the contention that co-consciousness is a transitive relation: that for any three experiences e1, e2 and e3 at a time t, if e1 is co-conscious with e2, and e2 is coconscious with e3, then e1 and e3 will also be co-conscious. This synchronic transitivity thesis is very plausible – it goes hand-in-hand with the notion (which many also find plausible) that a subject’s overall consciousness is necessarily unified, at any given time – but it can also lead to trouble for the panpsychist. Sitting comfortably in its hard skull, surrounded by liquid and soft tissues, the human brain looks to be a reasonably sharply delineated object. The situation would look quite different if we could shrink ourselves down to the size of elementary physical particles – quarks, photons, gluons, strings, loops etc. At this very small scale there would be a high degree of continuity: neurons, blood and bone may look very different, but they are each entirely composed of the same elementary ingredients. It could very well be that if we could see down to the quark- (or string-) scale, the entire planet would seem to be a largely homogeneous swarming of elementary particles, with little or no differences to be discerned between brain and bone, or sea, earth or air. Indeed, if – as contemporary physics suggests – even (seemingly) empty space is densely packed with short-lived virtual particles, this homogeneity could extend throughout the entire universe. Why might any of this prove problematic for the panpsychist? Well, consider a chain of particles, P1—P2—P3—P4—P5—P6, where each is directly physically bonded to its immediate neighbour. Strawson maintains that all causal relations – and hence particle-particle interactions (and bonds) – have an experiential aspect. Let’s suppose he is right about that. How might the physical connection between P1 and P2 be manifest on the experiential level? A natural answer – the only answer which springs to mind – is that P1 and P2 are experientially unified: they are experienced together. Or to put it another way, they are co-conscious. Hence the difficulty. If co-conscious is transitive, then P1 will not only also be co-conscious with P2, it will also be co-conscious with P3, P4, P5 and P6; indeed, since each member of this collection of particles-cumexperiences will be co-conscious with each of the others, the collection will comprise a maximally unified conscious state. While this in itself may not be a problem, given the depth of physical interconnectedness – i.e., the sheer number of physical interactions and bonds to be found in the micro-world – the 19 ‘contagion’ (as it were) is difficult to contain. If every particle composing the planet Earth is linked (directly or indirectly) to every other by a chain of physical connections (or interactions) – a by no means implausible assumption – then the entire planet will consist of a single fully unified consciousness. Since it is by no means inconceivable that the same applies to every particle in the universe, the transitivity of co-consciousness renders absolute idealism – the view that the cosmos itself is a single (giant) consciousness – a live option. It also leads to a result which is obviously very implausible, for the experiences of distinct human subjects – you and me, for instance – are clearly not mutually co-conscious in this manner. Of course there is much that is very speculative here, but it is the sort of speculation which Strawson thinks we should take seriously. The catastrophic conclusion is easy to avoid. The panpsychist can simply deny that micro-physical unity goes hand-in-hand with micro-experiential unity. Alternatively, and in a more constructive vein, they might want to reject the assumption that coconsciousness is a transitive relation. While it is very natural to think that synchronic co-consciousness is invariably transitive, this may in large part be due to the fact that our overall states of consciousness at any given moment generally are fully unified. But it could easily be a mistake to suppose that the character and form of our ordinary everyday experience is a reliable guide to how experience can be. There are also well-known pathological cases which can be interpreted in terms of a partially unified consciousness: to mention just one example, Michael Lockwood has argued that split-brain cases can plausibly be interpreted in this way (1989: ch.6). It is certainly possible that these cases are less than conclusive, and that the difficulty we have in envisaging a partially unified state of consciousness reflects an insight we have into the real nature of consciousness and phenomenal unity (Dainton 2006: ch.4; 2008: §8.6). But this line of argument will itself be less than persuasive for those who, like Strawson, are prepared to accept that experience can have characteristics which are not evident to their subjects: once again the rejection of Full Revelation proves useful. Holding co-consciousness to be non-transitive doesn’t just halt the slide towards single-subject absolute idealism, it can also assist with the panpsychist’s Combination Problem. How is it possible for micro-experiences (and/or microsubjects) to combine or sum to form more complex ensembles? If subjects are entirely separate and discrete, and each experience necessarily belongs to just one subject, the required combinations seem impossible. However, the situation changes significantly if co-consciousness is non-transitive. Consider first the 20 simplest instance of a partially unified conscious state, one comprising three parts, p1, p2, p3, where p1 is co-conscious with p2, and the latter is co-conscious with p3, but where p1 and p3 are not co-conscious. To make matters a little more concrete, let’s start by supposing that p1, p2 and p3 are expanses of phenomenal colour, organized in the manner shown in Figure 1, where the circles indicate contents which are mutually co-conscious, and the larger experiences E1 and E2 are composed of [p1-p2] and [p2-p3] respectively. p1 E1 p2 p3 E2 Figure 1 Of interest here is the fact that a single token experience can be a full-fledged part of a fully unified state of consciousness (in the way p2 is part of E1) but this does not prevent this same token being a full-fledged part of a distinct fully unified conscious state (p2 is also part of E2). Of course ‘distinct’ here means ‘nonidentical’ rather than ‘wholly distinct’ – E1 and E2 partly overlap – but this is already a significant gain. One of the deepest and most puzzling aspects of the Combination Problem is how a single experience can belong to more than one total state of consciousness. We see from this simple example that this is possible, provided co-consciousness can be non-transitive. A question immediately arises as to how we should interpret this situation: do p1, p2 and p3 all belong to just one subject, or does each belong to a different subject (making three subjects in total), or are there just two subjects here, one for E1 and another for E2? Looked at in one way, the single subject option can seem a very natural one. Since p1 and p2 are experienced together it is natural to think they have a single subject; since p2 and p3 are experienced together they must belong to the same subject, so it seems we are led to the conclusion that all three 21 experiences have a subject, even though p1 and p3 are only indirectly co-conscious. While this may seem reasonably appealing in this simple case, it is less so in more complex cases, e.g. where p1 and pn are connected (but also separated) by a chain of a thousand partially overlapping total states of consciousness. There is further and more immediate consideration: it is also very natural to suppose that the consciousness of a single subject is fully unified, and the experiential ensemble comprising E1 and E2 is most definitely not fully unified. So should we go for the two-subject option, and regard each of E1 and E2 as a distinct subject? In cases where the region of overlap is very small, that may well be the most plausible interpretation. Just suppose E1 is your current state of consciousness, E2 is mine, and p1 is a tiny pain sensation that is common to us both (thanks to some experimental neural surgery our brains have been connected). In yet other cases, e.g., when all three experiences are of much the same kind and character, the three-subject interpretation may be the most plausible. This metaphysical option, intriguingly, allows experiencing subjects to be wholly included in other subjects as parts: to illustrate, suppose p2 has its own subject, but so too does E1. This state of affairs may well seem odd, but arguably the panpsychist needs precisely this possibility. Of course, faced with this proliferation of possibilities some may be inclined to abandon all talk of subjects in such cases. But this may be an overreaction, and it is certainly not an option for those who are committed to the ‘no experience without an experiencer’ principle, and who also believe – with Strawson – that there is no real distinction between conscious states and subjects. One final point. McGinn notes the way in which a vast variety of large and medium sized physical objects can be constructed from a small range of elementary physical ingredients, and comments: The reason for this fecundity is that there are so many possibilities of combination of simpler elements, so we can get a lot of different things by spatially arranging a smallish number of physical primitives. But there is no analogous notion of combination for qualia – there is no analogue for spatial arrangement (you can’t put qualia end-to-end). We cannot therefore envisage a small number of experiential primitives yielding a rich variety of phenomenologies; we have to postulate richness all the way down. (96) Once we drop the assumption that co-consciousness is transitive, the claim that there is no spatial analogue for qualia looks to be highly questionable, as Figure 2 illustrates: 22 Figure 2 If we suppose that the circles in Figure 2 represent expanses of phenomenal colour, McGinn’s claim that there is no spatial analogue for qualia is obviously mistaken. But suppose, instead, that each circle represents an auditory-content; even if these auditory contents lacks much by way of intrinsic spatial extension, the overlap structure is functionally equivalent to a spatially extended structure: are there not paths between locations and analogues of distance and direction? I stress again that I am by no means sure structures of this sort are in fact possible, but if they are, there may be the beginnings of an answer to the question of how macro-experientiality emerges from micro-experientiality. Alas, the Combination Problem is multi-faceted. Partial overlap is of no obvious assistance with the ‘derivation problem’: explaining how a small family of experiential primitives give rise to the diversity of very different phenomenal qualities which figure in our experience – how can colours, tastes, smells emerge from the narrow range of simple qualities possessed by elementary particles? But when dealing 23 with a doctrine as peculiar, puzzling and seemingly hopeless as panpsychism, even small measures of progress are worth having. Barry Dainton -------------------- References Clarke, Desmond (2003) Descartes’ Theory of Mind. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Bedau, M. & Humphreys, P., eds, (2008) Emergence. Cambridge MA: MIT Dainton, B. (2006) Stream of Consciousness. London: Routledge. Dainton B. (2008) The Phenomenal Self. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Foster, J. (2008) A World for Us. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Lockwood, M. (1989) Mind, Brain and Quantum. Blackwell: Oxford. Laughlin, Robert B. (2005) A Different World: Reinventing Physics from the Bottom Down. Basic Books: New York. Laughlin, Robert B & Pines, David (2000) ‘The Theory of Everything’ in Bedau and Humphreys. McLaughlin, B. (1990) ‘The Rise and Fall of British Emergentism’ in Bedau and Humphreys. Nagel, T. (1979) ‘Panpsychism’, in Mortal Questions, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Nagel, T. (1986) The View from Nowhere. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Noble, D. (2006) The Music of Life. Oxford: Oxford University Press. 24 Robinson, H. (1985) ‘The General Form of the Argument for Berkeleian Idealism’, in Foster & Robinson (eds), Essays on Berkeley, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 163-86. Strawson, G. (1999) ‘The Self and the Sesmet’, Journal of Consciousness Studies 6: 99-135. Yablo, S. (1990) ‘The real distinction between mind and body’ Canadian Journal of Philosophy, 16: 149-201 25