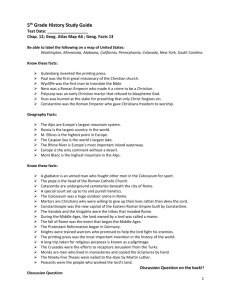

Christianity During the First Millennium.

advertisement

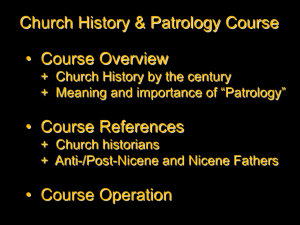

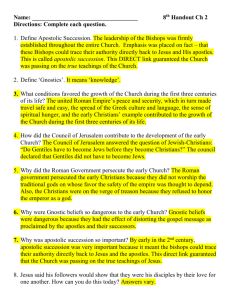

Christianity During the First Millennium Christianity during the first thousand years of its existence was markedly different from that familiar today. Here are some of its distinctive features. 1. The Authority of Tradition Most Christians today regard the Bible as the ultimate authority for their faith. Early Christians did not share this assumption, for the simple reason that the Bible as we know it did not yet exist. The list of canonical writings - those today constituting the Bible - was not fixed until the fourth century. Prior to that time there was a core of books with unquestioned authority (including the Old Testament, the Gospels, the letters of St. Paul and St. John, and I Peter) surrounded by a looser assortment of works whose authority was recognized by some local churches but not by others. Of this latter group, the works ultimately judged canonical include Hebrews, James, II Peter, Jude, and Revelation, as well as the late Jewish writings sometimes called the “Apocrypha.” (The Apocrypha were later excluded by Protestants during the Reformation.) Those judged non-canonical included the Didache, the Epistle of Barnabas, the Shepherd of Hermas, I and II Clement, and the Apocalypse of Peter. On what grounds were these decisions made? One important criterion was whether the content of a given book was consistent with accepted Christian teaching. This implies, of course, that there was a standard of accepted Christian teaching already in existence. In part this standard was constituted by "Scripture" as it was understood at that time. (In the first century the term "Scripture" was used solely for the Hebrew scriptures, i.e., the Old Testament. Later it came to include the canonical Christian works, whatever those were judged to be.) The standard also included the teaching personally conveyed by the apostles. There are several references in the New Testament to the importance and authority of such apostolic tradition (I Cor. 11:2, II Thess. 2:15, 3:6, Jude 3). As these passages indicate, the apostolic tradition was transmitted orally as well as in writing. It included some aspects of which there is today no written record. These were preserved in the daily practice and teaching of the Church. Some of them can be inferred from the writings of the “Apostolic Fathers,” the leaders of the generation immediately following the apostles. More important than the specific content of these teachings, however, was the general principle that it is the teaching and practice of the Church, rather than any written work, that are ultimately decisive for the Christian faith. Even Scripture itself was regarded as simply one aspect - though obviously a very important one - of Holy Tradition. 2. Bishops Whether the early Church included bishops and priests has been a controversial issue ever since the Reformation. Generally speaking, Catholics say it did and Protestants say it did not. Part of the difficulty arises from the ambiguity of the terms involved. The New Testament uses "bishop" (episkopos, overseer) interchangeably with "pastor," "steward," and "elder" (presbyter, a word later meaning "priest") (Acts 20:17, 28, Phil. 1:1, I Tim. 3:1-7, Titus 1:5-7, I Peter 5:1-4). It appears from these passages that there was usually more than one such leader in a local church, although one might enjoy special eminence. The institution of monoepiscopacy - one bishop per city - is first clearly attested in the letters of one of the Apostolic Fathers, St. Ignatius of Antioch, early in the second century. It soon became the norm at all churches. The basis for the authority of bishops is the idea of apostolic succession. The New Testament states that the apostles appointed leaders in the churches they founded (Acts 11:22-26, 14:23, II Tim. 2:1-2, Titus 1:5). I Clement, written about 95 A.D., makes it clear that the offices thus created - those of bishop and deacon - were regarded as permanent institutions responsible for preserving the teaching of the apostles and endowed with their authority (ch. 42-44). Late in the second century, in the face of the Gnostic heresy, the influential work of Irenaeus of Lyons emphasized that one way to distinguish orthodoxy from heresy is to check whether a given teaching is in conformity with that of the successors to the apostles (Against Heresies III.3). Since the bishops were the successors to the apostles, they were also regarded as possessing the power of "binding and loosing" bestowed on the apostles by Christ (Mat. 16:19, John 20:22-23). Just as the apostles met in council to settle a disputed issue (Acts 15), bishops met in council to regulate the life of the Church. When such a council involved bishops from only a particular area it was called a “synod.” Later, after the conversion of Constantine, the bishops of the entire Empire began to meet as a body. The first such “Ecumenical Council” was the Council of Nicaea convened by Constantine in 325 A.D. to resolve the Arian heresy. Others included the Council of Constantinople (381), the Council of Ephesus (431), and the Council of Chalcedon (451). These were summoned to deal with various heresies relating to the Trinity and Incarnation, but they also legislated on matters of church discipline and canon law. There were limitations to the authority of the bishops. Since the bishops were the guardians of apostolic tradition, they were supposed only to clarify existing teaching rather than promulgate new doctrine. This meant that the Church as a whole had the implicit right to judge whether a council had acted correctly. Once the Emperor became involved in church politics, it was not uncommon for a council to meet and make decisions under political pressure that were later rejected by the Church. These were "robber" or "false" councils, and bishops who had supported them were often deposed. 3. Liturgical worship The nature of worship in the early Church is another controversial topic. The crucial question is how much continuity there was between early Christian worship and that of the Jews. According to the Encyclopedia of Early Christianity, "The earliest Christian community of Jerusalem [both] participated in Jewish worship and followed the custom of other sectarian groups in holding private meetings . . . The definitive break with official Judaism, within three decades, and the establishment of the Christian churches in new cultural contexts, occasioned significant changes in the shape of Christian worship. But the structure of synagogue services was observed: reading and exposition of scripture within the context of prayer and confession. Jewish psalms, hymns, songs, and prayers were adapted. Also, the Jewish practice of morning and evening prayers was retained." The Encyclopedia also notes that the descriptions of heavenly worship in Hebrews 9 and Revelation 4-5 imply a strong sense of continuity with Jewish worship in the Temple. Worship in the Temple, of course, was highly liturgical, involving priests, vestments, chant, incense, a liturgical calendar, and a form of ritual that was regarded as divinely sanctioned and immune from revision. When did these elements appear in Christian worship? The answer appears to be gradually during the second and third centuries. Fragments of early Christian liturgy are contained in writings of the Church Fathers, especially the I Apology of Justin Martyr (c. 150) and the Apostolic Traditions of Hippolytus (c. 220). No attempt was made at standardization, however, so various liturgies developed in various local churches. After the conversion of Constantine, the Church moved gradually to restrict innovation and achieve uniformity. But there remained a number of distinct eucharistic liturgies. (“Eucharist,” thanksgiving, was the early name for Communion or the Lord’s Supper.) The most important are the Liturgy of St. John Chrysostom developed in the East and the Roman rite developed in the West. The former is still practiced in Eastern Orthodox churches. The latter was practiced in the Roman Catholic Church prior to Vatican II, and is still occasionally celebrated as the "Latin" or "Tridentine" mass. 4. The Real Presence The doctrine of the Real Presence is the belief that the body and blood of Christ are truly present at the Eucharist. Its biblical basis is the statements of Jesus at the Last Supper ("this is my body" and "this is my blood") and Jesus’ teaching in John 6:48-65 that in order to receive eternal life one must eat his flesh and drink his blood. Precisely what "truly present" means is a difficult question. Nonetheless, some form of belief in the Real Presence was unanimous in the early Church; no one ever asserted that the bread and wine offered at the Eucharist are merely symbols. Since belief that Christ is bodily present naturally prompts a sense of awe and reverence, the doctrine of the Real Presence further encouraged the development of liturgical worship. 5. Veneration of Saints and Their Relics Another impetus in the development of liturgical worship was the veneration of saints. It began with the veneration of martyrs. This, in turn, developed in two stages: first, beginning in the second century, the preservation of their relics and annual celebration of the date of martyrdom, as illustrated in The Martyrdom of Polycarp; then, beginning in the third century, prayer to the departed martyrs to ask for their intercession in heaven. The latter was viewed as an extension of the ordinary practice of asking for the prayers of one's fellow Christians on earth. (If it is right to ask a living Christian for prayer, why not ask the same of one already in heaven?) Later, after the end of persecution, these practices were extended to others who had lived notably holy lives. Eventually the practice of declaring someone a "saint" was more or less codified, although even today it begins with local and spontaneous devotion by those who knew the departed person. As regards relics, the Bible attests that the supernatural power present in a person can be transferred to his bones or possessions (II Kings 2:14, 13:21, Matt. 9:20-22, Acts 5:15, 19:12). Thus, given the veneration of the martyrs, it is not surprising that their relics should also be venerated and regarded as sources of healing. As the story in Matthew 9 illustrates, such healing is not "magic" and cannot occur apart from faith. Nonetheless, in the Middle Ages saints’ relics were often regarded as possessing virtually magical powers, and the traffic in relics (and theft of relics) became a major activity. 6. Veneration of Mary Once the number of saints was extended to other holy persons besides martyrs, it was natural to include prominent figures in the Bible. But Mary is a special case. She has an importance in theology far beyond that of any saint, and eventually the devotion shown to her came to exceed that shown to anyone other than her son. In the New Testament the most important passage about Mary is the “Magnificat,” Luke 1:46-55. (It is so-called because in Latin it begins magnificat, “magnifies.”) Her significance was further emphasized in the second century by Church Fathers like Justin Martyr and Irenaeus. Elaborating on the notion of Christ as the second Adam (Romans 5), they interpreted Mary as a second Eve. Like Eve, she was faced with a choice of whether to rebel or submit to God's will; unlike Eve, she submitted, and as a result salvation came to the world. As these writers saw it, her very body was holy because it had contained God. Indeed, she was more holy than the Holy of Holies in the Temple, for whereas it had contained only the Ark of the Covenant, she had contained God in the flesh. Hence, they inferred, she must have remained a virgin even after giving birth, for no man would have dared to impose himself where God had been. The offering of prayers and veneration to Mary - as distinct from recognition of her theological importance - began in the early fourth century. Some writers were critical of it from the beginning, for they recognized the danger that so unique and important a person might come to be regarded as a goddess. To guard against this, in the East there was a convention that she never be depicted apart from her son. No such convention seems to have existed in the West, and, in general, Marian devotion ultimately took more radical and innovative forms in the West than in the East. 7. Monasticism The Bible mentions several instances where someone seeking spiritual guidance or rejuvenation retires alone to the desert to fast and pray (e.g., I Kings 19, Matt. 4:1-2, Gal. 1:17). About the middle of the third century Christians in scattered locations throughout northern Egypt and Syria began to embrace this pattern as a permanent mode of life. The most famous such early monk was St. Antony the Great, whose Life by St. Athanasius became a pattern for the monastic movement. Some monks lived entirely alone (eremitic monasticism), some in communities governed by an elder (cenobitic monasticism), and some in solitary cells relatively close to one another (semieremitic monasticism). Aside from fasting and prayer, the most distinctive feature of monastic life was the struggle to renounce one's own will. The Sayings of the Fathers is full of stories of elders issuing seemingly pointless commands so that their disciples could learn the habit of unquestioning obedience. By renouncing his own will, a monk sought to achieve a state of humility and freedom from the passions similar to that of the angels; hence the monastic life was also known as the "angelic life." A number of Church Fathers wrote rules for governing monastic communities. The most important in the East was that of St. Basil (fourth century) and in the West that of St. Benedict (early sixth century). Because of the fall of the Roman Empire in the West, western monasticism eventually took on different social functions than in the East. The monasteries were the sole keepers of ancient learning; they were great landowners; and they were convenient repositories for the younger sons of the nobility. In the East they never had to take on these responsibilities. The result was that monasteries in the West took on a more activist role in relation to society at large, whereas those in the East remained closer to the original ascetic and penitential spirit of the Desert Fathers. 8. Fasting Fasting is common throughout the Old Testament, and it is clear that Jesus expected his disciples to fast after his departure (Matt. 9:14-15, cf. Acts 13:1-2, 27:9). The earliest allusion to fasting after the New Testament is in the early second-century document known as the Didache, which states that Christians are to fast on Wednesdays and Fridays. The choice of these days was later understood as commemorating, respectively, the betrayal and crucifixion of Christ. It was also common to fast for one or several days prior to Pascha (Easter), particularly since this was the time when converts were baptised. In the fourth century there came to be more fasts, perhaps in imitation of the ascetics of the desert. The new fasts included fasting before communion and for forty days prior to Pascha (the period now known as Lent). Precisely what constitutes a fast varied with time and place. Eventually it came to be understood as abstaining from all animal products, including meat, fish, milk, cheese, and eggs, along with alcohol. Such a diet is called xerophagy, "dry-eating," because it leaves the body feeling somewhat light and dry, without the heaviness that comes from fatty and oily foods. 9. Confession Another spiritual discipline was confession. Christians are commanded to confess their sins to one another in James 5:16. It is unclear whether the confession is to be private or public and how frequently it is to occur. During the second and third centuries, confession seems to have been limited to the rite of reconciliation, in which one who had committed a notable sin (such as apostasizing during persecution) would submit publicly to the elders. During the fourth and fifth centuries this practice evolved into the private rite of confession to a priest. Just as with fasting, it seems that the ascetics of the desert provided the model. The ascetics would confess not only their sinful actions but even sinful or despondent thoughts to the elder of their community in order to receive guidance and support. The frequency and nature of confession varied considerably with time and place. Today people are most familiar with the confessional, a stall in which the penitent sits and confesses his sins to a priest who remains hidden behind a screen. This was a late medieval innovation. In antiquity and the early Middle Ages the practice was to confess while standing beside the priest and facing a cross or portrait of Christ. 10. The Sign of the Cross Originally the sign of the cross was made by tracing the point of the forefinger across the forehead. This practice is mentioned in documents of the mid-second century. The modern form came into use during the fifth century. It varies slightly between the eastern and western churches: in the East it is made with the two long fingers and thumb, going from forehead to chest to right shoulder to left shoulder; in the West with all the fingers extended, going from forehead to chest to left shoulder to right shoulder. The sign of the Cross is frequently mentioned in lives of the saints as a weapon against demons. 11. The Papacy Since Rome was the capital of the empire, it is not surprising that the bishop of Rome should achieve special prominence.1 Besides its political role, Rome was also the city where Peter and Paul had been martyred and the only bishopric in the West founded by an apostle. Furthermore, during the dogmatic debates of the early centuries the position taken by the bishop of Rome was usually - though not without exception - the one that ultimately prevailed. All of these factors worked together to give the bishop of Rome a special aura of authority. It is important to distinguish the idea of Papal primacy from that of Papal supremacy. All the bishops of the Empire were willing to recognize that the bishop of Rome was, for the reasons mentioned, "first among equals." This primacy of honor was explicitly recognized at the Second Ecumenical Council in 381. The same council, however, asserted that since Constantinople was the "New Rome" the bishop of Constantinople would immediately follow the bishop of Rome in honor. The bishop of Rome rejected this act because it implied that Rome’s primacy was based primarily on its political position. The Fourth Ecumenical Council in 451 went further and listed five patriarchates, each of which was to be the final authority within its own sphere of influence. In order of precedence, they were: Rome, Constantinople, Alexandria, Antioch, and Jerusalem. This system, known as the "Pentarchy," was accepted throughout the East, and it is still regarded by the Eastern Orthodox as setting the fundamental pattern for church government. The bishop of Rome refused to recognize it. The reason is that by this time he claimed, not only a primacy of honor, but jurisdictional supremacy over all the churches. There are sporadic hints of such a claim during the early centuries, but it became clear and consistent only about the middle of the fourth century. That is when the bishop of Rome began referring to Rome as "the apostolic see" and basing his claim to authority on the notion that he is the successor to Peter, the chief of the apostles. These claims were never recognized in the East. In the West they were widely accepted, particularly after the fall of the Empire left the Papacy as virtually the only remaining authority with ties to the ancient world. Disagreement over Papal supremacy eventually led, in 1054, to an open break between the eastern and western churches. Once the western church was freed of its ties to the more conservative East it entered upon a period of rapid innovation. In the fifty years immediately following the schism the Papacy initiated two movements that were recognized by contemporaries as revolutionary: the Gregorian reform, which centralized ecclesiastical authority in Rome, and the Crusades. Other innovations soon followed. Among them were the doctrine of Purgatory, the practice of indulgences, Gothic architecture, scholasticism, the mendicant orders (Franciscans, Dominicans, and Carmelites), the military orders (Hospitalers, Templars, and Teutonic Knights), the Index of prohibited books, the Inquisition, the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, and Papal infallibility. For further reading: Henry Chadwick, The Early Church (Penguin, 1993) Everett Ferguson, ed., Encyclopedia of Early Christianity (Garland, 1990) J.N.D. Kelly, Early Christian Doctrines (HarperCollins, 1978) 1 The bishop of Rome is generally called the Pope; however, "Pope" was originally a title for any bishop, and is still used today by the patriarchs of Alexandria and Antioch. Jaroslav Pelikan, The Christian Tradition: A History of the Development of Doctrine, 5 vols. (University of Chicago Press, 1971-1983) Steven Runciman, The Eastern Schism (Clarendon Press, 1955) R.W. Southern, Western Society and the Church in the Middle Ages (Penguin, 1970). A large selection from the works of the early Fathers is available in a series entitled Ante-Nicene Fathers, ed. Alexander Roberts and James Donaldson (Eerdmans, 10 vols.). The writings of the Apostolic Fathers are also available in a number of separate editions, such as The Apostolic Fathers, tr. J.B. Lightfoot (1907), Kirsopp Lake (1930), or E.J. Goodspeed (1950), and Early Christian Writings, tr. Maxwell Stanforth & Andrew Louth (1987). Most of these editions also include The Martyrdom of Polycarp. The Sayings of the Fathers has been translated in several different editions, including The Wisdom of the Desert, tr. Thomas Merton (1960), and Wisdom of the Desert Fathers, tr. Benedicta Ward (1975).