inquiry into disability-related harassment executive summary Word

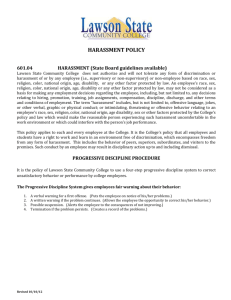

advertisement

Hidden in plain sight Inquiry into disability-related harassment Executive summary 1 Executive summary Key findings Several serious cases of abuse of disabled people – such as Fiona Pilkington and her daughter, Francecca, who died in 2007 after suffering years of harassment – have been reported in the media over the last few years. Our inquiry shows that harassment of disabled people is a serious problem which needs to be better understood. The inquiry has confirmed that the cases of disability-related harassment which come to court and receive media attention are only the tip of the iceberg. Our evidence indicates that, for many disabled people, harassment is a commonplace experience. Many come to accept it as inevitable. Disabled people often do not report harassment, for a number of reasons: it may be unclear who to report it to; they may fear the consequences of reporting; or they may fear that the police or other authorities will not believe them. A culture of disbelief exists around this issue. For this reason, we describe it as a problem which is ‘hidden in plain sight’. There is a systemic failure by public authorities to recognise the extent and impact of harassment and abuse of disabled people, take action to prevent it happening in the first place and intervene effectively when it does. These organisational failings need to be addressed as a matter of urgency and the full report makes a number of recommendations aimed at helping agencies to do so. Any serious attempt to prevent the harassment of disabled people will need to consider more than organisational change, although that will be an important precondition to progress. The bigger challenge is to transform the way disabled people are viewed, valued and included in society. 2 Ten cases As part of this inquiry we examined 10 cases in which disabled people have died or been seriously injured. Our intention in looking at this selection of cases is to illustrate some of the key features of disabilityrelated harassment. They give us some clues as to how and why such behaviour happens, and how, even when it is of a very extreme nature, it can go unchallenged. The victims in these cases were: David Askew, ‘the vulnerable adult’, Keith Philpott, Shaowei He, Christopher Foulkes, Colin Greenwood, Steven Hoskin, Laura Milne, Michael Gilbert and Brent Martin. For more details of the cases please see the full report. The key findings from examining these cases are: Public authorities were often aware of earlier, less serious incidents but had taken little action to bring the harassment to an end. In some cases, no effective action was taken to protect the disabled person even when public authorities were aware of allegations of very serious assaults. This left the disabled person at risk of further harm. Many of the victims in these cases were socially isolated, which put them at greater risk of harassment and violence. The harassment often took place in the context of exploitative relationships. Left unmanaged, non-criminal behaviour and ‘petty’ crime has the potential to escalate into more extreme behaviour. Several of the deaths were preceded by relentless non-criminal and minor criminal behaviour, which gradually increased in frequency and intensity. Public authorities sometimes focused on the victim’s behaviour and suggested restrictions to their lives to avoid harassment rather than dealing with the perpetrators. There was often a failure to share intelligence and co-ordinate responses across different services and organisations. Disability is rarely considered as a possible motivating factor in crime and antisocial behaviour. As a result, the incidents are given 3 low priority and appropriate hate incident policy and legislative frameworks are not applied. Hidden in plain sight The harassment of disabled people is not confined to just a few extreme cases. The incidents which reach the courts and the media are just the most public examples of a profound social problem. For many disabled people, harassment is an unwelcome part of everyday life. Many come to accept it as inevitable, and focus on living with it as best they can. And too often that harassment can take place in full view of other people and the authorities without being recognised for what it is. A culture of disbelief exists around this issue. The harassment of disabled people can take many different forms, including bullying, cyber-bullying, physical violence, sexual harassment and assault, domestic violence, financial exploitation and institutional abuse. Around 1.9 million disabled people were victims of crime in 2009/10. While we do not know exactly how many were victims of harassment, we do know that disabled people are more likely to be victims of crime than people who are not disabled. There are some studies which indicate that disabled people may be more likely to be victims of antisocial behaviour, although more research is needed. Fear of crime and its impact are greater for disabled people. Harassment takes place in many different settings, including in the home, on public transport and in public places, and at school or college. Harassment can be perpetrated by strangers, but also by friends, partners and family members. Disabled people often do not want to report harassment when it occurs, for a range of reasons including fear of consequences, concerns that they won’t be believed and lack of information about who to report it to. 4 Responses to harassment A central aim of this inquiry was to investigate how disability-related harassment is dealt with by public authorities, public transport operators and others. The current system is not succeeding in preventing harassment occurring in the first place; neither is it ensuring that perpetrators face the consequences of their actions. Taken together, this amounts to systemic institutional failure to protect disabled people and their families from harassment. Our key findings are: Incidents are often dealt with in isolation rather than as a pattern of behaviour. There is a lack of consideration by agencies of disability as a possible motivating factor in bullying, antisocial behaviour and crime. As a result, the response to harassment is given low priority and appropriate hate incident policy and legislative frameworks are not applied. Left unmanaged, low level behaviour has the potential to escalate into more extreme behaviour. Opportunities to bring harassment to an end are being missed. There is sometimes a focus on the victim’s behaviour and ‘vulnerability’ rather than dealing with the perpetrators. Agencies do not tend to work effectively together to bring ongoing disability-related harassment to an end. There has been little investment in understanding the causes of harassment and preventing it from happening in the first place. There are barriers to reporting and recording harassment across all sectors. There are barriers to accessing justice, redress and support so most perpetrators face few consequences for their actions and many victims receive inadequate support. There is a lack of shared learning from the most severe cases, so the same mistakes are repeated again and again. 5 Manifesto for change Our inquiry uncovered evidence that there is much which all agencies involved could do to improve their performance in preventing and dealing with disability-related harassment. Our full report sets out specific measures for each relevant sector which our evidence suggests could make a major difference. These include: ministers in key departments, local government leaders, housing providers, the NHS, the police, the courts, schools and public transport operators. Over the next six months we will consult widely with stakeholders on whether these are the right steps, how they might work and whether there are any other measures which might be more effective. We want to find out how these recommendations can be embedded in planned initiatives, and be cost-effective. Most importantly, we recognise that we will only succeed in effecting change when others take responsibility and ownership for these recommendations. At this stage, it is clear that there are seven areas where improvements will show to us that society is achieving real progress in tackling harassment. They require multi-agency co-operation in most instances and a real commitment to effective partnership working if we are to see results. We understand that, in some areas, they may require additional resources and extra cost and we are conscious of the financial and operational constraints which public authorities are under. For this reason we are keen to engage with all parties to find out how the improvement can be achieved for the most reasonable cost. Seven core recommendations There is real ownership of the issue in organisations critical to dealing with harassment. Leaders show strong personal commitment and determination to deliver change. Definitive data is available which spells out the scale, severity and nature of disability harassment and enables better monitoring of the performance of those responsible for dealing with it. The criminal justice system is more accessible and responsive to victims and disabled people and provides effective support to them. 6 We have a better understanding of the motivations and circumstances of perpetrators and are able to more effectively design interventions. The wider community has a more positive attitude towards disabled people and better understands the nature of the problem. Promising approaches to preventing and responding to harassment and support systems for those who require them have been evaluated and disseminated. All frontline staff who may be required to recognise and respond to issues of disability-related harassment have received effective guidance and training. There is real ownership of the issue in organisations critical to dealing with harassment. Leaders show strong personal commitment and determination to deliver change Our evidence shows the most critical factor in organisations improving their performance, is the level of commitment and determination to address the issue shown by their leaders. It is, after all, senior officers and executives who set the priorities for organisations. If there is a real and visible commitment to change at the most senior level then it is likely that this will drive real change throughout the organisations which they lead. In addition to showing leadership within their organisations, we would expect leaders to embrace public accountability. Transparency over performance is one aspect to this – which involves a real commitment to share data which shows how their organisation is performing. Another aspect is the display of a personal willingness to be publicly accountable for any serious instances which occur in their area. Finally, we would expect this personal commitment to be formally recognised within public authorities’ core objectives, either within their governance structures or otherwise. Definitive data is available which spells out the scale, severity and nature of disability harassment and enables better monitoring of the performance of those responsible for dealing with it While our inquiry has uncovered a great deal about disability-related harassment, there remains much which we don’t know. Without comprehensive data, across all agencies, it will be impossible for our society to properly respond. In the interests of transparency, we also 7 need public authorities to publish their performance so that the public can assess how they are performing. We recommend that all data systems in these agencies: are able to record whether the victim is a disabled person (and/or has another type of protected characteristic) are able to determine: o whether the incident was motivated by the victim’s disability and/or any other form of protected characteristic o the clearly identified lead officer who will take the issue forward o whether or not this is a first instance of harassment or part of a more general, or escalating, pattern o the priority status accorded to each incident in relation to risk to the victim or, if known, motives and circumstances of the perpetrator o where harassment persists, whether and to what extent priority status should be given to a situation o which other local agencies have been alerted to the problem or, if this has not occurred, why not and under what circumstances should such agencies become involved. Also what appropriate partnership arrangements should be in place enable identification of all ongoing or repeat instances to avoid the anxiety and risk that such instances of behaviour will become progressively more serious share data across agencies and identify solutions to effective data sharing, particularly where lives may be at risk, to ensure that all involved have a comprehensive picture. The criminal justice system is more accessible and responsive to victims and disabled people and provides effective support to them Another major requirement of the general response to disability-related harassment, and other forms of crime and antisocial behaviour, is that victims feel adequately supported by all the agencies involved and that these agencies respond to their concerns effectively. 8 Wherever a disabled person first reports an incident, the route to reporting, and ultimately the criminal justice system, needs to be clear and unhindered. We recommend the following: - all agencies involved with dealing with the issue should review, and, where necessary, remove all obstacles to the reporting of disability-related harassment. This will, in particular, involve seeking the views of disabled people and their representatives - the police and prosecution services should always establish whether a victim is disabled and, if they are, should consider whether that may be a factor in why the crime/incident occurred. They should not rely solely on the victim’s perception. They should reconsider this at several stages throughout the investigation. Crimes against disabled people should rarely be considered motiveless. We have a better understanding of the motivations and circumstances of perpetrators and are able to more effectively design interventions One fundamental issue in dealing with the problem of disability-related harassment, and other forms of abuse, is to understand why it occurs. The most urgent issue is getting a better understanding of the characteristics and motivations of those who commit acts of disabilityrelated harassment. In addition, there needs to be more awareness of the general structures and attitudes (and the interactions between them) which give rise to the problem in the first place. To address these issues, we recommend that: - targeted research is undertaken in collaboration with National Offender Management Service and local authorities in Scotland to build a clearer picture of perpetrator profiles, motivations and circumstances and, in particular, to inform prevention and rehabilitation - criminal justice agencies support bodies that commission research to stimulate and support studies that look into why harassment occurs in the first place and broader attitudes towards disabled people. 9 The wider community has a more positive attitude towards disabled people and better understands the nature of the problem With the possible exception of some of the cases which are given a high profile by the media, disability-related harassment does not seem to be perceived as serious or widespread by the public. It is, as we describe, hidden in plain sight. Changing wider public attitudes towards the seriousness of such harassment, and more general social attitudes towards disabled people, forms an important part of a wider solution. In order to initiate change in this area, we recommend that public authorities: - review the effectiveness of current awareness-raising activities concerning disability-related harassment where they exist and assess where gaps in their campaigns could usefully be filled - use the public sector equality duty as a framework for helping promote positive images of disabled people and redress disproportionate representation of disabled people across all areas of public life - encourage all individuals and organisations to recognise, report and respond to any incidences of disability-related harassment they may encounter. All frontline staff who may be required to recognise and respond to issues of disability-related harassment have received proper training It is clear from our evidence that reporting of and responses toharassment would both be improved substantially with better training for frontline staff providing public services. The cases show that even staff such as environmental health officers may come across instances of harassment and the ability to make appropriate safeguarding referrals could make a significant difference to people’s lives. To address these issues, we recommend that: - all frontline staff working in all agencies, whether public authorities or voluntary and private sector organisations, where disability-related harassment, antisocial behaviour or other similar forms of activity are likely to be an issue, are trained in how to recognise and ensure appropriate safeguarding - more generally all agencies should consider whether their wider staff training and development processes and appraisal and 10 promotion systems should be amended to ensure such knowledge becomes embedded and an incentive for better job performance - staff gain an understanding of disability equality matters and appropriate engagement with disabled service users. Promising approaches to preventing and responding to harassment have been evaluated and disseminated There is much in what many public bodies are doing which might emerge as good practice and create vital learning which other bodies can follow to help reduce the problem. However, many of these promising approaches are in their infancy and as yet we do not know conclusively what works and what doesn’t. Therefore, we recommend that public bodies conduct rigorous evaluation of their response and prevention projects over a three year time frame so that we can build a shared knowledge of the most effective routes to take to deal with harassment and reduce its occurrence. All evaluations should then be widely and openly shared so that all bodies can learn from them. More detailed recommendations can be found in the full report in respect of key sectors including: Education Criminal justice Local and central government Health Housing Social care Transport Partnerships Regulators and inspectorates 11 Contacts England Arndale House The Arndale Centre Manchester M4 3AQ Helpline: Telephone 0845 604 6610 Textphone 0845 604 6620 Fax 0845 604 6630 Scotland The Optima Building 58 Roberston Street Glasgow G2 8DU Helpline: Telephone 0845 604 5510 Textphone 0845 604 5520 Fax 0845 604 5530 Wales 3rd Floor 3 Callaghan Square Cardiff CF10 5BT Helpline: Telephone 0845 604 8810 Textphone 0845 604 8820 Fax 0845 604 8830 12 Helpline opening times: Monday to Friday 8am–6pm If you would like this publication in an alternative format and/or language please contact the relevant helpline to discuss your requirements . All publications are also available to download in a variety of formats from our website: www.equalityhumanrights.com/dhfi 13