Critical Thinking Booklet

Psychology

Eighth Edition

Douglas A. Bernstein, Louis A. Penner,

Alison Clarke-Stewart, and Edward J. Roy

William S. Altman

Douglas A. Bernstein

Houghton Mifflin Company

BOSTON NEW YORK

Sponsoring Editor: Jane Potter

Marketing Manager: Amy Whitaker

Marketing Assistant: Samantha Abrams

Senior Development Editor: Laura Hildebrand

Editorial Associate: Henry Cheek

Copyright © 2008 by Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

Houghton Mifflin Company hereby grants you permission to reproduce the Houghton Mifflin

material contained in this work in classroom quantities, solely for use with the accompanying

Houghton Mifflin textbook. All reproductions must include the Houghton Mifflin copyright

notice, and no fee may be collected except to cover the cost of duplication. If you wish to make

any other use of this material, including reproducing or transmitting the material or portions

thereof in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including any information storage

or retrieval system, you must obtain prior written permission from Houghton Mifflin Company,

unless such use is expressly permitted by federal copyright law. If you wish to reproduce

material acknowledging a rights holder other than Houghton Mifflin Company, you must obtain

permission from the rights holder. Address inquiries to College Permissions, Houghton Mifflin

Company, 222 Berkeley Street, Boston, MA 02116–3764.

Contents

Preface ................................................................................................................ IV

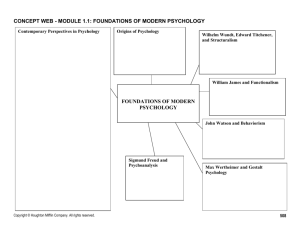

Chapter 1—Introducing Psychology.....................................................................1

Chapter 2—Research in Psychology ....................................................................5

Chapter 3—Biological Aspects of Psychology ....................................................9

Chapter 4—Sensation ........................................................................................ 13

Chapter 5—Perception ....................................................................................... 18

Chapter 6—Learning.......................................................................................... 22

Chapter 7—Memory .......................................................................................... 26

Chapter 8—Cognition and Language ................................................................ 30

Chapter 9—Consciousness ................................................................................ 35

Chapter 10—Cognitive Abilities ....................................................................... 39

Chapter 11—Motivation and Emotion .............................................................. 44

Chapter 12—Human Development ................................................................... 48

Chapter 13—Health, Stress, and Coping ........................................................... 52

Chapter 14—Personality .................................................................................... 56

Chapter 15—Psychological Disorders ............................................................... 61

Chapter 16—Treatment of Psychological Disorders ......................................... 66

Chapter 17—Social Cognition ........................................................................... 70

Chapter 18—Social Influence ............................................................................ 74

Chapter 19—Neuropsychology ......................................................................... 79

Chapter 20—Industrial/Organizational Psychology Summary ......................... 84

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

IV

Engaging in Critical Thinking in Psychology

Many educators rhapsodize about critical thinking (although often in rather vague terms) as a

desirable activity that everyone should integrate into their course work. It might be easy to

dismiss critical thinking as just another educational fad. But it isn’t.

Critical thinking is simply another way to describe the process psychologists use when

approaching a problem. We begin by describing the behaviors or phenomena that interest us; we

attempt to develop explanations for them; we develop and test hypotheses, then attempt to

predict outcomes based on our explanations; and we draw conclusions based on the results. In

the process, we learn a great deal about the elements of the problem, their interrelationships, and

connections to familiar ideas.

Some researchers have found that if you use critical thinking when you write about a topic,

you’re likely to learn more and to understand the material better (Tynjälä, 1998; Wade, 1995).

Pena-Shaff and Nicholls (2004) found that students better understood information when engaged

in critical thinking in online discussions. And, according to Kowalski and Taylor (2004) students

who engaged in critical thinking were more likely to change their initial misconceptions about

psychology than those who didn’t think critically.

Many different people use critical thinking in all kinds of ways. You might be familiar with a

television show called Mythbusters, in which Adam Savage and Jamie Hyneman use critical

thinking and experimental methods to look for the truth behind urban legends and other common

misconceptions (Loxton, 2005). If you’re interested in psychic phenomena, you may want to see

how the James Randi Educational Foundation (at http://randi.org/) applies critical thinking to

people’s claims of paranormal abilities.

The exercises in this booklet present ideas, beliefs, and statements, which are linked to each

chapter in Essentials of Psychology (Bernstein & Nash, 2008). You’ll be asked to evaluate these

ideas, beliefs, and statements using the critical thinking method. Because we want you to

concentrate on learning to think critically, we’ve provided some source material for each

question. You might want to look for more information, using appropriate search engines such as

PsycARTICLES® or PsycINFO®, or by working with your school’s library or tutoring staff.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

V

Critical thinking isn’t just helpful for your school work, or for making decisions about which car

to buy or how to invest your savings. It’s also a fun way to learn. Students who used critical

thinking in online discussions (Pena-Shaff, Altman, & Stephenson, 2005) or in the classroom

(Hays & Vincent, 2004) said it helped them learn better and develop their communication skills.

So, when we engage in critical thinking, we learn more, deepen our understanding of what we

already know, learn more effective ways to communicate with other people, and have a lot more

fun in the process. We hope you’ll enjoy working on these critical thinking exercises, and that

they’ll stimulate your curiosity, ingenuity, and sense of intellectual play.

Be well, and enjoy!

William S. Altman, Ph.D.

Psychology and Human Services Department

Broome Community College, Binghamton, NY

References

Bernstein, D. A., & Nash, P. W. (2008). Essentials of Psychology (4th ed.). New York:

Houghton Mifflin.

Hays, J. R., & Vincent, J. P. (2004). Students’ evaluation of problem-based learning in

graduate psychology courses. Teaching of Psychology, 31, 124–126.

Kowalski, P., & Taylor, A. K. (2004). Ability and critical thinking as predictors of change in

students’ psychological misconceptions. Journal of Instructional Psychology, 31,

297–303.

Loxton, D. (2005). Mythbusters exposed: How a special effects crew opened the most

important new front in the battle for science literacy. Skeptic, 12(1), 34–42.

Pena-Shaff, J., Altman, W., & Stephenson, H. (2005). Asynchronous online discussions as a

tool for learning: Students’ attitudes, expectations, and perceptions. Journal of

Interactive Learning Research, 16, 409–430.

Pena-Shaff, J. B., & Nicholls, C. (2004). Analyzing student interactions and meaning

construction in computer bulletin board discussions. Computers & Education, 42,

243–265.

Tynjälä, P. (1998). Writing as a tool for constructive learning: Students’ learning experiences

during an experiment. Higher Education, 36, 209–230.

Wade, C. (1995). Using writing to develop and assess critical thinking. Teaching of

Psychology, 22, 24–28.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

1

CHAPTER

1

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 1.1:

Assessing the Impact of Legislation

Governments often enact laws to solve particular social problems or to lessen their impacts. One

example is the No Child Left Behind (NCLB) Act of 2002. Its purpose was to improve the

quality of children’s education in the United States, and according to the Department of

Education, the law is working as intended (http://www.ed.gov/nclb/landing.jhtml).

One way in which the NCLB is supposed to help raise academic achievement is through testing,

to determine whether there is actually improvement in the education of children. However, the

National Center for Fair and Open Testing claims this approach has failed. You can read their

statements about NCLB at (http://fairtest.org/nattest/bushtest.html).

Researchers have looked at NCLB from a variety of perspectives. Smith (2005) and Johnson

(2006) provide overviews of the law, its intentions, and some of its possible consequences.

Others have looked at NCLB’s impacts on gifted children (Mendoza, 2006), music education

(Circle, 2005), and visually impaired children (Ferrell, 2005).

Use the critical thinking method outlined in your textbook to determine whether NCLB is

working as intended. Be sure to look carefully at your sources to determine whether they are

credible and accurate, or just someone’s opinion. The basis for critical thinking is the use of

evidence. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Circle, D. (2005). To test or not to test? Music Educators Journal, 92(1), 4.

Ferrell, K. A. (2005). The effects of NCLB. Journal of Visual Impairment & Blindness, 99,

681–683.

Johnson, A. P. (2006). No child left behind: Factory models and business paradigms.

Clearing House, 80(1), 34–36.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

2

Mendoza, C. (2006). Inside today’s classrooms: Teacher voices on No Child Left Behind and

the education of gifted children. Roeper Review, 29, 28–31.

National Center for Fair and Open Testing. (n.d.). Federally mandated testing page: NCLB.

Retrieved December 29, 2007, from http://fairtest.org/nattest/bushtest.html.

Smith, E. (2005). Raising standards in American schools: The case of No Child Left Behind.

Journal of Education Policy, 4, 507–524.

United States Department of Education. (n.d.) No Child Left Behind—ED.gov. Retrieved

December 29, 2007, from http://www.ed.gov/nclb/landing.jhtml.

ACTIVITY 1.2:

Grade Inflation

Many people believe that today’s students are getting higher grades for doing less work, or work

of lower quality than students of previous generations. Media outlets report that grade inflation is

a problem at most colleges, as illustrated by reports from USA Today (2002) and Wikipedia

(2006). Organizations such as GradeInflation.com (http://gradeinflation.com/) report that grade

inflation is rampant and becoming more serious. Yet Ellenberg (2002) and Kohn (2002) suggest

that it may not be such a problem.

What is closer to the truth? Use the critical thinking approach to decide whether grade inflation is

real. If so, is it a major problem or something not worthy of concern? Be sure to look carefully at

your sources to determine whether they are credible and accurate, or just someone’s opinion.

Remember that the basis for critical thinking is the use of evidence.

Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Ellenberg, J. (2002, October 2). Don’t worry about grade inflation: Why it doesn’t matter

that professors give out so many A’s. Slate. Retrieved December 29, 2007, from

http://www.slate.com/id/2071759/.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

3

Grade inflation. (2006, December 28). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved

December 29, 2006, from http://en.wikipedia.org/w/

index.php?title=Grade_inflation&oldid=96950800.

Ivy League grade inflation [Electronic version]. (2002, February 27). USA Today. Retrieved

December 29, 2006, from http://www.usatoday.com/news/opinion/2002/02/08/

edtwof2.htm.

Kohn, A. (2002). The dangerous myth of grade inflation. Chronicle of Higher Education;

49(11), pB7. Retrieved December 29, 2007, from EBSCO Academic Premier

database.

ACTIVITY 1.3:

Do We Use Only 10% of Our Brains?

The famous American psychologist William James (1907) once said, “Compared with what we

ought to be, we are only half awake. Our fires are damped, our drafts are checked. We are

making use of only a small part of our possible mental and physical resources” (p. 323).

Many people believe we all have a great deal of untapped mental potential. Some think it’s based

in a kind of reserve of intelligence, while others believe in paranormal abilities that have not yet

been developed. Often, they’ll explain this by saying that we only use 10% of our brains.

Perhaps your parents or teachers may have mentioned this to you.

Creative Alternatives (Superconscious, 2007), CornerBar PR (Industry appetizers, n.d.), and

other commercial sites all quote the 10% figure. Many, such as self-described psychic Uri Geller

(n.d.), attribute it to Albert Einstein, while others cite Margaret Mead or other famous

researchers. Anitei (n.d.) at Softpedia cites data from brain scanning studies to show that we only

use about 20% of our brains when making memories. It’s worth noting that many of these

organizations and individuals also provide materials or services, which they claim are designed

to help you activate the slumbering part of your total potential.

Many psychologists, such as Chudler (1997), call the 10% figure a myth. Several (Genovese,

2004; Radford, 2000) have sought to explain or debunk the idea that we only use 10% of our

brain. Yet the belief persists despite the efforts of psychologists and psychology instructors

(Standing & Huber, 2003). Could this be because it really is true?

Do we have massive untapped resources in our brains? Use the critical thinking method to come

to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source material.

Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1. What am I being asked to believe or accept?

2. What evidence is there to support the assertion?

3. Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

4

4. What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

5. What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Anitei, S. (n.d.). We use just 20% of out brains to make memories. Retrieved July 20, 2007,

from http://news.softpedia.com/news/We-Use-Just-20-of-the-Brain-to-MakeMemories-52643.shtml.

Chudler, E. (1997). Myths about the brain: 10 percent and counting. Retrieved September 4,

2007, from http://www.brainconnection.com/topics/?main=fa/brain-myth.

Geller, U. (n.d.) Uri Geller. Retrieved July 20, 2007, from http://www.uri-geller.com/

lbmp_print.htm.

Genovese, J. E. C. (2004). The ten percent solution. Skeptic, 10(4), 55–57.

Industry appetizers: Overheard at the bar. (n.d.). CornerBar PR. Retrieved July 20, 2007,

from http://www.cornerbarpr.com/industryappetizers/overheard.cfm?article=1033.

James, W. (1907). The energies of men [Electronic version]. Science, 25(635), 321–332.

Retrieved July 20, 2007, from Classics in the History of Psychology Web site:

http://psychclassics.yorku.ca/James/energies.htm.

Radford, B. (2000). The ten-percent myth. Retrieved July 20, 2007 from

http://snopes.com/science/stats/10percnt.htm.

Standing, L. G., & Huber, H. (2003). Do psychology courses reduce beliefs in psychological

myths? Social Behavior & Personality: An International Journal, 31, 585–592.

Superconscious interview with Melvin Saunders. (2007). Creative Alternatives. Retrieved

July 20, 2007, from http://www.mind-course.com/interview.html.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

5

CHAPTER

2

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 2.1:

The Effectiveness of Peer Review

The scientific community relies on a process called peer review (see a good definition and

discussion of peer review in Wikipedia) to ensure that information published in scientific

journals is accurate. Yet there are still major problems associated with the peer review process,

and much inaccurate or misleading material may still be published. Weiss (2005) details many

sorts of scientific misconduct that may not be detected by the peer review process. The issues

surrounding the effectiveness of peer review are discussed in depth by Fox (1994) and Lundberg

(2002). Still, most scientists seem to feel that the peer review process is the best way to ensure

scientific integrity.

Use the critical thinking approach to determine whether peer review is an effective method for

maintaining honesty in scientific research. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source

material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Fox, M. F. (1994). Scientific misconduct and editorial and peer review processes. Journal of

Higher Education, 65(3), 298–309.

Lundberg, G. D. (2002). The publishing dilemma of the American Psychological

Association. American Psychologist, 57, 211–212.

Weiss, R. (2005, June 9). Many scientists admit to misconduct [Electronic version].

Washington Post. Retrieved December 29, 2007, from

http://www.washingtonpost.com.

Peer review. (2006, December 27). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved

December 29, 2006, from

http://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Peer_review&oldid=96718551.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

6

ACTIVITY 2.2:

Reiki

Practitioners of Reiki claim that it is a technique through which they can heal many physical,

mental, and emotional conditions. According to Wikipedia, it was developed in Japan in the

early 20th century. While Reiki masters have extolled its effectiveness (Rand, n.d.), skeptics

claim that it is nothing more than quackery or fraud (Carroll, 2002). Some researchers (Rosa,

Rosa, Sarner, & Barrett, 1998) have attempted to determine the effectiveness of Reiki.

Is Reiki a real phenomenon, or are the skeptics correct? Use the critical thinking method to come

to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source material.

Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Carroll, R. T. (2002). Reiki. In The Skeptic’s Dictionary. Retrieved January 13, 2007 from

http://skepdic.com/reiki.html.

Rand, W. L. (n.d.). The international center for Reiki training. In The International Center

for Reiki Training Web site. Retrieved January 13, 2007, from http://www.reiki.org.

Reiki. (2006, November 17). In Wikipedia, The Free Encyclopedia. Retrieved January 13,

2007, from http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reiki.

Rosa, L., Rosa, E., Sarner, L., & Barrett, S. (1998). A close look at therapeutic touch. JAMA:

The Journal of the American Medical Association, 279, 1005–1010.

ACTIVITY 2.3:

Loony for Luna

For centuries, people have believed that the full moon causes insane behavior. Sources report

links between the full moon and binge drinking, criminal disturbances, and violent crimes such

as murder (Sims, 2007; Tasso & Miller, 1976; Townley, 1997). Townley (1977) also reports

statistically significant correlations between the phase of the moon and the number of medical

procedures performed, the conception of children, and other phenomena. Lieber and Sherin

(1972) found a significant link between the lunar phase and the number of homicides in Dade

County, Florida, as well as a relationship between the phase of the moon and the level of

violence or strangeness of the homicides. Further confirmation of a relationship between lunar

cycle and insanity comes from Blackman and Catalina (1973) who correlated the phase of the

moon with the number of admissions to a mental health center emergency room.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

7

Other researchers dismiss the influence of the moon on such phenomena. Campbell and Beets

(1978) found no relationship between the phase of the moon and the number of psychiatric

hospital admissions, suicides, or homicides. They suggest that any findings to the contrary are a

particular type of statistical error. This echoes the findings of Walters, Markeley, and Tiffany

(1975), who studied the relationship between lunar phases and the number of emergency contacts

to a community mental health facility. A meta-analysis of 37 studies (Rotton & Kelly, 1985) also

refuted the supposed link between madness and the moon, attributing any links to various errors

on the parts of some other researchers. Similar findings were reported more recently by Owens

and McGowan (2006).

However, in an article looking at both the positive and negative findings of various researchers in

this area, Vines (2001) posits a possible explanation that might link the phase of the moon to

human behavior, taking social and historical technological change into account, along with data

on human biorhythms.

Does the moon influence human behavior? Use the critical thinking method to come to your own

conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in

thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Blackman, S., & Catalina, D. (1973). The moon and the emergency room. Perceptual and

Motor Skills, 37, 624–626.

Campbell, D. E., & Beets, J. L. (1978). Lunacy and the moon. Psychological Bulletin, 85,

1123–1129.

Lieber, A. L., & Sherin, C. R. (1972). Homicides and the lunar cycle: Toward a theory of

lunar influence on human emotional disturbance. American Journal of Psychiatry,

129, 69–74.

Owens, M., & McGowan, I. W. (2006). Madness and the moon: The lunar cycle and

psychopathology. German Journal of Psychiatry, 9(1), 123-127.

Rotton, J., & Kelly, I. W. (1985). Much ado about the full moon: A meta-analysis of lunarlunacy research. Psychological Bulletin, 97, 286–306.

Sims, P. (2007, June 7). British cops shine light on late-night lunacy. The Courier Mail.

Retrieved on 4 September, 2007, from http://www.news.com.au/story/

0,23599,21864175-13762,00.html.

Tasso, J., & Miller, E. (1976). The effects of the full moon on human behavior. The Journal

of Psychology, 93, 81–83.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

8

Townley, J. (1997). Can the full moon affect human behavior [Electronic version]?

In J. Townley Dynamic Astrology: Using Planetary Cycles to Make Personal and

Career Choices. Rochester, VT: Destiny Books. Retrieved on July 23, 2007, from

http://www.innerself.com/Astrology/full_moon.htm.

Vines, G. (2001, June 23). Blame it on the moonlight [Electronic copy]. New Scientist,

170(2296), 36–39. Retrieved July 23, 2007, from EBSCO Academic Premier

database.

Walters, E., Markley, R. P., & Tiffany, D. W. (1975). Lunacy: A type I error? Journal of

Abnormal Psychology, 84, 715–717.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

9

CHAPTER

3

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 3.1:

Is There a Biological Basis for Morality?

What is the source of morality? Recently, some scholars have suggested that morality is not

something learned, but is inherent in the biological structure of the brain (Broom, 2006). Others

believe it is something that is not at all connected to biology, but to other factors such as identity

(Hardy & Carlo, 2005), parental influence (White & Matawie, 2004), and temperament (Kagan,

2005). Some psychologists (Flack & de Waal, 2000; Loye, 2002) look at the evolutionary basis

of morality, as well.

Use the critical thinking approach to determine whether morality is biologically based and a

result of the evolution of the brain. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source

material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Broom, D. M. (2006). The evolution of morality. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 100,

20–28.

Flack, J. C., & de Waal, F. B. M. (2000). Any animal whatever: Darwinian building blocks

of morality in monkeys and apes. Journal of Consciousness Studies, 7(1–2), 1–29.

Hardy, S. A. & Carlo, G. (2005). Identity as a source of moral motivation. Human

Development, 48, 232–256.

Kagan, J. (2005). Human morality and temperament. Nebraska Symposium on Motivation,

51, 1–32.

Loye, D. (2002). The moral brain. Brain and Mind, 3, 133–150.

White, F. A. & Matawie, K. M. (2004). Parental morality and family processes as predictors

of adolescent morality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 219–233.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

10

ACTIVITY 3.2:

The Age of Responsibility

The psychologist G. Stanley Hall linked adolescence to all sorts of social problems (Hall, 1904).

Little seems to have changed in over 100 years—current newspapers and magazines are

constantly bombarding us with information about the terrible nature of adolescents. They tell us

that teenagers all over the world are violent, evil people who will kill or hurt others on impulse

(Arinde, 2006; Larimer, 2000). They’re responsible for all sorts of crime; the tide of adolescent

viciousness is rising.

Steinberg and Scott (2003) argue that adolescents should not be held responsible for murder or

other similar infractions, as their brains have not yet reached maturity. Beckman (2004) provides

a good overview of some of the issues involved. Others posit that the relative immaturity of the

adolescent is not the causal factor in such crimes. They mention factors such as parental levels of

morality (White & Matawie, 2004), depression (Ritakallio, Kaltiala-Heino, Kivivuori,

Luukkaala, & RimpelÄ, 2006), and community violence (Patchin, Huebner, McClusky, Varano,

& Bynum, 2006).

Use the critical thinking approach to determine whether Steinberg and Scott are correct in stating

that adolescents should not be held to the same degree of responsibility for their immoral actions

as adults. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in

thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Arinde, N. (2006, February 16). Gangland, New York City, part 2. New York Amsterdam

News, 97(8), pp. 3, 34.

Beckman, M. (2004). Crime, culpability, and the adolescent brain. Science, 305, 596–599.

Hall, G. S. (1904). Adolescence—Its psychology and its relations to physiology,

anthropology, sociology, sex, crime, religion, and education. New York: D. Appleton

and Company.

Larimer, T. (2000, August 28). Natural-born killers? Time, 156(9), 37.

Patchin, J. W., Huebner, B. M., McClusky, J. D., Varano, S. P., & Bynum, T. S. (2006).

Exposure to community violence and childhood delinquency. Crime & Delinquency,

52, 307–332.

Ritakallio, M., Kaltiala-Heino, R., Kivivuori, J., Luukkaala, T., & RimpelÄ, M. (2006).

Delinquency and the profile of offences among depressed and non-depressed

adolescents. Criminal Behaviour & Mental Health, 16, 100–110.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

11

Steinberg, L. & Scott, E. S. (2003). Less guilty by reason of adolescence: Developmental

immaturity, diminished responsibility, and the juvenile death penalty. American

Psychologist, 58, 1009–1018.

White, F. A. & Matawie, K. M. (2004). Parental morality and family processes as predictors

of adolescent morality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 13, 219–233.

ACTIVITY 3.3:

He Thinks, She Thinks

In 2005, Lawrence H. Summers stirred up a major controversy when he spoke at the National

Bureau of Economic Research Conference on Women and Science. In his apology, Summers

(2005) says that he unintentionally gave the impression that men were biologically better

qualified to succeed in the sciences than women. This has generated a good deal of scientific and

political debate, with many intelligent people arguing on both sides of the issue. Some

neuroscientists provide arguments for (Hines, Chiu, McAdams, Bentler, & Lipcamon, 1992) or

against (Byne, Bleier, & Houston, 1988) gender differences based on the structure of the brain,

specifically a part of the brain called the corpus callosum. Other sources cite discrimination

(Committee on Women Faculty in the School of Science, 1999), differing levels of “job

involvement” and perceived levels of autonomy (Lorence, 2001), or socialization (Roger &

Duffield, 2000) as the source of differences in women and men’s success in the sciences.

What is closer to the truth? Are men biologically better adapted to scientific work than women?

Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your

thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer

the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Byne, W., Bleier, R., & Houston, L. (1988). Variations in human corpus callosum do not

predict gender: A study using magnetic resonance imaging. Behavioral Neuroscience,

102, 222–227.

Committee on Women Faculty in the School of Science. (1999). A study on the status of

women faculty in science at MIT: How a committee on women faculty came to be

established by the dean of the School of Science, what the committee and the dean

learned and accomplished, and recommendations for the future. Retrieved December

29, 2006, from MIT Web site: http://web.mit.edu/fnl/women/women.pdf.

Hines, M., Chiu, L., McAdams, L. A., Bentler, P. M. & Lipcamon, J. (1992). Cognition and

the corpus callosum: Verbal fluency, visuospatial ability, and language lateralization

related to midsagittal surface areas of callosal subregions. Behavioral Neuroscience,

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

12

106, 3–14.

Lorence, J. (2001). A test of “gender” and “job” models of sex differences in job

involvement. Social Forces, 66, 121–142.

Roger, A. & Duffield, J. (2000). Factors underlying persistent gendered option choices in

school science and technology in Scotland. Gender & Education, 12, 367–383.

Summers, L. H. (2005). Letter from President Summers on women and science. Retrieved

December 29, 2006, from Harvard University, Office of the President Web site:

http://www.president.harvard.edu/speeches/2005/womensci.html.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

13

CHAPTER

4

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 4.1:

Hey Kid, Turn Down That Darned Noise!

Apple’s iPod™ and other music players have become incredibly popular. Wired Magazine

reports that despite the fact that Microsoft manufactures a competing product, the iPod is wildly

popular on the Microsoft campus, much to the annoyance of Microsoft founder Bill Gates

(Kahney, 2005). Even colleges and universities are using iPods to disseminate information to

students and others, and for use in student projects (Brandeis, 2005; Broome, 2007; Martin,

2007).

And yet, many researchers (Geiger, 2006; Moore, 2006; Shafer, 2006) warn that using the iPod

may damage your hearing. This may be due to of the design of the earbuds (Keizer, 2005) or the

volumes at which people listen (Hitti, 2006). In fact, a class-action suit regarding this has been

filed against Apple (Keizer, 2006).

Are these worries overblown? Would colleges and universities promote the use of a technology

that causes relatively permanent harm to its users? Is the iPod dangerous? Have your experiences

with iPods been good or bad? Do you see valid points on both sides?

Use the critical thinking method to evaluate the evidence and decide if the iPod is dangerous. Be

sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically,

you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Brandeis University. (2005). Welcome to the home of the iPod experience! Retrieved July

23, 2007, from Brandeis University Web site: http://lts.brandeis.edu/teachlearn/ipod/

index.html.

Broome Community College. (2007). About BCC on iTunes U. Retrieved on July 23, 2007,

from Broome Community College Web site: http://itunes.sunybroome.edu/

overview.php.

Geiger, D. (2006). When modern life pumps up the volume, give your ears some TLC.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

14

Retrieved on July 23, 2007, from CNN.com Web site: http://www.cnn.com/2007/

HEALTH/04/10/healthmag.hearing/.

Hitti, M. (2006, March 16). Teens’ MP3 habits may up hearing loss: Adults listen longer, but

teens turn the volume up higher. Retrieved on July 23, 2007, from WebMD Medical

News Web site: http://www.webmd.com/news/20060316/

teens-mp3-habits-may-up-hearing-loss.

Kahney, L. (2005, February 2). Hide your iPod, here comes Bill. Retrieved on July 23, 2007,

from Wired Magazine Web site: http://www.wired.com/print/gadgets/mac/

commentary/cultofmac/2005/02/66460.

Keizer, G. (2005, December 19). Eh? iPod earbuds can cause hearing loss. Retrieved on July

23, 2007, from Information Week Web site: http://www.informationweek.com/story/

showArticle.jhtml?articleID=175006733.

Keizer, G. (2006, February 2). Apple hit with iPod hearing loss lawsuit. Retrieved on July

23, 2007, from Information Week Web site: http://www.informationweek.com/story/

showArticle.jhtml?articleID=178601009.

Martin, N. (2007, May 25). iPod study plants seeds of change. Retrieved on July 23, 2007,

from Texas Tech Today Web site:

http://www.depts.ttu.edu/communications/news/stories/

07-05-food-safety-ipod.php.

Moore, M. (2006). Hispanics may face higher risk for hearing loss from iPods, other MP3

players. ASHA Leader, 11(17), 3,17.

Shafer, D. N. (2006). Noise-induced hearing loss hits teens. ASHA Leader, 11(5), 1, 27.

ACTIVITY 4.2:

Blind People Hear Better

As you know, people are highly adaptable. If something goes wrong in your life, you can often

compensate for it by changing other aspects of what you do. Many people believe that when

someone has an impaired sense, such as sight, they can compensate by developing more

sensitivity in one of their other senses. For example, it is often said that blind people have more

sensitive hearing than sighted people. Locke, Voltaire, and other philosophers subscribed to that

theory, and many of us might want to believe it; it has a certain ring of fairness to it—a loss in

one part of a person’s life is compensated by a gain in another.

Many psychologists consider this sort of compensation a myth, citing such concepts as the all-ornothing principle (recall the discussion of action potentials and the firing of neurons in your

textbook, Bernstein, Penner, Clarke-Stewart, & Roy, 2008) which states that neurons either fire

or don’t fire, but cannot fire by degrees. They also point out that the physical structures of

hearing (pinnae, tympanic membrane, bones of the middle ear, etc.) are the same for blind and

sighted individuals (see the diagram in your book, Bernstein et al., 2008, p. 114).

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

15

However, other psychologists have looked at the plasticity of the brain, which suggests that

compensation might be possible (recall the discussion of plasticity in Bernstein, et al., 2008).

Sahlman and Koper (1992) found that blind individuals detected lies with far greater accuracy

than sighted individuals. Furthermore, people who lost their sight early in life had a greater

ability to locate the sources of sounds than sighted individuals (Lessard, Paré, Lepore, &

Lassonde, 1998). These results were echoed by Voss, Lassonde, Gougoux, Fortin, Guillemot,

and Lepore (2004), who posited that this greater ability might be due to early reorganization of

the cortex, a theory supported by the work of Rauschecker and Korte (1993), who found such

reorganization in the brains of cats. Yet other researchers (Morgan, 1999; Zwiers, Van Opstal, &

Cruysberg, 2001) point out numerous flaws in such experiments.

Do blind people compensate for their lack of sight by developing better hearing? Use the critical

thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible

source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following

questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Bernstein, D. A., Penner, L. A., Clarke-Stewart, A., & Roy, E. J. (2008). Psychology (8th

ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Lessard, N., Paré, M., Lepore, F., & Lassonde, M. (1998). Early-blind human subjects

localize sound sources better than sighted subjects. Nature, 395(6699), 278–280.

Morgan, M. (1999). Sensory perception: Supernormal hearing in the blind? Current Biology,

9, 53–54.

Rauschecker, J. P., & Korte, M. (1993). Auditory compensation for early blindness in cat

cerebral cortex. Journal of Neuroscience, 13, 4538–4548.

Sahlman, J. M., & Koper, R. J. (1992, May). Do you hear what I hear?: Deception detection

by the blind. Paper presented at the annual meeting of the International

Communication Association, Miami, FL. (ERIC Document Reproduction Service No.

EC301405.

Voss, P., Lassonde, M., Gougoux, F., Fortin, M., Guillemot, J.-P., & Lepore, F. (2004).

Early- and late-onset blind individuals show supra-normal auditory abilities in farspace. Current Biology, 14, 1734–1738.

Zwiers, M. P., Van Opstal, A. J., & Cruysberg, J. R. M. (2001). A spatial hearing deficit in

early-blind humans. Journal of Neuroscience, 21(9), 1–5.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

16

ACTIVITY 4.3:

How Do You Know You Won’t Like It, If You Don’t

Try a Little?

When you were a small child, did your parents ever try to get you to eat something that you were

convinced you wouldn’t like? Why did you think you wouldn’t like it? Did you actually like it,

or did your preconceptions make it taste awful? Do you know people who seem to enjoy what

you consider terrible-tasting foods (such as Limburger cheese or single-malt scotch whiskey),

just because they’re high-status foods?

Some psychologists suggest that our expectations can actually change our sensory experiences.

For instance, Rozin, Fallon, and Augustini-Ziskind (1985) and Rozin and Fallon (1987) note that

even though children might like certain foods, they begin to find them disgusting after they’ve

come into contact with some other food that they find disgusting. Ratings of wines also seem to

be heavily influenced by expectations (Friedman & Fireworker, 1977). In fact, expectations

about the quality of a wine were found to influence diners’ enjoyment and evaluation of the

quality of an entire meal, and how much of that meal they actually eat (Payne & Wansink, 2007;

Wansink, Payne, & North, 2007). Taste experiments on beer (Lee, Frederick, & Ariely, 2006)

and soups (Prescott & Young, 2002) also showed that expectations had a major impact on flavor

ratings.

Is this a real effect, or is something else going on? Use the critical thinking method to come to

your own conclusion about whether preconceptions change our sensory experiences. Be sure to

support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you

need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Friedman, H. H., & Fireworker, R. B. (1977). The susceptibility of consumers to unseen

group influences. Journal of Social Psychology, 102, 155–156.

Lee, L., Frederick, S., & Ariely, D. (2006). Try it, you=11 like it: The influence of

expectation, consumption, and revelation on preferences for beer. Psychological

Science, 17, 1054–1058.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

17

Payne, C., & Wansink, B. (2007). How wine expectations influence meal evaluations and

consumption. FASEB Journal, 21(5), 327.

Prescott, J., & Young, A. (2002). Does information about MSG (monosodium glutamate)

content influence consumer ratings of soups with and without added MSG? Appetite,

39(1), 25–33.

Rozin, P., & Fallon, A. (1987). A perspective on disgust. Psychological Review, 94, 23–41.

Rozin, P., Fallon, A., & Augustoni-Ziskind, M. (1985). The child’s conception of food: The

development of contamination sensitivity to “disgusting” substances. Developmental

Psychology, 21, 1075–1079.

Wansink, B., Payne, C., & North, J. (2007). Fine as North Dakota wine: Sensory

expectations and the intake of companion foods. FASEB Journal, 21(5), 329.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

18

CHAPTER

5

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 5.1:

Multitasking Makes Life Easier

Have you ever watched someone driving while talking on a cell phone, drinking a cup of coffee,

and chatting with people in their car? Have you ever tried to study while also watching

television, listening to something on your MP3 player, snacking, checking your e-mail, and

talking to someone on the telephone? Many people believe that doing many things at once is far

more efficient than doing one thing at a time. Articles in the popular press and some industry

journals tell us that multitasking is not only necessary and useful (Booth, 2004; Overholt, 2002),

but that it can enhance our working lives (Cook, 2005). Others talk about the dangers of

multitasking in terms of driving safety (Peters & Peters, 2002), productivity (Davidson, 2006),

and learning (Baddeley, Lewis, Eldridge, & Thomson, 1984; Blume, 2001). Still others

(Greenwald, 2004; Wasson, 2004) discuss potentially good and bad aspects of the behavior.

Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion about the utility of

multitasking. Does it help people become more effective and efficient? Be sure to support your

thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer

the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Baddeley, A., Lewis, V., Eldridge, M., & Thomson, N. (1984). Attention and retrieval from

long-term memory. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 113, 518–540.

Blume, H. (2001). Mnemonic plague. American Prospect, 12(14), 39–41.

Booth, J. E. (2004). The art of juggling. Association Management, 56(5), 69.

Cook, P. (2005). Women in the workplace. Chemistry & Industry, 1, 12–13.

Davidson, J. (2006). Why multitasking backfires. Associations Now, 2(6), 14.

Greenwald, A. G. (2004). On doing two things at once: IV. Necessary and sufficient

conditions: Rejoinder to Lien, Proctor, and Ruthruff (2003). Journal of Experimental

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

19

Psychology: Human Perception and Performance, 30, 632–636.

Overholt, A. (2002). The art of multitasking. Fast Company, 63, 118–125.

Peters, G. A., & Peters, B. J. (2002). The distracted driver: How dangerous is

“multitasking”? Professional Safety, 47(3), 34–40.

Wasson, C. (2004). Multitasking during virtual meetings. Human Resource Planning, 27(4),

47–60.

ACTIVITY 5.2:

Racial Profiling and National Security

In recent years, there has been a major thrust to identify and capture suspected terrorists before

they can do any harm to the public. Newspaper columnists such as Nicolas Kristof (2002) have

called for racial profiling to assist in this effort. Yet as both the New York Times (“The New

Airport Profiling,” 2003) and Newsweek (Begley et al., 2001) note, profiling may not be a

successful strategy. Yetman (2004) seems to argue that profiling may be helpful, and that it will

occur, in any case. Grimland, Apter, and Kerkhof (2006) argue that the number of factors

influencing suicide bombers suggests that they cannot be profiled successfully. Complicating this

debate is America’s stated support for equality and the possible conflict between profiling and

the civil liberties of the targeted people.

Is the use of racial or ethnic profiling effective in identifying possible terrorists? Use the critical

thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible

source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following

questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Begley, S., Clemetson, L., Rogers, A., Levy, S., McGrath, P., Chen, J., & Underhill, W.

(2001, October 1). As America vows ‘never again,’ it is launching a series of

antiterrorism measures—from ethnic profiling to snooping through your personal email. Newsweek, 138(14), 58–62.

Grimland, M., Apter, A., & Kerkhof, A. (2006). The phenomenon of suicide bombing:

A review of psychological and nonpsychological factors. Crisis: The Journal of Crisis

Intervention and Suicide Prevention, 27(3), 107–118.

Kristof, N. D. (2002, May 31). Liberal reality check: When racial profiling works [Editorial].

New York Times, 151(52135), p. A25.

The New Airport Profiling. (2003, March 11). [Editorial]. New York Times, 152(52419),

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

20

p. A28.

Yetman, J. (2004). Suicidal terrorism and discriminatory screening: An efficiency-equity

trade-off. Defence and Peace Economics, 15, 221–230.

ACTIVITY 5.3:

The Roller Coaster of Love

What makes us fall in love? Why does one person completely bowl us over, while others make

no impression at all? Is it fate, or is it something much simpler? Some psychologists suggest that

it might be a phenomenon called excitation transfer, which is “the process of carrying over

arousal from one experience to an independent situation” (Bernstein, Penner, Clarke-Stewart, &

Roy, 2008, p. 447). For example, if you’ve just finished working out and an attractive person

smiles at you, you’re likely to think that it’s his smile that’s making your heart pound, so you’re

likely to have a much stronger emotional reaction than you would have if you’d met him when

you were relaxed and just sitting around.

Evidence supporting this position has been posited by several researchers (Lewandowski &

Aron, 2004; Meston & Frohlich, 2003; Walsh, Meister, & Kleinke, 1977). In fact, McClanahan,

Gold, Lenney, Ryckman, and Kulberg (1990) found that even when people were dissimilar,

which usually results in dislike, transferred excitation would result in attraction.

Cotton (1981) disagreed, suggesting that the evidence is not convincing, and that there may be

other explanations. Meston and Frohlich (2003) reported that although excitation transfer was

strong with non-romantic partners, it wasn’t if the people being tested already had an ongoing

romantic relationship with each other. Other psychologists feel that other factors such as

perceived similarity (Jones, Pelham, Carvallo, & Mirenberg, 2004; Montoya & Horton, 2004),

the influence of friends (Graziano, Jensen-Campbell, Shevilske, & Lundgren, 1993), and

physical beauty (Maner et al., 2003) might have considerably more influence on possible

romantic feelings. Robert Baron (1987) even found evidence for the influence of negatively

charged ions in the environment.

What is the truth? Is transferred excitation as influential in stirring romance as some might

suggest? Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support

your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to

answer the following questions:

1. What am I being asked to believe or accept?

2. What evidence is there to support the assertion?

3. Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

21

4. What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

5. What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Baron, R. A. (1987). Effects of negative ions on interpersonal attraction: Evidence for

intensification. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 52, 547–553.

Bernstein, D. A., Penner, L. A., Clarke-Stewart, A., & Roy, E. J. (2008). Psychology (8th

ed.). Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Cotton, J. L. (1981). A review of research on Schachter’s theory of emotion and the

misattribution of arousal. European Journal of Social Psychology, 11, 365–397.

Graziano, W. G., Jensen-Campbell, L. A., Shebilske, L. J., & Lundgren, S. R. (1993). Social

influence, sex differences, and judgments of beauty: Putting the interpersonal back in

interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 65, 522–531.

Jones, J. T., Pelham, B. W., Carvallo, M., & Mirenberg, M. C. (2004). How do I love thee?

Let me count the Js: Implicit egotism and interpersonal attraction. Journal of

Personality and Social Psychology, 87, 665–683.

Lewandowski, G. W., & Aron, A. P. (2004). Distinguishing arousal from novelty and

challenge in initial romantic attraction between strangers. Social Behavior and

Personality, 32, 361–372.

Maner, J. K., Kenrick, D. T., Becker, D. V., Delton, A. W., Hofer, B., Wilbur, C. J., &

Neuberg, S. L. (2003). Sexually selective cognition: Beauty captures the mind of the

beholder. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85, 1107–1120.

McClanahan, K. K., Gold, J. A., Lenney, E., Ryckman, R. M., & Kulberg, G. E. (1990).

Infatuation and attraction to a dissimilar other: Why is love blind? Journal of Social

Psychology, 130, 433–445.

Meston, C. M., & Frohlich, P. F. (2003). Love at first fright: Partner salience moderates

roller-coaster-induced excitation transfer. Archives of Sexual Behavior, 32, 537–544.

Montoya, R. M., & Horton, R. S. (2004). On the importance of cognitive evaluation as a

determinant of interpersonal attraction. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

86, 696–712.

Walsh, N. A., Meister, L. A., & Kleinke, C. L. (1977). Interpersonal attraction and visual

behavior as a function of perceived arousal and evaluation by an opposite sex p erson.

Journal of Social Psychology, 103, 65–74.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

22

CHAPTER

6

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 6.1:

Hypnopædia (“Sleep Learning”)

According to the dictionary (Hypnopedia, 1987), hypnopædia is “A method of teaching in which

information heard while the learner is asleep is supposed to be retained (p. 831).” The term was

first used by Aldous Huxley (1932) in his novel Brave New World. Imagine learning everything

you need to know for this psychology course by hearing recordings of the textbook and accounts

of exciting experiments read to you each night by Dr. Bernstein. Each morning, you would

awaken with a new store of information, which you would be able to use on later examinations,

and later in life as you need to solve psychologically based problems. It sounds too good to be

true. Is it?

Almost as soon as the idea was issued, psychologists became interested in testing it. Leshan

(1942) found that hypnopædia helped people stop biting their nails. Some researchers (Fox &

Robbin, 1952) reported that subjects actually learned information during sleep. Other researchers

(Simon & Emmons, 1955; Simon & Emmons, 1956) determined that any learning actually took

place during a waking state, not during actual sleep. In his review of the literature on

hypnopædia, Aarons (1976) found several anomalies in the various studies which might have

accounted for the differing results and called for more controlled experimentation. The debate is

still raging.

Is hypnopædia effective? Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be

sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically,

you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Aarons, L. (1976). Sleep-assisted instruction. Psychological Bulletin, 83, 1–40.

Fox, B. H. & Robbin, J. S. (1952). The retention of material presented during sleep. Journal

of Experimental Psychology, 43, 75–79.

Huxley, A. (1932). Brave New World, London: Chatto & Windus.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

23

Hypnopedia. (1987). In The American Heritage Illustrated Encyclopedic Dictionary. Boston:

Houghton Mifflin.

Leshan, L. (1942). The breaking of a habit by suggestion during sleep. Journal of Abnormal

and Social Psychology, 37, 406–408.

Simon, C. W., & Emmons, W. H. (1955). Learning during sleep? Psychological Bulletin, 52,

328–342.

Simon, C. W., & Emmons, W. H. (1956). Responses to material presented during various

levels of sleep. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 51, 89–97.

ACTIVITY 6.2:

Never Change Answers on a Multiple Choice Test

Your teachers or parents have likely given you lots of advice about how to study and take tests.

One common piece of advice is that you should never change your answers on a multiple-choice

test, but should always go with your first “gut feeling” if in doubt. Several online sources

(Dummies.com, n.d.; Fat Campus Test Taking Strategies, n.d.; Test Taking Strategy from the

Editors at Campus Expert, n.d.) give this advice. However, not all students seem to take this

advice. According to several researchers (Ballance, 1977; Frederickson, 1999; McMorris &

Weidemann, 1986), most students change their answers.

But does it help? A good deal of research on changing answers has been done by psychologists

over the years. Matthews (1929), Reile (1952), Reiling and Taylor (1972), and Vispoel (2000)

are among many researchers who studied the success rates of students who changed answers on

tests.

Should you stick with your first impulse on multiple-choice tests? Use the critical thinking

method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source

material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Ballance, C.T. (1977). Students’ expectations and their answer-changing behavior.

Psychological Reports, 41, 163–166.

Dummies.com. (n.d.). Discovering test taking strategies for the GED. Retrieved on

January 15, 2007, from http://www.dummies.com/WileyCDA/DummiesArticle/

id-1753,subcat-TESTPREP.html?print=true.

Fat Campus Test Taking Strategies. (n.d.). Retrieved January 15, 2007, from http://

fatcampus.com/test.htm.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

24

Frederickson, C.G. (1999). Multiple-choice answer changing: A type connection? Journal of

Psychological Type, 51, 40–46.

Mathews, C.O. (1929). Erroneous first impressions on objective tests Journal of Educational

Psychology, 20, 280–286.

McMorris, R.F. & Weideman, A.H. (1986). Answer changing after instruction on answer

changing. Measurement & Evaluation in Counseling & Development, 19, 93–101.

Reile, P. J. (1952). Should students change their initial answers on objective-type tests? More

evidence regarding an old problem. Journal of Educational Psychology, 43, 110–115.

Reiling, E. & Taylor, R. (1972). A new approach to the problem of changing initial responses

to multiple choice questions. Journal of Educational Measurement, 9, 67–70.

Test Taking Strategy from the Editors at Campus Expert. (n.d.) Retrieved January 15, 2 007,

from http://www.campusexpert.com/test.htm.

Vispoel, W. P. (2000). Reviewing and changing answers on computerized fixed -item

vocabulary tests. Educational & Psychological Measurement, 60, 371–384.

ACTIVITY 6.3:

A Computer on Every Desk

Many parents, educators, and reporters believe that all children can benefit from having

computers at school (Bergin, Ford, & Hess, 1993; de Pommereau, 1997; Elliot, 2000). Some of

the advantages they describe are that students will become better writers by using word

processing software; will achieve better learning outcomes; will be more aware of current events

by being able to access a world of information on the Internet; will learn to communicate better

by using e-mail and instant messaging, and will become more equitable and cooperative. Others

believe that computers may not be as useful or helpful as some might hope, either because they

are less suitable for educational tasks (Attewell, Belkis, & Battle, 2003; Cunningham &

Stanovich, 1990; Toppo, 2006), because they will not be properly adopted by educators

(Reynolds, Treharne, & Tripp, 2003), or because they will not be accessible to children outside

of school (Selwyn & Bullon, 2000). Some feel that computer use will discourage students from

learning, from paying attention in class and from interacting with people; that computer use may

not be as effective as other teaching methods; and that using computers in school may harm

students socially and physically. Even early researchers noted that there were major issues to be

resolved before allowing computers to become part of children’s daily life in school (Lepper,

1985).

What do you think? Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion about

whether computers are beneficial in the classroom. Be sure to support your thoughts with

credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following

questions:

1. What am I being asked to believe or accept?

2. What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

25

3. Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

4. What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

5. What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Attwell, P., Belkis, S-G., & Battle, J. (2003). Computers and young children: Social benefit

or social problem? Social Forces, 82, 277–296.

Bergin, D. A., Ford, M. E., & Hess, R. D. (1993). Patterns of motivation and social behavior

associated with microcomputer use of young children. Journal of Educational

Psychology, 85, 437–445.

Cunningham, A., & Stanovich, K. E. (1990). Early spelling acquisition: Writing beats the

computer. Journal of Educational Psychology, 82, 159–162.

de Pommereau, I. (1997, April 21). Computers give children the key to learning.

Christian Science Monitor, 89(101), 11.

Elliot, I. (2000, April). A laptop in every backpack. Teaching PreK-8, 30(7), 40–43.

Lepper, M. (1985). Microcomputers in education: Motivational and social issues.

American Psychologist, 40, 1–18.

Reynolds, D., Treharne, D., & Tripp, H. (2003). ICT–the hopes and the reality. British

Journal of Educational Technology, 34, 151–167.

Selwyn, N. & Bullon, K. (2000). Primary school children’s use of ICT. British Journal of

Educational Technology, 31, 321–332.

Toppo, G. (2006, April 11). Computers may not boost student achievement. USA Today, 08d.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

26

CHAPTER

7

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 7.1:

Is Fish Really Brain Food?

For many years, people have believed that eating fish will help make you smarter and improve

your memory, referring to fish as “brain food” (Calon et al., 2004; Kirchheimer, 2004; Marano,

2004; Warner, 2004). Yet some researchers note that eating fish may cause memory problems

(Schantz et al., 2001).

Can you improve your memory by eating more fish or by taking supplements that contain fish oil

or other fish byproducts? Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be

sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically,

you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Calon, F., Lim, G. P., Yang, F., Morihara, T., Teter, B., Ubeda, O., Rostaing, P., Triller, A.,

Salem, N., Ashe, K. H., Frautschy, S. A., & Cole, G. M. (2004). Docosahexaenoic

acid protects from dendritic pathology in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model.

Neuron, 43, 633–645.

Kirchheimer, S. (2004, September 1). Why fish seems to prevent Alzheimer’s damage: Study

shows DHA in omega-3 fatty acid lowers Alzheimer’s disease risk. WebMD Medical

News. Retrieved from http://www.webmd.com/content/Article/93/102368.htm.

Marano, H. E. (2004, March 16). FoodnMood: Save your brain. Psychology Today. Retrieved

January 13, 2007, from http://www.psychologytoday.com/articles/

pto-20040316–000006.html.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

27

Schantz, S. L., Gassior, D. M., Polverejan, E., McCaffrey, R. J., Sweeney, A. M., Humphrey,

H. E. B., & Gardiner, J. C. (2001). Impairments of memory and learning in older

adults exposed to polychlorinated biphenyls via consumption of Great Lakes fish.

Environmental Health Perspectives, 109, 605–611.

Warner, J. (2004). Fish may protect brain from effects of aging: Fatty fish may help prevent

Alzheimer’s, but other fats raise risks. WebMD Medical News. Retrieved from

http://www.webmd.com/content/Article/80/96450.htm.

ACTIVITY 7.2:

Cramming for Success

One constant from grade school through post-graduate study is that students take many tests. To

pass them, you may have to learn a lot of information in a very short time. That’s not easy.

Because there are many demands on a student’s time, one strategy people may use is cramming.

This means that they study everything they need to know on the day before a test, so that it’s

fresh in their minds when they have to take the exam. In fact, they may study all night and into

the next day in order to read everything, usually using a rote memorization strategy. They may

also use specialized tools, such as flash cards or other study aids. In some cases, this works well.

Smart crammers may pass their examinations (Martel & Hemphill, 1996; Tigner, 1999). Others

say it does not work under most circumstances (Tigner, 1999). Miller’s (1956) work on the limits

of memory capacity may have some bearing. Some researchers report mixed results (Romano,

Wallace, Helmick, Carey, & Adkins, 2005). Researchers looking at long-term retention imply

that distributed practice, or spaced learning, tends to yield much better results (Conway, Cohen,

& Stanhope, 1992).

So, is cramming a good strategy for learning? Will people who cram for examinations be able to

retain the information and use it in productive ways? Use the critical thinking method to come to

your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with credible source material. Remember

that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Conway, M. A., Cohen, G., & Stanhope, N. (1992). Very long-term memory for knowledge

acquired at school and university. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 6, 467–482.

Martel, J. & Hemphill, S. (1996, October 17). Getting ahead: Upgrade now! Rolling Stone,

745, p. 113–116.

Miller, G. A. (1956). The magical number seven, plus or minus two: Some limits on our

capacity for processing information. Psychological Review, 63, 81–97.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

28

Romano, J., Wallace, T. L., Helmick, I. J., Carey, L. M., & Adkins, L. (2005). Study

procrastination, achievement, and academic motivation in web-based and blended

distance learning. Internet & Higher Education, 8, 299–305.

ACTIVITY 7.3:

A Healthy Mind in a Healthy Body

In 2001, Newsweek magazine reported that keeping physically fit helps us stay mentally fit

(Adler, Raymond, & Underwood, 2001). To this end, many people recommend lifelong sports

such as hiking, golf, or tennis that can be played well into old age (Brainy Hikers, 2005). They

believe that by engaging in these sports, you challenge yourself to think and remember things in

ways that promote good long-term memory and problem solving ability. However, not all sports

are helpful to all people. Christensen and Mackinnon (1993) note that certain types of physical

activity were linked to certain types of memory gains and task performance. Slosman and

colleagues (2004) report on the effects of scuba diving on memory, for example.

Use the critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion about whether engaging in

lifelong sports will help you retain your long-term memory. Be sure to support your thoughts

with credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the

following questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Adler, J., Raymond, J., & Underwood, A. (2001, Fall/Winter). Fighting back with sweat.

Newsweek, 138(11), 34–41.

Brainy Hikers. (2005, July/August). Backpacker, 33(6), 60.

Christensen, H., & Mackinnon, A. (1993). The association between mental, social and

physical activity and cognitive performance in young and old subjects. Age and

Ageing, 22, 175–182.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

29

Slosman, D. O., de Ribaupierre, S., Chicheriao, C., Ludwig, C., Montandon, M.-L., Allaoua,

M., Genton, L., Pichard, C., Grousset, A., Mayer, E., Annoni, J.-M., & de

Ribaupierre, A. (2004). Negative neurofunctional effects of frequency, depth and

environment in recreational scuba diving: The Geneva “memory dive” study. British

Journal of Sports Medicine, 38, 108–114.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

30

CHAPTER

8

CRITICAL THINKING ACTIVITIES

ACTIVITY 8.1:

Children’s Books: Big Words or Little Words?

Many parents and teachers believe that children’s stories should contain simple language,

appropriate to the level of a beginning reader. They feel that if a child encounters too many

difficult or unfamiliar words, the child will become discouraged and will not want to read. This

was the idea behind basal readers, many of which are simplified versions of other stories. In fact,

after an extensive review of the available basal readers, Hill (1997) described basal readers as

excellent resources for learning language at an accessible level. Farr (1988) also extols the value

of the basal readers. Ohanian (1987), however, feels that children benefit from more complex

words and syntactic structures, and that children’s stories should contain more intriguing words

and sentences. Sakari (1996) analyzed basal versions of children’s stories to see how well their

original meanings came through. Other teaching methods have also been compared to the use of

basal readers by several researchers (Popplewell & Doty, 2001).

Do you believe that children’s books should be written at an extremely simple level? Use the

critical thinking method to come to your own conclusion. Be sure to support your thoughts with

credible source material. Remember that in thinking critically, you need to answer the following

questions:

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

What am I being asked to believe or accept?

What evidence is there to support the assertion?

Are there alternative ways of interpreting the evidence?

What additional evidence would help to evaluate the alternatives?

What conclusions are most reasonable?

References:

Farr, R. (1988). Reading: A place for basal readers under the whole language umbrella.

Educational Leadership, 46(3), 86.

Green, G. M., & Olsen, M. S. (1986). Preferences for and comprehension of original and

readability-adapted materials. (Technical Report No. 393). Washington: National

Institute of Education.

Hill, D. R. (1997, May 23). Graded (basal) readers—choosing the best. The Language

Teacher Online. Retrieved from http://www.jalt-publications.org/tlt/files/97/may/

choosing.html.

Ohanian, S. (1987, September). Ruffles and flourishes. The Atlantic Monthly, 260(3), 20–21.

Copyright © Houghton Mifflin Company. All rights reserved.

31

Sakari, M. D. (1996). Altering trade books to “fit” literature-based basals. (ERIC Document

Reproduction Service No. ED396239).

ACTIVITY 8.2:

It’s Just Going Around Right Now

Diagnosing an illness is a form of problem solving. If you watch any episode of the show House

(e.g. House’s New Staff, n.d.), you’ll see Dr. Gregory House and his team use differential

diagnoses to determine the particular diseases or conditions of their patients. Doctors do this by

listing every disease or condition that explains a patient’s symptoms, and then trying to figure

out which particular condition she has through a process of elimination. They are trained to do

this in medical school, much as clinical psychologists are in their graduate programs. In fact,

differential diagnosis is a good example of critical thinking.

Of course, doctors are human, and often take cognitive shortcuts rather than engaging in the

entire process of differential diagnosis. After all, they’re experts, and their experience should

help them cut through a lot of the tedium of working through such a long and involved process.

Researchers suggest that experts use such shortcuts because of their superior knowledge base and