Prof. Ronald W. Pruessen - International Institute for Peace

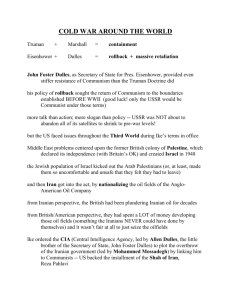

advertisement

SYMPOSIUM: MOSKAUER MEMORANDUM 1955 – SIGNAL FÜR DEN FRIEDEN IN EUROPA Prof. Ronald W. Pruessen “The United States and the Moscow Memorandum” Introduction: From the vantage point of the United States, the Moscow Memorandum of April 15, 1955 – and the Austrian Peace Treaty signed a month later – both fit into a complex story of shifting policies and conflicted impulses. It is a story that includes stern resistance to any relaxation of Cold War tensions as well as exhilaration about prospects for “détente” or “thaw.” It is a story that zigzags between stubbornness and flexibility and between serious negotiation and a reliance on pressure tactics. Let me try to suggest some of the complexities of American behaviour by sketching in four layers or facets. Given Vienna’s importance to the story, in fact, let me use a musical analogy and suggest that American thinking and policies went through four movements. I don’t want to suggest that there was anything like symphonic beauty to what emerged – I’ll actually suggest something quite far from that – but the notion of an evolving symphonic form may be helpful in briefly communicating variations on a theme. I’ll even give the movements a touch of musical identity – an identity designed to suggest some of the political or diplomatic or even psychological texture of the historical experiences. I. I’ll begin with a movement characterized by American pessimism and negativism. This might be seen as a movement in the style of Alban Berg – in the spirit, at least, of Wozzeck: harsh atonality and dissonance, suggesting an air of crisis and even irrationality. Like some symphonic first movements, this one is long. For the American actors important to Austrian developments in 1955, it might actually be said to have lasted two years or more – going back at least to Dwight Eisenhower’s victory in the 1952 presidential election. Eisenhower was elected at a time when Americans believed an escalating Cold War had placed them in great danger. Harry Truman had not only failed to win the war in Korea, for instance, but had been unable to generate a negotiated armistice. The Soviet Union, on the other hand, had ended an American monopoly on atomic weapons – and had found a major new ally in the People’s Republic of China. Eisenhower eventually developed a reputation for grandfatherly congeniality, but his 1952 election owed more to the fact that he was General Eisenhower and that the military hero who had been a key architect of victory in World War II was promising to lead a vigorous new war on communism. In the early stages of his presidency, he took strong steps in exactly this direction: he named the stern John Foster Dulles as his secretary of state; he threatened to use nuclear weapons in Korea if Beijing did not sign an armistice agreement; he authorized coups against governments in Iran and Guatemala. Eisenhower – and Dulles – also certainly resisted any easing of direct bilateral relations with Moscow. Some world leaders saw Joseph Stalin’s death (in March 1953) as an opportunity to Informationen zum Symposium, den Teilnehmern und unserem Institut entnehmen Sie bitte unserer website: www.iip.at 1 SYMPOSIUM: MOSKAUER MEMORANDUM 1955 – SIGNAL FÜR DEN FRIEDEN IN EUROPA explore possibilities for détente. Winston Churchill tried again and again to sell Eisenhower on the idea of a “summit” conference. But Washington would have none of it in 1953 and 1954. At a meeting with Churchill in Bermuda, Eisenhower said that the Soviet Union had to be treated like “a woman of the streets”: Despite a new dress, “despite bath, perfume or lace, it was still the same old girl” – and one hardly worthy of a summit embrace. II. American thinking began to change in the spring of 1955, bringing a new stage in the evolution I am suggesting. It was a stage – a movement – characterized by a sense that the thick ice of the Cold War might actually thaw. To return to my notion of musical characteristics, I’d suggest that high-level attitudes in Washington went from the harshness of Alban Berg to the mellowness of Beethoven in seriously relaxed mode: the first movement of the Sixth Symphony comes to mind (“Awakening of joyous feelings upon arrival in the country”). Austrian developments played a very important role in producing a new movement. Eisenhower and Dulles were struck by what they saw as several meaningful shifts in Soviet behaviour: They were impressed by Moscow moves to improve relations with both Japan and Tito’s Yugoslavia – and by the fact that the Kremlin did not manufacture a crisis as arrangements were finalized for the re-armament of West Germany. But nothing prompted more optimistic speculation about détente than Moscow’s strategy shifts concerning Austria – the shifts which generated the Moscow Memorandum of April 15. CIA Director Allen W. Dulles described “this Soviet move vis-a-vis Austria as the most significant since the end of World War II.” His brother, John Foster Dulles, agreed: “Moscow’s reasonable attitude may actually foreshadow a quite different Soviet long-term policy, both as regards Europe and the Far East.” American leaders did not shift casually from stubborn cynicism into optimism. If they were positively impressed, it was because they thought they understood why a real change in Moscow’s behaviour seemed to be underway – and because they thought the reasons made good sense. On one hand, for example, Eisenhower and Dulles saw Stalin’s successors as learning lessons. After “buck[ing] hard against the ramparts of the free world” for so long, the secretary of state said, “they might now deem it more convenient to conform slightly to a world situation that they have found that they cannot otherwise change.” A key learning experience in this respect had been Moscow’s inability to prevent West German rearmament: as Dulles put it, the Soviets had “put everything they had into that policy and it failed.” On another hand, Washington leaders also believed that such a lesson had been greatly reinforced by the Soviet Union’s economic difficulties. As Eisenhower and Dulles saw it, Moscow was “desperately looking for a respite” in the arms race with the United States – an arms race that they had found was “much too expensive.” The Soviet Union “was trying to match U.S. military power with an industrial base only one-third or one-fourth that of the U.S.” and “The whole Communist system was overextended as a result.” To compound the problem, the Kremlin’s satellite clients were making heavy demands for military and economic assistance and were “squirming” as the limits of Soviet resources became apparent: “The Russians,” Dulles said, “believe that they must do something in order to raise consumption levels for the populations of the Soviet Union and the satellites.” The delineation of such pressures and problems led American policy makers to believe that developments like the Moscow Memorandum were not some new example of Soviet trickery. Eisenhower finally accepted the idea that a “summit” meeting was a worthwhile enterprise – and John Foster Dulles actually began to speculate glowingly about what might be achieved there. As Informationen zum Symposium, den Teilnehmern und unserem Institut entnehmen Sie bitte unserer website: www.iip.at 2 SYMPOSIUM: MOSKAUER MEMORANDUM 1955 – SIGNAL FÜR DEN FRIEDEN IN EUROPA he put it in the spring weeks following the Austrian breakthrough, “…the Soviets had effected a complete alteration of their policy. Their policy had been hard and was becoming soft. The Iron curtain is going to disappear….we were now confronting a real opportunity…for a rollback of Soviet power. Such a rollback might leave the present satellite states in a status not unlike that of Finland.” III. Optimism is not usually seen as a characteristic of American foreign policy in the 1950s – but it was there in the spring of 1955. Nor is openness to negotiations usually associated with a policy maker like John Foster Dulles – particularly negotiations of the kind that require flexibility, imagination, and (one might say) genuine “diplomacy.” But openness to genuine diplomacy was evident in the spring of 1955 – enough to suggest that serious preparations for negotiations should be seen as a third movement in the story of American responses to the Moscow Memorandum. Thinking musically again, by the way, I would propose that this third movement saw a shift from Beethoven’s pastoral mood to Gustav Mahler-like moments: I’m thinking of Mahler’s sometimes very supple woodwinds – as with the sinuous oboes and clarinets in the First Symphony. Whatever their reputations, Eisenhower and Dulles were capable of flexibility and diplomacy. It is often said, for example, that the president had been a brilliant diplomat in preparing for the Normandy invasion – managing prima donnas in both British and American quarters. For his part, Dulles had spent forty years as an enormously successful international lawyer before becoming secretary of state – and the creative negotiation of complex business and financial agreements had made up the lion’s share of his work. A capacity for flexibility and diplomacy was certainly evident in the spring of 1955. The agreement to hold a “summit” conference in July was never seen as simply a public relations maneuver, for example: the Austrian Peace Treaty spurred conviction that other breakthroughs might also be negotiated. Eisenhower and Dulles were particularly interested in seeing whether the design of some all-European security package might provide the context for progress on German reunification. With Eden in London, Dulles turned his mind to creative possibilities. “We might eventually get German unification within the framework of an agreement about levels of forces in Europe,” he said, with “the forces on both sides…thinned out towards the area of contact.” In a phone conversation with his brother at the C.I.A., for example, Dulles said: “…he has this sort of plan – he doesn’t know if it is any good – that we should propose to the Russians that they should take an area of comparable size, etc., to our Western European area and match us with troops, etc.” When Allen Dulles asked for the approximate dimensions of the area being considered, the secretary of state said “roughly speaking, if you took in the East the area comparable in size to the Brussels Pact area, it would cover most of the satellites and Russia back to Minsk.” IV. To say that Eisenhower and Dulles were capable of flexibility and diplomacy is not to say that they consistently or adequately chose to use their capabilities. In fact, my story today needs a concluding fourth movement because both the president and the secretary of state were also subject to other clearly conflicting impulses. Eisenhower and Dulles definitely thought about the potential rewards of compromise and détente – and they definitely mapped some detailed paths that might have led them in that direction – but they were ultimately seduced by harder line calculations. Informationen zum Symposium, den Teilnehmern und unserem Institut entnehmen Sie bitte unserer website: www.iip.at 3 SYMPOSIUM: MOSKAUER MEMORANDUM 1955 – SIGNAL FÜR DEN FRIEDEN IN EUROPA The most important countervailing force in the spring of 1955 was a thirst for rapid victory in the Cold War – as opposed to an appetite for a gradual relaxation of tensions by way of negotiation. The alternative line of reasoning went something like this: If the Kremlin was becoming more accommodating because of its economic weaknesses or diplomatic failures, for example – if these had produced developments like the Moscow Memorandum on Austria – wouldn’t it make more sense to keep applying pressure rather than relaxing it? As Dulles put it just days before the Geneva Summit Conference, “We have come such a long way by being firm, occasionally disagreeably firm, that I would hate to see the whole edifice undermined in response to a smile….[W]e are in the situation of being prepared to run a mile in competition with another runner whose distance suddenly appears to be a quarter mile. At the quarter mile mark, the Russian quarter miler says to the American miler, ‘This is really a quarter mile race, you know, and why don’t we call it off now?” Sufficient determination and firmness might yield a defeat of the Soviet Union, it was felt, not just its moderation. As the Joint Chiefs of Staff summarized the guiding principle just before the Geneva Summit, “the U.S. approach should be based on the view that…the Soviet Union was weakening and that we should accordingly hold its feet to the fire.” This proved to be so tempting a vision that the emphasis in American planning after the Austrian breakthrough shifted from the devising of negotiating strategies to the conceptualization of pressure tactics. Eisenhower and Dulles came to see Eastern Europe as an especially useful tool for compounding Moscow’s problems. By agreeing to unfreeze the Austrian situation, Dulles argued, “the Soviets may be loosing forces in the satellites which they would be unable to control.” To make the Kremlin’s task even harder, Washington would mount what it called “psychological warfare” campaigns to encourage further agitation of Eastern European populations. Radio Free Europe broadcasts and the dropping of leaflets from fly-over balloons, for example, would urge freedom for the satellites. U.S. effort also went into so-called “covert operations” – initiatives that were at least partially responsible for the bloody tale that unfolded in Budapest in 1956. By the way, I am aware that I have not yet suggested a musical character for this fourth movement in the progression of American thinking. Let me do that now – and suggest that Beethoven’s joy at the onset of spring and Mahler’s sinuous woodwinds gave way, in the end, to Anton Bruckner. I am thinking here of Bruckner’s love for blasts of brass – trumpets, especially: think about the first movement of the Fourth Symphony or the Te Deum. Those awesome, sometimes hair-raising moments in Bruckner capture well what came to be the American emphasis on power and pressure. It was as if Eisenhower and Dulles saw themselves outside the walls of Jericho, with the capacity to blow their ram horns forcefully enough to make the walls come tumbling down. But the walls of the satellite system did not fall down in 1955, of course – nor did they fall for decades after. The Cold War neither “thawed” nor ended. Austria alone, it might be said, enjoyed meaningful results after the Moscow Memorandum raised hopes high in April 1955. This certainly deserves celebration – here and on other occasions – but we should also be conscious of 1955’s more plentiful failures. Americans always blamed Moscow for foiling “détente” opportunities. And yet, without doubting at all that Soviet behaviour could be problematic, I would say it is also clear that the United States itself bears a real share of the responsibility for failure. Intoxicated by a dramatic vision of victory, Washington never really gave serious negotiation a chance in 1955. It never Informationen zum Symposium, den Teilnehmern und unserem Institut entnehmen Sie bitte unserer website: www.iip.at 4 SYMPOSIUM: MOSKAUER MEMORANDUM 1955 – SIGNAL FÜR DEN FRIEDEN IN EUROPA really tried to execute a more moderate strategy aimed at takings small steps toward détente – steps like beginning the thinning out military forces in Central Europe or the beginning of minimal interaction across the German divide. (Both of these possibilities were discussed in Washington, but never pursued.) The Moscow Memorandum should have served as a key example of the way patience, flexibility, diplomacy, and opportunity could combine to yield progress. Instead, Washington gave up the pursuit of modest possibilities in order to chase exhilarating visions that proved unattainable. This failure of what might be called real vision was the product of several forces. On one hand, Americans operated with a seriously flawed understanding of the Soviet Union. Although they recognized that Moscow was ready to explore new diplomatic routes in 1955, Eisenhower and others over-estimated Soviet weakness and desperation. It did not seem to occur to them that the Kremlin might be able to choose to wait for another day when their adversaries responded to the Austrian breakthrough with an offensive campaign in Eastern Europe – or that radio broadcasts, balloons, and covert operations would not eliminate the Kremlin’s capacity for brutal control of its satellites. On the other hand, American leaders in 1955 do not seem to have understood themselves very well either. As they sought Cold War victory through the application of pressure, Eisenhower, Dulles, and others failed to appreciate the way their dreams did not match their capabilities – failed to appreciate the arrogance of their expectations. Conclusion Let me conclude by saying that the weaknesses I am associating with American behaviour in 1955 remained evident through all of the fifty years that have passed since then. A failure to understand adversaries; a failure to match objectives with capabilities; a failure to tame arrogance when contemplating a choice between something and everything: surely this is not the first time you have heard someone point to such characteristics in American thinking and American foreign policy. They do not tell the whole story – but the story is very incomplete without them. Decades of involvement in Vietnam bring the characteristics to mind again and again, for example. And before, during, and after the painful Vietnam years, they are relevant to Washington’s choices with respect to issues as diverse as Cuba and China. And Iraq? Isn’t it especially disturbing to see how the present day brings us the most extreme of all examples of the failure to develop subtle analysis and effective diplomacy? Has there been a cohort of American policy makers more infatuated with arrogant posturing and pressure tactics than the present Bush administration? (Wouldn’t some Bruckner provide a perfect musical score for “Shock and Awe”?) Where Eisenhower and Dulles at least experienced a tug of war between alternative impulses – even if they then gave in to a desire for total victory or pressure as opposed to diplomacy – what can we make of leaders who seem to engage in no internal debate, who seem self-righteously convinced that there is only one way to proceed? There have been high prices to pay for such a mindset in the past. It is not pleasant to contemplate such questions on a celebratory occasion like this one – but it is also difficult to ignore them. Informationen zum Symposium, den Teilnehmern und unserem Institut entnehmen Sie bitte unserer website: www.iip.at 5