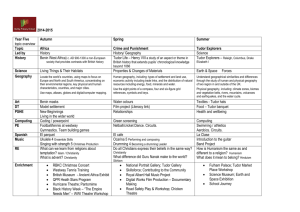

Tudor Pack - Nottingham Castle

advertisement

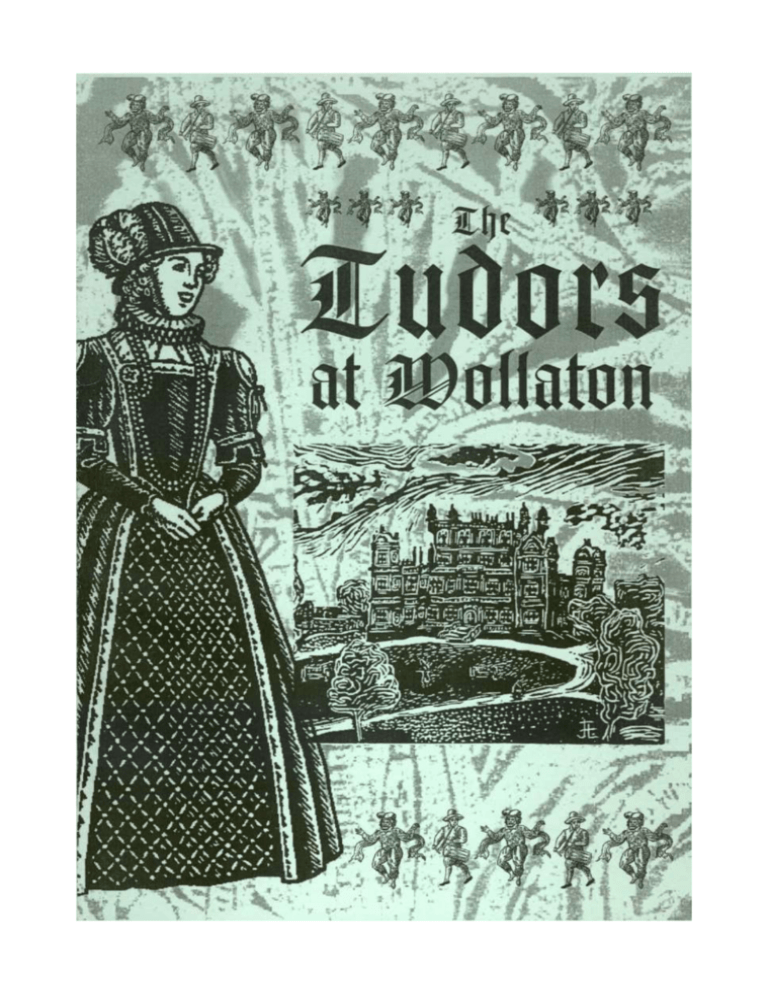

Contents The Tudor Age Tudor Time line Stuart Time Line A Tudor Christmas Tudor Food Tudor Recipes A Taste of the Past Clothes Examples of Tudor Costume Music & Dance Dances at Tudor Courts Songs and tunes Games and Pastimes Tudor Nottingham The Willoughbys of Wollaton Sir Hugh Willoughby, explorer The Willoughby Family The Passport of Francis Willoughby The Naturalist 'Book of Games' Wollaton Hall An Investigation The Tudor Age The Tudor age was a time of great excitement and change: cultural innovation with the great plays of William Shakespeare, exploration with the voyages of discovery and religious upheavals. Kings and Queens were more powerful than they are today, although there were weak monarchs such as Edward VI and Lady Jane Grey who reigned only briefly. The Stuart age, like that of the Tudors, was a period of great change. When Queen Elizabeth died her cousin James VI of Scotland became the first Stuart king of England. During the Stuart reign events such as the Gunpowder Plot, the Great Plague and the Great Fire of London took place. The Pilgrim Fathers sailed in search of anew world and England was plunged into a Civil War which was to overthrow the King himself. This pack focuses on the evidence that Wollaton Hall provides of this very rich period. Everything in the pack relates specifically to the Tudor or Stuart activity days which are held at the Hall. It provides teachers with background information which can be used both in preparation for a visit and for follow-up work, thus making a visit to the Hall an integral part of the National Curriculum KS2. The pack draws on the Hall itself as one of the finest examples of Elizabethan architecture; on Francis Willoughby whose ambitions were fulfilled by the creation of Wollaton Hall and on aspects of the daily life of the period such as food, costume and pastimes. Included in the pack are contemporary recipes to create a Tudor banquet which can be eaten in the Great Hall. It gives details of Tudor games such as skittleswhich can actually be played in the Skittle Alley at Wollaton Hall. There is also the opportunity to learn the Pavan and other Tudor dances. 1503 TUDOR TIME LINE Leonardo da Vinci paints the Mona Lisa 1509 Henry VIII becomes King of England 1535 Henry VIII becomes 'Supreme Head of the Church of England' 1547 Edward VI crowned King of England 1553 Lady Jane Grey becomes Queen of England, briefly. 1553 Mary I crowned Queen of England 1558 Elizabeth I becomes Queen of England 1564 William Shakespeare is born 1577 Francis Drake sets sail around the world 1580 Construction of Wollaton Hall begins 1587 Mary, Queen of Scots is executed 1588 The Spanish Armada is defeated 1588 Wollaton Hall is completed 1596 Francis Willoughby dies 1603 STUART TIME LINE James VI of Scotland crowned James I of England 1605 The Gunpowder Plot is foiled 1616 William Shakespeare dies 1620 The Pilgrim Fathers sail to America in the Mayflower 1625 Charles I becomes King of England 1642 The English Civil War begins 1649 Charles I beheaded 1651 Oliver Cromwell becomes Lord Protector of the Commonwealth 1653 Francis Willoughby, naturalist, attends Cambridge University 1660 The Restoration of the Monarchy - Charles II crowned King 1665 The Great Plague kills many people 1666 The Great Fire of London destroys much of the city 1672 Francis Willoughby, naturalist, dies 1685 James II becomes King Since pre-Christian times people have held a winter festival. This was an opportunity to celebrate the end of winter and the coming of spring. Many of our customs and traditions date back to these times but it was not until the 4th century A.D. that Christmas was officially established. Rather than trying to abolish the pagan customs, the church simply adapted them, applying its own meaning to the old rituals. The celebration of 'Old Christmas' by the Tudors at court was the high point of the year. Henry VIII delighted in the extravagance of the festivities and Elizabeth I spent the season gambling with loaded dice. The decoration of houses with evergreens - a symbol of everlasting life - at Christmas is of pagan origin. In the 16th century it was believed that they would bring good luck during the winter months. Mistletoe was an important part of the Druid tradition and was often associated with human sacrifice. This is why mistletoe is never found within a church. The tradition of the yule log also dates from Pagan times. During the Tudor years its use in Christmas festivities was very significant. The huge log was ceremoniously hauled home on Christmas Eve. It was then burnt throughout the Christmas period.. The custom was that part of the log was kept until the following year; this kept the evil spirits away. The tunes - if not the words - of some our most popular carols were written by the Tudors, including Good King Wenceslas, Ding Dong Merrily on High and While Shepherds Watched. Initially they were not religious hymns but everyday songs passed down through the generations. However, by the Tudor period carols had adopted a more religious emphasis and had become songs of joy to be sung at Christmas time. A Tudor Christmas was a time for music making and dancing. Plays were also enjoyed, for example Shakespeare's Twelfth Night was first performed for Elizabeth I during Christmas in the year 1601. 'Mumming' was a popular activity; young men and women dressed up as each other and travelled around the local villages giving dancing displays and performing drama. They were usually rewarded with a gift of money or food. The play usually centred upon a hero such as St George. Many of the actors wore masks to keep their identity secret. This was supposed to bring good luck during Christmas. Games were popular during the Christmas celebrations. At court or in the homes of the nobility a Lord of Misrule was appointed to lead the company in fun and games during the holiday. It was his responsibility to ensure that everybody had a good time. Many of the games we enjoy today date back to this period, such as Hide and Seek, Blind Man's Bluff and Hunt the Slipper. Games such as Charades and Squeak Piggy Squeak were greatly enjoyed. Other sports at Christmas were wrestling in the churchyard and skating on frozen lakes. A central part of Christmas Day has always been the Christmas Dinner where all the family come together to celebrate. For the Tudors the choice of food was more limited. As there were no fridges or freezers planning ahead was essential. Meat was preserved by pickling in brine or by drying and smoking it. In Tudor households the meal included pork or maybe a huge Christmas pie made from a variety of birds. Turkey didn't become popular until the 18th century; goose was served to Elizabeth I when news came of the destruction of the Spanish Armada. On hearing the news she decreed that goose should be eaten at Christmas ever after. In the homes of the nobility venison, swans or peacocks were eaten. However, the boar's head was always considered to be the grandest dish of all. It was usually served on a silver platter surrounded by the herb rosemary. Another favourite in the noble houses was a suckling pig, basted with butter and roasted on a spit. The meats were eaten with bread. The ancestor of the modern Christmas pudding was the plum porridge, a mixture of meat, broth, raisins and spices. When the porridge was made at home every member of the household was expected to make a wish whilst waiting taking a turn to stir the mixture. Over the years the porridge became so thick that it was renamed Christmas Pudding. The tradition of eating mince pies was already well established in the 16th century. The ingredients were more varied than they are today, for example chicken was often included. The mixture was put into small pastry cases called 'coffins'. According to tradition one was to be eaten on each of the twelve days of Christmas. Gingerbreads were also eaten, often in the shape of Christmas characters. For ordinary people the choice of food in the 16th century was limited. The main food was meat, usually pork, which was made into bacon, sausages and blood pudding. This was accompanied by bread, often made at home. Fish was also eaten; for the poor this meant salted or pickled herrings. The fish was prepared in this way to preserve it while it was brought inland. For those who lived on the coast there was more choice with oysters and whelks. Milk was used to make butter and cheese but only drunk by children whilst the adults drunk ale. Fruits such as apples and pears were eaten and were often baked. Many people were wary of eating vegetables, fearing they would cause illness, and so they were not eaten by the majority of ordinary people. The diet of the aristocracy was based on the same foods as that of the poor but was more varied with meats such as veal and pheasant. The wealthy had the choice of sea fish, including haddock and plaice, and many landowners had their own fish ponds containing carp. As well as baked fruits, the nobility ate sweetmeats and jellies for dessert and drank wines as well as ale. An interesting insight into the diet of a country gentleman is gained from the accounts of William Darrel, a Wiltshire squire, written in 1589 'Beef and mutton are the staple dishes at both dinner and supper with side dishes of rabbit, pheasant and sometimes veal Bread and beer are always available and often butter and cheese as well Soup is rarely eaten and the only vegetables are peas. Fishy for example herrings and plaice, is normally eaten on Fridays following the tradition established by the Catholic church For sweet there is a selection of jellies and sweetmeats but the gentleman prefers strawberries and cream. The cost of each meal ranges from five to ten shillings'. ("Life in Elizabethan England', A. Dodd 1961) As a result of the voyages of discovery new foods were introduced into England. These included fruits from Southern Europe such as quinces, apricots and red currants. Dried fruits, including raisins and dates, were also imported but, because of the expense, ordinary people only ate them at Christmas. Many vegetables were introduced from South America such as tomatoes (or 'love apples') from Mexico, kidney beans from Peru and potatoes from Chile. It would be years, however, before these were consumed on a large scale. Sugar was being imported in increasing quantities from the Caribbean. It was used to prepare sweetmeats, crystallised fruits and syrup. Although more sugar was being eaten in England, the majority of this was consumed by the aristocracy and not the poor. The consequence of eating more sugar was tooth decay. Queen Elizabeth I suffered from this and had black teeth. There were numerous remedies for tooth decay, such as rubbing powdered alabaster over the teeth. Nitric acid was also used to bleach the teeth but it often had disastrous results such as the loss of teeth. As there were no fridges or freezers, meat had to be salted and preserved to keep it from going bad. Once preserved, meat was wrapped in cloth and stored in the pantry. Beef, pork and veal were all boiled. This was done in large copper vessels which were heated over open fires that could also be used for roasting. As the preserved meat was very salty, spices were used whilst cooking to improve the taste. the meat and gravy and a smaller hole for the salt. Drinking vessels The utensils used when preparing the meal were knives and spoons, wooden bowls and whisks made from bundles of blanched twigs. The 16th century saw the decline in the practice of eating food from trenchers. These were 'plates' made from four-day old wholemeal bread. Traditionally, after the meal they were gathered up and given to the poor. The trencher was replaced by a square wooden board which had a large central hollow for were made of silver and gold for the wealthy whilst the poor used horn beakers and leatherjacks. However, there was an increased use of earthenware cups. The meal was eaten using knives and spoons. The host would provide the spoons and each guest would bring his Prune tart 12oz (350g) prunes 4oz (1 OOg) fresh white bread crumbs Vizpt (275ml) red wine 1 tsp (5ml) cinnamon 1 tsp (5ml) ground ginger 4oz (1 OOg) sugar 1 tbls (15ml) rose water Tudor recipes 3 tbls (45ml) water 2 egg yolks 2 tbls (30ml) rose water 2 tbls (30ml) sugar loz (25g) butter ground ginger and cinnamon to finish Peel, core and slice the apples and stew them in a covered heavy saucepan with the water until soft. Make the apples into a smooth puree by rubbing through a sieve or by using a blender. Return the puree to the saucepan, stir in the egg yolks and slowly heat to boiling point, stirring continuously. Pour the puree into a dish and allow to cool before serving. To finish, sprinkle with a little ground ginger and cinnamon. For the pastry: 3oz (75g) butter 4oz (1 OOg) plain flour 1 tsp (5ml) caster sugar 1 egg, beaten Soak the prunes overnight and then simmer in a little water for 10-15 minutes until tender. To make the pastry, rub the butter into the flour, mix in the sugar and slowly stir in the egg until it forms a soft dough which can be lightly kneaded with the hands. Roll out the pastry and use it to line an 8 inch (20cm) diameter, 2 inch (5cm) deep flan ring. Line the pastry with greaseproof paper, fill with uncooked haricot beans or crusts and bake blind at 425°F/220°C/Gas 7 for 15 minutes. Remove the beans and greaseproof paper. To make the filling, drain and stone the prunes and blend them with the remaining ingredients to form a thick smooth paste. Spoon the filling into the pastry case and return to the oven to bake at 350°F/180°C/Gas 4 for 1 lAt hours. Serve either hot or cold. A Book ofCookrye Very necessary for such as delight therin lV2lb (700g) apples A Proper Newe Book of Cokerye 2 eggs 4oz (lOOg) sugar 1 tbls (15ml) caraway or aniseed 6oz (175g) plain flour Beat the eggs in a 2 pint (1. lit) basin and then beat in the sugar, the aniseed or caraway and finally the flour, thus forming a stiff dough. Knead the dough on a lightly floured board and form into rolls approximately %inch (1 cm) by 4 inches (10cm) in length. Tie each of these into a simple knot and plunge them, five or six at a time, into a pan of boiling water, where they will immediately sink to the bottom. After a short time dislodge the knots from the bottom oi the pan with a spoon so that they float and swell for a minute or two. Then lift the knots out with a perforated spoon and allow them to drain on a clean tea towel laid over a wire rack. Arrange the knots on lightly buttered baking sheets and bake for 15 minutes at 350°F/ 180°C/Gas 4, then turn the knots over and return to the oven for 10-15 minutes until golden. Thomas Dawson: The Good Huswifes Jewell, pt.2 own knife. Although cutlery was used, the majority of people ate with their fingers, using the knife to divide the meat and the spoon to eat the gravy. Toothpicks were prized possessions and were often made from an aromatic wood such as rosemary. As meals were often eaten without cutlery, napkins were always needed. When not in use they were placed over the left shoulder. As lace collars were fashionable, it was customary to wear the napkin around the neck to protect the collar. In town dinner was normally at noon and supper at five, though this would be extended if the meal was a banquet. In the country supper was eaten earlier with harvesters and haymakers eating supper in the fields in the summer. Children ate separately but one of the sons would be brought in to salute the guests and to say Grace. It was customary for men to eat with their hats on but this practice declined in the 17th century. The Sovereign's food was publicly tested to ensure that the meal had not been poisoned. This was done as soon as the food was placed on the table. The test consisted of the server eating a piece of the food and drinking some of the soup. This ritual was performed even when the Sovereign was dining alone. There were developments concerning food in the 17th century, such as the new foods and the change of tableware, but these only affected the nobility. For the majority of the population little changed and most of the people continued to have a limited diet of meat, bread, cheese and fruit. If you book one of our Tudor activity days you will partake of your packed lunch as a banquet in the Great Hall. This is a chance to experience a Tudor meal so you will need to consider what would - or wouldn't - have been on the menu in those times. Obviously modern convenience foods and snacks are out, so no crisps or fizzy drinks. Sorry, chocolate isn't an option so how about some fruit? It will have to be home-grown fruit such as apples and pears and not exotics like bananas or oranges. And how are you going to carry your lunch and eat it? No plastic sandwich boxes or bottles, no aluminium foil, drinks in cans or plastic bags. You can wrap your food in a cloth such as a tea-towel. Your Tudor meal might include wholemeal bread English cheese e.g. Cheddar Meat, such as ham or a chicken leg Hard boiled egg Fruit (apples, pears) A selection of desserts from the recipes provided Apple juice or weak shandy The museum will provide tables and benches and pottery mugs. The clothes people wore in the 16th century indicated their wealth and social position. The aristocracy wore the finest clothes made from the best fabrics. The amount of jewels sewn to the garments represented the wealth of the owner. The middle classes copied the styles worn by the aristocracy but the clothes were plainer and the fabrics were not as fine. For the working classes clothes were very plain and loose. The men wore sloppy trunk hose with a natural rough shirt. The women wore no corset, farthingale or ruff and the dresses were shorter, making them easier to work in. Queen Elizabeth I probably inherited her love of fine clothes from her father. By the end of her reign she possessed 3,000 dresses which were housed in Richmond Palace, also known as the 'Queen's Wardrobe.' Throughout the Tudor years there was a strong Spanish influence on clothes. This was strengthened by the marriage between Mary I and Philip of Spain. However, towards the end of the century there was a strong French influence which led to a change of style. Children were dressed as exact replicas of their parents. Babies were swathed until six months old. This was supposed to make the baby's arms and legs grow straight. A shirt was worn under the swaddling bands and from time to time during the day the swaddling was removed to give some freedom to the limbs. Little girls were corseted from about the age of five. This led to problems in later life such as deformed shoulders and ribs. In 1565 there was widespread unemployment in the textile industry in England. Home-made woollen clothes were not being worn as much as the foreign garments. The Queen issued a proclamation forbidding the import of materials from the continent. However, this was not very effective because Elizabeth I herself continued to wear expensive foreign materials. HAT A Bowler hat style made from beaver, felt and velvet and decorated with a feather RUFF This was starched to maintain the correct shape Towards the end of the century ruffs were as large as 40cm across. SLEEVES These were very padded which helped emphasise the narrow waist. STOCKINGS and SHOES Queen Elizabeth I wore silk stockings but they were very expensive and most people wore ones made from linen or wool. The shoes were flat and ornately decorated. They were made from leather and satin. HAIR Hair was often curled and worn off the face. Wigs were worn and hair dyes, especially red, were used. ACCESSORIES Often a small mirror was hung from the waist, as was an open fan. Lots of jewellery was worn, especially a long row of pearls and lots of rings. GOWN A Spanish farthingale was worn underneath the skirt. This was a wired or boned, funnel-shaped petticoat. Under the open skirt an ornate kirtle was worn. The materials used were velvets and silks in rich reds, plums and greys. The gowns were decorated with jewels and embroidery. GENTLEMAN RUFF Starched to maintain the shape. As the ruff grew in size a wire framework was inserted under the collar to support it TRUNKHOSE or SLOPS Short padded breeches filled with hair or wool and sometimes boned to give the correct shape. They became so wide that the seats in Parliament had to be widened. STOCKINGS and SHOES The stockings were made from linen, wool or, on occasion, silk and were brightly coloured. Leather boots were worn outside and flat shoes made of leather were worn indoors. HAIR Hair was worn very short and pointed beards were very fashionable. ACCESSORIES Earring in one ear. Dagger, embroidered gloves and handkerchief DOUBLET A fitted body garment which was padded and sometimes boned. It was either buttoned up or laced. HAT Worn on the side of the head and made from beaver, velvet or felt and decorated with a feather. To maintain the shape the hat was filled with paper. Music making and dancing were pastimes enjoyed by people from all sections of society. However, rarely did the classes celebrate together. This only happened on special occasions such as a village festival or the squire's wedding. The most common groups of instruments played by professional musicians were the strings, woodwind and keyboards. Many towns had their own paid bands but for the masses music was usually provided by travelling fiddlers. These were very well paid, earning about £1.00 for two hours work which was equivalent to about a month's wages for an ordinary worker. During the 16th century English music was greatly influenced by Italian and French styles. These were introduced into the Tudor court by foreign ambassadors. In the grand houses music was played at meal times with more elaborate performances on special occasions. Henry VIII eagerly encouraged music making and increased the size of the royal band. By the end of his reign he had a great collection of musical instruments including 76 recorders and 72 flutes. Like her father, Elizabeth I enjoyed music and was a fine performer on the harpsichord. Few people were able to read music and so many songs were passed down by ear. Songs such as 'Greensleeves' were popular as well as ones about Henry III such as 'The Hunt is Up'. Snatches of songs were used by street vendors to advertise their wares; for example 'Lavender's Blue' was originally a street cry. Many musicians honoured their patrons by performing dances in which the aristocracy could take part. Often dances were named in honour of influential members of the court. Dancing was considered to one of the three sports in which a gentleman should excel, the others being jousting and archery. FARANDOLE A chain dance led by the most important person in the hall. This dance can be walked or skipped, etc., ensuring that each person behind the leader follows their exact floor pattern. These patterns took the dancers through circles, spirals, diagonals, zigzags, straight lines and arches of weaving. BRANLE This was a chain or circle dance where the dancers moved further round to the left than the right. Some of these branles were mimed such as the Washerwoman's Branle or the Horse's Branle. They remained popular throughout the Tudor age. PAVAN Unlike the branle, which was of French origin, the Pavan came from Italy. It was a slow stately dance involving couples (one behind the other) and could be danced as a procession or as a figured dance where the performers marked out symmetrical patterns upon the floor. ALMAIN This danced originated in Germany and had a very recognisable foot position where the working leg is raised in the air at the completion of a double step. The dance can be performed with a hop or a lilt and consisted of various figures. COUNTRY DANCES These dances were adopted by courtiers and danced in a more refined manner than they were by country folk. The earlier dances were based on circles, developing into the square sets of couples during the Stuart era and longways sets in the Georgian period. OTHERS The Galliard was an extremely energetic couple dance where each man in turn attempted to out do the previous one by performing complex jumps and turns involving beating the legs against each other. It originated from Italy and was one of Elizabeth's forms of exercise. There are many types of dance which spread from Italy into the courts of Europe which were highly complex both in the use of footwork and in their changes of rhythm. All the dances were taught by dancing masters and were performed both in private chambers and at a court ball held in the Great Hall, banqueting hall or long gallery. Good King Wenceslas looked out, on the feast of Stephen. When the snow lay round about, deep and crisp and even. Brightly shone the moon that night, though the frost was cruel, When a poor man came in sight, gathering winter fuel. 'Sire the night is darker now And the winds blow stronger. Fails my heart I know not now, I can go no longer'. 'Mark my steps, be good my page, Tread though in them boldly; Though shalt find the winter's rage, Freeze thy blood less coldly'. 'Hither page and stand by me, if though know'st it telling, Yonder peasant, who is he? Where and what's his dwelling? 'Sire, he lives a good league hence, underneath the mountain, Right against the forest fence, by St Agnes' fountain. In his master's steps he trod, Where the snow lay dinted. Heat was in that very sod, Which the saint had printed. Wherefore Christian men be sure, Wealth or rank possessing, Ye who now do bless the poor, Shall find themselves a blessing. 'Bring me flesh and bring me wine, Bring me pine logs hither. Though and I shall see him dine, When we bear them hither'. Page and Monarch on they went, On they went together, Through the rude winds wild lament And the bitter weather. In Tudor times the traditional drink for Christmas was the wassail, which means 'good health'. The wassail was made of ale, apples, eggs and sugar and was served hot. The wassail bowl was passed around during the celebration for the purpose of drinking toasts. It was customary for the Lord of the Manor to pass the wassail around among the local peasants. Old Christmas became a symbol of hospitality towards the poor. Boxing Day dates back to the Middle Ages when boxes were placed in churches at Christmas to collect money for the poor. These were opened on the day after Christmas and distributed among the needy. Throughout the 16th century the custom of boxes for farm labourers, apprentices and servants continued. Hunting , for example of squirrels or foxes, was popular on Boxing Day. Wren hunting was also traditional for it was believed that a wren caught on St Stephen's Day (Boxing Day) would protect whoever owned it from shipwreck. From the time of the English Reformation the Puritans had disapproved of the extravagance of Christmas. The Commonwealth banned Christmas in 1644 with an ordinance proclaiming that Christmas Day should be kept as a fast and a penance rather than a feast. Festivities were prohibited but in many areas of England the celebrations continued. The ordinance prohibiting Christmas was abolished in 1660 with t he restoration of King Charles II but its importance had diminished and celebrations waned until they were revived by the Victorians. While shepherds watched their flocks by night, all seated on the ground The angel of the Lord came down and glory shone around. 1 'Fear not , said he, for mighty dread had siezed their troubled mind. 'Glad tidings of great joy I bring to you and all Mankind'. 'To you, in David's town this day is born of David's line, A saviour who is Christ the Lord, and this shall be the sign'. 'The heavenly babe you there shall find, to human view displayed, All meanly wrapped in swaddling bands and in a manger laid'. Thus spake the seraph; and forthwith appeared a shining throng Of angels, praising God, and thus addressed their joyful song. 'All glory be to God on high, and to the Earth be peace; Goodwill henceforth from Heaven to men begin, and never cease'. 1. Ding, Dong, Merrily on high, In Heav'n the bells are ringing. Ding, Dong, verily the sky, Is riv'n with angels singing Gloria, Hosannah in excelsis 2. E'en so here below, below Let steeple bells be swungen. And i-o, i-o, i-o, By priest and people sungen. Gloria, Hosannah in excelsis 3. Pray you dutifully prime Your Matin chime, ye ringers. May you beautifully rime Your Evetide song, you singers. Gloria, Hosannah in excelsis The Boar’s Head Carol (Farandol) The boar's head in hand bear I, Bedecked with bays and rosemary. And I pray you, my masters, be merry, In honour of this company. Caput apri defero Praise God's creatures here below. The boar's head, as I understand, Is the finest dish in all the land. Our steward hath provided this, In honour of the King of Bliss Caput apri defero Praise God's creatures here below. Tudor and Stuart Pastimes Games and Pastimes The sports and games enjoyed by the people of England depended very much upon their social position. There was a wide gulf between the activities of the nobility and those of ordinary people and rarely did the two classes come together. The sports of the nobility were expensive and therefore excluded the common people. Hunting retained its popularity throughout the age. Queen Elizabeth I rode with her hounds until she was quite old. Likewise, James I had a love of hunting. Most of the very grand houses had their own deer parks where hunting took place. The stag was always the King of the chase. Falconry had previously been very popular but it declined in significance once guns became widely available. Similarly, the sport of archery began to decline. Henry VIII had tried to promote archery with a statute in 1541 which restricted bowling and encouraged archery practice. However, in 1595 it was decided that bows and arrows should no longer be kept as offensive weapons but used merely as a pastime. The game of tennis is French in origin but it quickly gained the support of the English nobility. Special walled courts were built and the game could be played either with an opponent or on one's own against the wall. The balls were made of leather and filled with hair. Players hit the ball either with their hands or with a racket. As special equipment and a playing area were needed it was not a sport enjoyed by the ordinary people. Playing bowls and skittles was becoming very popular. It was originally played on the village green but due to the unreliability of the weather wealthy people built indoor skittle alleys; there is one in Wollaton Hall. During his reign Henry VIII added bowling alleys to Whitehall and both Charles I and Charles II are said to have enjoyed the sport. There were many variations of the game including 'Nine pins' where the players stood away from the pins and bowled. The winner was the person who knocked down all the pins in the fewest goes. In the game of 'Skittles' the player bowled from a set distance and then 'tipped' from a position closer to the pins. The players scored one point for each pin knocked over and the winner was the first to reach thirty one points. 'Dutch pins' was a similar game but the pins were taller and more slender with the middle, or 'long pin', taller than the rest. The sports which attracted people of all classes were cock fighting and bear baiting. They were cruel and bloody sports which attracted large audiences and encouraged gambling. In 1526 an amphitheatre for bull and bear baiting was built for Henry VIII. Likewise, from the age of six Elizabeth I had bears and she used them to entertain guests. On the 25th May 1559 Elizabeth gave a splendid dinner and entertained the French ambassador with the baiting of bears and bulls. Before the event the bears were paraded through the streets in order to arouse interest. It was a cruel sport with no pity shown to the animals. However, it was popular with all classes of people at the time. For most people sports and games were restricted to Sundays and church festivals. The pastimes of the country folk were different from those enjoyed by the nobility. They didn't need special equipment and they tended to involve many participants. Traditionally certain sports were played on particular feast days. Football was always played on Shrove Tuesday. This was a Spring festival after the long winter. Football then was a violent game with few rules. A training master was appointed to oversee the game. Whole villages challenged each other. Most people played on foot but some were on horseback. The object of the game was to get the ball to one's village. The football field, therefore, could cover several miles! Other activities on Shrove Tuesday included Tug-of-war and Cock throwing, Easter games were much more gentle such as athletics; running, jumping and throwing. Wrestling was popular amongst the common people and the inhabitants of Devon and Cornwall were celebrated as being the best wrestlers in the Kingdom. For May Day strong ales were brewed and feast were held in the church house. There was dancing around the May pole and throwing the hammer. Running races for women were held and the usual prize was a smock. Throughout the age Puritans criticised the masses for enjoying sports and pastimes on Sundays. They believed that the day should be kept as a day of rest and prayer. James I was against this and issued an edict in 1618 entitled The Book of Sports'. He believed that the prohibition of sports on Sundays would breed discontent and would deprive the common folk of their only opportunity for exercise. The edict did however ban bear and bull baiting on Sundays. The games played by children were similar to those enjoyed by adults, archery was considered to be an essential part of a young man's education even when it was becoming less popular with adults. Sometimes pellets of clay were used instead of arrows. Other games included Leapfrog, Hide and Seek and Hunt the Slipper. Theatre and drama were becoming enormously popular. Actors were often beautifully clothed. Frequently noblemen left their clothes to their servants who made money by selling them to actors. The plays were acted in broad daylight without scenery, lights or an orchestra. There were lots of performances and actors didn't have very long to prepare so they often improvised their lines. The dramas were comedies, tragedies or involved stories of heroes against villains. As well as performances in the houses of the nobility, many plays were staged in the courtyards of a large inns. Huge audiences could be assembled but there were problems of overcrowding. Building of theatres began in London, such as the Swan Theatre in 1593. It was at this time that William Shakespeare came to London and became a part owner of the Globe Theatre in Southwark. By 1595 the London theatres were attracting weekly audiences of 15,000 people. During the Tudor years Nottingham was a small town; in the year 1600 it had a population of about 3,500 people. Since then, of course, the population has increased enormously and the census in 1991 revealed that 263,000 people were living in Nottingham. The centre of Nottingham at this time was the Market Place where the daily trading took place. This was surrounded by rows of narrow streets where the people of the town lived and worked. Many of these streets are still there such as Angel Row, Chapel Bar and Castlegate. Between 1536 and 1542 Henry VIII's chaplain, John Leland, visited Nottingham and was so impressed with the market that he wrote: Nottingham is both a large town and well buildedfor timber and plaster and standeth stately on a climbing hill. The marketplace and street both for building on the side of it, for the very wideness of the street, and the clean paving of it is the most fairest without exception in all England.' Daily life was controlled by a small number of prominent local families. These dominated the Merchant Guild which was responsible for the upkeep of the town, including street paving and fire fighting. The group also controlled trading in the town as well as being the magistrates and tax assessors. The Seven Aldermen took turns to hold the office of Mayor and when one of them died the vacancy was filled by someone suitable. The yearly election of the Mayor was a time for feasting and it usually coincided with Goose Fair. Many tradesmen worked in the town such as weavers, tailors, fletchers (making bows and arrows), potters and shoemakers. Their goods were sold locally and were not usually exported to other towns. A local industry of increasing significance was the coal mining in and around Wollaton. The members of the Merchant Guild were prominent traders and so they often ruled against competition. They forbade 'foreigners' to trade except on Saturdays. An example of their power is an incident that occurred in 1578 when the ironmongery business of Thomas Nix was closed down because he had not served his apprenticeship in the town. Nottingham was divided into seven areas or 'wards'. In each ward the male residents elected a 'petty constable' who was responsible for law and order. The daily enforcement of the law was carried out by the 'watch', a group of men who guarded the streets at night and during times of celebration, such as Goose Fair. The watch had the power to take offenders into custody where they were brought before the magistrates in the borough court. The following are some of the crimes committed in Nottingham: alas, the punishments have not been recorded. In 1523 Robert Taylor, a shoemaker, broke in on a service at St Mary's church and 'spoke Malicious and Contemptuous words' against the vicar. In 1588 the residents of Barkergate petitioned against the wife of a drunken wastrel who milked other people's cows in the middle of the night. The punishment for petty crimes was often turned into a public event, intended to deter those thinking of committing crimes. Such punishments included the stocks, the pillory and the ducking stool. For serious crimes the gaol was below the Guildhall which was used until 1615. In some instances the punishment was made to fit the crime. For example a brewer of ale found to be below standard was made to drink a mug of his own ale and had the rest poured over his head. A baker who offended against the assize by making his loaves too small was paraded through the streets with his loaf tied around his neck. Public health was watched over by the ward aldermen whose duty it was to watch Searchers. out for signs of the plague. Pestilence was a lesser disease which occurred every few years. At Christmas 1586 there was an outbreak in Derby. To prevent further infection people were forbidden to travel to and from Derby and Nottingham. By Tudor times the wool industry was rapidly increasing. Landowners were discovering that wealth could be created by sheep farming. Sheep needed little attention and therefore fewer people were needed to tend them. The population was increasing therefore more clothing was needed. Laws stipulating that those people on low incomes must not wear fine clothes but clothes made of coarsely woven wool and that all men must wear a hat made of wool on Sundays resulted in a greater demand for wool. As the demand for wool grew so more land was turned to grazing including land previously known as common land. This made life very difficult for peasants as many of them could not grow enough food for themselves. Many people moved from the land to towns such as Nottingham and so its population began to rise. There was no help in the towns for those with little or no money. Many people took to the streets, becoming tramps begging for food. The Tudors called them Vagabonds' and they were found in most towns. Monasteries had helped those people, along with the sick and the old, but since the closure of the monasteries by Henry VIII no help had been available. These people became a big problem for the Tudor government who eventually introduced the 'poor laws' to reduce the number of beggars on the streets. Vagabonds were often branded on the tongue if they were caught. If beggars were caught begging without a licence to do so they were whipped until they bled. If they still continued to beg they had part of an ear cut off. Hanging was used if all else failed. Poor laws were not to stop people from being poor but to stop them from starving to death. the beginning of the seventeenth century overcrowding was a serious problem in some parts of Nottingham. Each newcomer was a potential burden upon the town and so in 1612 it was forbidden to build any new cottages or to harbour airy poor person without a licence from the borough authorities. In 1613 a list was drawn up of those people who were to be expelled from the town unless they could prove that they would not become dependent on the Poor Rate. Some measures were taken to help the plight of the poor such as the Spinning School set up in 1627 to help pauper children. Likewise, the Sir Thomas White fund helped young men to start up on their own in business. The Willoughbys were descendants of Ralph Bugge who bought an estate at Willoughby-onthe-Wolds in 1240. His grandson was knighted by Sir Richard de Willoughby and the old name was dropped. The next Willoughby, Richard, married the heiress of the land at Wollaton and so the estate passed to the Willoughbys. The Willoughbys were significant for they represented the 'new rich'. Their fortunes were gained from business ventures such as coal mining and not purely from inheritances. They were landed gentry and took no part in the activities at the Royal Court. It is thought that the Willoughbys were typical of the country squires of their times. During the 16th century there was increasing interest in exploration and this led to voyages of discovery. One such explorer was Sir Hugh de Willoughby, the famous navigator. In 1553 he led the Chancellor's Expedition to the White Sea in search of the North East Passage to India and China. However, during the winter the ships were trapped in ice off Russian Lapland. Two years later, in 1555, Sir Hugh and his sixty two men were found frozen to death. He is said to have been found sitting in his chair with his will on the table in front of him. Francis Willoughby, the builder of Wollaton Hall, was a very wealthy and ambitious man. Much of his fortune came from coal mines at Wollaton and Cossal which provided profits of the huge sum of £1,000 each year in the 1570s. With this money Francis planned to build the new hall at Wollaton which has since been described as 'the most important Elizabethan house in Nottingham and one of the most important in England.' The Hall was to be a lasting memorial to the wealth and position of the Willoughby family. However, during the 1580s the profits from the coal mines began to fall. The coal seams near the surface were exhausted and the deeper coal was more expensive to extract. This loss of income meant that Francis had to obtain funds for the completion of Wollaton from elsewhere. He attempted to mortgage some of his land to the Countess of Shrewsbury (later to become known as Bess of Hardwick). She offered to lend him £3,000 out of friendship but kept the land as security until the debt was repaid. Together with mounting debts Francis' personal life was beset with problems. His first marriage ended in divorce and despite remarrying, both unions provided only daughters and no son and heir. Although Francis Willoughby fulfilled his ambition with Wollaton Hall, in doing so he left huge debts for his successors, Bridgett and Percival Willoughby. A stone over the South door at Wollaton Hall reads "Behold this house of Francis Willoughby, an unhappy and heirless but ambitious man". A further Willoughby of significance was Francis Willoughby, the famous naturalist. He was an eminent scholar and one of the original Fellows of the Royal Society. Whilst studying in Cambridge in 1653 he met John Ray, the botanist. Both men had similar ambitions and shared a love of natural history. They specialised in the identification and classification of animals and plants. This field of study was of increasing importance during the 17th century as a result of the voyages of discovery to many parts of the world. The traditional English pastimes, such as falconry and hunting, were declining in popularity and were being replaced with new, more cultural forms of entertainment. There was a greater appreciation of the world of nature and a desire for further knowledge about natural history. Francis accompanied John Ray on a series of expeditions throughout England and the Continent in search of specimens. It was during their travels that the men realised that there was a lack of documentation. They endeavoured to resolve this with Francis concentrating on animals, fish and insects and John Ray focusing on botany. This research was to be the foundation of the work 'Ornithologia' which was a system of classification. The book was divided into three volumes and gave details of all known birds. This was to prove very beneficial to future naturalists. Whilst on a tour of Spain in 1664 Francis had the opportunity to learn more about whales. This was later recorded in his book 'Historia Piscium 1 in which he was the first naturalist to provide accurate descriptions of often rare species. During the final years of his life Francis began the study of many different types of insects, including bees and wasps. This was later included in his work 'Historia Insectorium1. Due to Francis Willoughby's untimely death from pleurisy at the age of thirty seven, it was left to John Ray to complete Francis' three major works which were later published in Latin. As a tribute to his friend John Ray wrote of Francis in the introduction to Ornithologia 'He was endowed with excellent gifts such as piercing wit, sound judgement and great industry . . . he was from his childhood addicted to study . . . and was eminent for virtue and goodness. 1 Sir Hugh Willoughby, Exprorer The Search for the North-East Passage For two thousand years spices, perfumes and silks were brought along the Silk Road from China, through mountains and deserts to Samarkand, on to the great city of Constantinople and so to Europe. But by the middle of the fifteenth century this trade had all but ceased as the Turkish empire took control of the Silk Road and captured Constantinople. So another route had to be found to bring these fabulous riches to Europe. Christopher Columbus discovered the Americas whilst trying to sail westwards to India and China. Indeed, not realising just how large the Earth is, he thought he had reached them. Later the Spanish and Portuguese conquered much of South America and could stop ships from other countries from going south and west around Cape Horn to the Pacific and on to the Far East. Likewise, trade to the south and then eastward around Africa was in the hands of the Portuguese. So the English merchants tried to find a way around the north of Europe and Asia - the North-East Passage. In 1550 English merchants formed the 'Mysterie and Company of Marchant Adventurers for the Discoverie of Regions, Dominions, Islands and Places Unknowen 1 to find the North-East Passage. Three years later its first expedition of three ships was ready; the Bona Esperanza, the Edward Bonadventure and the Bona Confidentia. There were a total of 155 men, including three surgeons and sixteen merchants, with provisions for eighteen months. Their leader was Sir Hugh Willoughby. He was not a sailor but an experienced and distinguished soldier. They set sail from London down the River Thames. As they passed the Royal palace at Greenwich the crews cheered and fired their cannons whilst the courtiers and common people crowded along the riverside to see them pass. But it was six weeks before they finally sailed from the east coast of England, a delay which was to cost them dear later in the voyage. For three weeks they were out of sight of land and Sir Hugh noted in his journal: We sayled with divers other courses, traversing and tracing the seas, by reason of sundry and manifolde contrary windes'. They eventually sighted the coast of Norway and continued northwards, past the Arctic Circle and turned eastwards around North Cape. They were trying to find the town of Vardo (which the English called Wardhouse), the last town before the barren wastes of arctic Russia. But the ships were beset by dreadful weather: 'The land being very high on every side, there came such flames ofwinde and terrible whirlewinds, that we were not able to beare in, but by violence were constrained to take to the sea agayne, ourpinnesse /small sailing boat/ being unshipt; we sailed North and by East, the wind increasing so sore that we were not able to beare any saile, but tooke them in, and lay a drift, to the end to let the storme over passe. And that night by violence ofwinde, and thicknesse of mists, we were not able to keep together within sight, and then about midnight we lost ourpinnesse, which was a discomfort unto us. As soon as it was day, and the fog overpast, we looked about, and at last we descried one of our shippes to Leeward of us, which was the Confidence, but the Edward we could not see'. These two ships sailed together in weather even more dreadful, completely lost, for fortyfive days. They tried to find Wardhouse but they were unsuccessful for they had no charts and their navigation was uncertain: then wee sounded, and had 160fathomes, whereby we thought to befarrefrom land and perceived that the land lay not as the Globe made mention'. Once they sighted land but there was a lot of ice around it and shallow water and they were not able to reach it. This may have been the island of Novaya Zemlya. Later, on more than one occasion, they saw another coast but were in danger of being driven onto the shore and wrecked so they sailed out to sea again and lost sight of it. They were running out of time as the short arctic summer slipped away and the dreadful winter approached. In October they managed to get their two ships into a sheltered bay on the desolate Kola peninsula. Sir Hugh Willoughby's last entry in his journal records their fate: Remaining in this haven the space of a weeke, seeing the yearefarre spent, & also very evill wether, as frost, snow, and haile, as though it had been the deepe of winter, we thought it best to winter there. Wherefore we sent out three men Southsouthwest, to search if they could find people, who went three dayes journey, but could find none; after that, we sent other three Westwardfour daies journey, which also returned without finding any people. Then we sent three men Southeast three dayes journey, who in like sorte returned without finding of people, or any similitude of habitation. During the terrible arctic winter Sir Hugh and the officers and crew of the two ships all froze to death. They had sailed for three hundred miles beyond the town of Wardhouse. The third ship, the Edward Bonadventure, from which they had parted company so many weeks earlier, did find Wardhouse. The captain, Richard Chancelor, was very worried about the other ships, being very pensive, heavie, and sorrowfull... not a little troubled with cogitations and perturbations ofminde. He sailed to the east but failed to find Sir Hugh and his company. Instead he found the Russian town which is now called Archangel and spent the winter there. Chancelor and the merchants then visited Moscow and so were able to start a most profitable trade with Russia. In 1555 Richard Chancelor sailed again to the arctic and found Sir Hugh Willoughby's ships. His crews sailed them back but the Bona Confidentia was destroyed on the coast of Norway and all the crew were lost. The Bona Esperanza was lost at sea and finally Richard Chancelor's ship was driven by storms onto the Scottish coast and he was drowned. Other attempts were made to explore this region but the elusive North-east Passage never was found for a sailing ship could never pass the ice around Novaya Zemlya. Explorers turned their attention to finding a North-west passage around the north of Canada, a quest that was to be equally as unsuccessful and tragic. TUD#2\TUDHUGH.PM4 William Morice KntOne of his Matiesmost Honourable Privy Councill, and Principall Secretary of State You are upon sight hereof to suffer the Bearers Francis Willoughby Esq. & Nathaniel Bacon, Gent, with two servants, their wearing apparell, & other necessaries, freely to pass beyond the seas, for their experience, and improvement by travell; Provided they carry no prohibited goods, and do all such things, and give all such cautions as by the Laws and Statutes of this Realme of England are in that case required and provided for: And you are in like manner to suffer them & either of them to return againe when their occasions shall require, Without any lett, hindrance or molistacon. Hereof of you are not to faile; and for so doing this shall be your warrant. Given at Whitehall the Tenth day of Aprill, 1663 To all Captains of his Maties Ships at Sea, Governors, Comanders, Souldiers, Maiors, Sherifs, Justices of the Peace, Bailiffs, Constables, Customers, Comptrollers, Searchers, or others whom it may Concerne Reproduced from the Middleton Manuscripts by permission of Nottingham University Manuscripts Department Will Morice The Willoughby family moved to Wollaton in 1450 where they lived in the original hall which was in the village near to the church. It was not very grand and Francis Willoughby decided to use the profits from his coal mines to build a new hall which would represent the wealth of the Willoughby family. The site of the new hall was on gently rising ground which had beautiful views of the surrounding countryside. It was a prominent position with a park which at that time covered an area of 784 acres. Deer were kept in the park for hunting. The designer and builder of Wollaton Hall was Robert Smythson who had previously been the Master Mason at Longleat. The Willoughbys were obviously pleased with his work as there is a monument to Smythson in Wollaton church which reads 'Mr Robert Smythson, gent, architect and surveyor unto the most worthy house of Wollaton After completing Wollaton Hall Smythson worked on a number of other buildings in the area, the most notable being Hard wick Hall. Building of the new hall began in 1580 and it was completed in 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada. It was built of Ancaster stone obtained in exchange for coal from the Wollaton mines. Cassandra Willoughby claimed in 1702 that the cost of Wollaton Hall had been 'four score thousand pounds' but it is believed that the actual cost was £8,000 which was still a huge sum in the 16th century. As well as celebrating the wealth and prestige of the Willoughby family, the house was significant as it was built using 'new' money, that is money gained from business rather than by inheritance. An engraving on the south side of the building reads 'Behold this house of Sir Francis Willoughby, built with rare art and bequeathed to Willoughbys. Begun 1580 and finished 1588'. The hall reflected a change of style. It was not built for defence purposes like a castle but more as a country house. It differed from other Elizabethan mansions due to its total symmetry. Smythson ignored the conventional E or H shaped building and created a house built around a central hall with smaller rooms surrounding it. The perfect symmetrical design of Wollaton Hall also extends into the grounds. The house, gardens and outbuildings all form a large square. Smythson was influenced by French and Flemish styles and decorated the exterior of the building with ornate windows, gables and statues of which there are said to be nearly two hundred. To complete the detailed carving Sir Francis employed some of the best stone masons in England, for example Christopher Lovell who had worked at Longleat. The main feature of the interior of Wollaton is the Great Hall. The room is 15m (50ft) high with a hammer beam timber roof above it. The huge windows are l l m (35ft) from the floor and below these were hung paintings. The room was quite plain apart from the ornate screen at the west end of the hall above which the organ was later placed. The other rooms on the first floor included the salon, library and family dining room. Along the east side of the building was a long gallery where it was fashionable to include portraits of members of the family. Above the Great Hall is a large room which was known as the Prospect Room. This formed the third storey of the building. The Prospect Room has always been a bit of a mystery. It has been suggested that it may have been a ballroom but historians now believe that this is unlikely as access to it is very restricted. It was, however, used as a dormitory for guests and their servants - when it was known as 'Bedlam1. This use was at a much later period when the number of servants had increased especially during the Victorian age. Use of the Prospect Room during the Tudor period was most likely to enable ladies and older members of the household to follow the progress of the hunt taking place in the grounds. Smythson built the Hall above ground level in order to hide the kitchens and servants quarters underground. These, however, were well lit due to the windows which were placed at ground level. A list of members of the household in 1598 included forty six names of which at least twenty nine were servants. These include 'Old Bassett, Simon Setter the slaughterman, the Ketchen boye, Edward Hancockes the gardener and Deffe Thorn'. Not all the servants working at Wollaton Hall in the Tudor period lived in the building itself. Some of them came from the village of Wollaton on a daily basis. Some, it is believed, stayed in the Old Hall and walked to the new hall each day to carry out their duties. Below the basement were a series of passageways which were used as wine cellars. There is also a well of ice-cold water known as the Admiral's Bath. With Wollaton Hall Francis Willoughby fulfilled his ambition to build a lasting memorial to his family. He created a magnificent hall which has been described as 'the most important Elizabethan house in Nottingham and one of the most important in England,'