Geology of the Hawaiian Islands

advertisement

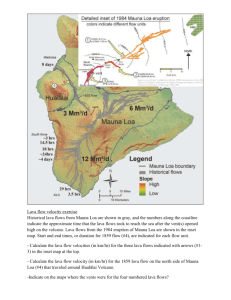

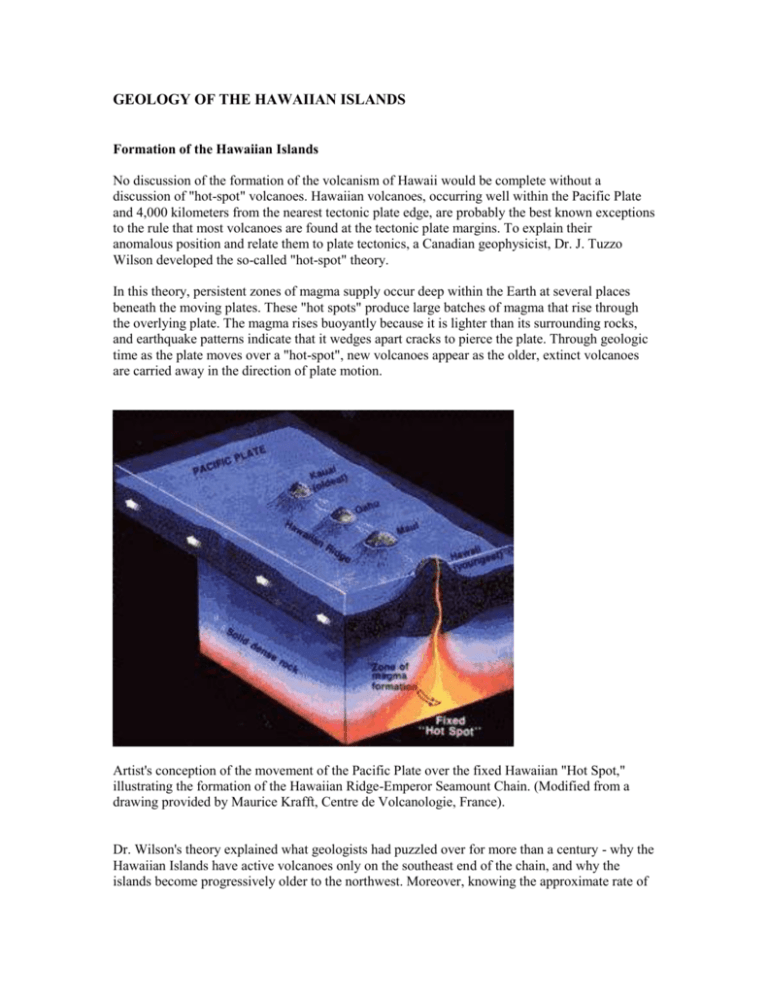

GEOLOGY OF THE HAWAIIAN ISLANDS Formation of the Hawaiian Islands No discussion of the formation of the volcanism of Hawaii would be complete without a discussion of "hot-spot" volcanoes. Hawaiian volcanoes, occurring well within the Pacific Plate and 4,000 kilometers from the nearest tectonic plate edge, are probably the best known exceptions to the rule that most volcanoes are found at the tectonic plate margins. To explain their anomalous position and relate them to plate tectonics, a Canadian geophysicist, Dr. J. Tuzzo Wilson developed the so-called "hot-spot" theory. In this theory, persistent zones of magma supply occur deep within the Earth at several places beneath the moving plates. These "hot spots" produce large batches of magma that rise through the overlying plate. The magma rises buoyantly because it is lighter than its surrounding rocks, and earthquake patterns indicate that it wedges apart cracks to pierce the plate. Through geologic time as the plate moves over a "hot-spot", new volcanoes appear as the older, extinct volcanoes are carried away in the direction of plate motion. Artist's conception of the movement of the Pacific Plate over the fixed Hawaiian "Hot Spot," illustrating the formation of the Hawaiian Ridge-Emperor Seamount Chain. (Modified from a drawing provided by Maurice Krafft, Centre de Volcanologie, France). Dr. Wilson's theory explained what geologists had puzzled over for more than a century - why the Hawaiian Islands have active volcanoes only on the southeast end of the chain, and why the islands become progressively older to the northwest. Moreover, knowing the approximate rate of motion of the Pacific Plate, Dr. Wilson's "hot-spot" concept predicts what the age of the older volcanic islands should be. Dating of the various Hawaiian Islands by measuring minor amounts of radioactive elements and their daughter products in ancient Hawaiian lava flows indicates progressive increase in age to the northwest consistent with the "hot-spot" concept. Kauai is 5 million years older than, and 500 kilometers northwest of, the Big Island of Hawaii. The overall track of the Hawaiian Hot Spot - marked by the submarine Hawaiian Ridge and Emperor Seamounts - cross another 5,500 kilometers of the North Pacific seafloor. The active volcanoes of the Big Island are less than a million years old, but the Hawaiian Hot Spot has persisted for at least 75 million years. It has generated about 200 Hawaiian-type volcanoes, most of them now submerged, during its lifetime and is still going strong. The latest is the Loihi Seamount. Map of part of the Pacific basin showing the volcanic trail of the Hawaiian hotspot-- 6,000-km-long Hawaiian Ridge-Emperor Seamounts chain. (Base map reprinted by permission from World Ocean Floor by Bruce C. Heezen and Marie Tharp, Copyright 1977.) Map of the current location and depth measurements of the Loihi Seamount. There are a few hundred volcanic islands that have been built above the seafloor. Arguably, and as mention previously, the most spectacular example is the island of Hawaii, the Big Island and the youngest island in the Hawaiian-Emperor chain. This chain of about 200 volcanoes is 5,500 kilometers long. The volcanoes range in age from 75 million-year-old volcanoes at the northwestern end, near Siberia, to the present day active volcanoes at Kilauea and Mauna Loa at the southeastern end. Mauna Loa volcano stands 9,300meters above the floor of the Pacific Ocean. Most volcanoes of the Hawaiian-Emperor chain are remnants that were built 5,00 to 10,000 meters above the Pacific Ocean as shoals and seamounts but are now eroded to below water level. Most of the younger end of the chain - the Hawaiian Islands - is severely eroded and flanked in places by spectacular seacliffs. And the Hawaiian-Emperor chain is continuing to lengthen. The new volcano, the Loihi Seamount, is being built on the seafloor 1,000 meters below the sea surface, 44 kilometers southeast of the island of Hawaii. Current Eruptions Only volcano Kilauea is currently in an eruptive state. Hawaiian eruptions, which are generally of basaltic magma, destroy property, but the lava flows produced by them rarely catch people off guard. Plenty of warning is given, and most lava flows are slow enough to be outrun and avoided. Not all of the five million tourists who visit Hawaii each year want to visit vast barren lava fields or small sulfur gases, but many of them make an effort to see a volcano in eruption. On the day west coast (Kona Coast) of the island Hawaii, which is locally known as the Big Island, and in the island's main city of Hilo, visitors can catch helicopter or plane flights to view the eruptions. Kilauea Volcano's Pu'u O'o in eruption. Kilauea Volcano on the Island of Hawaii, known also as the Big Island, is the most thoroughly studied volcano in the world. It is also one of the most active, with many eruptions and glowing lava lakes that stir and boil for years at a time. Almost all its eruptions are relatively quiet outpourings of fluid lavas. The word quiet can be misleading, though, for the vents often spurt fire fountains of incandescent lava several hundred meters high, which fall into lava pounds or feed lava flows. Those outpourings of lava are quiet only in contrast to explosive volcanic eruptions, which produce fragmental debris and look more like huge detonations of dynamite. Effusive eruptions of the Hawaiian type are comparatively safe to study at close range, and the Hawaiian Volcano Observatory has been at it since 1912. Kilauea Volcano now erupts more often than Mauna Loa and has destroyed many works of man, as it did the village of Kapoho and the surrounding farmland in 1959-1960. In December 1965, the ground around Kapoho was still warm. And from February 1972 to July 1974, Mauna Ulu ("growing mountain"), on Kilauea's east rift, erupted continuously for 901 days producing 162 million cubic meters of lava that covered 46 square kilometers. Lava reached the seashore through a 12-kilometer-long system of lava tubes and entered the sea, producing great quantities of steam with munch hissing, sometimes explosively as a wave broke over a lava tube and trapped the steam inside. Sometimes, the red-hot lava slipped into the sea with surprisingly little fanfare, but when confined in small spaces, the water and lava produced small explosions. Without such confinement, the overwhelming volume of ocean water simply couldn't be heated fast enough by the comparatively small volume of lava to cause an explosion. Lava flows from this particular eruption seared large sections of the Chain of Craters Road the linked the national park to the southeast coast, but there was little loss of private property, for the lava from this eruption stayed within national park boundaries. The Mauna Ulu eruption was particularly educational for the curious public, and therefore beneficial to the tourist industry, because access was possible to Mauna Ulu via the Chain of Craters Road. Lava lakes and minor lava fountaining were visible from safe observation points established by the National Park Service and the Volcano Observatory. Current Issues Ever since lava first erupted above sea level over 500,000 years ago to begin building the Island of Hawaii, countless eruptions from its five volcanoes have built the Big Island to a towering height of more than 4,000 m (13,000 ft). Its two most active volcanoes -- Mauna Loa and Kilauea -- erupt lava frequently enough to pose a serious hazard to property on many parts of the island. About 40 percent of Mauna Loa has been covered by lava in the past 1,000 years and over 90 percent of Kilauea's surface is covered by lava less than 1,100 years old. As land development expands toward areas of relatively high hazard, the threat to life and property on Hawaii will increase accordingly. New land the size of several football fields can collapse into the ocean with little or no warning, and the intensity of lava-seawater explosions can change suddenly. Hazard zones from lava flows are based chiefly on the location and frequency of historic and prehistoric eruptions and the topography of the volcanoes. Scientists have prepared a map that divides the five volcanoes of the Island of Hawaii into zones that are ranked from 1 through 9 based on the relative likelihood of coverage by lava flows. Potential Eruptions Mauna Loa has grown rapidly during its relatively short (600,000 to 1,000,000 years) history to become the largest volcano on Earth. Although its rate of growth appears to have slowed in the past 100,000 years, our detailed geologic research on the volcano has nevertheless shown that about 98 percent of the volcano's surface is covered with lava flows less than 10,000 years old! Based on reliable ages of nearly 200 of these flows, it has been found that Mauna Loa has erupted in time and place in fundamentally different ways -- as eruptions from the summit of Mauna Loa become larger and more frequent, eruptions from the rift zones decline. A cyclic model was recently proposed for the volcano's summit-flank alternation of eruptive activity. Detailed geologic mapping suggests that the cycles may last about 2,000 years each. Since the most recent period of intense summit activity began about 2,000 years ago, perhaps Mauna Loa is "on the verge of shifting to a period of long-lived lava-lake activity, shieldbuilding, increased summit overflow, and diminished rift zone eruptions." Vents at 2,900-m level supply lava for remainder of the 1984 eruption of Mauna Loa. Photo taken on March 26, 1984. Currently, at Mauna Loa, inflation is continuing at the summit, where the GPS network first showed definite lengthening of the lines across the summit caldera in late April or May 2002, after nearly 10 years of slight deflation. The summit expansion tailed off and perhaps stopped in mid-winter 2002-2003. It then resumed, starting on about February 15, 2004, slackened, and once more began in late April or early May. The lengthening again slowed during the summer but accelerated as summer ended. We interpret the lengthening, uplift, and tilting to indicate resumed swelling of the magma reservoir within the volcano. Seismicity, however, remains low. Mauna Loa last erupted in 1984. Another volcano on Hawaii worth considering for a future eruptive event is Mauna Kea Hawaii's tallest volcano at 4,205 meters. Mauna Kea is presently a dormant volcano, having last erupted about 4,500 years ago. However, Mauna Kea is somewhat likely to erupt again. Its quiescent periods between eruptions are long compared to those of the active volcanoes Hualalai (which erupts every few hundred years), Mauna Loa (which erupts every few years to few tens of years) and Kilauea (which currently erupts almost every year). A swarm of earthquakes beneath Mauna Kea might signal that an eruption could occur within a short time, but such swarms do not always result in an eruption. Sensitive astronomical telescopes on top of Mauna Kea would, as a by-product of their stargazing, detect minute ground tilts possibly foretelling a future eruption. The Newest HawaiianVolcano Hawaii's newest volcano, the Loihi Seamount, is currently being built on the seafloor 969 meters below the sea surface, 44 kilometers southeast of the island of Hawaii. The Loihi Seamount has an edifice 2,700 meters above the floor of the Pacific. If growth continues at the present rate, it will emerge at sea level in about sixty thousand years. Manned submersibles have been used to observe the Loihi Seamount since about 1987, providing an unparalleled opportunity to observe a seamount grow. Loihi Seamount is an active volcano built on the seafloor south of Kilauea about 44 km from shore. The seamount rises to 969 m below sea level and generates frequent earthquake swarms; the most intense of which occurred in 1996. An eruption at Loihi has yet to be observed, but scientists from the University of Hawaii have recently made many submersible dives to the volcano and deployed instruments on its summit to study Loihi in much greater detail. A bulbous pillow lava from Loihi's summit area. Most of the rocks to be found on Loihi's summit are coated by some amount of fine sediment and/or clay minerals that come from the interaction of sea water with the rock's surface. Only the very youngest rocks typically are sediment-free in this environment. The summit of Loihi is marked by a caldera-like depression 2.8 km wide and 3.7 km long. Three collapse pits or craters occupy the southern part of the caldera; the most recent pit formed during an intense earthquake swarm in July-August 1996. Named Pele's Pit, the new crater is about 600 m in diameter and its bottom is 300 m below the previous surface! Like the volcanoes on the Island of Hawaii, Loihi has grown from eruptions along its 31-km-long rift zone that extends northwest and southeast of the caldera. Written By R. B. Trombley, Ph.D. Southwest Volcano Research Centre Apache Junction, Arizona USA