The Energy Situation in Britain

advertisement

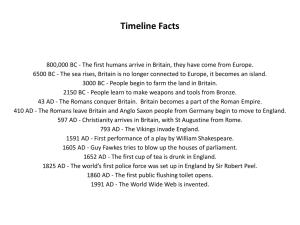

The Energy Situation in Britain Energy prices have risen to extremely high levels in recent years, as more and more countries worry about securing their future energy supply. Britain is lucky, with its large oil and gas reserves in the North Sea. However, production from the North Sea is declining and Britain will have to make some difficult decisions about energy sources in the future. Electricity demand has risen significantly and is about 60 per cent higher than 30 years ago. ‘Hundreds of thousands of homes across the UK came within hours of power cuts after the National Grid issued an emergency call for electricity companies to reduce demand on one of the coldest days of the year. The companies were preparing to cut power or dim the lights on Thursday by lowering the voltage, after the grid issued a warning of a possible problem between 4.30pm and 6.30pm. Power generators were told to make more power available to the system, while distribution companies were informed that if no more power were made available they might have to cut some customers off temporarily. The highly unusual shortage comes as fears mount over the security of Britain’s energy supplies.’ The Times, 31st December 2005 Introduction After having been a net exporter of energy for the past two decades, Britain is about to become a large net importer. The country is rapidly running out of the significant reserves of oil and gas that made it a leading producer over the last three decades. In 2005 Britain became a net importer of natural gas and is expected to lose its self-sufficiency in oil by 2009. To add to this, the British coal industry has continued its considerable decline in recent decades. By 2020 Britain will be importing about three quarters of its primary energy needs. There are growing fears that energy could become a political weapon. Many of the country’s coal and nuclear power stations have been in service for a long time and will need to be closed in the next decade or so, requiring substantial new investment to maintain the country’s generating capacity. Many parts of the energy distribution network are also ageing and in need of considerable investment. New development will be costly and will involve some difficult governmental decisions. The primary role of government in terms of energy is to ensure continuity of supply. The government is also under considerable pressure, internationally and nationally, to reduce the amount of pollution caused by energy production and consumption. It has also set the country the optimistic target of reducing greenhouse emissions by 60 per cent by 2050. These interconnected priorities will clearly have a considerable impact on the energy choices Britain makes now and in the future. Sources of British energy Figures 1 and 2 show how Britain’s share of energy consumption by source has changed since 1990. The main changes are: a modest decline in the share of petroleum a very considerable rise in the relative importance of gas an equally significant decline in the share of coal. The contribution of nuclear power and other sources of energy (mainly hydroelectric power) changed little during this period. Figure 1. Britain's energy consumption by source, 1990 and 2004. Figure 2. Sources of energy—percentage of total. Oil and gas The North Sea is classed as one of the world’s great energy provinces. However, it is thought that Britain has already taken between half and three quarters of the oil and gas within its territorial waters. Much of the remaining North Sea reserves are in small and remote fields that are more expensive and more difficult to access than those fields already in production. British oil production peaked at the end of the 1990s, and it has now fallen by about 30 per cent to around 2 million barrels a day. By 2010 it could be down to 1.2 million barrels a day. During the same period it has been estimated that natural gas production will fall from 9,400 million cubic feet to about 6,000 million cubic feet. Figure 3 shows Britain’s oil balance from 1997, while Figure 4 illustrates the decline in the average size of British oil and gas fields commencing production since the mid-1960s. The trend in Figure 4 is very significant indeed. Figure 3. How Britain became a net oil importer. Figure 4. Average size of British oil and gas fields commencing production. Figure 5 illustrates the sources of Britain’s gas supply, with more than 90 per cent coming from the North Sea. Approximately 10 per cent is imported via the European gas network. Only 2 per cent of Britain’s gas supply comes from Russia, a figure well below that of many mainland European countries. The importation of liquefied natural gas (LNG) to a plant on the Isle of Grain began in 2005. Figure 5. Where Britain's gas comes from. Clearly, gas imports will rise in the future. There is no other choice, as gas is projected to account for an increasing share of electricity generation (Figure 6). This is primarily because gas is the least polluting and most flexible of the fossil fuels. Figure 6. British electricity generation by source. The government is trying to encourage development of the remaining reserves in the North Sea by various means. 1. One way is a policy under which oil fields left fallow by their owners may be given to other companies with plans to develop them. 2. Also, as many of the largest fields decline in production and become less profitable to the large oil companies, smaller companies are taking their place. Smaller companies are generally satisfied with smaller profits than the ‘majors’ and have been greatly encouraged in their efforts by the very high price of oil over the last few years. New techniques are being developed to extract more oil than previously possible from North Sea oil fields on both the British and Norwegian sectors. An example applies to the Miller oil field 240 kilometres northeast of Peterhead in Scotland. Production from the Miller oil field peaked in 1995 and was due to shut down by 2007. However, by injecting carbon dioxide from a mainland power station into the oil field (Figure 7) it has been estimated that an additional 40 million barrels of oil could be extracted. This would increase the life of the Miller field by 15 to 20 years. Figure 7. A new way to extract oil from an oilfield. Nuclear power Figure 8 shows the current distribution of Britain’s nuclear power plants. No other source of energy creates such heated discussion as nuclear power. The biggest issue, although not the only one, is the huge cost and possible environmental consequences of radioactive waste disposal. Until the middle of 2005 it seemed unlikely that Britain would consider building a new generation of nuclear power plants. In fact, the 2003 Energy White Paper described nuclear power as ‘an unattractive option’. However, with falling energy production in the North Sea and concerns about possible supply disruptions on imported energy, nuclear energy appears to be back on the agenda. The government is faced with the difficult decision of either allowing the industry to run down gradually as old plants have to be closed or to build new plants. A significant problem is that it takes at least ten years to plan and build a nuclear reactor. Figure 8. The planned lifetime of Britain's operating nuclear power stations. Environmental organisations such as Greenpeace are absolutely opposed to nuclear power. Their main objections are: the risk of a major accident spreading radioactivity into the atmosphere and hydrosphere the production of radioactive waste which will remain in a potentially dangerous state for centuries. The proponents of nuclear power argue that it is the only way that Britain can avoid electricity shortages and meet its climate change obligations at a reasonable cost. A recent report by the investment bank UBS calculated that nuclear electricity is cheaper than gas as long as oil is above $28 a barrel (natural gas prices are closely linked to the price of oil). Without the construction of new power plants, the share of nuclear-generated electricity will decline from 23 per cent in 2005 to 7 per cent by 2020. Nine of the country’s twelve nuclear plants are due to be closed in the next ten years. Coal At the beginning of the twentieth century coalmining was the country’s biggest employer. At its peak the industry employed a million workers. However, at the end of March 2005 there were only 42 opencast sites and eight major deep mines in production in Britain (Figure 9). Employment totalled 9,300 of which 6,600 were employed in deep mines. In 2004, total British coal production was 25.1 million tonnes with 12.5 million tonnes from deep-mined production and the remainder from opencast workings. The mining company UK Coal produces half of the national output. Figure 9. Distribution of coal mines and opencast operations. Coal is the dirtiest and the most inflexible of the fossil fuels, two significant reasons for its declining importance in the British energy market. Coal produces twice as much carbon dioxide as gas. The fact that virtually all of the country’s easily accessible coal has already been mined is the other major factor for declining production within the country. Total British coal consumption in 2004 was 60.6 million tonnes with 33 per cent of electricity generated in 2004 coming from coal. The country has nineteen coal-fired power stations, the largest of which is Drax. Very little British coal is exported. However, imports are very significant, amounting to 36.2 million tonnes in 2004. Major sources of imports include the USA, Australia, Columbia, Poland and South Africa. However, the coal industry in Britain may be on the point of a limited comeback with the development of ‘clean coal technologies’. In February 2006, Trade and Industry Secretary Alan Johnson talked of a ‘renaissance’ for coal. This new technology has developed forms of coal that burn with greater efficiency and capture coal’s pollutants before they are emitted into the atmosphere. The latest ‘supercritical’ coalfired power stations, operating at higher pressures and temperatures than their predecessors, can operate at efficiency levels 20 per cent above those of coal-fired power stations constructed in the 1960s. Existing power stations can be upgraded to use clean coal technology. Hydroelectric power Britain generates only about 0.8 per cent of its electricity from HEP. Most of the large-scale plants (producing more than 20 megawatts) are located in the Scottish Highlands. The most recently constructed plants have energy conversion efficiencies of 90 per cent and more. There are very few opportunities to increase large-scale HEP production in Britain as most commercially attractive and environmentally acceptable sites are already in use. However, in July 2005 Scottish Ministers approved plans to build a new HEP generating station at Glendoe, near Fort Augustus in Inverness-shire. The power station will be built underground at the side of Loch Ness. The new plant will generate up to 100 megawatts of electricity, sufficient to meet the power requirements of 37,000 homes. Glendoe will be the Scotland’s first large-scale conventional HEP plant to be built since 1957. It has been estimated that if small-scale HEP from all of the streams and rivers in Britain could be tapped it would be possible to meet just over 3 per cent of the country’s total electricity needs. Other renewable forms of energy According to the Department of Trade and Industry, ‘renewable energy is an integral part of the government’s longer-term aim of reducing CO2 emissions by 60 per cent by 2050’. The government has set a target of 10 per cent of electricity from renewable sources by 2010. In 2003, biomass used for both heat and electricity generation accounted for 87 per cent of renewable energy in Britain. The majority came from landfill gas (33 per cent) and waste combustion (14 per cent). Electricity production from biomass accounted for 1.55 per cent of total electricity supply in 2003. Of the other available sources of renewable energy, wind seems to be the only new renewable source of energy available to Britain in any significant quantity. Nevertheless, there has been some progress with other forms of renewable energy. For example: A small geothermal power plant is in operation in Southampton. Opened in 1986, it provides heating and cooling systems for a number of domestic and commercial consumers. The plant uses hot water from deep below the city. In 2003 the total capacity for solar photovoltaic energy in Britain was only 6 megawatts. There are two wave power devices operating in Britain, both in Scotland. The total capacity amounts to 1.25 megawatts. Wind energy Scroby Sands, Britain’s newest and largest wind farm, was officially opened in March 2005. It is located on a sand bank 3 kilometres off the coast of Great Yarmouth. Its 30 turbines can produce sufficient electricity for 41,000 homes. The wind farm is owned by the German power company Eon. Compared to coal-fired electricity generation, Scroby Sands should cut 75,000 tonnes of carbon dioxide emissions each year. The government promotes wind power at least partly to help meet its commitment to reduce carbon monoxide emissions. Figure 10 shows the situation of Britain’s wind energy projects in the middle of 2005. Figure 10. Wind energy projects. Under the ‘renewables obligation certificates’, energy companies are obliged to generate part of their electricity through renewable sources. At present the requirement is 4.3 per cent but this will rise to 15 per cent by 2015. Power companies without renewable sources of energy can meet their obligation by buying credits from other companies that operate renewable energy facilities. The credit system has resulted in significant payments from conventional power companies to ‘green’ operators. Conventional power companies are also subject to a climate change tax. In 2005 the National Audit Office estimated that total financial assistance to the renewable energy industry (mainly wind farms) amounted to £700 million a year. This is expected to rise to £1 billion by 2010. A recent estimate by the trade magazine Platts Power UK was that renewable energy capacity would rise 21-fold between 2005 and 2010. If this materialises, 7 per cent of Britain’s electricity supply will come from wind. It takes about three years from planning consent for a wind farm to become operational. A recent report by the Royal Academy of Engineering stated that the only forms of electricity more costly than wind power are wave power and poultry-litter power (Figure 11). The worlds’ first poultry-litter power plant was built at Eye in East Anglia in 1992. According to the report, wind power is 70 per cent more expensive than gas or nuclear power. Because of variations in weather conditions, Britain’s wind farms operate at only 31 per cent of capacity. On the basis of the average spacing of wind turbines and the power that they produce, it can be estimated that a wind farm the size of Dartmoor would be needed to produce the same output as an average conventional power station. Figure 11. Cost of generating electricity. Microgeneration There has been a developing interest in new small-scale energy generators. In Britain, microgenerators are generators with an output of less than 50 kilowatts. Photovoltaic tiles and small wind turbines on roofs are no longer a rarity. If these were installed in large enough numbers they could take a considerable strain off overloaded distribution grids. A recent article in the New Scientist quoted a spokesperson for the Micropower Council, the British industry association that promotes small-scale power generation, as saying: ‘We are talking about turning power generation into consumer products that you can buy at a DIY store.’ The government-sponsored Energy Saving Trust (EST) estimates that home-powered generators of various types could provide 30 to 40 per cent of the Britain’s electricity needs by 2050. This could cut national carbon emissions by 15 per cent compared to the present mix of electricity generation. Small-scale generation has the added benefit of avoiding distribution losses, which account for some 10 per cent of the electricity fed into the national grid. Conclusion The issue of energy supply has yet again come to the fore for many countries including Britain. A significant concern is that energy imports frequently come from countries about which there are various concerns. In March 2006, J. M. Barroso lead the European Commission to take its first shot at creating an EU energy policy. He argued that the EU could no longer afford 25 different and unco-ordinated energy policies. It will be interesting to see how this situation develops in years to come.