can pragmatic competence be taught?

advertisement

NFLRC NetWork #6

CAN PRAGMATIC COMPETENCE BE TAUGHT?

Gabriele Kasper

University of Hawai`i

Please cite as...

© 1997 Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center

'Can Pragmatic Competence Be Taught?' The simple answer to the question as formulated is "no". Competence,

whether linguistic or pragmatic, is not teachable. Competence is a type of knowledge that learners possess,

develop, acquire, use or lose. The challenge for foreign or second language teaching is whether we can arrange

learning opportunities in such a way that they benefit the development of pragmatic competence in L2. This, then,

is the issue I will address in this paper.

The pragmatic component in models of communicative competence

There are many definitions of pragmatics around. One I find particularly useful has been

proposed by David Crystal. According to him, "Pragmatics is the study of language from the

point of view of users, especially of the choices they make, the constraints they encounter

in using language in social interaction and the effects their use of language has on other

participants in the act of communication" (Crystal 1985, p. 240). In other words, pragmatics

is the study of communicative action in its sociocultural context. Communicative action

includes not only speech acts - such as requesting, greeting, and so on - but also

participation in conversation, engaging in different types of discourse, and sustaining

interaction in complex speech events. Following Leech (1983), I will focus on pragmatics as

interpersonal rhetoric - the way speakers and writers accomplish goals as social actors

who do not just need to get things done but attend to their interpersonal relationships with

other participants at the same time.

Leech (1983) and his colleague Jenny Thomas (1983) proposed to subdivide pragmatics into

a pragmalinguistic and sociopragmatic component. Pragmalinguistics refers to the resources

for conveying communicative acts and relational or interpersonal meanings. Such resources

include pragmatic strategies like directness and indirectness, routines, and a large range of

linguistic forms which can intensify or soften communicative acts. For one example,

compare these two versions of apology - the terse 'I'm sorry' and the Wildean 'I'm

absolutely devastated. Can you possibly forgive me?' In both versions, the speaker

apologizes, but she indexes a very different attitude and social relationship in each of the

apologies (e.g., Fraser, 1980; House & Kasper, 1981; Brown & Levinson, 1987; BlumKulka, House, & Kasper, 1989).

Sociopragmatics was described by Leech (1983, p. 10) as 'the sociological interface of

pragmatics', referring to the social perceptions underlying participants' interpretation and

performance of communicative action. Speech communities differ in their assessment of

speaker's and hearer's social distance and social power, their rights and obligations, and the

degree of imposition involved in particular communicative acts (Takahashi & Beebe, 1993;

Blum-Kulka & House, 1989; Olshtain, 1989). The values of context factors are negotiable;

they can change through the dynamics of conversational interaction, as captured in Fraser's

(1990) notion of the 'conversational contract' and in Myers-Scotton's Markedness Model

(1993).

Pragmatic ability in a second or foreign language is part of a nonnative speakers (NNS)

communicative competence and therefore has to be located in a model of communicative

ability (Savignon, (1991, for overview). In Bachman's model (1990, p. 87ff), 'language

competence' is subdivided into two components, 'organizational competence' and 'pragmatic

competence'. Organizational competence comprises knowledge of linguistic units and the

rules of joining them together at the levels of sentence ('grammatical competence') and

discourse ('textual competence'). Pragmatic competence subdivides into 'illocutionary

competence' and 'sociolinguistic competence'. 'Illocutionary competence' can be glossed as

'knowledge of communicative action and how to carry it out'. The term 'communicative

action' is often more accurate than the more familiar term 'speech act' because

communicative action is neutral between the spoken and written mode, and the term

acknowledges the fact that communicative action can also be implemented by silence or

non-verbally. 'Sociolinguistic competence' comprises the ability to use language

appropriately according to context. It thus includes the ability to select communicative acts

and appropriate strategies to implement them depending on the current status of the

'conversational contract' (Fraser, 1990).

Need L2 pragmatics be taught?

As Bachman's model makes clear, pragmatic competence is not extra or ornamental, like

the icing on the cake. It is not subordinated to knowledge of grammar and text organization

but co-ordinated to formal linguistic and textual knowledge and interacts with

'organizational competence' in complex ways. In order to communicate successfully in a

target language, pragmatic competence in L2 must be reasonably well developed. But

adopting pragmatic competence as one of the goals for L2 learning does not necessarily

imply that pragmatic ability requires any special attention in language teaching. Before

turning to the central question of my talk, i.e., whether L2 pragmatics can be taught, I will

therefore address the logically prior question of whether L2 pragmatics needs to be taught.

Because perhaps pragmatic knowledge simply develops alongside lexical and grammatical

knowledge, without requiring any pedagogic intervention.

Indeed, adult NNS do get a considerable amount of L2 pragmatic knowledge for free. This is

because some pragmatic knowledge is universal, and other aspects may be successfully

transferred from the learners' L1. To start with the pragmatic universals, learners know

that conversations follow particular organizational principles - participants have to take

turns at talk, and conversations and other speech events have specific internal structures.

Learners know that pragmatic intent can be indirectly conveyed, and they can use context

information and various knowledge sources to understand indirectly conveyed meaning.

They know that recurrent speech situations are managed by means of conversational

routines (Coulmas, 1981; Nattinger & DeCarrico, 1992) rather than by newly created

utterances. They know that strategies of communicative actions vary according to context

(Blum-Kulka, 1991); specifically, along such factors as social power, social and

psychological distance, and the degree of imposition involved in a communicative act, as

established in politeness theory (Brown & Levinson, 1987; Brown & Gilman, 1989).

Learners have demonstrated knowledge of the directive and expressive speech acts that

have been most frequently studied in cross-cultural and interlanguage pragmatics, such as

requests and apologies, and they have been shown to understand and use the major

realization strategies for such speech acts. For instance, in requesting, users of any

language studied thus far distinguish different levels of directness; direct, as in 'feed the

cat', conventionally indirect, as in 'can/could/would you feed the cat?', and indirect, as in

'the cat's complaining.' Furthermore, language users know that requests can be softened or

intensified in various ways, as in 'I was wondering if you would terribly mind feeding the

cat', and that requests can be externally modified through various supportive moves, for

instance justifications, as in 'I have to go to a conference', or imposition minimizers, as in

'She only needs food once a day'. Studies document that these strategies of requesting are

available to ESL or EFL learners who are NS of such diverse languages as Chinese

(Johnston, Kasper, & Ross, 1994), Danish (Færch & Kasper, 1989), German (House &

Kasper, 1987), Hebrew (Blum-Kulka & Olshtain, 1986), Japanese (Takahashi & DuFon,

1989), Malay (Piirainen-Marsh, 1995), and Spanish (Rintell & Mitchell, 1989). In their early

learning stages, learners may not be able to use such strategies because they have not yet

acquired the necessary linguistic means, but when their linguistic knowledge permits it,

learners will use the main strategies for requesting without instruction.

Learners may also get very specific pragmalinguistic knowledge for free if there is a

corresponding form-function mapping between L1 and L2, and the forms can be used in

corresponding L2 contexts with corresponding effects. For instance, the English modal past

as in the modal verbs could or would has formal, functional and distributional equivalents in

other Germanic languages such as Danish and German - the Danish modal past kunne/ville

and the German subjunctive könntest and würdest. And sure enough, Danish and German

learners of English transfer ability questions from L1 Danish (kunne/ville du låne mig dine

noter) and L1 German (könntest/ würdest Du mir Deine Aufzeichnungen leihen) to L2

English (could/would you lend me your notes) (House & Kasper, 1987; Færch & Kasper,

1989), and they do this without the benefit of instruction.

Positive transfer can also facilitate learners' task in acquiring sociopragmatic knowledge.

When distributions of participants' rights and obligations, their relative social power and the

demands on their resources are equivalent in their original and target community, learners

may only need to make small adjustments in their social categorizations (Mir, 1995).

Unfortunately, learners do not always make use of their free ride. It is well known from

educational psychology that students do not always transfer available knowledge and

strategies to new tasks. This is also true for some aspects of learners' universal or L1based pragmatic knowledge. L2 recipients often tend towards literal interpretation, taking

utterances at face value rather than inferring what is meant from what is said and

underusing context information. Learners frequently underuse politeness marking in L2

even though they regularly mark their utterances for politeness in L1 (Kasper, 1981).

Although highly context-sensitive in selecting pragmatic strategies in their own language,

learners may underdifferentiate such context variables as social distance and social power

in L2 (Fukushima, 1990; Tanaka, 1988).

So, the good news is that there is a lot of pragmatic information that adult learners possess,

and the bad news is that they don't always use what they know. There is thus a clear role

for pedagogic intervention here, not with the purpose of providing learners with new

information but to make them aware of what they know already and encourage them to use

their universal or transferable L1 pragmatic knowledge in L2 contexts.

The most compelling evidence that instruction in pragmatics is necessary comes from

learners whose L2 proficiency is advanced and whose unsuccessful pragmatic performance

is not likely to be the result of cultural resistance or disidentification strategies (Kasper,

1995, for discussion). In a study of a large sample of advanced ESL learners, Bouton (1988)

examined how well these students understood different types of indirect responses, or

implicature, as in the following dialog:

Sue: How was your dinner last night?

Anne: Well, the food was nicely presented.

Bouton found that in 27% of the cases, implicatures were understood differently by native

speakers (NS) and NNS. A re-test of 30 students after 4 1/2 years demonstrated that their

comprehension now showed a success rate of over 90%. But some implicature types

resisted improvement through exposure alone. These included the Pope question (as in Is

the Pope Catholic?) and indirect criticism as in the Sue & Anne dialogue. Students'

comprehension of implicature may thus profit from instruction, and as we will see shortly,

this has indeed proved to be the case.

Turning to production, candidates for pedagogic intervention can be sorted in four groups:

(1) choice of communicative acts, (2) the strategies by which an act is realized, (3) its

content, and (4) its linguistic form. Drawing on her and Beverly Hartford's data from

academic advising sessions (Bardovi-Harlig & Hartford 1990, 1993), Bardovi-Harlig (1996)

noted that NNS students tended to leave suggestions about their coursework to their

advisor and then react to them. Consequently, the NNS performed more rejections of

advisor suggestions than the NS students, who were more initiative in making suggestions

and thereby avoided rejections. Both NS and NNS regularly offered explanations when they

rejected their advisor's course suggestion, but the NS would also suggest alternatives ('how

about I take x course instead'), something the NNS never did. For their rejections, the NNS

sometimes used inappropriate content, such as claiming the course suggested by their

advisor was either too easy or too difficult, or even evaluating their advisor's course as

'uninteresting'. Finally, even at the end of the observation period, the NNS had not learnt

how to mitigate their suggestions and rejections appropriately. By using mitigating forms

such as 'I was thinking' or 'I have an idea... I dont' know how it would work out, but...', the

NS would cast their suggestions in tentative terms. By contrast, the NNS tended to

formulate their suggestions much more assertively, as in 'I will take language testing' or

'I've just decided on taking the language structure' (all examples from Bardovi-Harlig, 1996,

22f.).

Two things need to be emphasized in assessing the implications of Bouton's and BardoviHarlig and Hartford's studies. First, the participating advanced students were ESL learners,

yet the target environment either did not provide students with the input they needed, or

they did not notice it. Secondly, the recorded differences in NS and NNS pragmatic

comprehension and production may lead to serious miscommunication and compromise the

NNS's goals. Bardovi-Harlig and Hartford (1990) found that when students' contributions

were pragmatically inappropriate, they were less successful in obtaining their advisor's

consent for taking the courses they preferred.

A further aspect of students' pragmatic competence is their awareness of what is and is not

appropriate in given contexts. Bardovi-Harlig and Dörnyei (1997) reported that Hungarian

and Italian EFL learners recognized grammatically incorrect but pragmatically appropriate

utterances more readily than pragmatically inappropriate but grammatically correct

utterances, and this was true for learners of all proficiency levels. This finding strongly

suggests that without a pragmatic focus, foreign language teaching raises students'

metalinguistic awareness, but it does not contribute much to develop their metapragmatic

consciousness in L2.

Can L2 pragmatics be taught?

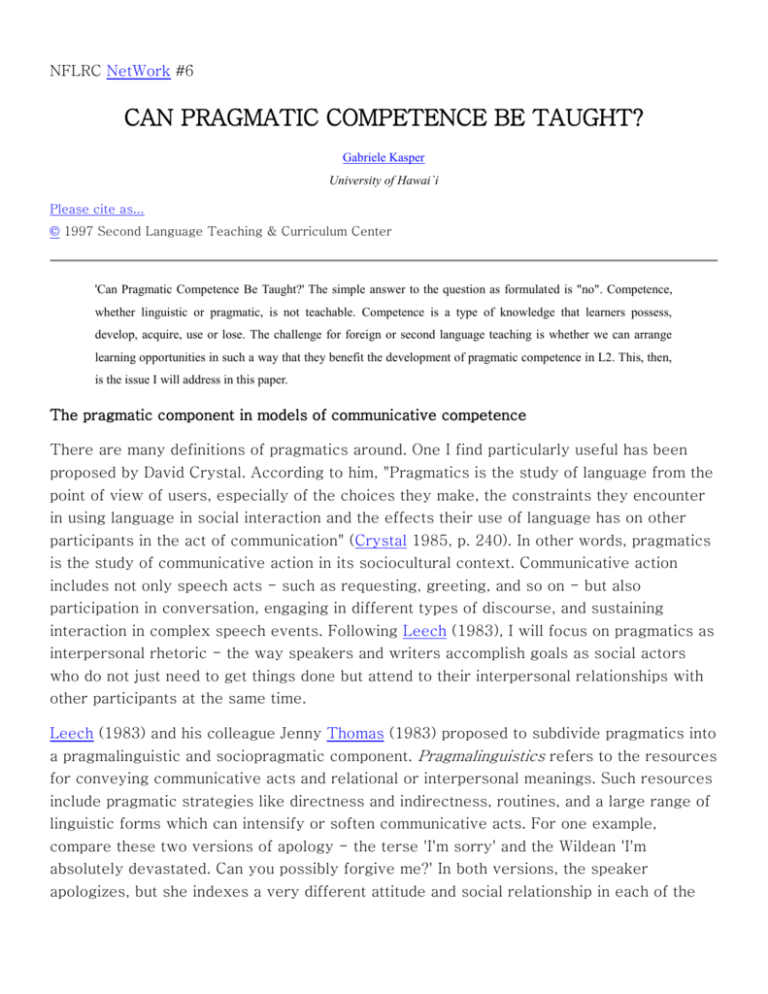

As we have seen, then, without some form of instruction, many aspects of pragmatic competence do not develop sufficiently. We

therefore need to know what pragmatic aspects can be taught and which instructional approaches may be most effective. Table 1

summarizes the data-based research on pragmatic instruction.

Table 1: Studies examining the effect of pragmatic instruction

study

teaching goal

proficiency

languages

research goal

design

assessment/

procedure/

instrument

House & Kasper

1981

discourse

markers &

strategies

advanced

L1 German FL

English

explicit vs

implicit

pre-test/ post-test

control group L2

baseline

roleplay

Wildner-Bassett

1984, 1986

pragmatic

routines

intermediate

L1 German FL

English

eclectic vs

suggesto-pedia

pre-test/ post-test

control group

roleplay

Billmyer 1990

compliment

high intermediate

L1 Japanese SL

English

+/-instruction

pre-test/ post-test

control group L2

baseline

elicited

conversation

Olshtain &

Cohen 1990

apology

advanced

L1 Hebrew FL

English

teachability

pre-test/ post-test

L2 baseline

discourse

completion

question.

Wildner-Bassett

1994

pragmatic

routines &

strategies

beginning

L1 English SL

German

teachability to

beginning FL

students

pre-test/ post-test

question-naires

roleplay

Bouton 1994

implicature

advanced

L1 mixed SL

English

+/-instruction

pre-test/ post-test

control group

multiple choice

question

pre-test/ post-test/

deductive vs

delayed post-test

inductive vs zero

control group

multiple choice

& sentence

combining

question

Kubota 1995

implicature

intermediate

L1 Japanese FL

English

House 1996

pragmatic

fluency

advanced

L1 German FL

English

explicit vs

implicit

Morrow 1996

complaint &

refusal

intermediate

L1 mixed SL

English

teachability/

explicit

Tateyama et al.

1997

pragmatic

routines

beginning

L1 English FL

Japanese

explicit vs

implicit

pre-test/ post-test

control group

roleplay

pre-test/ post-test/

roleplay holistic

delayed post-test

ratings

L2 baseline

pre-test/ post-test

control group

multi-method

All of the 10 studies report on classroom-based research on pragmatics. I excluded studies

conducted in a lab type situation because I wanted to make sure that the chosen approaches

are ecologically valid in actual L2 classrooms.

As you can see from the second column to the left, the teaching goals in these studies

extend over a large range of pragmatic features and abilities. Some studies examine the

discourse markers and strategies by which conversationalists get in and out of

conversations, introduce, sustain, and change topics, organize turn-taking and keep the

conversation going by listener activities such as backchanneling. Many of these

conversational activities are implemented by pragmatic routines which regularly occur in

spoken discourse, yet foreign language learners may have little exposure to them. A

number of discourse markers and strategies are illustrated in the following conversational

sequence.

A telephone conversation (Sacks, 1995, vol. II, p. 201f; transcript slightly modified)

A: Hello.

B: Vera?

A: Ye:s.

B: Well you know, I had a little difficulty getting you. (1.0) First I got the wrong number,

and then I got Operator, [A: Well.] And uhm (1.0) I wonder why.

A: Well, I wonder too. It uh just rung now about uh three ti//mes.

B: Yeah, well Operator got it for me.

A: She did.

B: Uh huh. So //uh

A: Well.

B: When I- after I got her twice, why she [A: telephoned] tried it for me. Isn't that funny?

A: Well it certainly is.

B: Must be some little cross of lines someplace hh

A: Guess so.

B: Uh huh,uh, am I taking you away from yer dinner?

A: No::. No, I haven't even started tuh get it yet.

B: Oh, you have//n't.

A: hhheh heh

B: Well I- I never am certain, I didn't know whether I'd be m too early or too late // or riA: No::. No, well I guess uh with us uhm there isn't any - [B: Yeah.] p'ticular time.

Another group of studies explores whether students benefit from instruction in specific

speech acts. So far, speech acts examined are compliments, apologies, complaints, and

refusals. There is a research literature on all of these speech acts, documenting how they

are performed by native speakers of English in different social contexts. Based on this

literature, students were taught the strategies and linguistic forms by which the speech acts

are realized and how these strategies are used in different contexts. As one example,

consider the realization strategies (or 'speech act set') for apologies (adapted from BlumKulka, House, & Kasper, 1989):

Apologetic formula: I'm sorry, I apologize, I'm afraid

Assuming Responsibility: I haven't read your paper yet.

Account: I had to prepare my TESOL plenary.

Offer of Repair: But I'll get it done by Wednesday.

Appeaser: Believe me, you're not the only one.

Promise of forbearance: I'll do better after TESOL.

Intensifier: I'm terribly sorry, I really tried to squeeze it in.

Bringing together the ability to carry out speech acts and manage ongoing conversation, House (1996) examined instructional effects

on what she calls pragmatic fluency - the extend to which students' conversational contributions are relevant, polite, and overall

effective. And finally, while most studies focus on aspects of production, two studies examined pragmatic comprehension: in Bouton

(1994), students were taught different types of implicatures, as in the Sue & Anne dialogue quoted earlier, and Kubota (1995)

replicated Bouton's study in an EFL context.

Whereas most of these pragmatic features were taught to intermediate or advanced

learners, participants in Wildner-Bassett (1994) and Tateyama et al. (1997) were beginning

learners. These two studies thus address the important question of whether pragmatics is

teachable to beginners or whether there needs to be some threshold of linguistic L2

competence first.

Wildner-Bassett's (1994) and Tateyama et al.'s studies are also the only ones in which the

target language is not English - in Wildner-Bassett's study, the L2 is German, in Tateyama

et al., it is Japanese. Note that in some studies, the target language is a foreign language

whereas in others, it is a second language. This has consequences for the learning

outcomes, as I will show a bit later.

The studies differed in their research goals. Olshtain and Cohen (1990), Wildner-Bassett

(1994) and Morrow (1996) explored whether the features under investigation were

teachable at all. These studies did not employ control groups but compared students' test

performance before and after instruction to that of NS of the target language, referred to as

'L2 baseline' in the 'design' column in Table 1. Billmyer (1990) and Bouton (1994) examined

whether students who received instruction in complimenting and implicature did better than

controls who did not. Yet another group explored the effectiveness of specific teaching

approaches. In these studies, two or more student groups received different types of

instruction. House and Kasper (1981), House (1996), and Tateyama et al. (1997) compared

explicit with implicit approaches. Explicit teaching involved description, explanation, and

discussion of the pragmatic feature in addition to input and practice, whereas implicit

teaching included input and practice without the metapragmatic component. WildnerBassett (1984, 1986) compared an eclectic approach with a modified version of

suggestopedia, and Kubota (1995) compared an inductive approach, where students had to

figure out in groups how implicatures in English work, to a teacher-directed deductive

approach and zero instruction in implicature. Information about the designs and assessment

procedures and instruments is provided in the two rightmost columns in Table 1, but I'm not

going to comment on those. Instead, let's proceed to the findings of the studies.

First of all, the studies that examined whether the selected pragmatic features were

teachable found this indeed to be the case, and comparisons of instructed students with

uninstructed controls reported an advantage for the instructed learners. Secondly, the

studies comparing the relative effect of explicit and implicit instruction found that students'

pragmatic abilities improved regardless of the adopted approach, but the explicitly taught

students did better than the implicit groups. Thirdly, with respect to other teaching

approaches, Wildner-Bassett (1984, 1986) found that both the eclectively taught students

and the suggestopedic group improved their use of conversational routines considerably,

however the eclectic group outperformed the suggestopedic group. Kubota (1995) reported

an advantage for students receiving either deductive or inductive instruction over the

uninstructed group, with a superior effect for the inductive approach, this initial difference

had evaporated by the time a delayed post-test was administered.

Wildner-Bassett (1994) and Tateyama et al. (1997) demonstrated that pragmatic routines

are teachable to beginning foreign language learners. This finding is important in terms of

curriculum and syllabus design because it dispels the myth that pragmatics can only be

taught after students have developed a solid foundation in L2 grammar and vocabulary. As

we know from uninstructed first and second language acquisition research, most language

development is function-driven - i.e., the need to understand and express messages

propels the learning of linguistic form. Just as in uninstructed acquisition, students can start

out by learning pragmatic routines which they cannot yet analyze but which help them cope

with recurrent, standardized communicative events right from the beginning.

There is little evidence for aspects of L2 pragmatics that resist development through

teaching, but the few documented cases are instructive. One such study is Kubota's

replication of Bouton's (1994) research on the teaching of implicature. Kubota's Japanese

EFL learners were able to understand the exact implicatures that were repeated from the

training materials but were unable to generalize inferencing strategies to new instances of

implicature. However, these students' English proficiency was much less advanced than that

of the learners in Bouton's studies, and with more time, occasion for practice, and increased

L2 input, the students' success rate might have improved.

The other study that suggests limitations to teachability in L2 pragmatics is House's (1996)

investigation on improving the pragmatic fluency of advanced German EFL students. All but

one feature of pragmatic fluency gained from consciousness raising and conversational

practice; the resistent aspect was to provide appropriate rejoinders, or second pair parts, to

an interlocutor's preceding contribution, as in this exchange:

NS: Oh I tell you what we go shopping together and buy all the things [we need]

NNS: [Of course] of course

NS: Okay then and you try and call Anja and ask her if she knows somebody who owns a grill

NNS: Yes of course (House, 1996, p. 242)

More appropriate acceptances of the NS' suggestions would have been 'ok/good idea/let's

do it that way then' or the like. Why would inappropriate rejoinders persist in these

advanced learners' discourse despite instruction? A plausible explanation is Bialystok's

(e.g., 1993) notion of control of processing: fluent and appropriate conversational responses

require high degrees of processing control in utterance comprehension and production, and

such complex skills may be very hard to develop through the few occasions for practice

that foreign language classroom learning provides.

But despite those few limitations, the research supports the view that pragmatic ability can

indeed be systematically developed through planful classroom activities. In order to address

the next question How can language instruction help develop pragmatic competence?

- we need to consider for a moment what opportunities for pragmatic learning are offered by traditional forms of language teaching.

L2 classrooms as impoverished learning environments

It is a well-documented fact that in teacher-fronted teaching, the person doing most of the talking is the teacher (e.g., Chaudron,

1988, for various analyses of teacher talk). This is to the detriment of students' speaking opportunities, but it could be argued that

through the sheer quantity of teacher talk, students are provided with the input they need for pragmatic development. However,

studies show that compared to conversation outside instructional settings, teacher-fronted classroom discourse displays

a more narrow range of speech acts (Long, Adams, McLean, & Castaños, 1976)

a lack of politeness marking (Lörscher & Schulze, 1988)

shorter and less complex openings and closings (Lörscher, 1986; Kasper, 1989)

monopolization of discourse organization and management by the teacher (Lörscher, 1986; Ellis, 1990), and consequently,

a limited range of discourse markers (Kasper, 1989).

The reason for such differences is not that classroom discourse is 'artificial'. Classroom discourse is just as authentic as any other

kind of discourse. Rather, classroom interaction is an institutional activity in which participants' roles are asymmetrically distributed

(Nunan, 1989), and the social relationships in this unequal power encounter are reflected and re-affirmed at the level of discourse.

Teacher's and students' rights and obligations, and the activities associated with them, are epitomized in the basic interactional

pattern of traditional teacher-fronted teaching - the (in)famous pedagogical exchange of elicitation (by the teacher) - response (by a

student) - feedback (by the teacher) (cf. discussion in Chaudron, 1988, p. 37). The classic scenario is consistent with a knowledgetransmission model of teaching, according to which the teacher imparts new information to students, helps them process such

information and controls whether the new information has become part of students' knowledge. Such functions can be implemented

through a very limited range of communicative acts.

If we map the communicative actions in classic language classroom discourse against the

pragmatic competence that nonnative speakers need to communicate in the world outside, it

becomes immediately obvious that the language classroom in its classical format does not

offer students what they need - not in terms of teacher's input, nor in terms of students'

productive language use. In a comparison of teacher-fronted teaching and small group

work, Long et al. (1976) demonstrated over 20 years ago that student participation

increases dramatically in student-centered activities. Importantly, student-centered

activities do more than just extend students' speaking time: they also give them

opportunities to practice conversational management, perform a larger range of

communicative acts, and interact with other participants in completing a task.

But despite its unique structure, even teacher-fronted classroom discourse offers some

opportunities for pragmatic learning. One important learning resource is classroom

management, because in this activity language does not function as an object for analysis

and practice but as a means for communication. If classroom management is performed in

the students' L1, they miss a valuable opportunity for experiencing the L2 as a genuine

means of communication. In a recent call for a role of students' native language in ESL

teaching, Auerbach (1993) proposed that classroom management is one of the activities that

could be carried out in students' L1 rather than the L2. Auerbach argues that using minority

students' native language for classroom management is one way of validating the students'

ethnolinguistic identity in an ESL classroom. In my view, Auerbach's call against English

Only classrooms in ESL settings for immigrant minorities is valid and necessary, but I want

to caution against extending it to EFL situations or any other foreign language classrooms,

for that matter. For students of English in Continental Europe or Asia, or students of

Japanese and French in the US, the FL classroom may be the only regular opportunity for

using the FL for communication. These opportunities should not be curtailed, and certainly

not when it comes to routinized activities such as classroom management discourse. In a

recent study of his learning of Japanese as a Foreign Language, Cohen (1997) reports:

"Classroom talk was focused primarily on completing a series of planned transactions, such as making

introductions, buying stamps or postcards at a post office, buying clothes in a department store, telling the doctor

about our illness, and the like. There was little non-transactional social conversation in class, other than asides in

English. In addition, spoken language tended to be focused on structures that we were to learn (...). Toward the end

of the second month, we would start the class off with teacher-directed questions and answers, usually inquiring

about what we had done the previous day or weekend, or what we intended to do - usually with the purpose of

practicing some structure or other."

Because little genuinly communicative interchange was conducted in Japanese, students had not much exposure to authentic input in

this classroom.

From the studies reviewed earlier and from other theory and research of SL learning, we

can distill a number of activities that are useful for pragmatic development. Such activities

can be classified into two main types: activities aiming at raising students' pragmatic

awareness, and activities offering opportunities for communicative practice.

Awareness-raising

Through awareness-raising activities, students acquire sociopragmatic and pragmalinguistic information - for instance, what function

complimenting has in mainstream American culture, what appropriate topics for complimenting are, and by what linguistic formulae

compliments are given and received. Students can observe particular pragmatic features in various sources of oral or written 'data',

ranging from native speaker 'classroom guests' (Bardovi-Harlig, et al., 1991) to videos of authentic interaction, feature films (Rose,

1997), and other fictional and non-fictional written and audiovisual sources.

Observation tasks

Especially in a second language context, students can be given a variety of observation assignments outside the classroom. Such

observation tasks can focus on sociopragmatic or pragmalinguistic features.

A sociopragmatic task could be to observe under what conditions native speakers of

American English express gratitude - when, for what kinds of goods or services, and to

whom (cf. Eisenstein & Bodman, 1993). Depending on the student population and available

time, such observations may be open or structured. Open observations leave it to the

students to detect what the important context factors may be. For structured observations,

students are provided with an observation sheet which specifies the categories to look out

for - for instance, speaker's and hearer's status and familiarity, the cost of the good or

service to the giver, and the degree to which the giver is obliged to provide the good or

service. A useful model for such an observation sheet is the one proposed by Rose (1994)

for requests.

A pragmalinguistic task focuses on the strategies and linguistic means by which thanking is

accomplished - what formulae are used, and what additional means of expressing

appreciation are employed, such as expressing pleasure about the giver's thoughtfulness or

the received gift, asking questions about it, and so forth. Finally, by examining in which

contexts the various ways of expressing gratitude are used, sociopragmatic and

pragmalinguistic aspects are combined. By focusing students' attention on relevant features

of the input, such observation tasks help students make connections between linguistic

forms, pragmatic functions, their occurrence in different social contexts, and their cultural

meanings. Students are thus guided to notice the information they need in order to develop

their pragmatic competence in L2 (Schmidt, 1993). The observations made outside the

classroom will be reported back to class, compared with those of other students, and

perhaps commented and explained by the teacher. These discussion can take on any kind of

small group of whole class format.

Whether gathered through out-of-class observation or brought into the classroom through

audiovisual media, authentic native speaker input is indispensible for pragmatic learning.

This is not because students should imitate native speakers' action patterns but in order to

build their own pragmatic knowledge on the right kind of input. Comparisons of textbook

dialogues and authentic discourse show that there is often a mismatch between the two. For

instance, Bardovi-Harlig, et al. (1991) examined conversational closings in 20 textbooks for

American English and found that few of them represented closing phases accurately.

Myers-Scotton and Bernstein (1988) discovered similar discrepancies between the

representation of many other conversational features in authentic discourse and textbook

dialogues. The reason for such inaccurate textbook representations is that native speakers

are only partially aware of their pragmatic competence (the same is true of their language

competence generally). As Wolfson (1989) noted, most of native speakers' pragmatic

knowledge is tacit, or implicit knowledge: it underlies their communicative action, but they

cannot describe it. Even the most proficient conversationalist has little conscious

awareness about turn-taking procedures and politeness marking. Miscommunication or

pragmatic failure is often vaguely diagnosed as 'impolite' behavior on the part of the other

person, whereas the specific source of the irritation remains unclear. Because native

speaker intuition is a notoriously unreliable source of information about the communicative

practices of their own community, it is vital that teaching materials on L2 pragmatics are

research-based (Myers-Scotton & Bernstein, 1988; Wolfson, 1989; Olshtain & Cohen,

1991; Bardovi-Harlig, et al., 1991).

Authentic L2 input is essential for pragmatic learning, but it does not secure successful

pragmatic development. When students' observe L2 communicative practices, their minds

don't simply record what they hear and see like a videocamera does. Students' experiences

are interpretive rather than just registering. Cognitive psychology (e.g., Sanford & Garrod,

1981) as well as radical constructivism (e.g., von Glaserfeld, 1995) emphasize the

importance of prior knowledge for comprehension and learning. In our attempt to

understand the practices of an unfamiliar community, we tend to view such practices

through the lenses of our own customs. We tend to classify experiences into 'familiar' and

thus not requiring further reflection or analysis, and 'unfamiliar', i.e., peculiar, enigmatic,

inviting explanation, and attracting evaluation. Müller (1981) referred to this interpretive

strategy as cultural isomorphism. As a strategy for the acquisition of everyday knowledge,

cultural isomorphism is a combination of assimilation and spot-the-difference. L2 practices

are subjected to the same social evaluations as the apparently equivalent L1 practices. The

resulting perspective is that of a tourist who sorts experiences in the visited country into

'just like home' and 'strange'. As Elbeshausen and Wagner (1985) comment, "Tourism is not

educational but it dramatically increases our repertoire of anecdotes" (p. 49), and this is

because through the assimilative and contrastive strategy of isomorphism, stereotypical

evaluations of L2 practices emerge. Language teaching therefore has the important task to

help students situate L2 communicative practices in their sociocultural context and

appreciate their meanings and functions within the L2 community. The research literature

on cross-cultural pragmatics documents the rich intracultural variation of communicative

action patterns and thus offers compelling counter-evidence against unhelpful and often

mutual stereotypes. For example, a stereotype held by some Japanese learners of English is

that Americans have a very direct style of communication (Tanaka, 1988; Robinson, 1992);

however, research on requests (Blum-Kulka & House, 1989; Blum-Kulka, 1991) and

refusals (Beebe, Takahashi, & Uliss-Weltz,, 1990; Beebe & Cummings, 1996) provides

evidence to the contrary.

Practicing L2 pragmatic abilities

Turning to students options for practicing their L2 pragmatic abilities, such practice requires student-centered interaction. In their

books on tasks for language learning, Nunan (1989) and Crookes and Gass (1993a, b) explain the rationale underlying a task-based

approach from the perspectives of second language acquisition and pedagogy. Most small group interaction requires that students

take alternating discourse roles as speaker and hearer, yet different types of task may engage students in different speech events and

communicative actions. It is therefore important to identify very specifically which pragmatic abilities are called upon by different

tasks. A useful distinction can be made between referential and interpersonal communication tasks. In referential communication

tasks (Yule, in press), students have to refer to concepts for which they lack necessary L2 words. Such tasks expand students'

vocabulary and develop their strategic competence. Interpersonal communication tasks are more concerned with participants' social

relationships and include such communicative acts as opening and closing conversations, expressing emotive responses as in

thanking and apologizing, or influencing the other person's course of action as in requesting, suggesting, inviting, and offering.

Activities such as roleplay, simulation, and drama engage students in different social roles and speech events. Such activities provide

opportunities to practice the wide range of pragmatic and sociolinguistic abilities (Crookall & Saunders, 1989; Crookall & Oxford,

1990; Olshtain & Cohen, 1991) that students need in interpersonal encounters outside the classroom.

Reconsidering pragmatic ability as a teaching goal

The purpose of the proposed learning activities is to help students become more effective and successful communicators in L2. But

what exactly does 'effective' and 'successful' mean? In conclusion of this paper, I will briefly re-examine the goals that instruction in

pragmatics should aim for.

First, it may be useful to remind ourselves that NS are no ideal communicators. As

Coupland, Wiemann, and Giles, (1991, p. 3) comment, "language use and communication are

(...) pervasively and even intrinsically flawed, partial, and problematic". And yet, by and

large NS communication succeeds more than it fails - not because it is perfect but because

it is good enough for the purpose at hand. It would be unreasonable and unrealistic to place

higher demands on L2 learners' communicative abilities than on those of NS. Therefore,

there is a continued need for studies examining how NS and NNS communicate effectively

in different contexts.

Secondly, there often appears to be an implicit understanding that effective and successful

NNSs have the same or very similar pragmatic ability as NS. On this view, pragmatic

competence as a learning objective should be based on a NS model. However, as Siegal

(1996) points out, "Second language learners do not merely model native speakers with a

desire to emulate, but rather actively create both a new interlanguage and an accompanying

identity in the learning process" (1996, p. 362ff) Second language learners' desire for

convergence with NS pragmatics or divergence from NS practices is shaped by learners'

views of themselves, their social position in the target community and in different contexts

within the wider L2 environment, and by their experience with NS in various encounters.

Thirdly, members of the target community may perceive NNS's total convergence to L2

pragmatics as intrusive and inconsistent with the NNS's role as outsider to the L2

community, whereas they may appreciate some measure of divergence as a disclaimer to

membership. Giles, Coupland, and Coupland (1991) documented that in many ethnolinguistic

contact situations, successful communication is a matter of optimal rather than total

convergence. Optimal convergence is a dynamic, negotiable construct that defies hard-andfast definition. It refers to pragmatic and sociolinguistic choices which are consistent with

participants' subjectivities and social claims, and recognizes that such claims may be in

conflict between participants.

Fourthly, as Peirce (1995) noted, language classrooms provide an ideal arena for exploring

the relationship between learners' subjectivity and L2 use. Classrooms afford second

language learners the opportunity to reflect on their communicative encounters and to

experiment with different pragmatic options. For foreign language learners, the classroom

may be the only available environment where they can try out what using the L2 feels like,

and how more or less comfortable they are with different aspects of L2 pragmatics. The

sheltered environment of the L2 classroom will thus prepare and support learners to

communicate effectively in L2. But more than that, by encouraging students to explore and

reflect their experiences, observations, and interpretations of L2 communicative practices

and their own stances towards them, L2 teaching will expand its role from that of language

instruction to that of language education.

References

Auerbach, E. R. (1993). Reexamining English Only in the ESL classroom. TESOL Quarterly, 27, 9-32.

Bachman, L. (1990). Fundamental considerations in language testing. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Bardovi-Harlig, K. (1996). Pragmatics and language teaching: Bringing pragmatics and pedagogy together. In L. F. Bouton (Ed.),

Pragmatics and language learning Vol. 7 (pp. 21-39). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Dörnyei, Z. (1997). Pragmatic awareness and instructed L2 learning: An empirical investigation. Paper

presented at the AAAL 1997 Conference, Orlando, March.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Hartford, B. S. (1990). Congruence in native and nonnative conversations: Status balance in the academic

advising session. Language Learning, 40, 467-501.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., & Hartford, B. (1993). Learning the rules of academic talk: A longitudinal study of pragmatic development.

Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 15, 279-304.

Bardovi-Harlig, K., Hartford, B.A.S., Mahan-Taylor, R., Morgan, M. J., & Reynolds, D.W. (1991). Developing pragmatic

awareness: Closing the conversation. ELT Journal, 45, 4-15.

Beebe, L. M., & Cummings, M. C. (1996). Natural speech act data versus written questionnaire data: How data collection method

affects speech act performance. In S. M. Gass & J. Neu (Hg.), Speech acts across cultures (pp. 65-86). Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

(Original version 1985).

Beebe, L. M., Takahashi, T., & Uliss-Weltz, R.(1990). Pragmatic transfer in ESL refusals. In R. C. Scarcella, E. Andersen, & S. D.

Krashen (Eds.), Developing communicative competence in a second language (55-73). New York: Newbury House.

Bialystok, E. (1993). Symbolic representation and attentional control in pragmatic competence. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka

(Eds.), Interlanguage pragmatics (pp. 43-59). New York: Oxford University Press.

Billmyer, K. (1990). "I really like your lifestyle": ESL learners learning how to compliment. Penn Working Papers in Educational

Linguistics, 6:2, 31-48.

Blum-Kulka, S. (1991). Interlanguage pragmatics: The case of requests. In R. Phillipson, E. Kellerman, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood

Smith, & M. Swain (Eds.), Foreign/ second language pedagogy research (pp. 255-272). Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Blum-Kulka, S. & House, J. (1989). Cross-cultural and situational variation in requestive behavior in five languages. In S. BlumKulka, J. House, & G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics (pp. 123-154). Norwood, NJ: Ablex

Blum-Kulka, S., House, J., & Kasper, G. (Eds.). (1989). Cross-cultural pragmatics: Requests and apologies. Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Blum-Kulka, S., & Olshtain, E. (1986). Too many words: Length of utterance and pragmatic failure. Studies in Second Language

Acquisition, 8, 47-61.

Bouton, L. (1988). A cross-cultural study of ability to interpret implicatures in English. World Englishes, 17, 183-196.

Bouton, L. F. (1994). Conversational implicature in the second language: Learned slowly when not deliberately taught. Journal of

Pragmatics, 22, 157-67.

Brown, P. & Levinson, S. (1987). Politeness: Some universals in language usage. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brown, R., & Gilman, A. (1989). Politeness theory and Shakespeare's four major tragedies. Language in Society, 18, 159-212.

Canale, M., & Swain, M. (1980). Theoretical bases of communicative approaches to second language teaching and testing. Applied

Linguistics, 1, 1-47.

Carrell, P. L. (1979). Indirect speech acts in ESL: Indirect answers. In C. A. Yorio, K. Perkins, & J. Schachter (Eds.), On TESOL '79

(pp. 297-307). Washington, D.C.: TESOL.

Chaudron, C. (1988). Second language classrooms. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Cohen, A. (1997). In search of pragmatic competence: Insights from intensive study of Japanese. Paper presented at ESL Lecture

Series, University of Hawai`i, February.

Coulmas, F. (Ed.). (1981). Conversational routine. The Hague: Mouton.

Coupland, N., Wiemann, J.M., & Giles, H. (1991). Talk as "problem" and communication as "miscommunication": An integrative

analysis. In N. Coupland, H. Giles, & J.M. Wiemann (Eds.), "Miscommunication" and problematic talk (pp. 1-17). Newbury Park:

Sage.

Crystal, D. (1985). A dictionary of linguistics and phonetics. 2nd. edition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Crookall, D., & Oxford, R. (Eds.) (1990). Simulation, gaming, and language learning. New York: Newbury House.

Crookall, D., & Saunders, D. (Eds.) (1988). Communication and simulation. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Crookes, G., & Gass, S.M. (Eds.) (1993a). Tasks and language learning. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Crookes, G., & Gass, S.M. (Eds.) (1993b). Tasks in a pedagogical context. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Eisenstein, M., & Bodman, J. (1993). Expressing gratitude in American English. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.),

Interlanguage pragmatics (pp. 64-81). New York: Oxford University Press.

Elbeshausen, H., & Wagner, J. (1985). Kontrastiver Alltag - Die Rolle von Alltagsbegriffen in der interkulturellen Kommunikation.

In J. Rehbein (Ed.), Interkulturelle Kommunikation (pp. 42-59). Tübingen: Narr.

Ellis, R. (1990). Instructed second language acquisition. Oxford: Blackwell.

Færch, C.,& Kasper, G. (1989). Internal and external modification in interlanguage request realization. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House,

& G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics (pp. 221-247). Norwood, N. J.: Ablex.

Fraser, B. (1990).Perspectives on politeness. Journal of Pragmatics, 14, 219-236.

Fukushima, S. (1990). Offers and requests: Performance by Japanese learners of English. World Englishes, 9, 317-325.

Giles, H., Coupland, J., & Coupland, N. (Eds.). (1991). Contexts of accommodation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

House, J. (1996). Developing pragmatic fluency in English as a foreign language: Routines and metapragmatic awareness. Studies in

Second Language Acquisition, 18, 225-252.

House, J. & Kasper, G. (1981). Zur Rolle der Kogni-tion in Kommunikationskursen. Die Neueren Sprachen, 80, 42-55.

House, J., & Kasper, G. (1987). Interlanguage pragmatics: Requesting in a foreign language. In W. Lörscher & R. Schulze (Eds.),

Perspectives on language in performance. Festschrift for Werner Hüllen (pp. 1250-1288). Tübingen: Narr.

Johnston, B., Kasper, G., & Ross, S. (1994). Effect of rejoinders in production questionnaires. University of Hawai`i Working Papers

in ESL, Vol. 13. No. 1, 121-143.

Kasper, G. (1981). Pragmatische Aspekte in der Interimsprache. Tübingen: Narr.

Kasper, G. (1989). Interactive procedures in interlanguage discourse. In W. Oleksy (Ed.), Contrastive pragmatics (pp. 189-229).

Amsterdam: Benjamins.

Kasper, G. (1992). Pragmatic transfer. Second Language Research, 8, 203-231.

Kasper, G. (1995). Wessen Pragmatik? Für eine Neubestimmung fremdsprachlicher Handlungskompetenz. Zeitschrift für

Fremdsprachenforschung, 6, 1-25. Kasper, G., & Schmidt, R. (1996). Developmental issues in interlanguage pragmatics. Studies in

Second Language Acquisition, 18, 149-169.

Kitao, K. (1990). A study of Japanese and American perceptions of politeness in requests. Doshida Studies in English, 50, 178-210.

Koike, D. A. (1989). Pragmatic competence and adult L2 acquisition: Speech acts in interlanguage. Modern Language Journal, 73,

79-89.

Kubota, M. (1995). Teachability of conversational implicature to Japanese EFL learners. IRLT Bulletin, 9. Tokyo: The Institute for

Research in Language Teaching, 35-67.

Leech, G. (1983). Principles of pragmatics. London: Longman.

Lörscher, W. (1986). Conversational structures in the foreign language classroom. In G. Kasper (Ed.), Learning, teaching and

communication in the foreign language classroom (pp. 11-22). Århus: Aarhus University Press.

Lörscher, W., & Schulze, R. (1988). On polite speaking and foreign language classroom discourse. International Review of Applied

Linguistics in Language Teaching, 26, 183-199.

Long, M. H., Adams, L., McLean, M., & Castaños, F. (1976). Doing things with words - Verbal interaction in lockstep and small

group classroom situations. In Brown, H.D., Yorio, C. A., & Crymes, R. H. (Eds.), Teaching and learning English as a second

language: Trends in research and practice (pp. 137-153). Washington, DC: TESOL.

Mir, M. (1995). The perception of social context in request performance. In L.F. Bouton & Y. Kachru (Eds.), Pragmatics and

language learning monograph series, Vol. 6 (pp. 105-120). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Morrow, C. K. (1996). The pragmatic effects of instruction on ESL learners' production of complaint and refusal speech acts.

Unpublished PhD dissertation, State University of New York at Buffalo.

Müller, B. D. (1981). Bedeutungserwerb - ein Lernprozess in Etappen. In B.D. Müller (Ed.), Konfrontative Semantik (pp. 113-154).

Weil der Stadt: Lexika.

Myers-Scotton, C. (1993). Social motivations for codeswitching. Oxford: Clarendon.

Myers-Scotton, C., & Bernstein, J. (1988). Natural conversation as a model for textbook dialogue. Applied Linguistics, 9, 372-384.

Nattinger, J. R. & DeCarrico, J. S. (1992). Lexical phrases and language teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Nunan, D. (1989). Designing tasks for the communicative classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Olshtain, E. (1989). Apologies across languages. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House, & G. Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics (pp.

155-173). Norwood, NJ: Ablex.

Olshtain, E., & Cohen, A.D. (1990). The learning of complex speech act behavior. TESL Canada Journal, 7, 45-65.

Olshtain, E., & Cohen, A.D. (1991). Teaching speech act behavior to nonnative speakers. In M. Celce-Murcia (Ed.), Teaching

English as a second or foreign language (pp. 154-165. Boston, MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Peirce, B. N. (1995). Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29, 9-31.

Piirainen-Marsh, A. (1995). Face in second language conversation. Jyväskylä: University of Jyväskylä.

Rintell, E., & Mitchell, C. J. (1989). Studying requests and apologies: An inquiry into method. In S. Blum-Kulka, J. House, & G.

Kasper (Eds.), Cross-cultural pragmatics (pp. 248-272). Norwood, N.J.: Ablex.

Robinson, M. A. (1992). Introspective methodology in interlanguage pragmatics research. In G. Kasper (Ed.), Pragmatics of

Japanese as native and target language. Technical Report # 3 (pp. 27-82), Second Language Teaching & Curriculum Center,

University of Hawai`i at Manoa.

Rose, K. R. (1994). Pragmatic consciousness-raising in an EFL context. In L.F. Bouton & Y. Kachru (Eds.), Pragmatics and

language learning monograph series, Vol. 5 (pp. 52-63). Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Rose, K. R. (1997). Pragmatics in the classroom: Theoretical concerns and practical possibilities. In L.F. Bouton (Ed.), Pragmatics

and language learning Vol. 8 Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Sacks, H. (1995). Lectures on conversation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Sanford, A. J., & Garrod, S. C. (1981). Understanding written language. Chichester, NY: Wiley.

Savignon, S. (1991). Communicative language teaching: State of the art. TESOL Quarterly, 25, 261-277.

Schmidt, R. (1993). Consciousness, learning and interlanguage pragmatics. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka (Eds.), Interlanguage

pragmatics (pp. 21-42). New York: Oxford University Press.

Siegal, M. (1996). The role of learner subjectivity in second language sociolinguistic competency: Western women learning

Japanese. Applied Linguistics, 17, 356-382.

Takahashi, T., & Beebe, L. M. (1993). Cross-linguistic influence in the speech act of correction. In G. Kasper & S. Blum-Kulka

(Eds.), Interlanguage pragmatics (pp. 138-157). New York: Oxford University Press.

Takahashi, S., & DuFon, M. A. (1989). Cross-linguistic influence in indirectness: The case of English directives performed by native

Japanese speakers. Unpublished manuscript, Department of English as a Second Language, University of Hawai`i at Manoa (ERIC

Document Reproduction Service No. ED 370 439)

Tanaka, N. (1988). Politeness: Some problems for Japanese speakers of English. JALT Journal, 9, 81-102.

Tateyama, Y., Kasper, G., Mui, L., Tay, H., & Thananart, O., (1997). Explicit and implicit teaching of pragmatics routines. In L.

Bouton (Ed.), Pragmatics and language learning, Vol. 8. Urbana, IL: University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Thomas, J. (1983). Cross-cultural pragmatic failure. Applied Linguistics, 4, 91-112.

von Glaserfeld, E. (1995). A constructivist approach to teaching. In L. P. Steffe & J. Gale (Eds.), Constructivism in education (pp. 315). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

Wildner-Bassett, M. (1984). Improving pragmatic aspects of learners' interlanguage. Tübingen: Narr.

Wildner-Bassett, M. (1986). Teaching 'polite noises': Improving advanced adult learners' repertoire of gambits. In G. Kasper (Ed.),

Learning, teaching and communication in the foreign language classroom (pp. 163-178). Århus: Aarhus University Press.

Wildner-Bassett, M. (1994). Intercultural pragmatics and proficiency: 'Polite' noises for cultural appropriateness. International

Review of Applied Linguistics, 32, 3-17.

Wolfson, N. (1989). Perspectives: Sociolinguistics and TESOL. New York: Newbury House.

Yule, G. (1996). Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Yule, G. (in press). Referential communication tasks. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum.

back to NFLRC NetWork #6