4.2 Organizational architecture

advertisement

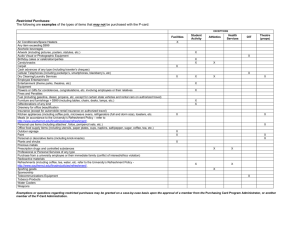

The Performance Effects of Organizational Architecture Antonio Davila Professor of Entrepreneurship and Accounting and Control IESE Business School University of Navarra and Mahendra Gupta Professor Olin School of Business Washington University in St. Louis and Richard J. Palmer* Professor 260 Dempster Hall, MS 5815 Department of Accounting Harrison College of Business Southeast Missouri State University One University Plaza Cape Girardeau, MO 63701 Phone: (573)-651-2908 E-Mail: rpalmer@semo.edu * Please direct correspondence to Professor Palmer. Special thanks to David Rhoads for his assistance with the analysis in this paper 1 The Performance Effects of Organizational Architecture Abstract Balancing the three components of organizational architecture—decision rights, performance measurement system, and reward system—is a key element in organizational design. Top managers that fail to manage these variables are predicted to face lower performance. Two lines of theoretical accounting research have examined the interdependence among these three variables. Responsibility accounting has focused on the joint design of decision rights and reward system, while measurement theory has studied the relationship between measurement system characteristics and reward system. The concept of organizational architecture brings these two lines of research together. However, little empirical evidence exists on the predicted relationship between organizational architecture and performance. This study brings initial evidence on this important empirical question. A unique database on the implementation of corporate purchasing card programs—a new financial tool to reduce transaction costs—allows us to compare the performance of several organizational architectures. We find that a particular organizational architecture outperforms the rest. This architecture combines delegation, intense performance measurement, and performance-based rewards and is consistent with an optimal design in the presence of information asymmetry. While the optimal organizational architecture found in this study is consistent with extant theory, the diminution of performance by organizations with sub-optimal organizational configurations appears to deviate from expectations. Our findings generally indicate that each successive addition of a “high performing” component of organizational architecture adds incrementally to elevate the performance. This “Hawthorne” type effect may indicate that managers are loathe to ignore the organizational priorities reflected in the organization’s investment of time and resources into either measuring performance, establishing rewards, or formulating appropriate delegations of authority. 2 The Performance Effects of Organizational Architecture 1. Introduction A key component in defining the management process is the allocation of decision rights associated with the resources of the firm (Jensen and Meckling 1992). Decision rights, together with performance evaluation and reward systems, define the concept of organizational architecture (Brickley, Smith et al. 1995; Brickley et al. 2003). These three variables are predicted to jointly interact to affect organizational performance. The design of the reward systems must consider the decision rights delegated to the agent and the information captured through the measurement systems. Similarly, the design of the measurement system depends on the allocation of decision rights. If one of these variables changes, the other two also have to change in order to maintain the right balance (Zimmerman 1999), otherwise organizational performance deteriorates. Organizations where information asymmetry among hierarchical levels is significant are more likely to allocate decision rights to those agents with specific knowledge (Jensen and Meckling 1992). However, the concept of organizational architecture predicts that delegation alone is not sufficient (Jensen and Wruck 1994). Delegation of decision rights has to be matched with a measurement system that tracks the performance of the agent and a reward system that minimizes agency costs. This concept of organizational architecture brings together two significant bodies of theoretical accounting research. The first one is “measurement theory” research (Banker and Datar 1989; Feltham and Xie 1994). This literature holds decision rights constant to highlight the interdependence between measurement systems and the design of incentive contracts. The second body of research is responsibility accounting 3 (Melumad and Reichelstein 1987; Melumad, Mookherjee et al. 1992; Baiman and Rajan 1995). This research stresses the importance of delegation (allocation of decision rights) to the design of the design of incentive contracts, holding constant the performance measurement system’s characteristics. Organizational architecture highlights the need for an adequate performance measurement system to fully characterize the interdependence between decision rights and incentive contracts. Empirical research has followed from these two lines of research. A sizeable body of empirical research has focused on the relationship between performance measurement and incentive contracts (Lambert and Larcker 1988; Bushman, Smith et al. 1996; Ittner, Larcker et al. 1997; Rankin and Sayer 2000). The overall conclusion from these studies is consistent with theoretical predictions associating noisiness, informativeness, and congruency with reward system design. In contrast, empirical research capturing allocation of decision rights is scarcer because of the difficulty to find adequate data (Nagar 2002). Once allocation of decision rights is included in the empirical specification, the three components of organizational architecture become internal to organizations. The data required is typically not publicly available and difficult to compare across firms because of differences in organizational design. Previous empirical work more closely related to this study includes Nagar (2002) and Widener et al.(2008). Nagar (2002) examines two of the three components of organizational architecture consistent with the responsibility accounting literature; this is allocation of decision rights and reward systems. Based on a professional survey of retail banks, he finds that these two variables are simultaneously determined. Widener et al. (2008) extend this finding to include performance measurement—the third component of organizational architecture. Using a survey-based research design with a sample of 53 4 Internet firms, they find that the three components of organizational architecture are interdependent and that the structural relations are complementary. This study extends the empirical literature on organizational architecture. In particular, it examines the prediction that decision rights, performance measurement, and reward system interact to affect performance. This research question requires a setting where organizations are still experimenting with different organizational architectures. This experimentation insures that certain organizational architectures are not designed optimally and thus correlated with performance. We capitalize on the introduction of a relatively new financial tool—corporate purchasing cards (hereafter, p-cards)—and a proprietary database to examine this research question. Our database includes a cross-sectional sample of organizations that have implemented p-card programs. Financial institutions that issue these cards require a program manager as a contact person in each organization; this requirement facilitates cross-sectional comparison across the organizational architecture that different firms implement. The database stems from a detailed survey from the leading market research company in p-card technology conducted in 2010. We use the concept of organizational architecture to explain the cross-sectional variance in the performance of p-card programs. We find that firms are using different organizational architectures to implement their p-card programs, consistent with experimentation that goes with new technologies before the optimal architecture is found. We also find that organizational architecture affects the performance of p-card programs. In particular, the p-card programs at organizations that delegate decision rights to the pcard program manager and match this allocation of decision rights with performance measurement and rewards perform significantly better. This finding is consistent with 5 information asymmetry characterizing p-card programs and requiring delegation of decision rights. However, this allocation of decision rights is only effective if properly balanced with the other two components of organizational architecture. The reminder of the paper is structured as follows. Section 2 provides a theoretical discussion of allocation of decision rights, performance measurement, and incentive contracts. Section 3 describes the database, while section 4 describes the research variables, and model specification. Section 5 presents the results and section 6 concludes. 2. Theory Top management needs to address the information asymmetry that emerges when agents have specific knowledge relevant to the management of the firm. One alternative is to move this knowledge up to the principal who has the decision rights. However, this alternative may be costly and the best solution is to allocate decision rights to the agent with private information (Melumad and Reichelstein 1987; Melumad, Mookherjee et al. 1992; Baiman and Rajan 1995). Delegation matches decision rights with the location of specific knowledge in the organization and increases the impact of the agent’s decisions upon the principal’s objective function. In other words, the productivity of the agent’s effort increases with delegation. This solution is not without cost and the principal has to bear the agency costs associated with the moral hazard problem induced. To minimize agency costs, delegation is implemented together with an incentive contract that matches the decision rights delegated to the agent (Melumad, Mookherjee et al. 1992). The incentive contract is intended to motivate the manager to exert effort congruent with the principal’s objectives. Principal-agent theory indicates that as the productivity of the 6 agent’s effort increases, other things equal, the weight of performance measures on the incentive contract increases. Nagar (2002) provides evidence consistent with this predicted relationship between delegation and the extent of incentive compensation. Another line of theoretical accounting research has examined the relationship between performance measurement and incentive contracts. In contrast with the responsibility accounting research, “measurement theory” research assumes allocation of decision rights as given to focus on the characteristics of performance measurement systems. This literature provides relevant insights to understand how incentive contracts vary with the quality of the measurement system. This quality is reflected in two main characteristics. The first one is captured by the concept of signal-to-noise ratio (Banker and Datar 1989). In particular, the weight of a performance measure in a compensation contract is directly proportional to its sensitivity and inversely proportional to its noisiness. The second characteristic that affects the quality of a measurement system is its congruency—its ability to properly capture and weight the different measures of the agent’s performance (Holmstrom and Milgrom 1991; Feltham and Xie 1994). The prediction derived from these models indicates a positive relationship between the quality of the measurement system and the extent of incentive compensation. The empirical evidence is consistent with this prediction (Lambert and Larcker 1988; Bushman, Smith et al. 1996; Ittner, Larcker et al. 1997). Bushman, Injejikian et al. (2000) provide a theoretical model where delegation and performance measurement are examined within a linear-contracting framework. These authors investigate the value of delegation as a function of the nature of the agent’s private information in the presence of an imperfect measure of agent’s performance. 7 These three key variables in accounting research have also been brought together through the concept of organizational architecture (Brickley, Smith et al. 1995; Brickley, Smith et al. 2003). This concept captures the interdependencies highlighted in the previous two research literatures and indicates that the three variables need to match each other. In particular, delegation of decision rights requires incentive contracts that motivate the agent to exert effort commensurate with the decision rights that have been allocated to him, as well as a performance measurement system with information characteristics that facilitate the structure of these contracts. Failure to properly match the three components of organizational architecture is reflected in lower performance. The impact on performance rests on the assumption that some organizations have not selected their best organizational architecture and, consequently, they do not behave optimally. This assumption is not uncommon in previous empirical research. For example, a highly debated question in the CEO compensation literature is the relationship between incentive contract design and firm performance (Murphy 1985; Baker, Jensen et al. 1988; Tosi and Gomez-Mejia 1989; Leonard 1990; Hubbard and Palia 1995; Hall and Liebman 1998). Such an out-of-equilibrium behavior is more likely to be relevant for new business processes where firms are still experimenting with alternative organizational architectures. Information asymmetry is the variable that theoretical models identify as driving the need to delegate. Delegating decision rights may be the best organizational structure when the private information is costly to move through the hierarchy. Private information may be costly because of motivational reasons—the cost to the principal of motivating the agent to reveal it is too high (Melumad, Mookherjee et al. 1992)—or because of its nature—the information is specific knowledge and therefore difficult to 8 code and transmit (Jensen and Meckling 1992). Once delegation is found to be the optimal organizational structure, the other two variables of organizational structure have to match this delegation. In particular, delegation requires a reward system more sensitive to performance because the impact of the agent’s decision and effort on the process is larger. It also requires a more detailed measurement system where performance measures are linked to the reward system. Such a system has better measurement characteristics—signal to noise ratio and congruity—and thus enhances the effectiveness of the reward system. 3. Data Our database provides information on the various organizational architectures that companies have adopted to implement a new payment technology known as purchasing cards as well as on the success that companies have had in implementing the technology. P-cards are a bank commercial card technology product designed to increase the efficiency of the procure-to-payment business cycle by enabling employee-cardholders to charge purchases for which the company agrees to pay in full within an agreed upon number of days. Cardholders receive a monthly statement and are assigned a monthly and a transactional credit limit. Unlike personal credit cards, the company is obligated to pay one bill that summarizes monthly purchases made by all cardholders. This process reduces or eliminates all activities and paperwork previously required to process these purchases including approvals, requisitions, purchase orders, invoices, and payment (Palmer et al., 1996). 9 The use of p-cards remains a relatively new phenomenon in the marketplace. Pcards were developed in the late 1980’s as a means to help federal government agencies acquire goods without subjecting their vendors to the long wait for payment associated with government bureaucracy at that time (Herbst-Murphy, 2011). Use of purchasing cards moved to the private sector in the mid-1990’s. Their relevance stimulated a rich accounting practice literature with anecdotal evidence of on-going corporate experimentation regarding the appropriate management practices to optimize and control the purchasing card goods acquisition process that continues to this day (see, for example, Fitzgerald 2009; Gamble 1996; Hamel 2009; Larson, 2010; Martinson 2002). Notwithstanding on-going experimentation, key structural elements of organizational use of p-cards are comparable across organizations. For example, card issuers require a contact person who is responsible for the daily activities of the p-card program. Within the card-using organization this person is commonly known as the purchasing card administrator (PCA). The purchasing process based on p-cards is reasonably standardized, with employees having pre-approved spending limits on their cards, using their cards to purchase goods from suppliers, and the company paying a consolidated monthly bill. Thus, the goods acquisition process as enabled by p-cards is self-contained and comparable across a cross-section of firms, yet with variance in terms of the organizational architecture and performance. The data comes from a survey administered by a leading market research firm in bank commercial card technology. The firm developed the survey working together with credit card brands and participating financial institutions. An extensive design process insured that the main issues associated with p-cards were appropriately addressed and that the questions were both clear and concise. The final survey—a benchmark study—was designed to be 10 comprehensive in order to be of the highest value to the participants. The final survey was 29 pages and the expected completion time was 2 to 4 hours. Data from the survey is published widely and used by both financial institutions and business and governmental entities to describe “norms” of organizational use of p-cards. An initial mailing of 2,364 surveys was made to mid-size to large organizational purchasing card-using customers of nineteen major banks that issue MasterCard and/or Visa products. Sixty-hundred and seventy-two responses were received (28.3%). Because instructions indicated that the respondent could skip a question if the answer was not known, some survey questions have responses that are 1% to 12% fewer than the sample response. The sample includes a wide mix of organizations in terms of industry composition, size and purpose (for profit, not-for-profit). Table 1 provides descriptive statistics on the sample and industry breakdown. -----------------------------Insert Table 1 ------------------------------ 4 Research variables 4.1 P-card performance measures The chief objective of p-card program is to reduce transaction costs by streamlining and improving the administrative efficiency of the purchasing process. Transactional cost saving are derived, in part, from the impact that p-cards have on the manpower required to conduct work activities using the traditional purchase-order driven process to acquire and pay for goods and services (including sourcing, vendor communications, and activities and approvals needed to process requisitions, purchase orders, receiving documents, invoices, and checks). Some transactional cost savings 11 attributable to purchasing cards may be “soft.” Soft savings occur when the level of transaction activity shifted to p-cards reduces the administrative workload but not in a manner sufficient to enable the elimination of personnel. By contrast, “hard” savings occur when the administrative workload reduction, driven by shifting higher levels of transaction activity to p-cards, supports the elimination of personnel in the Purchasing and Accounts Payable functional areas. Consequently, we use two measures of organizational performance of the p-card program. The first measure of p-card program performance is the estimated percentage of low-value (under $2,500) transactions that are paid by p-cards.1 For the second measure, we asked respondents to provide both the number of people currently employed in Accounts Payable and Purchasing and the additional number of people that would need to be hired in those areas if the p-card was removed from the organization. From their responses, we created a measure of the percentage of workforce reduction in Purchasing/AP due to the p-card program as a correlative approach to measuring the success of the p-card program (to wit, a surrogate for “hard savings”). 4.2 Organizational architecture Our unit of analysis is the p-card program administrator (PCA). Accordingly, the design of the organizational architecture converges in the decision rights, the performance measurement, and the compensation system of this person. Decision rights. Aside from oversight of administrative details, the primary role of the PCA is to improve organizational efficiency by facilitating the organizational shift from 1 Low value transactions are the typical target for purchasing card payment because some controls associated with the traditional purchasing process can be relaxed or eliminated for transactions of lower financial risk. Further, organizations rarely pay for low-value purchases by means other than paper-based check or card technology. Payments via ACH, EFT, or wire transfers are primarily restricted to larger dollar purchases. Consequently, this percentage reflects a movement away from paper to electronic payment. 12 paper-based to electronic transaction processing methods. The decision rights allocated to the PCA relate to his/her ability to distribute or influence the distribution of p-cards and assign or influence the assignment of appropriate monthly and per transaction limits for cardholders in light of employee spending needs and organizational borrowing constraints. Further, absent vocal top management support, employees given p-cards may be hesitant about or resist card use (as is common with any new technology). Research has shown that top management support is sine qua non to the success of managerial efforts to implement new technologies and processes within an organization (Howell and Higgins 1990; Day 1994). Hence, one must consider top management support of the PCA’s activities as an imprimatur legitimating the decision rights assigned to the administrator. Thus, we construct our measure of decision rights in several steps. First, we measure the organization’s total p-card line of credit (LOC), calculated by multiplying the number of cards in the organization by the average monthly spending limit. This construction is multiplied by twelve to annualize the spending authority. The LOC is then multiplied by two adjustment factors. The first adjustment factor reflects any impingement to the cardholder’s ability to acquire goods and services due to additional “per transaction” spending limits (75% of organization so limit card use in this manner). Practically speaking, the cardholder’s ability to utilize the full measure of his/her monthly spending limit is diminished if the maximum amount allowed for a transaction is low. Hence, we created a per transaction adjustment factor by multiplying the organization’s average per transaction spending limit by the organization’s average number of monthly transactions per card and then divided the product by the organization’s average monthly spending limit. In this way, if a cardholder cannot reach his/her monthly spending limit by transacting the “average” number of 13 transactions with his or her p-card, the monthly spending limit would be adjusted downward to reflect a “practical” spending authority.2 The practical spending authority is then adjusted by a simple measure to express the degree of top management support for the p-card program (and, by implication, the activities of the PCA). Top management support is measured by the degree of agreement (measured on a 7-point Likert scale) with the statement, “At my organization there is a top management sponsor who gives strong vocal support to the p-card program the through purchasing cards.”3 The numerator is then divided by the organization’s annual revenues (or budget, for government and not-for-profits entities) to adjust for organizational size, thus creating a measure of the allocation of spending authority expressed as a percentage of revenue (or annual budget). In mathematical summary, the decision rights (DECRIGHT) variable is defined as: (Monthly Line of Credit * 12) * (Per Transaction Adjustment Factor) x (Top Mgt. Support Factor) DECRIGHT = ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------Annual Sales Revenue (or Budget) 2 Assume, for example, an organization has an average monthly purchasing card spending limit of$10,000, a per transaction limit of $500, and 6 average monthly transactions per card. In this case, we multiply the monthly spending limit by 30% (($500 x 6)/$10,000) to reflect the practical limit in the delegation of spending authority imposed by the per transaction threshold. If, on the other hand, an organization had an average monthly purchasing card spending limit of$10,000 but a per transaction limit of $5,000, no adjustment was made to the monthly spending limit since the cardholder could reach his monthly spending limit in less than 6 transactions. 3 Where 1=do not agree, 7=fully agree. The factor is calculated by dividing respondents answer by 7. 14 Where the per transaction adjustment factor (PTAF) is expressed as: Respondent avg. per transaction spending limit x Respondent avg. number of transactions per card per month PTAF = -----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------Respondent average monthly spending limit where PTAF maximum ≤ 1.0. Performance measurement. The existence of performance measurement of the p-card program was measured by yes/no response to the question, “Does your organization use a measure or measures to evaluate purchasing card program performance?” If respondents indicated that p-card program performance was measured, a second set of questions asked about the type and importance of the performance measurement used for the job evaluation of the pcard manager. The importance of the performance metric is measured using a 7-point scale anchored from “very unimportant” (1) to “very important” (7), with an additional score of zero if the measure is not used. Eight measures are included: (1) number of transaction on pcards, (2) dollar amount of p-card purchases, (3) cardholder satisfaction with p-card program, (4) number of active cardholder accounts, (5) targeted percent of small dollar spending or transactions charged on p-card, (6) rebate paid by the card issuer, (7) percent of targeted vendors accepting p-cards, and (8) number of active cardholder accounts. Incentives. The structure of the reward system is measured using three 7-point scale items. The items asked the respondent to rate the impact of p-card program performance on the p-card manager’s (a) pay and bonuses, (b) promotions, and (c) obtaining of preferred future assignment(s). The responses were anchored from “no impact” (1) to “significant impact” (7). Principal component factor analysis extracted one factor. The Cronbach alpha reliability measure for the three variables is 0.89. We summed the scores on the three items to create the incentive variable. 15 4.3 Control variables In addition to the hypothesized variables, we control for additional variables that may affect the performance of the p-card program. We control for organizational size inasmuch as larger companies may present more complexities in implementing and administering pcard programs. This variable is proxied by the natural logarithm of the number of employees (Lnemp). We also control for the length of time since the p-card program was initiated in years (Program age). Initiatives that have been in place longer are expected to perform better as more managers and employees have gone down the learning curve associated with p-card use. Three other control variables reflect the potential impact of the type of organization, the internal controls related to card use that are employed at the organization, and different aspects of p-card training, discussed seriatum. Type of organization. Different types of organizations may see more or less value to p-cards as a method for streamlining the procure-to-pay cycle. Hence we controlled for respondent-identified organizational categorization. The organization types include (1) public corporations, (2) private corporations, (3) universities, (4) cities and counties, (5) state agencies, (6) federal agencies, (7) school districts, and (8) not-for-profit entities. Internal controls. The number and nature of internal controls utilized can positively or negatively impact employee use of the p-card and subsequent capture of low-value transactions on p-cards. We control for internal control practices by adding affirmative answers to eight questions related to training, including whether or not the organization: (1) requires users to maintain a logbook of card activity, (2) has a documented policy regarding receipt retention, (3) officially reprimands/disciplines cardholders that fail to submit receipts, (4) evaluates the spending patterns of cardholders who tend to have a high number of disputed transactions, (5) de-activates unused p-card accounts, (6) tracks and resolves 16 disputed transactions, (7) formally audits the spending approval process, and (8) conducts data mining of p-card transactions to identify potential misuse. We then counted the number of controls used by each organization to create the internal control variable. The eight questions constitute a single factor with a Cronbach alpha reliability measure of 0.52 and are included in Appendix A. Training. We control for training by adding affirmative answers to ten questions related to training, including whether or not the organization (1) provides easy access to a copy of the policies and procedures manual for p-card use to every p-card cardholder, (2) requires initial training of cardholders, (3) requires refresher training for cardholders, (4) provides “web-based” purchasing card training materials, (5) provides “in-person” purchasing card training, (6) provides “self-study” purchasing card training materials, (7) provides a Web site that answers p-card questions, (8) tracks completion of training and training updates by employees, (9) supports p-card program administrator attendance at “p-card user conferences” to identify new ways to use p-cards, and (10) has an ongoing method of communicating p-card information to cardholders and managers. In addition, an above median response of agreement to the statement “At my organization, a strong "business case" is made to employees about the benefits of p-cards (where 1= do not agree, 7=fully agree) added 1 to the training measure. The eleven questions constitute a single factor with a Cronbach alpha reliability measure of 0.72 and are included in Appendix A. 4.4 Statistical specification Theory predicts that organizations that optimally balance the three components of organizational architecture perform better. The argument hinges on organizations not having found the optimal equilibrium between decision rights, performance measurement, and 17 compensation system. For stable business processes that have been in place for a long time, such out-of-equilibrium argument may be too ambitious; but for p-card programs where organizations are still experimenting with different organizational architectures, such out-ofequilibrium is likely. Theory does not provide a unique prediction concerning the best combinations of these three variables. But if information asymmetry characterizes the p-card process, then theory indicates that allocating decision rights to the p-card manager may be the best organizational design. To be fully effective, delegation must come together with a compensation system that rewards good performance and detailed performance measures that provide the basis for an effective compensation system. This combination is expected to lead to better performance. To examine this hypothesis whether a particular combination of the three components leads to better performance, we divide the sample into four different groups. Groups are formed as follows. Observations for each component of organizational architecture— decision rights, performance measurement, and compensation—are split into high and low around the median. For example, firms with decision rights above the median are labeled high-decision rights and firms below to the median are labeled low-decision rights. Similarly, firms with performance measurement (compensation) above the median are labeled high-performance measurement (high-compensation) and below the median are labeled low-performance measurement (low-compensation). We identify organizations that are above the median for all three components as TripleHi. We identify a second group of organizations that score above the median for two out of the three components as DoubleHi. A third group that we label DoubleLo has one component above the median and two below the median. The fourth group, TripleLo, is companies that score below the median for all three components of organizational architecture. 18 To more closely examine whether a particular combination of the three variables leads to better performance, we further divide the sample into eight different groups. Groups are formed as follows. Observations for each variable are split into high and low around the median. For example, firms with decision rights above the median are labeled high-decision rights and firms below to the median are labeled low-decision rights. Similarly, firms with performance measurement (compensation) above the median are labeled high-performance measurement (high-compensation) and below the median are labeled low-performance measurement (low-compensation). The combination of these three different groupings leads to eight possible combinations which we identify with a dummy variable as follows: Status of Organizational Architecture Descriptor of Organizational Architecture TripleHi Decision Rights High Performance Evaluation High Rewards High HiPerfMeasRwds Low High High HiPerfMeasDecRights High High Low HiRwdsDecRights High Low High HiPerfMeas Low High Low HiRwds Low Low High HiDecRights High Low Low TripleLo Low Low Low Hence the statistical specification is: Perf = β0 + Σi (βi * groupi) + Σj γj * controlsj + ε Where β0 is the condition which the group members are low on all three factors (decision rights, performance evaluation, and incentives) and i varies from 1 to 7 for the 19 seven different groups, and the control variables include the age of the program, the logarithm of the number of employees, and measures of training and internal controls. We expect Triple Hi to perform better than the other combinations. We run the specification using an ordinary least squares model with performance as our dependent variable and dummy variables for each of the different groups while controlling for heteroskedasticity and outliers. 5. Results 5.1 Descriptive statistics Table 2 provides the descriptive statistics for the variables used in the research. Panel A provides background statistics on the organizations in the sample as well as pcard related statistics including monthly spending. The mean number of transactions per card per month is 10.13. The mean number of years that p-cards program has been in place is 6.7 years; 25% of the organizations have had the program for less than 3.5 years. This statistic reflects the fact that p-cards are still relatively new financial tools for some organizations. Panel A also shows that about half of PCAs indicate that p-card program performance will have little or no impact on pay and bonuses, promotions, or the obtaining of preferred future assignment (with median response reflecting an answer of -or “no impact”--to all three questions). Further, though not shown on Table 2, 49% of respondents indicated that their performance was evaluated against a performance metric. We will exploit the bifurcated nature of these two measures (they either have some reward or none, they are evaluated against some performance metric or not) to categorize our respondents into particular organizational architectures. Henceforth, high rewards 20 will be dummy coded with 1 if the PCA will receive some measure of reward if the pcard program does well and high performance measurement will be dummy coded with 1 if the PCA is evaluated against a performance measure. Panel B describes the performance of p-card programs. On average, 42.81% of under $2,500 transactions are paid with purchasing cards. Further, because the purchasing card eliminates work activities in both the Purchasing and AP functions, respondents (on average) report a 15.44% reduction in their AP/Purchasing headcount due to the use of purchasing cards. In terms of organizational architecture, Panel C reflects the discussion above, to wit: 49% of p-card program managers are evaluated against a performance metric and 41% indicate that their performance will have something other than “no impact” on pay and bonuses, promotions, or the obtaining of preferred future assignment. The calculation of the raw decision rights variable is discussed in section 4.2 above; the decision rights variable in Table C reflects a dummy coding of 1 to all respondents with a raw decision rights at or above the median. D reports descriptive statistics for the additional control variables. -----------------------------Insert Table 2 -----------------------------Table 3 reports the Pearson correlation coefficients for the dependent and independent variables under examination. Consistent with others who have examined organizational architecture and performance (e.g., Widener et al. 2008) the three elements of organizational architecture are significantly correlated. Further, both dependent variables (capture of under $2,500 transaction and headcount reduction) are correlated with each leg of architecture and with program age, internal control, and training. 21 -----------------------------Insert Table 3 -----------------------------Table 4 reports univariate statistics on performance for the four groups. The table shows a pattern of incrementally improved performance (for both dependent variables) whenever a “leg” or additional leg of positive organizational architectural is added. -----------------------------Insert Table 4 ------------------------------ 5.2 Main Results Table 5 presents the main results of the paper. The coefficient for the TripleHi group is positive and significant for both under $2,500 transaction capture and percentage headcount reduction, suggesting that organizations with the three components of organizational architecture aligned perform better than alternative organizational architectures. In the case of under $2,500 transaction capture on p-cards, the coefficients for both DoubleLo and DoubleHi groups are significant as well. The age of the program is positive and significant as expected. Size, as proxied by the natural logarithm of the number of employees, is negative for both dependent variables. As expected, training related to pcard use is positive and significant for both dependent variables. Neither internal control or the type of organization contribute significantly to explaining variability in the performance measures. -----------------------------Insert Table 5 ------------------------------ 22 Table 6 presents the F-statistics for the constraint of equal coefficients across pairs of groups. For both dependent variables, the coefficient for TripleHi is significantly different from the coefficient of the rest of the groups. Though less remarkable, for under $2,500 capture of transactions both DoubleHi and DoubleLo are significantly different from TripleLo and DoubleHi is significantly different than DoubleLo. For headcount reduction, DoubleHi is significantly different from both DoubleLo and TripleLo but DoubleLo is not significantly different than TripleLo. -----------------------------Insert Table 6 -----------------------------5.3 Extension As an alternative specification, we group the various organizations in eight rather than four groups. Table 7 reports univariate statistics on performance for the eight groups. As with the four groups, the table generally shows a pattern of incrementally improved performance (for both dependent variables) whenever a “leg” or additional leg of positive organizational architectural is added. However, not all legs of positive organizational architecture appear to have equal impact on performance. Organizations with high decision rights (HiDecRights) report a greater difference in under $2,500 capture and headcount reduction over TripleLo than organizations with rewards (HiRwds) or performance measurement (HiPerfMeas) only. Further, in all cases and across both dependent variables, organizations with two positive legs of organizational architecture report notably higher performance than organizations with any one positive leg. Finally, in all cases and across both dependent variables, organizations with all three positive legs of organizational architecture report notably higher performance than organizations with any other combination. 23 -----------------------------Insert Table 7 -----------------------------Again, each group is identified with a dummy variable and we include the same controls as in our main specification. Table 8 presents the results. -----------------------------Insert Table 8 -----------------------------TripleHi is significant with respect to the capture of under $2,500 transactions on the p-card and the percentage reduction in AP/Purchasing headcount. In addition, organizations with high decision rights (HiDecRights) and a combination of high decision rights and rewards (HiPerfMeasRwds) have a positive coefficient for under $2,500 transaction capture. Table 9 presents the F-statistics for the constraint of equal coefficients across pairs of groups. The performance of TripleHi organizations is significantly different than any other organizational architecture (at p<.10) for both dependent variables. Further, the performance of “double high” organizations (in whatever combination) is always significantly different than TripleLo (at p<.10%) for both dependent variables. However, the performance of “double high” organizations is higher than “single high” organizations (whether in relation to decision rights, performance measurement, or rewards) in only five of eighteen comparisons. Finally, the performance of organizations with high decision rights (HiDecRights) is significantly different than TripleLo, while organizations with rewards (HiRwds) and performance measurement (HiPerfMeas) are not. -----------------------------Insert Table 9 ------------------------------ 24 Finally, Table 10 provides covariate adjusted means. The conclusions are consistent with our previous results. -----------------------------Insert Table 10 -----------------------------6. Discussion Theoretical accounting research has identified allocation of decision rights, performance measurement systems, and rewards systems as interdependent. These three variables have been brought together under the concept of organizational architecture. According to the theory that has been developed around this concept, there is an optimal architecture. Organizations that deviate from the optimal are predicted to have lower performance. The results in this paper provide the first empirical evidence on this important research question. Based on a unique database, we find that organizations with higher delegation, a more developed measurement system, and a reward system linked to performance perform better. The superiority of this arrangement is consistent with a setting characterized by information asymmetry where delegation is superior to centralized decision making. Furthermore, it is consistent with the need to balance the three components of organizational architecture: delegation is effective only if a detailed measurement system and an appropriate reward system are in place. While the optimal organizational architecture found in this study is consistent with extant theory, the diminution of performance by organizations with sub-optimal organizational configurations appears to deviate from expectations. In particular, we expected that there would be no significant difference in the performance of organizations with sub-optimal organizational architectures (i.e., if any leg was removed from the stool, the 25 stool would fall). However, our findings generally indicate that each successive addition of a “high performing” component of organizational architecture (e.g., high decision rights) added incrementally to elevate the organizational performance outcome. Whether this result is an “Hawthorne effect” (Landsberger, 1958) artifact or some other phenomenon is a matter for future research and investigation. Arguably, organizational investment of time and resources into either measuring performance, establishing rewards, or formulating appropriate delegations of authority communicate organizational priorities which managers may be loathe to ignore. The study is subject to important caveats. First, the complexity of simultaneously capturing various organizational dimensions requires us to rely on perceptual data. The complexity of the relationship studied and the fact that respondents did not choose a certain organizational architecture over others suggest that perceptual bias does not drive the results; although this explanation cannot be ruled out. Second, the relationship between organizational architecture and performance relies on an out-of-equilibrium argument. This assumption has been maintained in several prior empirical studies and the significance of the results—consistent with theoretical predictions—suggests that the assumption may be valid. However, it is possible that organizations are selecting their organizational architecture and that the difference in performance is related to an omitted variable that affects the selection of a particular architecture and performance. Third, the study relies on a single work process. This research design feature facilitates the selection of a well-defined unit of analysis, but limits its generalizability. Fourth, missing observations reduced the number of data points significantly with larger organizations failing to complete relevant parts of the survey. This fact further reduces the ability to generalize the conclusions. 26 Despite these limitations, the study provides the first empirical evidence on the relevance of organizational architecture as a concept to explain organizational performance. This concept brings together two important theoretical accounting research literatures and the current study provides evidence that emphasizes their importance from an empirical perspective. 27 References Baiman, S. and M. Rajan (1995). “Centralization, delegation, and shared responsibility in the assignment of capital investment decision rights.” Journal of Accounting Research 33(Supplement): 135-164. Baker, G., M. Jensen, et al. (1988). “Compensation and incentives: Practice vs. theory.” Journal of Finance 43(3): 593-616. Banker, R. D. and S. M. Datar (1989). “Sensitivity, precision, and linear aggregation of signals for performance evaluation.” Journal of Accounting Research 27: 21-39. Brickley, J. A., C. W. Smith, et al. (1995). “The economics of organizational architecture.” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 8(2): 19-31. Brickley, J. A., C. W. Smith, and J. L. Zimmerman. 2003. Managerial Economics And Organizational Architecture, 3rd ed. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill. Bushman, R., R. Indjejikian, et al. (2000). “Private pre-decision information, performance measure congruity and the value of delegation.” Contemporary Accounting Research 17: 561-587. Bushman, R., A. Smith, et al. (1996). “CEO compensation: The role of individual performance evaluation.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 21(3): 161-194. Day, D. L. (1994). “Raising radicals: different processes for championing innovative corporate ventures.” Organization Science 5(2): 148-172. Feltham, G. A. and J. Xie (1994). “Performance measure congruity and diversity in multi-task principal/agent relations.” Accounting Review 69: 429-453. Fitzgerald, K. (2009). "Issuers say economic pain is the corporate card's gain." American Banker 174: 5. Gamble, R. (1996). "Overcoming p-card hurdles." Treasury and Risk Management 6: 1-5. Hall, B. J. and J. B. Liebman (1998). “Are CEOs really paid like bureaucrats?” The Quarterly Journal of Economics 113(3): 653-691. Hamel, D. (2009). "Parenting your p-card program." Government Procurement 17:10-11. Herbst-Murphy, S. (2011). "Getting down to business: Commercial cards in business-tobusiness payments. Discussion Paper, Payment Cards Center, Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelpia (March) 28 Holmstrom, B. and P. Milgrom (1991). “Multitask principal-agent analyses: Incentive contracts, asset ownership, and job design.” Journal of Law, Economics, and Organization 7: 24-52. Howell, J.M. and C.A. Higgins (1990). “Champions of technological innovations,” Administrative Science Quarterly 35: 317-341. Hubbard, R. and D. Palia (1995). “Executive pay and performance: Evidence from the US banking industry.” Journal of Financial Economics 39(1): 105-130. Ittner, C., D. Larcker, et al. (1997). “The choice of performance measures in annual bonus contracts.” Accounting Review 72: 231-255. Jensen, M. and W. Meckling (1992). Specific and general knowledge, and organizational structure. Contract economics. L. Werin and H. Wijkander. Oxford, Blackwell: 251-274. Jensen, M. C. and K. H. Wruck (1994). “Science, specific knowledge, and total quality management.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 18(3): 247-288. Lambert, R. and D. Larcker (1988). “An analysis of the use of accounting and market measures of performance in executive compensation contracts.” Journal of Accounting Research 29(1): 129-149. Landsberger, H. (1958). Hawthorne Revisited. Ithaca Press. Larson, L. (2010). "P-card program pitfalls and success strategies." Government Procurement 18: 10-11. Leonard, J. (1990). “Executive pay and firm performance.” Industrial and Labor Relations Review 43(3): S13-29. Martinson, B. (2002). "The power of the p-card." Strategic Finance 83(8): 30-35. Melumad, N., D. Mookherjee, et al. (1992). “A theory of responsibility centers.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 15: 445-484. Melumad, N. and S. Reichelstein (1987). “Centralization versus delegation and the value of communication.” Journal of Accounting Research 25(Supplement): 1-18. Murphy, K. J. (1985). “Corporate performance and managerial remunerations: An empirical analysis.” Journal of Accounting and Economics 7: 11-43. Nagar, V. (2002). “Delegation and incentive compensation.” Accounting Review 77(2): 379-395. Palmer, R., T. Schmidt, and J. Jordan-Wagner (1996). "Corporate procurement cards: The reengineered future for non-inventory purchasing and payables." Journal of Cost Management 10: 19-31. 29 Rankin, F. W.. and T L. Sayre (2000). The effects of performance separability and contract type on agent effort. Accounting, Organizations and Society 25: 683-95. Tosi, H. L. J. and L. R. Gomez-Mejia (1989). “The decoupling of CEO pay and performance: An agency theory perspective.” Administrative Science Quarterly 34: 169189. Widener, S.K., M.B. Shackell, and E.A. Demers (2008). “The juxtaposition of social surveillance controls with traditional organizational design components.” Contemporary Accounting Research 25(2): 605-638. Zimmerman, J. L. (1999). Accounting for Decision Making and Control. Boston, Irwin McGraw-Hill. 30 Table 1 Descriptive statistics Type of Organization Public corporation Private corporation University School district City or county State or Federal agency Other Not-for-Profit entity Total 158 149 90 63 113 47 52 672 * Note: 611 answered questions related to headcount reduction and 640 responded about purchasing card capture of under $2,500 transactions on the card. The 672 represents respondents who answered one or both questions. Industry of Corporate Respondents Agricultural, Mining, and Construction Finance, Insurance, Banking, and Real Estate Manufacturing Other Services Professional, Scientific, and Technical Services Software and IT Telecom, Media, and Entertainment Transportation, Warehousing, and Delivery Utilities Wholesale and Retail Total 37 25 103 12 22 11 20 19 17 41 307 31 Table 2 Descriptive statistics Panel A: Organization and program statistics Variable N Mean 25% percentile Median 75% percentile Standard deviation Sales (in $ millions) 672 2,657 122 375 1,500 8,192 Number of employees 672 7,280 575 1,721 6,000 17,189 Monthly spending total (in $ thousands) 672 1,268 113 350 1,125 3,337 Number of p-cards 672 757 75 204 600 1,927 Age of the p-card program 671 6.74 3.50 5.50 8.50 4.27 Monthly trans. per card 672 10.13 3.75 5.92 10.01 17.07 Monthly spend per card ($) 672 5,811 748 1,403 2,941 22,981 Reward system (unadjusted sum of three questions) 667 5.81 3.00 3.00 8.00 4.34 75% percentile Standard deviation Panel B: Program performance Variable N Mean 25% percentile Median Percentage of under $2,500 transactions paid by p-cards 664 42.81 15.00 35.00 70.00 32.02 Percentage reduction in AP/Purchasing Headcount 611 15.44 0.00 8.51 25.00 18.71 Panel C: Organizational architecture Variable N Mean 25% percentile Median 75% percentile Standard deviation Decision rights 672 0.50 0.0 0.50 1.0 0.50 Performance measure 672 0.49 0.0 0.0 1.0 .50 Rewards (0/1 variable) 672 0.41 0.0 0.0 1.0 .49 The decision rights variable is constructed as per description in text. High (median or above) decision rights are dummy coded with 1, all others assigned 0. Performance measure is the mean score of the nine measurement-related questions (7-point scale). Reward system is the mean score of the three compensationrelated questions (7-point scale). The Rewards variable is created by assigning 0 to all answers of 3 and 1 to any answer above 3 (indicating some measure of reward to PCA based on program performance). 32 Panel D: Organizational dynamics Variable N Mean 25% percentile Median 75% percentile Standard deviation Training 670 6.55 5.00 7.00 9.00 2.58 Internal control 656 .66 .50 .63 .88 .21 Training is the sum of affirmative answers to ten training-related questions plus 1 for an above median response to a Likert-scaled response to a question related to employee training. Internal control is the percentage of affirmative answers to eight internal control-related questions 33 Table 3 Pearson correlation coefficients for dependent and independent variables Under $2,500 Capture Headcount Reduction DecRights Under $2,500 Capture .23*** .23*** Headcount Reduction ----- DecRights Rewards Training Internal Control Program Age .14*** .11** .24*** .16*** .21*** .16*** .12** .16*** .22*** .04 .16*** ----- .10** .17*** .22*** .05 .20*** ----- 0.21*** 0.41*** .25*** .15*** ----- 0.29*** .10** .09* ----- .38*** .31*** ----- .20*** PerfMeas Rewards Training Internal Control Program Age PerfMeas ----- *, **, *** indicate significance at 5%, 1%, and .1% respectively. 34 Table 4 Descriptive statistics on performance Mean 25% percentile Median 75% percentile % of Under $2,500 Transactions Paid by P- Card TripleHi 0.57 0.30 0.60 0.80 DoubleHi 0.45 0.20 0.40 0.70 DoubleLo 0.40 0.10 0.30 0.60 TripleLo 0.31 0.10 0.20 0.45 TripleHi 0.24 0.07 0.20 0.33 DoubleHi 0.17 0.00 0.13 0.28 DoubleLo 0.13 0.00 0.05 0.22 TripleLo 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.17 % Reduction in AP/Purchasing Headcount TripleHi is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with all three systems of organizational architecture are at or above their respective sample medians. DoubleHi is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with two of the three systems of organizational architecture above their respective sample medians. DoubleLo is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with two of the three systems of organizational architecture below their respective sample medians. TripleLo is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with all three systems of organizational architecture below their respective sample medians. 35 Table 5 Regression results Variable Performance % of Under $2,500 Transactions Paid by % Reduction in P- Card AP/Purchasing Headcount (t-statistic) (t-statistic) Organizational structure TripleHi DoubleHi DoubleLo .172 (3.82) .086 (2.25) *** ** .095 *** (3.53) 0.033 (1.47) .070 (2.00) ** 0.016 (0.81) 0.011 (3.41) 0.005 (0.89) -0.018 (-2.14) 0.015 (2.56) 0.088 (1.35) 0.236 (3.26) *** -0.157 (-3.16) -0.027 (-0.63) -0.157 (-3.16) 0.033 (2.19) -0.003 (-0.72) 0.174 (3.80) Control variables Age of program Organizational type Ln(employees) Training Internal control Intercept Adjusted R2 (%) ** ** *** 10.50 8.68 F-statistic 9.01 6.94 N 622 592 *** *** ** *** *, **, *** indicate significance at 10%, 5%, and 1% respectively. 36 Table 6 Comparison of effects of alternative organizational structures TripleHi TripleHi DoubleHi 9.82 (0.00) DoubleHi 7.58 (0.00) DoubleLo 21.17 (0.00) 3.90 (0.05) TripleLo 27.08 (0.00) 8.44 (0.00) DoubleLo TripleLo 20.73 (0.00) 38.84 (0.00) 2.71 (0.10) 14.89 (0.00) 6.27 (0.01) 1.45 (0.23) The upper triangle reports the F-statistic and significance of constraining the coefficients to be equal for capture of under $2,500 transactions on purchasing cards. The lower triangle reports the same statistic for the percentage of headcount reduction experienced in AP and Purchasing functions due to use of the purchasing card. 37 Table 7 Descriptive statistics on performance Mean 25% percentile Median 75% percentile % of Under $2,500 Transactions Paid by P- Card TripleHi 0.57 0.30 0.60 0.80 HiPerfMeasRwds 0.41 0.15 0.30 0.60 HiPerfMeasDecRights 0.49 0.22 0.50 0.75 HiRwdsDecRights 0.46 0.20 0.50 0.65 HiPerfMeas 0.38 0.10 0.30 0.60 HiRwds 0.35 0.08 0.25 0.56 HiDecRights 0.45 0.20 0.40 0.60 TripleLo 0.31 0.10 0.20 0.45 TripleHi 0.24 0.07 0.20 0.33 HiPerfMeasRwds 0.18 0.04 0.13 0.23 HiPerfMeasDecRights 0.16 0.00 0.12 0.31 HiRwdsDecRights 0.17 0.00 0.14 0.28 HiPerfMeas 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.17 HiRwds 0.12 0.00 0.05 0.21 HiDecRights 0.15 0.00 0.08 0.25 TripleLo 0.11 0.00 0.00 0.17 % Reduction in AP/Purchasing Headcount TripleHi is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with all three systems of organizational architecture are at or above their respective sample medians. DoubleHi is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with two of the three systems of organizational architecture above their respective sample medians. DoubleLo is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with two of the three systems of organizational architecture below their respective sample medians. TripleLo is a dummy variable that takes value of one for companies with all three systems of organizational architecture below their respective sample medians. 38 Table 8 Regression results Performance Variable % of Under $2,500 Transactions Paid by P- Card (t-statistic) % Reduction in AP/Purchasing Headcount (t-statistic) Organizational structure 0.167 (3.70) 0.044 (.85) 0.106 (2.21) 0.092 (1.77) 0.038 (0.83) 0.030 (0.57) 0.113 (2.67) *** 0.010 (2.97) 0.004 (0.73) -0.013 (-1.50) *** 0.016 (2.61) 0.103 (1.57) 0.201 (2.68) *** TripleHi HiPerfMeasRwds HiPerfMeasDecRights HiRwdsDecRights HiPerfMeas HiRwds HiDecRights ** ** 0.093 (3.45) 0.044 (1.34) 0.021 (0.72) 0.037 (1.20) -0.000 (-0.01) 0.022 (0.67) 0.026 (1.07) *** 0.005 (2.69) -0.005 (-1.45) *** -0.013 (-2.44) 0.012 (3.32) -0.059 (-1.48) 0.168 (3.57) ** Control variables Age of program Organizational type Ln(employees) Training Internal control Intercept *** Adjusted R2 (%) 11.1 8.90 F-statistic 6.38 4.73 N 622 592 *** *** Control variables include the same ones as in Table 5. 39 Table 9 Comparison of effects of alternative organizational structures TripleHi TripleHi HiPerfMeas Rwds 10.97 (0.00) HiPerfMeas DecRights HiRwdsDec Rights HiPerfMeas HiRwds 2.98 (0.09) 5.12 (0.02) 17.32 (0.00) 18.64 (0.00) 7.83 (0.00) 38.84 (0.00) 2.35 (0.13) 0.88 (0.35) 0.16 (0.69) .96 (0.33) .76 (0.38) 3.11 (0.08) 0.33 (0.57) 4.40 (0.04) 6.23 (0.01) .65 (0.42) 13.76 (0.00) 1.96 (0.16) 3.58 (0.06) 0.02 (0.87) 8.02 (0.00) 0.45 (0.50) 2.06 (0.15) 0.32 (0.57) 3.73 (0.05) 2.28 (0.13) HiPerfMeasRwds 2.80 (0.09) HiPerfMeasDecRights 5.95 (0.01) .20 (0.65) HiRwdsDecRights 3.49 (0.06) 001 (0.90) .10 (0.74) HiPerfMeas 17.23 (0.00) 3.33 (0.07) 2.43 (0.12) 3.01 (0.08) HiRwds 11.13 (0.00) 2.31 (0.13) 1.48 (0.22) 1.97 (0.16) 0.05 (0.82) HiDecRights 9.29 (0.00) 0.60 (0.44) 0.13 (0.71) 0.44 (0.51) 1.57 (0.21) 0.76 (0.39) TripleLo 27.08 (0.00) 5.27 (0.02) 4.15 (0.04) 4.89 (0.02) 0.21 (0.64) 0.06 (0.80) HiDecRights TripleLo 10.09 (0.00) 3.04 (0.08) The upper triangle reports the F-statistic and significance of constraining the coefficients to be equal for capture of under $2,500 transactions on purchasing cards. The lower triangle reports the same statistic for the percentage of headcount reduction experienced in AP and Purchasing functions due to use of the purchasing card 40 Table 10 Relative performance under alternative organizational structures Covariate adjusted means Performance Variable % of Under $2,500 Transactions Paid by P- Card (t-statistic) % Reduction in AP/Purchasing Headcount (t-statistic) TripleHi 0.518(1) 0.217(1) DoubleHi 0.432 0.154 DoubleLo 0.429 0.144 TripleLo 0.360 0.130 TripleHi 0.518(2) 0.217(3) HiPerfMeasRwds 0.394 0.164 HiPerfMeasDecRights 0.454 0.141 HiRwdsDecRights 0.444 0.161 HiPerfMeas 0.393 0.124 HiRwds 0.395 0.152 HiDecRights 0.477 0.157 TripleLo 0.360 0.130 (1) Significantly different (1% or less) from DoubleHi, DoubleLo, TripleLo. (2) Significantly different (1% or less) from HiPerfMeasRwds HiPerfMeas, HiRwds, HiDecRights, TripleLo; significantly different (5% of less) from HwRwdsDecRights; significantly different (10% or less) from HiPerfMeasDecRights. (3) Significantly different (1% or less) from TripleLo, HiPerfMeas, HiRwds, HiDecRights; significantly different (5% of less) from HiPerfMeasDecRights; significantly different (10% or less) from HiPerfMeasRwds, HwRwdsDecRights. 41 Appendix A DEPENDENT VARIABLES CAPTURE OF LOW VALUE TRANSACTIONS ON PURCHASING CARD Please estimate the current percent of ALL transactions paid by payment mode based on transaction amount. Payment Mode Percent of All Transactions of $2,500 or Less, by Payment Mode Percent of All Transactions Over $2,500, But Less Than $10,000, by Payment Mode Plastic and traditional ghost p-card accounts __ __ __ % __ __ __ % “Electronic payables” p-card accounts __ __ __ % __ __ __ % Paper check __ __ __ % __ __ __ % Automated Clearing House (ACH) transfers __ __ __ % __ __ __ % Wire transfer __ __ __ % __ __ __ % Other (describe):_________ __ __ __ % __ __ __ % 100% 100% TOTAL (answers should sum to 100%) HEADCOUNT REDUCTION Please report answers to items (a) and (b) below on a “full time equivalent”(FTE) basis here, for example, two half-time workers equal one FTE worker or three half-time employees equals 1.5 FTE.) (a) The total current number of employees working in: (b) Accounts Payable __,__ __ __.___ FTE Purchasing __,__ __ __.___ FTE The approximate number of additional personnel in Accounts Payable and/or Purchasing that your organization would need to hire if it completely eliminated its p-card program Accounts Payable __,__ __ __.___ FTE Purchasing __,__ __ __.___ FTE 42 INDEPENDENT VARIABLES PERFORMANCE MEASUREMENT Does your organization use a measure or measures to evaluate purchasing card program performance (e.g., amount of spending on card)? Yes No REWARDS What impact will p-card program performance have on the Purchasing Card Administrator’s… No Impact Significant Impact pay and bonuses? promotions? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 obtaining of preferred future assignment(s)? 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 TRAINING Identify the basic training requirements for cardholders and supervisors who approve p-card spending. DOES YOUR ORGANIZATION: provide easy access to a copy of the policies and procedures manual for p-card use to every p-card cardholder? require initial purchase card training for cardholder? Require refresher training periodically for cardholder? provide “web-based” purchasing card training materials? provide “in-person” purchasing card training? provide “self-study” purchasing card training materials? track completion of training and training updates by employees? support p-card program administrator attendance at “p-card user conferences” to identify new ways to use p-cards? have an ongoing method of communicating p-card information (e.g., live or video information sessions, bulletin boards, newsletters) to cardholders and managers? have a Web site that answers p-card questions? Yes No Please rate support of the p-card program at your organization. AT MY ORGANIZATION…. a strong "business case" is made to employees about the benefits of p-cards. Do Not Agree 1 2 Fully Agree 3 4 5 6 43 7 INTERNAL CONTROL DOES YOUR ORGANIZATION: require cardholders to maintain a logbook of card activity? Yes No have a documented policy regarding receipt retention for p-card spending? Yes No officially reprimand or discipline cardholders who fail to submit receipts in a timely manner? Yes No evaluate the spending patterns of cardholders with a high number of disputed transactions Yes No de-activate p-card accounts that are unused for an extended period? Yes No track and resolve disputed transactions? Yes No formally audit and review the p-card spending approval process? Yes No conduct data mining of p-card transactions to identify potential policy violations or p-card misuse? Yes No OTHER (DECISION RIGHTS RELATED) Please identify the most common per transaction spending limit placed on plastic purchasing cards at your organization: $1-$500 $501-$1,000 $1,001-$2,500 $2,501-$5,000 $5,001-$10,000 More than $10,000 Please identify the most common monthly spending limit placed on purchasing cards at your organization: $1 to $1,000 $1,001 to $3,000 $3,001 to $5,000 $5,001 to $10,000 $10,001 to $20,000 $20,001 to $50,000 Greater than $50,000 Please rate support of the p-card program at your organization. AT MY ORGANIZATION…. there is a top management “sponsor” who gives strong vocal support to the p-card program. Do Not Fully Agree Agree 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 44 45