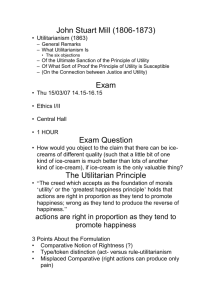

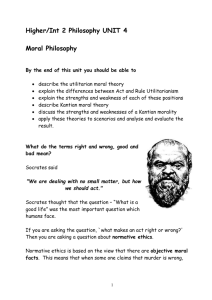

Notes on Utilitarianism

advertisement

Notes on Utilitarianism

1. Consequentialism refers to a variety of ethical theories that hold that rightness and

wrongness is not an inherent feature of actions – rather, it is a function of the

consequences of actions. Loosely, actions that have good consequences are right –

actions that have bad consequences are wrong. As a result, on consequentialist theories

we can’t tell what is right until we first decide what is good, because for the

consequentialist rightness (and wrongness) is a function of the goodness (and badness)

that actions cause. As Rawls puts it, for the consequentialist goodness is prior to

rightness.

2. Utilitarianism is a type of consequentialist view, differing from other consequentialist

views chiefly in how it defines goodness, or, in what amounts to the same thing, in how it

identifies which consequences matter. The consequences that are morally relevant to the

utilitarian are those that relate to happiness. Whose happiness? The happiness of any

and all beings affected by the action – for this reason Boatright describes utilitarianism as

universalistic.

3. But what is happiness, according to utilitarianism? The two great Classical

Utilitarians, Bentham and Mill, think happiness is solely a function of pleasure and the

absence of pain. That makes their view hedonistic. According to them, a happy life

would be one with great and many pleasures and few pains. They disagreed, though,

about the value of particular pleasures. For Bentham, all that matters is a pleasure’s

quantity (it’s intensity, duration, etc.) Take two pleasures, say, the pleasure of eating

potato chips and the pleasure of figuring out a subtle and difficult math problem. (Even

if you don’t generally like math, figuring out a problem can still be pleasurable!) For

Bentham, so long as these two pleasures are felt with equal intensity, last equally long

etc., they’re equally valuable. Hence his saying that other things being equal, "pushpin is

as good as poetry." ('Pushpin' is a children's game, analogous to tic-tac-toe.) But Mill

disagreed. He thought pleasures also differed in terms of quality – some are worth more

because of the kind of pleasures that they are. Solving a difficult math problem gives a

“higher” and more valuable pleasure than eating chips, even when the pleasures are

equally intense, last equally long, etc. Hence his saying that it’s better to be Socrates

dissatisfied than a pig satisfied – because the few “higher” pleasures that a dissatisfied

Socrates enjoys are much more valuable than the many “lower” the pig has. It’s an

interesting philosophical issue as to who’s right here about pleasure, but not something

we’ll need to be particularly worried about. Most contemporary philosophers and

economists who defend Utilitarianism abstract from this dispute about pleasures

altogether, and simply write about what satisfies preferences, regardless of the object of

people's preferences.

4. The Principle of Utility is this: An action is right if and only if it produces more

happiness (more pleasure and less pain) for all concerned than any alternative action. In

addition to being consequentialist, universalistic, and hedonistic, the principle of utility is

also a maximizing principle. This means that in order to know an action is right it’s not

enough just to know it produces much pleasure in many people – we have to also know

that it produces more pleasure and less pain overall than any alternative action would

have produced. Alternatively, to know an action is wrong, we need to know more than

the fact that it produces much pain in many people, since maybe any action in that

situation would have produced much pain. (Think of President Truman’s decision to

either drop the atomic bomb on Japan or let the war drag on – either way, many people

die.) We would need to know that an alternative action would have produced less pain

and/or more pleasure. Further, despite the slogan, “the greatest good for the greatest

number,” it doesn’t follow that an action is right just because it positively affects more

people than the alternatives. We also need to know how much it affects them – what

matters is not the number of people but the overall amount of pleasure and minimization

of pain produced.

5. Two complications: First, because a person thinks she is doing something that

maximizes happiness (and minimizes unhappiness), it doesn’t follow that the person does

the right thing. What matters is the reality, not someone’s perceptions or motivations. If

you’re trying to help, but still doing something sure to lead to disaster, it’s still wrong,

according to the Utilitarian. Second, there’s a debate among Utilitarians about whether

it’s the actual consequences or the reasonably expected consequences that count. On the

actual consequences view, an action could turn out to be wrong because it had some

disastrous but totally unexpected consequences that the agent couldn’t have foreseen, or

for that matter, right because of some wonderful and yet entirely accidental

consequences. This makes the theory less plausible, generally, and for this reason we’ll

stipulate that it’s the reasonably expected consequences that count. (Reasonably

expected consequences are still different from what the agent may actually expect.) But

how then do we take merely possible consequences into account? Multiply the possible

consequences by their likelihood. (Something with a 10% chance of producing 100 units

of pleasure, for example, goes on the scale as .1 x 100, that is, 10.)

6. So far, we’ve been talking about what’s called Act Utilitarianism, because we’ve been

speaking as though what makes the action right or wrong is the (reasonably expected)

consequences of that action, and no other. But there are good reasons for Utilitarians not

to be Act Utilitarians. For one thing, it seems quite possible for actions to be wrong and

yet still have maximally beneficial consequences, and vice versa. One way around this is

to shift to what’s known as Rule Utilitarianism. For Rule Utilitarians, particular actions

are right or wrong depending on their relationship to justified moral rules. Thus, if an

action is bribery, and there’s a justified rule that says, “Never bribe,” the action would be

wrong even if the consequences of this particular action were better than any alternative.

What makes the view Utilitarian is the idea that rules are justified if the general

observance of that rule has better overall consequences (with respect to happiness) than

any other rule. This view is still consequentialist, maximizing and universalistic, but only

indirectly so, since these are aspects of evaluating particular rules, not individual actions.

Another way to express the contrast with Act Utilitarianism is to say the Rule Utilitarian

is concerned not with particular actions, but with action types.