Weber`s Theory of Bureaucracy and Modern Society

advertisement

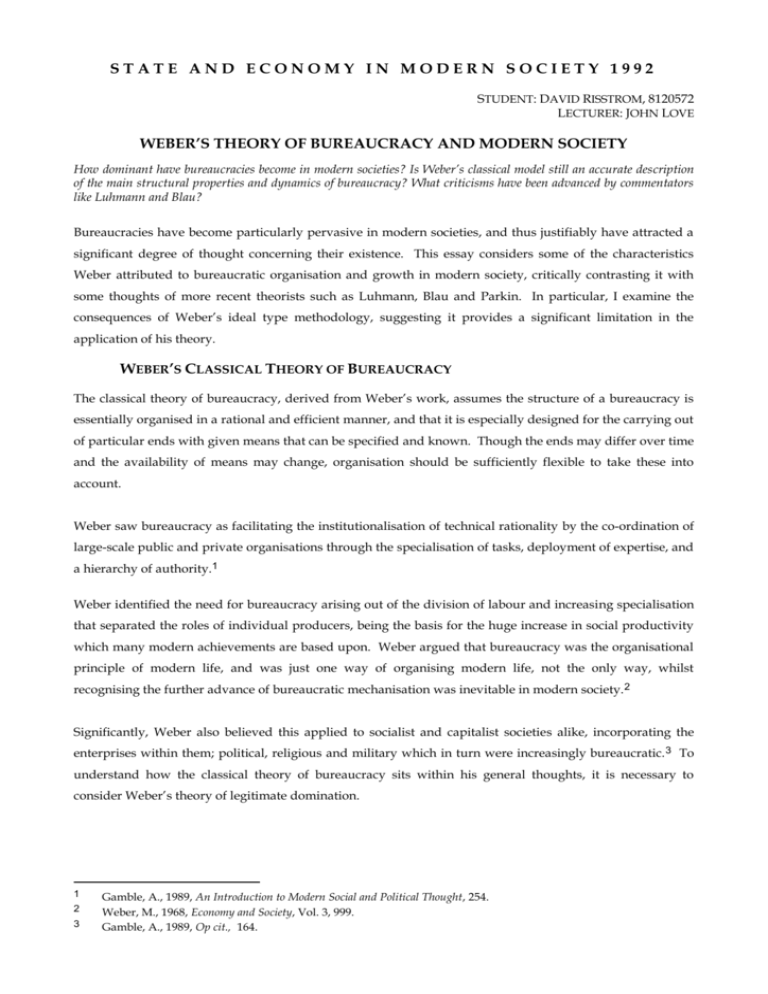

STATE AND ECONOMY IN MODERN SOCIETY 1992 STUDENT: DAVID RISSTROM, 8120572 LECTURER: JOHN LOVE WEBER’S THEORY OF BUREAUCRACY AND MODERN SOCIETY How dominant have bureaucracies become in modern societies? Is Weber’s classical model still an accurate description of the main structural properties and dynamics of bureaucracy? What criticisms have been advanced by commentators like Luhmann and Blau? Bureaucracies have become particularly pervasive in modern societies, and thus justifiably have attracted a significant degree of thought concerning their existence. This essay considers some of the characteristics Weber attributed to bureaucratic organisation and growth in modern society, critically contrasting it with some thoughts of more recent theorists such as Luhmann, Blau and Parkin. In particular, I examine the consequences of Weber’s ideal type methodology, suggesting it provides a significant limitation in the application of his theory. WEBER’S CLASSICAL THEORY OF BUREAUCRACY The classical theory of bureaucracy, derived from Weber’s work, assumes the structure of a bureaucracy is essentially organised in a rational and efficient manner, and that it is especially designed for the carrying out of particular ends with given means that can be specified and known. Though the ends may differ over time and the availability of means may change, organisation should be sufficiently flexible to take these into account. Weber saw bureaucracy as facilitating the institutionalisation of technical rationality by the co-ordination of large-scale public and private organisations through the specialisation of tasks, deployment of expertise, and a hierarchy of authority.1 Weber identified the need for bureaucracy arising out of the division of labour and increasing specialisation that separated the roles of individual producers, being the basis for the huge increase in social productivity which many modern achievements are based upon. Weber argued that bureaucracy was the organisational principle of modern life, and was just one way of organising modern life, not the only way, whilst recognising the further advance of bureaucratic mechanisation was inevitable in modern society. 2 Significantly, Weber also believed this applied to socialist and capitalist societies alike, incorporating the enterprises within them; political, religious and military which in turn were increasingly bureaucratic. 3 To understand how the classical theory of bureaucracy sits within his general thoughts, it is necessary to consider Weber’s theory of legitimate domination. 1 2 3 Gamble, A., 1989, An Introduction to Modern Social and Political Thought, 254. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 3, 999. Gamble, A., 1989, Op cit., 164. The phenomena of specialisation of occupational function is central to Weber’s sociology of modern capitalism, being by no means limited to the economic sphere.1 Separation of the labourer from control of her means of production, seized by Marx as the most distinctive feature of modern capitalism is not seen by Weber as being confined to industry, rather extending throughout the polity, army and other sectors of society having prominent large scale organisations.2 LEGITIMATE DOMINATION: THE FOUNDATION OF BUREAUCRACY Weber formed a distinction between traditional, charismatic and legal-rational types of legitimate domination to explain why people believe they are obliged to obey the law. Traditional legal domination is where legitimacy is claimed on the basis of belief in the sanctity of age-old rules and powers. Charismatic legal domination is based on ‘devotion to the exceptional sanctity, heroism or exemplary character of an individual person’, whilst legal-rational domination is founded on a belief in the legality of enacted rules and the right of those elevated to authority under such rules to issue commands. Within the legal rational type, which best describes modern society, the commonest form of its expression is found in bureaucracy. Though the notion of legal-rational authority is bound up with Weber’s theory of value, which argues that the sociologist must adopt a detached view of his subject, the important correlation is between this form of domination and the modern bureaucratic State. Weber points out that under other forms of domination, authority resides with people, whilst under bureaucracy it is vested in rules. Weber saw the hallmark of legal-rational authority as its so-called impartiality3, though this depends on what Weber calls the principle of ‘formalistic impersonality’ which requires that officials discharge their responsibilities ‘without hatred or passion’, and hence without affection or enthusiasm. The dominant norms are thus concepts of straightforward duty without regard to personal considerations. 4 Weber argues that whilst the legitimacy of the traditional and charismatic forms of legal domination depends on specific relationships between ruler and subject, the source of legitimacy of legal-rational domination is impersonal. Obedience therefore becomes owed to the legal order, rather than to an individual or social group. This might be set out as follows5; DOMINATION LEGITIMATION LEGAL THOUGHT JUSTICE JUDICIAL PROCESS OBEDIENCE ADMINISTRATION 1 2 3 4 5 Traditional Traditional Formal irrationality Substantive irrationality Secular or theocratic empirical Empirical and/or substantive and/or personal (Khadi justice) Charismatic Charismatic Formal irrationality Substantive irrationality Charismatic Legal-rational Legal-rational Logical formal rationality Rational Rational Owed to legal order Bureaucratic professional Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 158. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 158. Wacks, 1990, Jurisprudence, 146. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, 225. Wacks, 1990, Op cit., 148. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 2 Weber makes a variety of claims in support of his theory of legitimate domination. Weber’s political domination draws its legitimacy from the existence of a system of rationally made laws that stipulate the circumstances under which power may be exercised. Weber sees this form of legitimacy as the central core of all stable modern societies, with legal rational rules determining the scope of its power and providing its legitimacy. FEATURES OF WEBER’S IDEAL TYPE BUREAUCRACY For Weber, an organisation with a bureaucratic nature is an extension of the will of the commanding power, with the legitimacy of the system resting ultimately upon the extent to which it is accepted. Weber’s notion of bureaucracy, perhaps the most influential of his theories, is prefaced upon his ideal type. 1 As I will discuss later, Weber’s tendency to abstract and accentuate selected interrelated aspects of a social phenomenon, rather than aiming at a full description of it, has brought criticism to his theory, and has limited its usefulness in describing more modern large scale bureaucratic phenomena. 2 In elucidating his classical model of bureaucracy, Weber identified six specific criteria. These are, firstly, that the spheres of competence of the officials are clearly demarcated. This means that the regular activities required for the purposes of the bureaucratically governed structure are distributed in a fixed manner as official duties, which incorporates the authority to give commands is distributed in a stable way and is strictly delimited by rules concerning the coercive means, physical, sacerdotal, or otherwise that may be placed at the disposal of officials and that administrative activities are carried out on a regular basis, constituting well defined ‘official duties’.3 Weber explains this by saying, “There is a principle of fixed and official jurisdictional areas which are generally ordered by rules, that is by laws or administrative regulations.”4 Secondly, he notes that officials gain their positions through appointment, saying, “The principles of office hierarchy and of levels of graded authority mean a firmly ordered system if super- and subordination in which there is a supervision of the lower offices by the higher ones.” 5 Thirdly that, “The management of the modern office is based upon written documents (the files) which are preserved in their original or draught form.”6; Fourthly, that “office management, at least all specialised office management and such management is distinctly modern - usually presupposes thorough and expert training.”7; Fifthly that, “When the office is fully developed, official activity demands the full working capacity of the official, irrespective of the fact that his obligatory time in the bureau may be firmly 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, 34. Wrong, D., Max Weber, 133. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 158. Weber, M., ‘Bureaucracy and Law’ in Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, 196. Weber, M., 1991, Op cit., 197. Ibid. Id., 198. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 3 delimited”1, and finally that, “The management of the office follows general rules, which are more or less stable, more or less exhaustive, and which can be learned.”2 Expanding upon the role of officials, Weber suggests they are recruited and promoted mainly on merit, being unable to formally trade their position. Rather than being independent property owners in their capacity as officials, people regard their work as a career in which they can expect to progress. As a consequence, they tend to develop an ethic of service, duty and altruism, rather than being motivated primarily by financial gain or self interest, thus sharing the orientation to work the capitalist entrepreneur which Weber had admired.3 Weber writes, “The actual social position of the official is normally highest where, as in old civilised countries, their is a strong demand for administration by trained experts, and a strong and stable social differentiation or where the costliness of the required training and status conventions are binding upon him.”4 Weber acknowledges that some institutions are only semi-bureaucratic, being aware that the ideal type won’t always be available in pure form. Giddens believes it is only within modern capitalism that organisations approximating Weber’s ideal type are found, the notable examples of ancient Egypt, China, the Roman principate and the medieval Catholic church being exceptions.5 SOME THOUGHTS ON WEBER’S SCHEMA OF LEGAL-RATIONAL DOMINATION Weber says, “In a modern state the actual ruler is necessarily and unavoidably the bureaucracy…” 6 The bureaucracy distinguishes itself from the other forms of domination described by Weber, in that authority is vested in rules, not individuals. Weber believes that the Middle Ages tradition of office holding being a source of exploitation has changed, and in compensation for the nature of their employment, he says, “Legally and actually, office holding is not considered a source to be exploited for rents or emoluments, as was normally the case during the Middle Ages and frequently up to the threshold of recent times.”7 Entrance into an office, including one in the private economy, is considered an acceptance of a specific obligation of faithful management in return for a secure existence. It is decisive for the specific nature of modern loyalty to an office that, in the pure type, it does not establish a relationship to a person. … Modern loyalty is devoted to impersonal and functional purposes.8 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ibid. Ibid. Gamble, A., 1989, An Introduction to Modern Social and Political Thought, 154. Weber, M., ‘Bureaucracy and Law’ in Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, 200. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 158. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 3, 1133. Weber, M., 1991, Op cit., 199. Ibid. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 4 Weber had argued that bureaucracy afforded advantages in the way it could procure a monopoly over the means of information, being the “Supreme power instrument [in] the transformation of official information into classified material1, but is nevertheless is critical of the exercise of this ability, citing the then activities of the German civil service, claiming intrusion of the bureaucracy into the political spheres as an abuse of power.2 This however, unwittingly for Weber, appears to present a dichotomy in his theory of legitimate domination, as Weber’s conception of legal domination exhibits an unduly positivist view of law, as evidenced by Cotterrell’s claim that “… the highly complex ideological elements of law must be analysed in ways that cannot utilise the ideal type method, if conditions of legitimacy are to be understood in relation to social change”.3 Parkin considers why bureaucracy should qualify as a form of domination saying, “If bureaucracy does attempt to exercise domination it usurps the authority of a nominally superior body, or in other words it uses its power illegitimately. Thus, in the light of Weber’s own account, bureaucracy can hardly be an example of ‘legitimate domination’, for if the bureaucracy does attempt to exercise domination, it usurps the authority of its superior body, and thus uses its power illegitimately. This, for Parkin, means that under Weber’s theory of legitimate domination, if a bureaucracy acts legitimately it is not dominant, whilst if it exercises domination is ceases to be legitimate.4 Giddens believes Weber’s position has been misunderstood, claiming Weber was not unaware of the importance in the substantive operation of bureaucratic organisations or the existence of informal contacts and patterns of relationship overlapping the formal designation of authority and responsibilities. 5 Giddens says that according to Weber, prior forms of administrative organisations may be superior in dealing with a particular case, which can be illustrated in the instance of just judicial decisions. 6 The importance Weber attached to the existence of the bureaucracy can be seen in his statement that, “It would be an illusion to think for a moment that continuous administrative work can be carried out in any field except by means of officials working in offices. The whole pattern of every day life is cut to fit this framework. If bureaucratic administration is, ceteris paribus, always the most rational type from a formal, technical point of view, the needs of mass administration make it today completely indispensable. 7 LUHMANN, BLAU’S AND PARKIN’S CRITICISMS OF WEBER’S THEORY OF BUREAUCRACY Weber selects and emphasises the features of bureaucracy as discussed above; a formal hierarchy, consistent application of rules, promotion by merit or seniority, strict control of files and information, etc., as being its distinctive hallmark.8 Weber says, 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Weber, M., 1968, Op cit., 1134. Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, 88. Cotterrell, cited in Sugarman, D., (ed.), 1983, Legality, Ideology and the State, 88. Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, 89. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 159. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 2, 656. Giddens, A, 1981, Op cit., 160. Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, 34. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 5 “the fully developed bureaucratic apparatus compares with other organisations exactly as does the machine with the nonmechanical modes of production. Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs - these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic administration.” 1 Blau and Meyer are critical of interpretations of Weber’s use of the ‘ideal type saying, “This methodological concept does not represent an average of the attributes of all existing bureaucracies (or other social structures), but a pure type, derived by abstracting the most characteristic bureaucratic aspects of all known organisations. Since perfect bureaucratisation is never fully realised, no empirical organisation corresponds exactly to this scientific construct.” … The criticism has been made that Weber’s analysis of an imaginary type does not provide understanding of concrete bureaucratic structures. But this criticism obscures the fact that the ideal-type construct is intended as a guide in empirical research, not as a substitute of it.” 2 Luhmann, in The Differentiation of Society, criticised Weber’s consideration of the operations of bureaucracies as too simplistic, claiming Weber’s classical theory of bureaucracy assumes most organisations orient their activities according to ends in a Western overtly rationalistic way, based on a command version of how organisations work. Luhmann also questions the supposition that all ends are instructive. They are often a vague and ambitious justification of themselves, and don’t necessarily bind it to any specific ends. Means and ends schema are often irrelevant as such, in that the goals are sometimes not able to be expressed at all, and may change with variation in the culture. As the ends do not specify the means unambiguously, the sub goals of the organisation are regularly in conflict with one another, so that a structure with contrary goals may exist from the very start, such as can occur in some welfare organisations. Luhmann also recognises that for an organisation to function well, it doesn’t necessarily require the complete loyalty and obedience of its employees, as a partial consensus would likely suffice. Blau, also providing some criticism of Weber’s theory of bureaucracy for its construction upon the ideal type, claiming its crude nature fails to differentiate between conceptual elaborations and hypotheses concerning the relationship between analytical attributes of social systems and prototypes of the social systems themselves.3 Blau suggests that Weber considers the three analytical principles of convention, ethics and law underlie conformity, whilst at other times seemingly referring to political systems; traditional political institutions, revolutionary movements, and modern governments based on rational law, suggesting that the limitations of the ideal type may be responsible for such discrepancies. 4 Blau is also critical that Weber subsumes democracy under the legal order in his model of legal-rational behaviour discussed previously, particularly as Weber makes it clear that bureaucracies are not necessarily democratic. Critical that Weber never systematically differentiates the two concepts in the way he had done 1 2 3 4 Weber, M.,1968, Op cit., 973. Blau, P., and Meyer, M., 1956, Bureaucracy in Modern Society, 24. Blau., P., 1970, ‘Critical Remarks on Weber’s Theory of Authority’ in Wrong, D., Max Weber, 164. Id., 160. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 6 so with the other two types of authority structures, Bendix says, “power in the political struggle results from the manipulation of interests and profitable exchanges … and does not entail legitimate authority of protagonists over one another. Success, however, in this struggle leads to a position of legitimate authority.1 Blau notes that, “If men organise themselves and others for the purpose of realising specific objectives assigned to or accepted by them … they establish a bureaucratic organisation. The exact form best suited for such an organisation depends on a variety of conditions, including the kinds of skills required for the tasks.”2 Blau notes that as the differentiating criteria between democracy and bureaucracy proposed are whether the organisation’s purpose is to settle on common objective … and whether the governing principle of organising social action is majority rule rooted in freedom or dissent or administrative efficiency”, the two principles come into conflict.3 Blau consider the example of unions as a case in point to highlight the deficiencies in Weber’s theory. As for Blau, Parkin is critical of Weber, claiming that he has failed to measure these claims against the existing bureaucracies, pointing to the fact that Weber appears not to present any evidence to indicate that organisations that depart from the ideal type actually do suffer from a loss of precision, speed or ambiguity. 4 Parkin also notes that Weber’s classical model of bureaucracy is one of highly formalised and inflexible rules, as outlined in Weber’s claim that, “Bureaucracy develops the more perfectly it is ‘dehumanised’, the more completely it succeeds in eliminating from official business love, hatred, and all purely personal, irrational and emotional elements which escape calculation.”5 The issue then arises as to what happens to the notion of taking the individual’s subjective meanings as the starting point of social enquiry; the Verstehen approach6, if bureaucracy is viewed in this way.7 This appears to be a significant flaw in Weber’s theory. Parkin believes that once the personal motivations and perceptions of individual incumbents are considered, a clearer picture of why bureaucracies do not parallel the ideal type is uncovered. 8 The jump Weber appears to make using his notions of bureaucracy based on the ideal type of bureaucracy, does not adequately address the problem that many bureaucrats do not behave in the way Weber deems them to. The tendency for officials to accrue power to their own ends can mean the impartiality of the bureaucracy becomes a force fiction. What would now be seen as the naivety of Weber’s outlook is shown in Weber’s assertion that whilst it is proper for a bureaucrat to present a reasoned case in advising his minister, he is duty bound to accept the minister’s decision and to implement it as conscientiously as though it corresponds to his own innermost conviction.9 Based on this concern, it is possible that if Weber had 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bendix, R., Max Weber, 439. Blau., P., 1970, Op Cit., D., Max Weber, 163. Blau., P., 1970, ‘Critical Remarks on Weber’s Theory of Authority’ in Wrong, D., Max Weber, 163. Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, 34. Weber, M.,1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 3, 975. Parkin, F., 1982, Op cit., 15. Id., 35. Id., 36. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, 1417, cited in Parkin, F., Op cit., 88. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 7 referenced his theory of bureaucracy with his Verstehen approach, the criticisms of people in the Human Relations movement such as Mayo would be less evident. LIMITS OF THE WEBERIAN MODEL. Weber’s framework for bureaucracy was that of an undemocratic system that did not allow for election of fellow employees. Nevertheless, bureaucracies are inherently efficient organisations, which is why they are so central to modern organisations. As no alternatives to bureaucracies appeared evident for the efficient running of large scale organisations, Weber was fearful of legal-rational thought developing into an all encompassing ossified ‘iron cage’ of bureaucracy that thwarted the very values of freedom and liberty he desired.1 The English bureaucracy was a case in point for Weber. So whilst Weber wants to celebrate the Western Culture heritage that has allowed such amazing progress, though in its last stages, we have created a new form of bureaucratic organisation which is much more rational, coherent and stable than anything before, the question remains as to how we can retain a social structure allowing mobility, with the tendency for bureaucracy Weber says there is another trend at work called rationalisation, ‘the rationalisation and intellectualisation of the world is receding regardless of what we would like. We have institutionalised economic progress and scientific development to the extent that our culture has become totally dependent on making these advances in one form or another. Weber believes the formal rationality of bureaucracy whilst facilitating the technical implementation of large-scale administrative tasks, substantially contravenes some of the most distinctive values of Western civilisation, in subordinating individuality and spontaneity. The question arises as to whether Weber says we should acquiesce to these principles, or rather, of whether the bureaucratic form is the most rational becomes the issue. Nevertheless, Weber sees no rational way to escape this, it being “the fate of the times”. 2 Pusey captures this well, saying, “In Weber’s often quoted view, “experience tends universally to show” that order of this type is: “from a purely technical point of view, capable of attaining the highest degree of efficiency and in this sense formally the most rational means of carrying out imperative from control over human beings. Is it superior to any other form in precision, in stability in the stringency of its discipline, and in its reliability.”3 Weber’s model has an inability to properly account for the informal structure within organisations; it is over rationalistic, has a tendency to persist in a firm inconsistent with the ideal structure of the bureaucracy. This issue remains an open question for me, and may be best outlined by Mikel Duffrenne’s words at the opening of the International symposium on ‘Rationality Today’. 1 2 3 Gamble, A., 1989, An Introduction to Modern Social and Political Thought, 163. Weber, M., 1968, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 182. Pusey, M., 1984/5, Citing Weber, M, ‘The Theory of Social and Economic Organisation’ in Rationality, Organisations, and Language Towards a Critical Theory of Bureaucracy’ in Thesis Eleven, No. 11, 89. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 8 The task of reason is not easy: to say No to the System is intellectually easy even if, on occasions, it takes some heroism. But how was we to say simultaneously both Yes and No? How does one invent a strategy without making a game of strategies? How are we to reconcile spontaneity and organisation? How can we want efficiency and renounce technocracy? And, further, how do we steer a course between a rationalism which identifies rationality with rationalisation and an irrationalism which leaves us without resources?1 Whilst Luhmann talks about the rise of horizontal connections within bureaucracies as an important connection here, therefore making it possible that the rationalisation of society will maintain a potential flexibility that will avoid the ‘iron cage’ effect, therefore not necessarily heading to total democracy but organisational life needed cover the entire social life, the discomfort that encroaching bureaucracy may bring to the liberal will probably still remain. HOW PREVALENT ARE MODERN BUREAUCRACIES ? The modern capitalist state is completely dependant upon bureaucratic organisation for its continued existence. As Weber says, “The larger the state, or the more it becomes a great power state, the more unconditionally this is the case.”2 Nevertheless, whilst the size of the administrative unit is a major factor determining the spread of rational bureaucratic organisation, there is not a unilateral relationship between size and bureaucratisation.3 The necessity of specialisation to fulfil specific administrative tasks is as important as size in promoting bureaucratic specialisation.4 As Weber identified, the major reason for the encroachment of bureaucratic organisation into the performance of routinised tasks is its efficiency.5 “The fully developed bureaucratic apparatus compares with other organisations exactly as does the machine with the non-mechanical modes of production. Precision, speed, unambiguity, knowledge of the files, continuity, discretion, unity, strict subordination, reduction of friction and of material and personal costs - these are raised to the optimum point in the strictly bureaucratic organisation…” 6 Weber believes the growth of the bureaucratic state is allied with the advance of political demarcation, as the demands made by democrats for political representation and equality before the law necessitate complex administrative and juridical provisions to lawfully limit privilege.7 It is this very relationship between democracy and bureaucratisation that Weber believes creates one of the most profound sources of tension in modern capitalism. This contradiction between the formal and substantive rationality of social actions is illustrated by development of abstract legal procedures which, in helping to eliminate privilege, reintroduce 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ibid. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 3, 971. Ibid., 1003. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 159. Ibid., 159. Weber, M., 1968, Op cit., 973. Giddens, A, 1981, Op cit., 180. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 9 a new form of entrenched monopoly which is in some respects more arbitrary and autonomous than that which they influence.1 Thus, bureaucratic organisation is promoted by the democratic requirement for impersonal selection of office bearers according to the possession of educational qualifications, but this in itself creates a stratification as identified by Luhmann, that produces a privileged group having more administrative power than before. Giddens recognises that government solely by the masses is an impossible aim in large modern societies, with direct democracy only being possible in small scale communities. As Weber says in Politics as a Vocation, “… there is only one choice between leadership democracy with a ‘machine’ and leaderless democracy, namely, the rule of professional politicians without a calling, without the inner charismatic qualities that make a leader, and this means what the party insurgents in the situation usually designate as ‘the rule of the clique’.2 Bureaucracy is a consequence of not merely in the sphere of politics or government, but society in general. In some respects, Weber’s focus on bureaucracy is his answer to the idealism of Marxism. Marxism saw prospects for increasing freedom coming out of the most advanced social forms arising from capitalism, whilst Weber saw great changes and threats in its allied reliance on bureaucracy. Weber was worried by the naivety of Marx’s view in “expropriating the expropriators”, regarding this as simply replacing a multiplicity of capitalists with a simple unified capitalist. Giddens, thus identifies the most significant divergence between Marx and Weber as being how far the alienating consequences of the rationalisation of society derive from bureaucratisation, which is a necessary requisite of the modern society, whether capitalist or socialist.3 Thus, whereas Marx saw socialism as the panacea of the evils of capitalism, Weber saw socialism would necessitate “a tremendous increase in the importance of professional bureaucrats”4, thus exacerbating the worst evils of capitalist bureaucracy and therefore alienation. Weber believes that once bureaucracy has become established it is extremely resistant to any attempt to remove its powers. He says, “Such an apparatus makes ‘revolution’, in the sense of the forceful creation of entirely new formations of authority, more and more impossible…”5 The encroachment of bureaucracy across modern capitalism is thus both cause and consequence of the rationalisation of law, politics and industry, being the concrete, administrative manifestation of the rationalisation of action which has penetrated into all spheres of Western culture.6 Giddens believes this spread of rationalisation can be indexed by the progressive ‘disenchantment of the world’; the elimination of magical thought and practice, induced by the great religious prophets and the systematising activities of priests. 7 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Ibid., 180. Weber, M., ‘Bureaucracy and Law’ in Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, 113. Giddens, A, 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory: An Analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Max Weber, 216. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, Vol. 1, 224. Weber, M., 1968, Op cit., 989. Giddens, A, 1981, Op cit., 183. Ibid. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 10 Weber notes the connection of bureaucracy with the work ethic, as he explored in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism1, but makes the important distinction that whilst the “Puritan wanted to work in a calling; we are forced to do so.”2 Weber believed people’s relation to work was not as mere labour, but as invariably adopted as a form of vocation evidenced by the need for training qualifications. Weber noted that the official takes on his/her work with a sense of carrying out a task according to a sort of spirit or ethic with moral overtones. The main normative issue then is not how the process of bureaucratisation can be reversed, but, “What can we set against this mechanisation to preserve a certain section of humanity form fragmentation of the soul, this complete ascendancy of the bureaucratic ideal of life” 3 Bureaucracy has had the effect of institutionalising expertise. The more bureaucratised a country, the more attention was paid to expert knowledge and efficiency. Welfare and progress became increasingly determined using terms defined by experts. The culture becomes rationalist and utilitarian, searching out the cheapest and effective manner for achieving stated goals, with social goals tending to become defined in terms of the technical means that are available, with democracy becoming irksome as it is increasingly perceived that only experts have the knowledge and experience to decide. 4 Taken to their ultimate limit, these ideas imply that industrial society is best run without a democratic political system that may only hamper the interests of professional bureaucracies of government, and the private sector. The realities of government meant it was impractical to implement the untested initiatives that may evolve from a democratic political process, with modern bureaucracies having evolved to compromise discrete and specialised sphere headed and jealously guarded by their own expert bureaucracies.5 Given these observed pitfalls, why is it that bureaucracies have not diminished? WHY HAVE BUREAUCRACIES BECOME SO PREVALENT? Initially, the reasons for bureaucracy were primarily military. Superiority of the standing army over knightly warfare meant the first European modern bureaucracies were needed to be funded reliably. Weber refers to the development of these bureaucracies saying, Among purely political factors, the increasing demand for a society accustomed to absolute pacification, for order or protection in all fields exerts an especially persevering influence in the direction of bureaucratisation. A steady road leads from modifications of the blood feud, sacerdotally, or by means of arbitration, to the resent position of the policeman as the ‘representative of God on earth’. The former means placed the guarantees for the individual’s rights and security squarely upon the members of his sib, who are obliged to assist him with oath and vengeance. Among other factors, primarily the manifold tasks of the so-called ‘policy of social welfare’ operate in the direction of bureaucratisation, for these tasks are, in part, saddled upon the state by interest 1 2 3 4 5 Weber, M., 1968, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, 40. Weber, M., 1968, Op cit., 181. Giddens, A, 1981, Op cit., 236. Gamble, A., 1989, An Introduction to Modern Social and Political Thought, 165. Gamble, A., 1989, Op cit., 167. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 11 groups and in part, the state usurps them, either for reasons of power policy or for ideological motives.”1 Weber points to the connection of some of these things with purely technical aspects of modern society. For Weber, the modern means of communication enter the picture as ‘pacemakers’ of modern bureaucracy, ie; public lands, modern communication, railways, etc., become analogous to canals and rivers in ancient civilisations. In contrast, for Marx, the bureaucracy was ‘a parasitic growth on the back of society’, a useless collection of unproductive workers, who in contrast to the proletariat, make no real contribution to the productive output of society. A large number of studies have been done which help to critique Weber’s theory. One particularly well known critique is that of Elton Mayo of the Harvard Business School. Mayo was interested in how to produce a healthy work environment with morale and incentive rather than simply high wages or salaries. These studies were prompted by some 1930’s work which had found that people not only carry out orders, but also at times resist and obstruct the organisations aims. The recognition of informal structures has had important implications for organisation theory. The most important initial response was the theory of Human Relations as developed by Mayo, which sought to reconcile the formal organisation with the informal structure, by placing a premium on the needs of the workers. Without undermining the command structure of the formal organisation, it argued it was possible to improve the level of job satisfaction by attending to the felt needs of the employees by job enrichment, extensive awards such as promotion and esteem, as well as salary. Mayo says an alternative arrangement may come into effect so that inverted power relations may occur, or people are circumvented. Also there might be solidarity to avoid particular commands and particular work levels to maintain. Problems exist because often the overseer is part of the system, as he wants consensus with the workers, so sometimes people you least expect to have power, have extreme power. This movement sought to encourage a more meaningful participation in decision making by making democratisation a goal of the bureaucratic structure. This was in contrast to Weber’s view that the bureaucratic structure is undemocratic, with people being elected on the grounds of competence rather then popularity or support from the employees, as the assumption that competence can only be recognised by those of greater competence. The effect of Human Relations has only been partly successful. In more recent times, ‘organisation culture’, or ‘culture theory’ has emerged, which gives emphasis to looking at various sometimes intangible features of a work environment which will improve things, by changes such as office refurbishing etc. The logic of the theory is that by altering the physical aspects of the work environment, the cultural ambience of the environment may improve. Certain types of work were more amenable to culture theory, such as the high technology industries, by the same notions may not work with very routine and mechanical processes are involved. Also, there was always an underlying assumption that it was possible to reconcile the formal and 1 Weber, M., ‘Bureaucracy and Law’ in Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, 213. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 12 informal structure into harmony, based an the assumption that you can subsume the informal structure into the formal structure. IN CONCLUSION: BUREAUCRACY AND DEBUREAUCRACY The attempt to debureaucratise is occurring to some extent, by the initiative of the bureaucratic organisations themselves. It has been found that in some circumstances, a less bureaucratic structure is efficient, though Weber had made an implicit assumption that there will be a more or less one to one correspondence between official sphere of competence and one’s actual functional competence. This is why Weber believed bureaucracies would always be inherently efficient. Bureaucratic inefficiencies nevertheless have obviously come about, as was evident in the old Soviet Bureaucracy. As the people at the top of organisations are by no means necessarily at the peak of power in organisations, Weber made a distinction between official and professional of functional power and authority, which is recognised om professional associations. Therefore, we have to acknowledge that a bureaucratic organisation is not the only way of rationalising institutions in the modern context. Probably more significantly, in considering the disparity between Weber’s classical theory of bureaucracy and practice, is his over reliance on the methodology of the ideal type, which as we have shown, has definite shortcomings, and deserves much of the critique detailed to it. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 13 BIBLIOGRAPHY Barry, N., 1989, An Introduction to Modern Political Theory, 2nd Edn., London: Macmillan. Beethem, D., 1974, Max Weber and the Theory of Politics, London: Allen and Unwin. Bell, D., 1976, The Cultural Contradictions of Capitalism, London: Heinemann. Bendix, R., 1962, Max Weber, Garden City: Doubleday. Berle, A., and Means, G., 1939, The Modern Corporation and Private Property, New York: Macmillan. Blau, P., 1970, ‘Critical Remarks on Weber’s Theory of Authority’ in Wrong, D., Max Weber, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Blau, P., and Meyer, M., 1971, Bureaucracy in Modern Society, 2nd. edn., New York: Random House. Blau, P., and Schoenherr, R., 1971, The Structure of Organisations, New York: Basic Books. Bittman, M., 1986, ‘A Bourgeois Marx? Max Weber’s Theory of Capitalist Society: Reflections on utility, rationality, and class formation’ in Thesis Eleven, No. 15, Melbourne: Philip Institute of Technology. Castoriadis, C., 1984/85, ‘Reflections on Rationality and Development’ in Thesis Eleven, No. 10/11, Melbourne: Philip Institute. Cotterrell, R., 1989, The Politics of Jurisprudence: A Critical Introduction to Legal Philosophy, London: Butterworths. Crozier, M., 1980, Actors and Systems: The Politics of Collective Action, London: University of Chicago Press. Crozier, M., 1964, The Bureaucratic Phenomenon, Chicago: University of Chicago. Delbridge, A. et al. (eds), 1981, The Macquarie Dictionary, New South Wales: Macquarie University. Emy, H. and Hughes, O., 1988, Australian Politics: Realities in Conflict, Sth. Melbourne, Macmillan. Friedman, M.,1962, Capitalism and Freedom, Chicago: University of Chicago Press. Gamble, A., 1987, An Introduction To Modern Social And Political Thought, Hampshire: Macmillan. Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, London: Routledge. Giddens, A., 1981, Capitalism and Modern Social Theory; An analysis of the Writings of Marx, Durkheim and Weber, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. Gough, I., 1979, The Political Economy of the Welfare State, London: MacMillan,. Habermas, J., 1970, Toward a Rational Society, London: Heinemann. Habermas, J., 1976, Legitimation Crisis, translated by McCarthy, T., London: Heinemann. Held, D., 1983, Models of Democracy, London: Oxford Univ. Press. Howard, D., 1989, Defining the Political, Hampshire: Macmillan Press. Hunt, J., 1972, Socialisation in Australia, Sydney: Angus and Robertson. Hutton, R., 1992, Economy and Society, New York: Routledge. Kamenka, E., (ed.), 1980, Ideas and Ideologies-Law and Social Control, London: Edward Arnold Publishers. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 14 Luhmann, N., 1982, The Differentiation of Society, New York: Columbia University Press. Marcuse, H., 1975, One-Dimensional Man, Boston: Beacon Press. Marcuse, H., 1964, Studies in Critical Philosophy, Trans. by Joris de Bres, London: NLB. Mayo, E., 1949, The Social Problems of an Industrial Civilisation, London: Routledge and Kegan Paul. McNall, S., 1979, Theoretical Perspectives in Sociology, New York: St. Martin’s Press. Offe, C., 1985, Disorganised Capitalism: Contemporary Transformations of Work and Politics, Cambridge: Polity Press. Parkin, F., 1982, Max Weber, London: Tavistock. Schumpeter, J., 1987, Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy, London: Allen and Unwin. Smith, R., and Watson, L., 1990, Politics in Australia, Wellington: Allen and Unwin. Wacks, R., 1990, Jurisprudence, London: Blackstone Press. Weber, M., ‘Bureaucracy and Law’ in Gerth, H., and Wright Mills, C., 1991, From Max Weber: Essays in Sociology, London: Routledge. Weber, M., 1968, Economy and Society, New York: Bedminster Press. Weber, M., 1968, The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism, Translated by Parsons, T., London: University Books. Wrong, D., 1970, Max Weber, New Jersey: Prentice-Hall. Bureaucracy / David Risstrom / Page 15